Please Be Nice to Me: Navigating History, Mystery, and Desire in Chris Kraus’s “After Kathy Acker”

In the first authorized biography of Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus digs beneath the myths around the avant-garde heroine.

By Anna IoanesSeptember 11, 2017

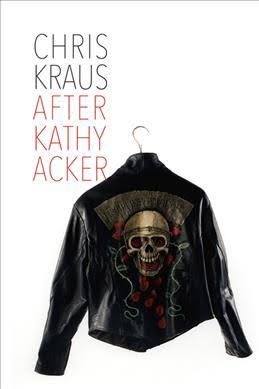

After Kathy Acker by Chris Kraus. Semiotext(e). 352 pages.

IN AN INTERVIEW with Sylvère Lotringer given some time around 1991, Kathy Acker situated a new development in her writing in terms of post-Watergate politics. In a world where people are aware of pervasive corruption and violence, even if they don’t “want to see it” or even “give a damn,” Acker argued that it is less urgent to unveil hypocrisy than it is to “start constructing” something new. “I became very interested in myths,” Acker said, adding that she wanted to write the kind of fiction that would “make a kind of myth that would be applicable to me and my friends.” The myths she constructed in her experimental fiction grew alongside the myths she constructed about herself: a punk-feminist badass, riding in on her motorcycle, a deconstructed Vivienne Westwood top showing off tattoos and ripped biceps. Her 1982 novel Great Expectations, a sexually explicit, violent, sometimes hilarious pastiche drawn from the text of Dickens and other writers as well as excerpts from her own diaries, launched Acker into the position of leading female avant-garde writer of the period. She spent the remaining 14 years of her life moving between London, New York, San Diego, and San Francisco, collecting a proliferating cache of lovers, before her death in 1997 at an alternative medicine hospital in Tijuana. She cultivated a persona that was by turns tough and vulnerable, a mythic example of the Great Writer as Cultural Hero, as Chris Kraus puts it in her new biography, After Kathy Acker. In this first authorized biography of Acker, Kraus refracts these myths through the prism of a deep archive of letters, diaries, published work, and interviews with those who knew her to offer a loving portrait of an artist that is also a tremendous pleasure to read.

The book begins at Acker’s funeral, a surreal and stylish scene populated by critical theorists, underground artists, and crystal healers. Beginning at the end might seem like a cheap postmodern trick, but instead, this structure orients readers with an endpoint and asks the question: how did we get here? By opening in a moment immediately “after” Kathy Acker, in the midst of her mourners, Kraus begins to map out the extensive and shifting network of Acker’s mentors, friends, lovers, and rivals. Kraus treats Acker’s death, the culmination of her refusal to undertake mainstream medical treatment for cancer, as an avoidable tragedy without rolling her eyes at Acker’s astrologers, antioxidant diet, or lingering desire for fame and admiration. In the last few weeks of her life, when Lotringer visited her at the clinic, she asked him, “Do you think they’ll make a film about me?”

Kathy Acker grew up on New York’s Upper East Side, attended the “white gloves” but intellectually mediocre Lenox School before attending Brandeis and marrying Bob Acker while still in college. She followed her husband to San Diego, where she finished her BA at UC San Diego and audited creative writing classes with David Antin. In those classes, she first experimented with the plagiaristic technique that would become her signature. After her rise through the underground art scene in New York and her 1983 breakthrough, a 1989 plagiarism suit tarnished Acker’s reputation, and the critical tide turned against her. She spent down her inheritance and struggled to find a university teaching position. These moments act as guideposts in Kraus’s biography, moments on a timeline dappled by the dramas of high school rivalries, her time working a sex show in Times Square with then-lover Len Neufeld, the deaths of her mother and grandmother, and her mother’s purported attempt to abort her, all of which recur in her writing. Shifting between metaphor, memory, mourning, and mythology, Acker collapsed the distance between her life and her work, between her body and her words.

