What Rubbish They Publish

By Bob BlaisdellJuly 20, 2015

The Prank: The Best of Young Chekhov by Anton Chekhov

IT'S TRUE THAT CHEKHOV, gathering his work for collected editions, essentially renounced these stories by excluding all of them. But when he was 22 and trying to get The Prank (Шалость) okayed by the Moscow censor in 1882, he was mighty proud of them. By the time he submitted the book, he had published several dozen stories and skits in Moscow and Petersburg humor magazines. These dozen, with two of the best on either end, he selected and ordered, and his brother Nikolay, only two years older but already a well-known artist, contributed the spirited and risqué illustrations.

Anton was the third son, but even at 19 he was his family’s savior, arriving in Moscow from Taganrog, their hometown on the Black Sea, to join his parents and younger siblings. (While his father fled creditors, Anton had stayed behind to finish school and to tutor and earn money.) His two older brothers, talented and careless, prey to drink, couldn’t stay out of their own ways. When the censors nixed the volume twice, Chekhov gave up on it; he was already publishing in bigger humor magazines. While in medical school for five years, attending classes and clinics more regularly than most students, Chekhov wrote and published several hundred short stories and skits, supporting the entire family and eventually making his parents quite comfortable.

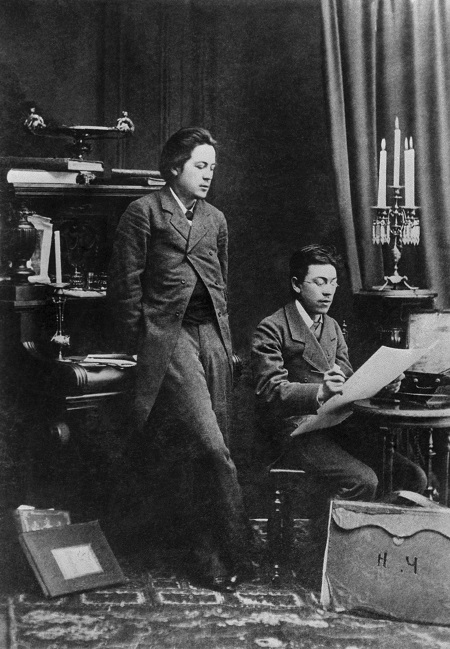

No doubt, when the New York Review of Books introduces its publication of this title, its pages it will include, as the original book did not, the staged photograph of Anton and Nikolay, with Anton standing and looking over the seated and studiously working Nikolay’s shoulder:

In those years, says a biographer, Chekhov’s “voice was a low baritone with a soft timbre; his contemporaries remembered especially when he was excited in a conversation, his brown eyes lit up, shone, and flashed, and on his lips twinkled a quick smile.” He was as handsome as Keanu Reeves (and, by my account, 245 times as talented).

There are few letters from those days, but he was quite himself: quick and funny, highly juiced. The excited 20-year-old, having begun to make his way in the world, tells a friend, “Move to Moscow!!! I terribly love Moscow. Whoever gets used to her will not leave her. I will forever be a Moscovite … Come!!! Everything’s cheap. Buy trousers for 10 kopecks!” Who among the pantless wouldn’t come running?

One editor who occasionally published Chekhov from 1880 to 1882 posted a note to Chekhov in the magazine’s contributors’ box (this was how freelancers heard whether their pieces were accepted or not!): “You are withering without having flowered.” The British biographer Ronald Hingley doesn’t blame the editor, however, and takes no delight in these stories:

How far Chekhov was from discovering an identity in 1880 is symbolized by the signatures to his ten short publications of that year, all in Strekoza [Dragonfly]. These have seven different pseudonyms distributed among them. Mostly variations on the Christian name “Anton” and the jocular school nickname “Chekhonte,” they include the combination “Antosha Chekhonte,” his best-known pen name.

Hingley begrudges Chekhov the pen names, but Chekhov, his identity firmly in place, thought them amusing, and so can we.

