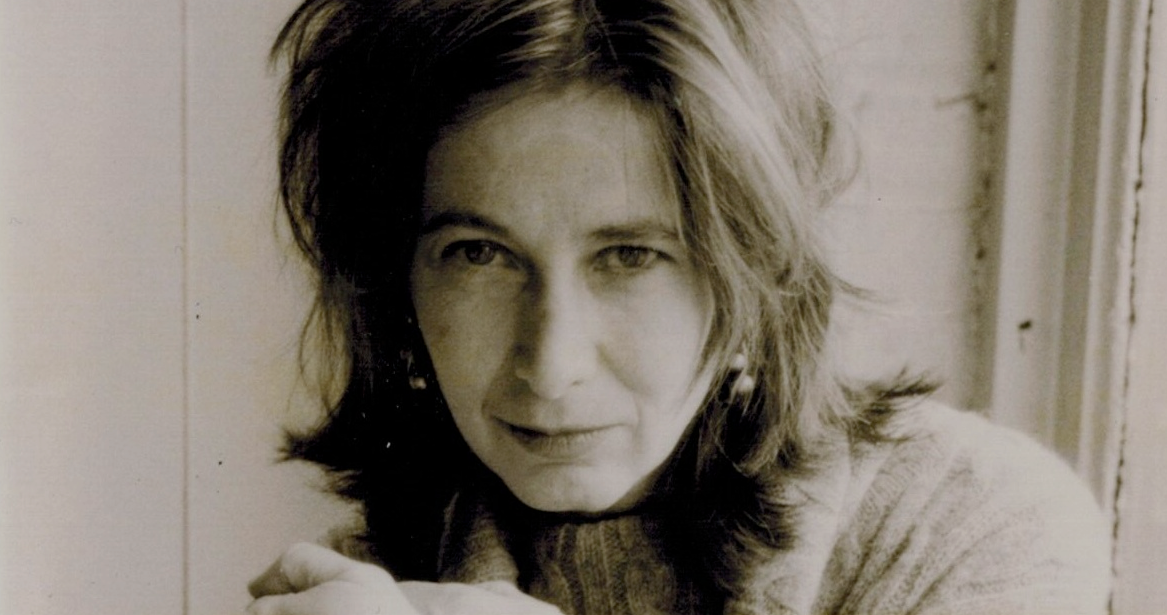

Chris Kraus and the K-Word

So far, Chris Kraus’s new position in the mainstream orbit of Jill Soloway hasn't produced an assessment of the Jewish questions that pervade Kraus’s books.

By Rebecca SonkinAugust 5, 2016

WHAT IS AN AUTHOR DOING when she calls her Holocaust-survivor husband “a kike” in print? What is this same author doing when she names a book chapter about a painter who engaged themes of the Nazi extermination attempt on the Jews, “Kike Art”? And what is this author doing when she writes, “I didn’t really know I was a kike ’til I was 21”?

The author in question is Chris Kraus, and the three k-word quotations are among many that appear in I Love Dick, the 1997 cult classic on the verge of mainstream recognition with a television adaptation by Jill Soloway (the creator and director of the series Transparent) due out on Amazon on August 19.

Writers from Eileen Myles to Leslie Jamison have heaped praise on the book version of I Love Dick, applauding the author’s transformational approach to feminism, female abjection, and the compromised condition of women who are artists who love men. Based on a real-life romantic crush and its attendant aftermath, I Love Dick revolves around the masses of love letters that Kraus wrote to the cultural critic Dick Hebdige, with the gleeful encouragement and participation of her husband, French scholar Sylvère Lotringer. This collaborative aspect of the couple’s letter-writing campaign is as key to Lotringer’s agenda as its role in getting him laid after two sexless years of marriage.

Kraus explores Chris’s life with Sylvère in two other books as well: the theoretical travelogue Aliens & Anorexia (2000) and the novel Torpor (2006), in which the couple’s alter egos are called Sylvie and Jerome. All three books pulse to a striking degree with Jewish themes, including diaspora, money, and abiding obsessions with Jewish identity, history, and the Holocaust. Yet in the considerable critical discourse surrounding Kraus’s slim yet dense oeuvre, what is surprising is what isn’t there at all: an acknowledgment of, and reflection upon, Kraus’s unorthodox treatment of Jews and Jewishness. Most startling is the universal neglect of Kraus’s brazen and prolific use of the k-word, a pejorative many Jews consider as offensive as the “n-word,” though it has largely fallen out of use. The refusal, or disinterest, in calling out Kraus, or in scrutinizing her motives, appeared primed for a correction when the news broke in February that Soloway signed a deal to adapt I Love Dick for the small screen — Transparent, after all, has been described as the Jewiest show on television, one that normalizes Shabbat dinner, shivah, and a fuckable rabbi while twinning eternal Jewish otherness with the legacies of Weimar-era flamboyance and the Nazis’ fatal intolerance of difference.

