Reading “Anna Karenina” in Beirut

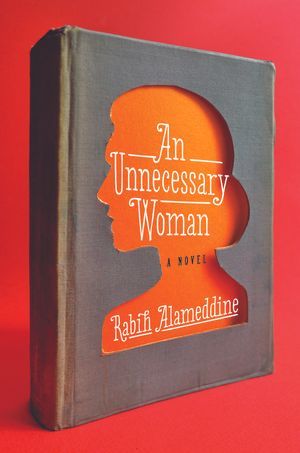

Aaliya builds a life — and walls around herself — out of books in Rabih Alameddine’s An Unnecessary Woman.

By Priyanka KumarMarch 26, 2014

An Unnecessary Woman by Rabih Alameddine. Grove Press. 320 pages.

THE BEVERAGE of choice for aging female intellectuals seems to be tea. Aaliya, the 72-year-old protagonist of Rabih Alameddine’s An Unnecessary Woman, drinks her morning cup before the rest of Beirut sputters to life. Aaliya refuses an offer to drink coffee with “the three witches” — her neighbors — and instead goes to the National Museum to find solitude. A self-educated translator, Aaliya translates books into Arabic from English and French. She decides which new book to begin translating each January first. The novel recalls Muriel Barbery’s The Elegance of the Hedgehog (2008) in which Renée, a concierge in Paris, consumes books, music, and Japanese films and, yes, many cups of green tea. Aaliya loves Anna in Anna Karenina; Renée responds to the music in Tolstoy’s prose. Neither can read Russian.

Aaliya has one friend, Hannah. Both women are unmarried and thus, by the culture’s code, unnecessary. While Aaliya builds herself a life — books and records are her brick and mortar — Hannah devotes herself to the family of a man whom she believes would have proposed if he hadn’t died prematurely. The scarves Hannah knits cannot, in the end, protect her from deep emotional pain. Aaliya protects herself by following Flaubert’s dictum: “Every man guards his heart in a royal chamber. I have sealed mine.” Except Aaliya worries that her “sealant leaks.”

Half the pleasure of reading this novel lies in Aaliya’s musings about other authors, most of whom she admires (though she disses Hemingway), and in quotes she recites habitually from her favorite philosophers. When she weighs in on the Constance Garnett translations of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, she speaks to readers who have been amassing Pevear-Volokhonsky translations (mea culpa). (It should be noted that Alameddine’s arguments echo a 2005 New Yorker article on the same subject.) The many allusions to writers and their quotes can feel like namedropping, but it is not unusual for Aaliya to drop gems: “It was Camus who asserted that American novelists are the only ones who think they need not be intellectuals.” And, without wasting a breath: “One of the things I have in common with the incredible Faulkner is that he didn’t like having his reading interrupted.”

Aaliya hasn’t been in danger of having her reading interrupted for decades. The novel is marked by its absence of onstage family dynamic, by Aaliya’s refusal to participate in the institution of the Lebanese “family: its necessity, its insanity, its quandary, its mystery, and its comfort.” Aaliya knows that Beiruti society isn’t “fond of divorced, childless women.”

Alameddine moves easily between Aaliya’s present and her past. When Aaliya was a young woman, her husband walked out on her. Her family’s response was to harass her, banging on her door in an attempt to get her to vacate her spacious apartment for their use. It’s not surprising that Aaliya prefers a life steeped in literature: “I know Lolita’s mother better than I do mine, and I must say, I feel her more than I feel my mother.”

And yet, one of the more moving scenes in this novel is when Aaliya goes to visit her aged mother at the home of her “half brother the eldest.” She finds the old woman asleep, facing a window; an eternity seems to pass by — filled with Aaliya’s ruminations — before her mother wakes up. With a daughter’s instinct, Aaliya discovers that the overgrown nails on her mother’s feet are causing her pain. With the help of a grandniece, Aaliya gives her mother a footbath (steeped with Lipton teabags) and clips her nails.

The near ascetic tone of An Unnecessary Woman is a shift from the exuberance of Alameddine’s previous novel. In The Hakawati (2008) Alameddine wove the deathbed scenes of the protagonist’s father, and his grandfather’s last years, with fables that could give action films a run for their money. This is not The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Among the concentric circles of stories is one of an Egyptian slave Fatima, an indefatigable DIY-er who goes on a quest to help an emir’s wife conceive a male heir. After a head-spinning trip to the underworld to retrieve her now-missing hand, Fatima prepares to give birth at the same time as the emir’s wife while underworld imps photoshop her room’s décor.

Given the pathological straying in The Hakawati, it is a surprise when the narrator of An Unnecessary Woman asks for permission: “Allow me to stray once more — briefly, I assure you.”

At times, Aaliya does wonder if she’s a speck, a nothing. Though she may have hoped for publication early on — she’s most proud of her translation of Anna Karenina — she now harbors no such illusions. Perhaps it is not so important for us to know whether Aaliya’s translations will find a home. Unlike Tolstoy’s Anna, unlike Barbery’s Renée, Aaliya is left standing (creaky bones, chopped blue hair, and all) at the end of this novel. Aaliya has survived her city’s violence, her family’s apathy, and her gender’s lot; in the face of war and stupidity, she has succeeded in creating an intellectual universe of her own, a life of her own. That Alameddine has given us a woman who can do all this, who is remarkably alive in spite of a smorgasbord of setbacks, is not only a greater gift than the action-figure Fatima of The Hakawati, it is also a significant literary accomplishment.

¤

LARB Contributor

Priyanka Kumar is the author of the widely acclaimed book Conversations with Birds (2022). Her essays and criticism have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Orion, and The Rumpus.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Not Quite Lost in Translation

Lebanese author Rabih Alameddine’s latest novel, An Unnecessary Woman, is a paean to the transformative power of reading.

Forms of Cosmopolitanism

The 150th birthday of Greek poet Constantine P. Cavafy has many celebrating, and debating, his legacy.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!