Not that Hingley or anybody else knew or cared about The Prank until the scholar M. P. Gromov found it in 1967 in an archive at the pre-Soviet Moscow censorship office. Gromov points out that Chekhov “told no one anything about his first book and never wrote about it, and its fate was left secret from even those very close to him — his sister, his wife and brothers.” Gromov was able to compare the drafts from the magazines and the manuscript, and noted that, “for the book, Chekhov reworked, strengthened, corrected and polished the stories.”

Chekhov, unlike 99 percent of us who have admired him, never allowed himself to write autobiographical stories; he could use an experience from his life only if he replaced himself with an unlike character. And yet the stories here (and the famous and stupendous ones later) often seem close to home. In almost every story, we sense Chekhov upstage or in the wings. In “Artists' Wives,” the protagonist's wife, who regularly falls asleep reading his manuscripts, wonders aloud when he receives yet another rejection note: “What rubbish they publish, and yet they hardly publish you. Astounding!”

At 19, Chekhov had the pluck of a determined writer, and he figured out how to get the format right while being funny, and how to dash off stories in a wink in order to earn enough to move his struggling family out of the red-light district. Like a skilled bowman, or Steph Curry, he hit his target more and more often. It’s fun to see him zipping and quipping in these earliest stories, most of which are unfamiliar to English readers.

In “Flying Islands by Jules Verne,” Chekov parodies the Frenchman’s popular science fiction novels: “John Lund was a Scotsman by birth. He had received no education whatsoever and he had never studied anything, yet he knew everything there was to know.” Later in the story, Chekhov’s narrator, the supposed translator into Russian, meets Verne’s tediousness with a recurring joke:

The observatory to which Bolvanius escorted Lund and old Tom Snipe … (Here follows an extremely lengthy and extremely dull description of the observatory, which the translator has decided to omit in order to save time and space.) There stood the telescope perfected by Bolvanius.

Chekhov’s literary idol, Lev Tolstoy, like tens of thousands of other Russians in the 1880s, thought Chekhov’s stories were hilarious. One of Tolstoy’s daughters remembered that her father

much preferred Chekhov's stories to all his other works. Quite often, at Yasnaya Polyana, the whole family would sit around the great circular table, lit by a big white lamp overhead, while he read them to us.

And though he was an excellent reader, I am afraid that when reading Chekhov my father was sometimes quite unable to go on, so infectious did his helpless fits of laughter become.

“Oh how charming that is!” he would exclaim as he laughed till he cried. “How is it Chekhov can't see that the most priceless part of his art is the humor? A humorist like him is the very rarest of things.”

Chekhov was so good at comedy that literary editors encouraged him to go straight, and in his own crooked way he did. By the old age of 25, he began allowing the stories to unwind irresolutely, to let the characters make their way, complaining or not, through love affairs, mental illness, laziness, idealism, boredom, recklessness, and fecklessness.

Young or middle-aged, Chekhov noticed everything, and his dialogue in these early stories is as good and funny as anything later. In “Papa” (“Папаша,” 1880), a father pays a call on his lazy son’s math teacher: “’I came […] to have a talk with you, sir. Yes. You’ll have to forgive me, of course. I’m no speechifier. My kind, you know, speaks plainly and directly.’ He laughed.” Chekhov indicates Papa’s nervous and annoying manner here with “ха-ха-ха,” pronounced “ha-ha-ha,” and later with “хе-хе-хе” (he-he-he); the common Russian verb for fulsome laughter is the onomatopoeic хохотать, pronounced “ho-ho-tat.” (Our verb “laugh” doesn’t laugh; chortle, on the other hand, comes closer to imitating the sound and suggesting the merriness of “ho-ho-tat.’”) He asks the teacher:

“Did you attend university?”

“I did.”

“Right! My, it’s hot today. Ivan Fedorovich, you’ve given my boy a heap of Fs. Which is all right, you know. It’s according to one’s deserts. Yes … Tribute to whom tribute is due, and a lesson to whom a lesson is due.” He laughed [no, no; Chekhov gives us Papa’s “he-he-he”]. “Still, it’s unpleasant, you know. Do you mean to say that my son really doesn’t understand math?”

“How should I put it? It’s not that he doesn’t understand it as such, it’s, you see, well, he doesn’t study. So, no, he doesn’t understand.”

“And why not?”