So far, however, Kraus’s newfound position in the highly visible, mainstream orbit of Jill Soloway has failed to produce an assessment of the Jewish questions that pervade Kraus’s books and the ways they appear to diverge from the warm, unambiguous embrace of Jewishness in Soloway’s work. From Slate to Vulture to Tablet — the online destination of “Jewish news, ideas and culture” — the enthusiasm over the Kraus-Soloway collaboration has thus far been limited to the intersecting feminist agendas of each artist, a legitimate if easy angle on work that is deliberately, forcefully, more textured and complicated.

To borrow a word that Jews most often associate with Maimonides, the great Jewish thinker of the 12th century, I feel perplexed, as much by Kraus’s treatment of Jewishness as by the lit-crit silence surrounding the virtues and vexations of her approach. It is a phenomenon that strikes me as falling somewhere along a spectrum of an aversion to confronting material that is controversial, even uncool in certain realms, and an oversight that is by turns lazy and dangerous among an adoring readership.

Kraus’s typically Jewish preoccupation with her own Jewishness, and that of her now-ex-husband, situates Kraus as an important, if unlikely hinge figure in the Jewish-American literary tradition. In April, Morris Dickstein in the Times Literary Supplement, described the essential character traits of the Jewish-American literary tradition: “The work of the post-war writers was often deployed around a loosely autobiographical protagonist — a Herzog, a Portnoy, suffering in extremis, wallowing in self-pity, oscillating between accusation and anguish.”

In the likewise meta-fictive I Love Dick, the main character is named Chris Kraus. Other characters bear the names of Kraus’s true-life family members, friends, and foes. The main events are based on actual incidents, to what extent she and others have been cagey or silent. But Kraus goes further than Saul Bellow and Philip Roth; by refusing to categorize the book as either fiction or nonfiction, and instead as one that “tore the veil that separates fiction from reality,” readers, and perhaps even Kraus herself, can never be sure what is real and what is not. Critics from Joan Hawkins to David Rimanelli have speculated that details about the real-life Dick have been blurred to avoid a lawsuit. But Kraus has suggested a more theoretical, post-structuralist rationale, stating in an interview in The Brooklyn Rail, “As soon as you write something down, it’s fiction.”

Eileen Myles, who has been Jill Soloway’s partner since last year, writes in the 2006 preface to I Love Dick: “For Chris, marching boldly into self-abasement and self-advertisement [….] was exactly the ticket that solidified and dignified the pathos of her life’s romantic voyage.” Could it be that Kraus is the female Jewish schlemiel, an awkward and unlucky person — insecure, emotionally hungry, self-obsessed — for whom things never turn out right?

In the book, “Chris” is a failed filmmaker, “producing dense and difficult, unlikeable experimental movies, exhibiting them in clubs and venues where projectors broke and people talked and heckled.” Despite her marginal status and finances, she can continue her artistic pursuits, without the distractions of a day job, due to the residual benefits of her husband’s position as a high-profile professor in the French department at Columbia. Hers is a simultaneously enviable and humiliating existence for an artist struggling to find her own voice: Sylvère has told her he has only agreed to marriage so that she can access his health insurance. There are also the assorted freelance gigs that result from her proximity to his reputation, though when the gigs are well paid and prestigious, Chris does the work and Sylvère takes the credit. In the looks department, she describes herself as flat chested with “rodent features.” In the maternity department, she has had three abortions during her relationship with Sylvère, even though she claims that she really wants a baby.

As in the novels of the great postwar Jewish-American writers, sex — the messy, awkward, unambivalent kind — is the realm in which the genre’s potent duo of comedy and calamity find their most fruitful outlet. Chris and her husband haven’t had sex with each other or, as they sheepishly admit to Dick, with anybody else in years. The only way they appear able to rouse themselves is in their intellectual art-project pursuit of a man who spurns Chris’s epistolary advances but whom Sylvère must court on a professional basis. Almost as soon as Chris and Sylvère start writing love letters to Dick — 70 pages overnight — they start having lots of sex together. Midway through the book, when Chris leaves Sylvère and lands a sex date at Dick’s place, the experience reads as funny and exhilarating until it turns demeaning and cruel.