Kraus repeats the notion that Acker dealt in self-made myths, uncovering the truth buried under the fabrications. Acker didn’t study with famed Frankfurt School philosopher and critical theorist Herbert Marcuse. Literary theorist Roman Jakobson didn’t read her undergraduate papers. Yet, as Kraus writes, “[T]o lie is to try. Like most fabulations, the story contains a kernel of truth, or at least of desire.” One expects that this will become the story, that one will learn not so much about Acker’s life but about the myth of the myth, about how we are all constructed selves, a collection of stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, screens with nothing behind them. From this perspective, the story of Acker’s life would be a story of stories, a life viewed in the endless refraction of opposing mirrors. Thankfully, this is not the case. Instead, Kraus gives us an authoritative, narratively engaging, and highly readable story of a remarkable life. One that we might even recognize.

Critics don’t tend to think of Acker’s work as autobiographical. Her cut-up practice and stylized aesthetic, characterized by repetition, expletives, and irregular punctuation, obscures the real life at the heart of her corpus. Though Acker rehearsed her life story in her fiction and public persona, she remains a highly unreliable narrator. As Kraus notes, scholars regularly cite the myths Acker perpetuated in her life as if they were facts. In tackling those myths, After Kathy Acker will be required reading for Acker scholars and enthusiasts alike. The biographical clarity Kraus provides will also, I am sure, teach us new ways to read Acker’s novels, which are dense with intertextual references, excerpts from her diaries, and shocking scenes of sex and violence.

Rather than just providing historical background for Acker’s readers, Kraus uses biography to elucidate her aesthetics and offer a more thorough accounting of her avant-garde lineage. In highlighting her relationships to the conceptual artist Eleanor Antin and the poet Bernadette Mayer, as well as the dense social networks of musicians, writers, and artists that constituted her coterie, Kraus emphasizes the social embeddedness of Acker’s writing. In Eleanor Antin, the wife of Acker’s teacher David Antin, she found a lifelong friend, role model, and entrée into the conceptual art scene. When Acker began to circulate her first publication, The Childlike Life of the Black Tarantula, she used Eleanor’s mailing list for her photography series 100 Boots. Bernadette Mayer, who was already a fixture in the New York underground scene by the time Acker gained a foothold in it, engaged in the same kind of systematic and durational writing experiments as Acker, and was often the recipient of long, overly personal letters from the fledgling artist. While her relationships with male mentors and interlocutors tend to receive more critical attention, After Kathy Acker does the quiet feminist work of restoring to view the women that played an important role in Acker’s aesthetic and intellectual development.

The social nature of Acker’s writing is also a bodily practice, a way of “accessing [the] fleshy, emotive fragments of female experience within a framework of formalist rigor.” When Acker writes her life experiences over and over again, flesh, form, and myth meet. By repeating and reworking her journal entries, her self-imposed formal limitations allowed her to produce a visceral experience of everyday life that hardened into myth. Kraus’s exhaustive archival research helps readers locate Acker’s life in her work, as when she demonstrates how the opening scene of Blood and Guts in High School is drawn directly from her breakup with the avant-garde composer Peter Gordon. Tracking passages from Acker’s diaries that appear in the opening of Blood and Guts, Kraus shows that the argument between Janey, the protagonist, and her father (who, in classic Acker style, is also her lover) is an almost direct transcript of a conversation between Acker and Gordon. In addition to locating biographical source material for Acker’s work, Kraus traces Acker’s life as it emerges in her style. In a smart discussion of Acker’s use of colons, for instance, Kraus shows how the colon functions as a memorial to her mother: “working through […] grief by way of strands of knowledge and consciousness, the colon is used as a summoning.” At such moments, Kraus illuminates the autofictional textures of Acker’s life not as a series of obscured relations between reality and representation but rather as an archive of encounter by which history, language, and syntax negotiate the chasm between life and literature.

