When Darkness Drains Away: On Virginie Despentes’s “Vernon Subutex 1”

Jennifer Croft is swept away by Frank Wynne’s translation of “Vernon Subutex 1,” a novel by Virginie Despentes.

By Jennifer CroftJanuary 21, 2020

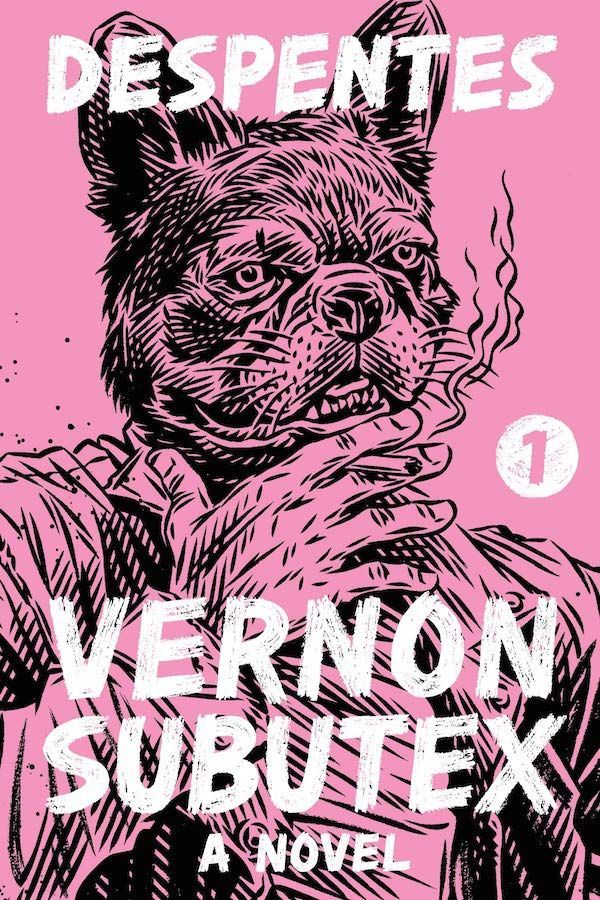

Vernon Subutex 1 by Virginie Despentes. FSG Originals. 352 pages.

THE HISTORY OF LITERATURE in translation is filled with good and bad matches. Great matches — Juliets who get their Romeos, with not a single suicide along the way — are few. The new novel Vernon Subutex 1, written by Virginie Despentes and translated from French by Frank Wynne, is the kind of match that is so great it won’t occur to readers that these two entities — author and translator — might have ever been apart. In fact, their prose is so powerful, and so perfect, that we forget we’re even reading. Opening up Vernon Subutex 1 is more like stepping inside a thrilling, pulsing party and getting instantly mesmerized by the whirling couple at the center of the crowd.

This is the first volume of a trilogy about the last hurrahs of a lovable, unremarkable — except for just one thing — middle-aged man named Vernon Subutex. Vernon used to own a record store, and on the novel’s first page, we learn that he is about to lose the unemployment benefits he’s come to count on in the decade since his store was forced to close. “Vernon was well placed to understand the threat posed by the tsunami that was Napster,” Despentes and Wynne write, “it never occurred to him that the ship would go down with all hands lost.”

After a string of losses that also includes three close friends — to cancer, a car crash, a cocaine-related heart attack — Vernon is now poised to also lose his apartment, because Alex Bleach, the rock star friend who has been paying his back rent, has overdosed in a “champagne-and-prescription-meds coproduction.” (“He was forty-six. Who waits for the onset of menopause, male or female, to die of an overdose?”) When Vernon is indeed evicted, he fills a backpack with a few basic things and the three videocassettes Alex recorded on his last visit, which Vernon hopes to sell.

It is this hasty act that sets in motion the great quest of Despentes’s trilogy. By the end of Volume I, an ever-expanding cast of characters are desperately seeking these tapes for various reasons, including a vile man who fears (justifiably, as the reader will come to understand in Volume II) for his reputation and career if Alex’s truth comes out.