Like her macho, horny male predecessors, Kraus understands sexual connection as fundamental to the triumphs and failures of human connection, no matter how halting, humiliating, or repugnant the sex may be. By narrating the female perspective, Kraus inverts the power structure. She’s absconded with the male chutzpah of the pursuit, hazarding self-abasement in order to fulfill her desires. But if good feminists refuse such risks, Kraus, in turn, refuses that assumption. “[Dick] asked me why I made myself so vulnerable. Was I a masochist? I told him No. ‘Cause don’t you see? Everything that’s happened here to me has happened only cause I’ve willed it.’”

Kraus might be hurt by Dick’s dismissiveness and unsurprised by his post-sex rejection. Rather than skulk away in silence, Kraus, like Herzog and Portnoy before her, seizes control by going public with her side of the story. What’s more, she tells it funny. En route to her sex date, Chris pees into a half-drunk styrofoam cup of coffee while buckled into the driver’s seat, so that she can avoid heading straight for the toilet when she walks into Dick’s house. To keep from littering, she tips the cup’s contents out the window and proceeds to spill the evidence all over her hands. “Dear Dick,” she writes, “sometimes there just isn’t a right answer.” Arriving late, she blunders foreplay by steering the conversation toward torture, genocide, and the Guatemalan Coca-Cola strike. Even the echt-schlemiel, Woody Allen, made sure he was sleeping with Annie Hall before taking her to see The Sorrow and the Pity.

Kraus’s approach to her own Jewishness is the other key to her hinge position between generations of Jewish-American authors. According to Morris Dickstein in the TLS, today’s Jewish writers are “more unambiguously comfortable in their Jewishness than were their predecessors.” The older generation were American–born, mostly men, who were raised by poor immigrants in ethnic ghettos. They rebelled by bedding blond shikse bombshells while shoving aside the persecuted European past of their parents. Kraus experienced a different upbringing than either type. Born in New York and raised in New Zealand, Kraus claims she learned she was Jewish when she returned to Manhattan at age 21. A bad girl of the first order, she purportedly danced topless and gave blow jobs in the bathroom of Max’s Kansas City in an effort to score free coke and earn cash to fund her performance art. Later, she executed the definitive good-Jew deed by marrying a Holocaust survivor, the holy grail of the contemporary Jewish mensch.

Kraus betrays one major digression from the couple’s Jewiness: Sylvère and Chris are “militantly opposed to psychoanalysis.” This makes sense due to a strange coincidence about Chris and Sylvère. Each, for different reasons, is a Jew without memory or history, a condition inimical to a people whose every holiday is an exhortation “to remember,” whether enslavement in Egypt or yet another failed extermination attempt. Chris has no childhood history of Jewishness: “Oh, there’d been intimations,” she writes in I Love Dick.

I picked Wendy Winer, one of 6 or 7 Jews, as my best friend out of 2000 kids in our little redneck town. My only significant New Zealand boyfriends were named Rosenberg and Meltzer. The single out’ed Jew in my grade-school class, Lee Nadel, was taunted by the entire school as “Needle Nose.” Perhaps my parents, who both attended Christian church, were just trying to protect me.

Perhaps local anti-Semitism — or was it self-loathing? — explains her parents’ choice to anoint Chris with the most Christian name available.

Sylvère’s own Jewish-historical amnesia might seem counterintuitive, except that it is common among very young child survivors, especially for those who spent the war hiding in the countryside. To his sorrow and embarrassment, Sylvère’s memories of the Holocaust are reduced to little more than the day his father was taken by the Nazis, as well as the anti-Semitic aftermath of 1950s France, when ambitious Jews suffered the social dilemma of whether to announce their Jewishness to offset possible racial slurs and be accused of “flaunting it” or say nothing and be accused of “hiding it.”

In Torpor, Kraus describes the amnesiac survivor’s guilty obsession: “Why, Sylvie wonders, does Jerome torture himself by reading every piece of Holo-porn? He’d never been a prisoner himself. Why does he let these simulated memories of the camps define his every action?” The answer lies in the framed black-and-white photograph of his mother taken a few weeks into the German Occupation. Her yellow Star of David is partly hidden by her jacket’s large lapel. Jerome takes the picture with him wherever he goes because it makes him think of “History.”

Chris and Sylvère’s mutual craving for history is an early source of connection. Their first night together, Chris asks Sylvère if he ever thinks about history. “‘All the time,’ Sylvère replied, thinking about the Holocaust. It was then she fell in love with him.” “Bad History,” a term of Sylvère’s survivor friend Georges Perec, and its seepage into the present and future, is Chris and Sylvère’s ultimate undoing.