After Kathy Acker makes sense of Acker’s life by situating her among her various people and works. In such a thorough accounting, Kraus risks simplifying the relationship between life and art. In a dizzying parade of names and texts, she links Acker’s aesthetic practice to her correspondence with writer-mentors. From Jerome Rothenberg, to whom Acker sent drafts of Politics, to the filmmaker Peter Wollen, who was the addressee of Don Quixote, Kraus claims that “each time Acker worked on a project, she selected, perhaps unconsciously, a ‘silent partner’ as her ideal reader: a confidant, always male, who would serve as an oblique addressee. […] But as soon as her first flush of fame hit, she stopped.” The correspondence Kraus identifies might seem to reduce Acker’s artistic practice to something flippant: her books are just letters to boys. But the restraint with which Kraus shares this information, the descriptive practice that seeks to inform, rather than interpret, raises interesting questions about the relationship between author and audience, about the erotics of writing, and about how those small, insignificant things like crushes and sex and identity and friendship are central to an avant-garde aesthetic practice.

The humanizing details that characterize After Kathy Acker are manna for a certain kind of feminist reader in 2017. I was thrilled to learn that Acker once lived in an apartment owned by the conceptual artist Jenny Holzer and wore a lot of Comme des Garçons. She worked out with Lisa Lyon, a celebrity bodybuilder who collaborated with Robert Mapplethorpe. She fucked Peter Wollen right under the nose of Wollen’s collaborator, the celebrated feminist film critic Laura Mulvey. She hung out with William Burroughs, the novelist Dodie Bellamy, and Kraus herself. The biography offers insights for both the casual Acker fan and deep devotees like myself. When I was looking through Acker’s archive at Duke a few years ago, I came across beautiful illustrations of fish and flowers that, at the time, I admired but couldn’t quite place. Now, I know they were plans for Acker’s tattoos, inspired by Ed Hardy. (For anyone longing for more of these morsels, Dodie Bellamy’s essay “Digging Through Kathy Acker’s Stuff” also offers rich rewards.)

The sense of Acker as a straddler of worlds and affects — networked into rarefied avant-garde coteries but obsessing over her high school rivals; looking up to Patti Smith with the eyes of an unknown fan before she became a similar figure of idol worship for others — enriches the image of Acker as fragmenter of identities. In these moments, Acker emerges as not just a two-dimensional pastiche or intellectual lioness, but as another sweaty body huddled next to you at a crowded poetry reading. After Kathy Acker also extends the subject’s network forward, making the figures she influenced just as important as those who influenced her. Late in the book, Kraus connects the “before” and “after” of Kathy Acker by juxtaposing the responses of old acquaintances with those of younger fans. In Barbara Caspar’s 2007 film Who’s Afraid of Kathy Acker?, Acker’s young readers say things like, “I think I learned a lot about myself, some things I didn’t wanna know, and some things I did.” Kraus maps a similar feeling by reference to Martha Rosler, a contemporary and romantic rival of Acker’s, who observed: “I could’ve been Kathy. Kathy could’ve been me, I don’t know.”

After Kathy Acker allows readers to feel like they could have been Kathy, without feeling like they possess her. When I think about Kathy designing a new tattoo, sitting down to write, selling her Ikea furniture, or writing tone-deaf letters to Bernadette Mayer, I feel a kind of intimacy with her, one that is quite different from the dark and wonderful thrill of reading her fiction. We are after Kathy Acker, in both senses of that word: the inhabitants of a literary landscape that has largely moved beyond her experimental aesthetic, but one that also includes a number of writers — Kate Zambreno, the Riot Grrrl singer Kathleen Hanna, the critic and writer Lynne Tillman, Dodie Bellamy, and Chris Kraus, among others — who are inheritors of her craft. Myths and biographies are art made of lives. Like Acker, Chris Kraus has made big art from a big life.

¤

LARB Contributor

Anna Ioanes is a Marion L. Brittain Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at Georgia Tech. Her scholarship focuses on 20th- and 21st-century American literature and visual culture and has appeared or is forthcoming in Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society and the minnesota review. She is co-editor, with Douglas Dowland, of Violent Feelings, a special issue of LIT: Literature Interpretation Theory, and co-editor, with Andrew Marzoni, of TECHStyle, an online forum for research in digital humanities and pedagogy.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Literary Violence

Brad Evans speaks with Tom McCarthy. A conversation in Brad Evans’s "Histories of Violence" series.

Chris Kraus and the K-Word

So far, Chris Kraus’s new position in the mainstream orbit of Jill Soloway hasn't produced an assessment of the Jewish questions that pervade Kraus’s...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!