Part of what makes this book so exciting to read is Despentes’s ability to broach so many topics, toggling between them in seamless, almost superhuman fashion. Deftly she tackles sex, materialism, the technologies that are hastening society’s collapse, capitalism, racism, gender fluidity, wounded masculinity, wounded femininity, domestic violence, homelessness, porn, the hypocrisy of the left, and the virulence of the right. Vernon Subutex 1 is about all these things, but it is also about Paris — the people living in the city today, and in particular, those who don’t change when society changes around them.

Despentes writes her characters with such heart, locating in their simplicity a kind of masterful complexity, making them wonderful and mediocre — in other words, human. It is in Wynne’s words that we read them, and Wynne dazzles as Vernon does when finally, as DJ of the drug-infused, almost otherworldly party that comes near the end (the party readers suddenly realize we have been expecting all along), he becomes “the Nadia Comăneci of the playlist.” Wynne is the one who sets the tone of this novel in English, carefully calibrating every person’s lexicon, register, and syntax to accurately render their imagination, to make it effortless for us to understand who they are, how they think, and what they want from themselves and each other. When it comes time for the man who beats his girlfriends, Wynne speeds up, turning poignantly colloquial: “People who never lash out don’t understand how it works. It is a beast crouching in the belly, it moves faster than thought. And once unleashed, it is like a wave: all the goodwill in the world cannot stop it from breaking. It has to come crashing down.”

He seems to whisper, meanwhile, the words of trans model Marcia, an immigrant from Brazil:

This is the first time in years that she has thought of Belo Horizonte and felt the desire to go back in time. Take the young boy-girl she was and whisper in his ear don’t worry you’ll never believe all the things that will happen to you, one day you’ll see, you’ll be so jaded by opulence and easy living, so sated by life you’ll complain that you’re bored. Like a real princess.

If there is such a thing as a villain in this world, then it is Marcia’s lover and benefactor, Kiko, host of the big end-of-novel party; here, too, Wynne’s shapeshifting shines:

The cultural habits of the poor make Kiko want to puke. He imagines being reduced to such a life — over-salted food public transport taking home less than €5,000 a month and buying clothes in a shopping mall. Taking commercial flights and having to wait around in airports sitting on hard seats with nothing to drink no newspapers being treated like shit and having to travel in steerage, being a second-class scumbag, knees jammed against your chin, neighbor’s elbows digging into your ribs. Screwing aging cellulite-riddled meat. Finishing the workweek and having to do the housework and the shopping. Checking the prices of things to see if you can afford them. Kiko couldn’t live like that, he would rob a bank, put a bullet in his head, he would find a solution.

And when the party finally draws to a close, Wynne is magisterially lyrical: “It is not quite dawn, but that curious moment when darkness drains away before the sun has risen.”

Despentes and Wynne are both humble, respectful, graceful, and unbelievably effective at conveying story and ideas. If they felt like it, we feel, they could destroy us. But instead they’ll just tell us this great story that will make us see ourselves and others in a whole new way. And, very fortunately, they’ll keep on dazzling us from the dancefloor for two volumes of Vernon Subutex to come.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jennifer Croft is a writer and translator. She is the author Homesick (Unnamed Press, 2019), which was originally written in Spanish and will be published in Argentina as Serpientes y escaleras in 2021. She was a 2018–’19 Cullman Fellow at the New York Public Library, and is also the recipient of Fulbright, PEN, MacDowell, and National Endowment for the Arts grants and fellowships, as well as the inaugural Michael Henry Heim Prize for Translation and a Tin House Scholarship. She holds a PhD from Northwestern University and an MFA from the University of Iowa. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, n+1, BOMB, VICE, Guernica, Electric Literature, Lit Hub, The New Republic, The Guardian, the Chicago Tribune, and elsewhere.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Shine a Light: Tom Roberge and Emma Ramadan on Selling Uncommon Books

Nathan Scott McNamara talks to Tom Roberge and Emma Ramadan, co-owners of Riffraff, a bookstore, coffee shop, and bar in Providence, Rhode Island.

The Miraculous Bonds and Secrets of “Motherhood”

“Motherhood” offers readers, and women in particular, ingenious ways to reconceive themselves.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!