Despite a childhood spent outside the Jewish mainstream, Kraus has mastered all of its tropes. Of aggressive Jews, Kraus writes: “Sylvère and Chris bumbled around the construction site that was their house ‘helping’ Tad and Pam, non-Jews who mistook their constant screaming at each other for hostility.” Of demanding Jews: “I was a New York Jew, entitled to seek value for my money.” Of cheap Jews: “Jerome has a special treat in store. He’s discovered how to beat the fare!” Of communal expectations among Jews of the diaspora: “Why had she and Jerome been perceived as child-like hicks by Dr. Silverstein, and not as fellow Jews?” And of German-despising Jews: “Yes, he thinks, Berlin has been incredible. The artists actually support each other. But these impressions of mere individuals haven’t changed his hatred of the German race.”

Theories abound over the origins of the k-word, itself a kind of bad history. One holds that as illiterate Jews entered the United States at Ellis Island, they signed the entry forms with a circle, rather than the customary “X,” which they associated with Christianity. Since “circle” in Yiddish is kikel, it’s said that immigration officers called anyone who signed with a circle a kikel, and more succinctly, kike. Other hypotheses trace the pejorative’s emergence to 1860s-era England where “Ike,” a nickname for the common Jewish name of Isaac, gradually became kike. The earliest reference I could find goes back to a 16th-century church prohibition on study of the Talmud, in which Pope Clement VIII referenced the “blind (Latin: caeca) obstinacy” of the Jews. According to this line of thought, caeca eventually became kike.

Whatever the word’s origins, Kraus deploys the pejorative with neither explanation, nor apology, on herself, on Sylvère, on R. B. Kitaj and his paintings, which engage themes of the Holocaust. Beyond an apparent attempt at describing an otherness, or alienation, inherent to the Jew, Kraus’s intent for the k-word remains opaque, as much for its datedness as its inconsistency. Why, for example, would an avant-gardist attempt to resuscitate a pejorative so passé that many of her younger readers may not know its meaning? And why not label as “kikes” Eleanor Antin and Hannah Wilke, the two other visual artists profiled in I Love Dick? Wilke, held up as an example of male erasure and resulting art-world alienation, was the granddaughter of Jewish immigrants. Antin, another feminist practitioner of the funny and outrageous, is the daughter of a Yiddish film actress and has made her own films parodying the genre.

Two of Kraus’s favorite subjects are the interrelated ideas of seizing control by “marching boldly into self-abasement” and “who gets to speak and why.” As a woman and “failed filmmaker,” Chris gets to speak once she embraces the humiliation of her circumstances and turns them into a vessel for her over-the-top, searing sense of humor. As a Jew, the effect of embracing the k-word is less convincing. Kraus never manages to locate a source of truth or hilarity beyond the shock value. Shock value for its own sake seems too juvenile an objective for an artist of Kraus’s caliber. And draining the ugliness of the pejorative through usage seems too unoriginal.

In Judaism, there is a concept called lashon nekiah, which means “clean language.” The idea is not to whitewash, nor to endorse an aesthetics of prissiness or purity, but rather to render difficult or so-called dirty subjects accessible. The intent is a strategic sleight of hand, construed to get us to engage the hard questions we’d all prefer to avoid. A classic example is “Semahot.” One of the earliest texts outlining Jewish laws of death and mourning, “Semahot,” which translates literally as celebrations, is a euphemism for sorrows. But who would open a book with a title like that?

If the absence of the k-word in the discourse surrounding Kraus’s work is indicative, the use of dirty language to expose a dirty subject has backfired. By employing the dirtiest language around the dirty subject of anti-Semitism, Kraus has shut down the discussion rather than open it up. It is a perplexing turn of events for an artist who demands to be heard.

Yet Kraus’s missed opportunity might get a second chance in the hands of Jill Soloway. As one of our most adept practitioners of lashon nekiah, Soloway made trans identity mainstream. If she can complete Kraus’s failed mission, she will have turned out to be the perfect small-screen interpreter of I Love Dick. The feminist part of the program will be easy, not only because it’s where Kraus succeeds but also because it’s where she gets her laughs. But the Jewish question? There’s no easy solution.

¤

LARB Contributor

Rebecca Sonkin, an MFA candidate in creative nonfiction at Columbia University, is director of Columbia Artists/Teachers and translation editor of Columbia: A Journal.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!