The teacher raised his eyebrows [or literally, “The teacher made big eyes”]. “What do you mean, why?” he said. “He doesn’t understand, and he doesn’t because he doesn’t study.”

Teachers know this kind of maddening circularity is actually how such meetings go!

Chekhov often makes fun of our pretensions, especially of us writers. In “A Confession, or, Olya, Zhenya, Zoya (A Letter),” the 39-year-old unmarried narrator sets out to explain how he’s lost all 15 loves of his life, through no fault of his own, but only because of chance (“chance is a despot”). He will run out of steam narrating his mishaps and cut out after telling us of only four — but as he unconsciously reveals himself, we know his sort (if we look in the mirror) all too well:

Dear friend, you know of course that I am a writer. The gods have ignited their sacred flame within my breast. I have no right but to take up the pen. I am Apollo’s votary. Every beat of my heart, my each and every sigh, in short, all of me, I offer as a sacrifice upon the Muses’ altar! I write and write and write. Take away my pen and I’m dead. You laugh, you don’t believe me. I swear that it’s true!

The translation is fine but a little less funny than the original. Chekhov just bounces in Russian; there’s a liveliness (a chortle, if you will) in the phrasing that makes me smile. Chekhov “is a strange writer,” Tolstoy told a friend; “he throws words about as if at random, and yet everything is alive.”

Bloshteyn’s introduction and translator’s note are excellent. Her only sin is one of omission, not mentioning her future rival in regard to these stories: the biographer and translator Rosamund Bartlett, trustee of the Anton Chekhov Foundation, who’s done more than any Anglophone lately to promote Chekhov’s earliest work. Bartlett heads the Early Chekhov Translation Project, a collaboration in which all 528 of his pre-1888 stories and skits will be translated. (The first, and perhaps best translator of Chekhov’s stories, Constance Garnett, translated 144 of these and all of the later stories; the last was written in 1903, and Chekhov died of tuberculosis in 1904.) Bartlett’s group will present the stories in chronological order.

In the mean time, Bloshteyn has resurrected a stash that will amuse everyone who loves, in Tolstoy’s words again, “the very rarest of things”: a humorist like Chekhov.

¤

¤

Sources:

antonchekhovfoundation.org/en/translation-project/

Chekhov, Anton Pavlovich. Pis’ma: Tom 1 [Letters: Volume 1]: 1875-1886. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo “Nauka.” 1974. 40 [May 8, 1881] {“Пережай в Москву!!! Я ужасно полюбил Москву. Кто привыкнем к ней, тот не уедет уз нее. Я навсегда Москвич ... Приезжай!!! Все дешево. Штаны купить за гривеник!”}

Goldenweizer, A.B. Talks with Tolstoy. London: Hogarth Press, 1923.

Gromov, Mikhail Petrovich. Chekhov: Zhizn zamechatelnykh liudei [Chekhov: The Life of Remarkable People]. Moscow: Molodaya Gvardiya, 1993. {“Сам А. П. Чехов о первый своей книге никому ничего не говорил и не писал, и судьба ее осталась тайной даже для очень близких ему людей — для сестры, для жены, и братьев.”} 114 {“Для книги Чехов их переработал--усилил, выправил, отшлифовал.”}

Hingley, Ronald. A Life of Anton Chekhov. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Kuzicheva, Alevtina Pavlovna. Chekhov: Zhizn’ “Otdel’nogo Cheloveka.” [Chekhov: The Life “Of an Individual”]. Moscow: Molodaya Gvardiya, 2012. {“Голос — низкий баротон мягокого тембра. Современники запомнили особенность: когда его что-то захватывало в собеседнике, в общем разговоре карие глаза вспыхували, светили и начинали лучиться, и на гувах мелькала быстрая улыбка.”}

Sukhotina-Tolstaia, Tatyana. Tolstoy Remembered. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977.

LARB Contributor

LARB Staff Recommendations

An Anna Is an Anna Is an Anna

Translators of Anna Karenina are wonderful — except for their annoying habit of denigrating the work of earlier ones.

Reading “Anna Karenina” in Beirut

Aaliya builds a life — and walls around herself — out of books in Rabih Alameddine’s An Unnecessary Woman.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!