What Was the Sitcom? On Grace Lavery’s “Closures”

Isabel Bartholomew reviews Grace Lavery’s “Closures: Heterosexuality and the American Sitcom.”

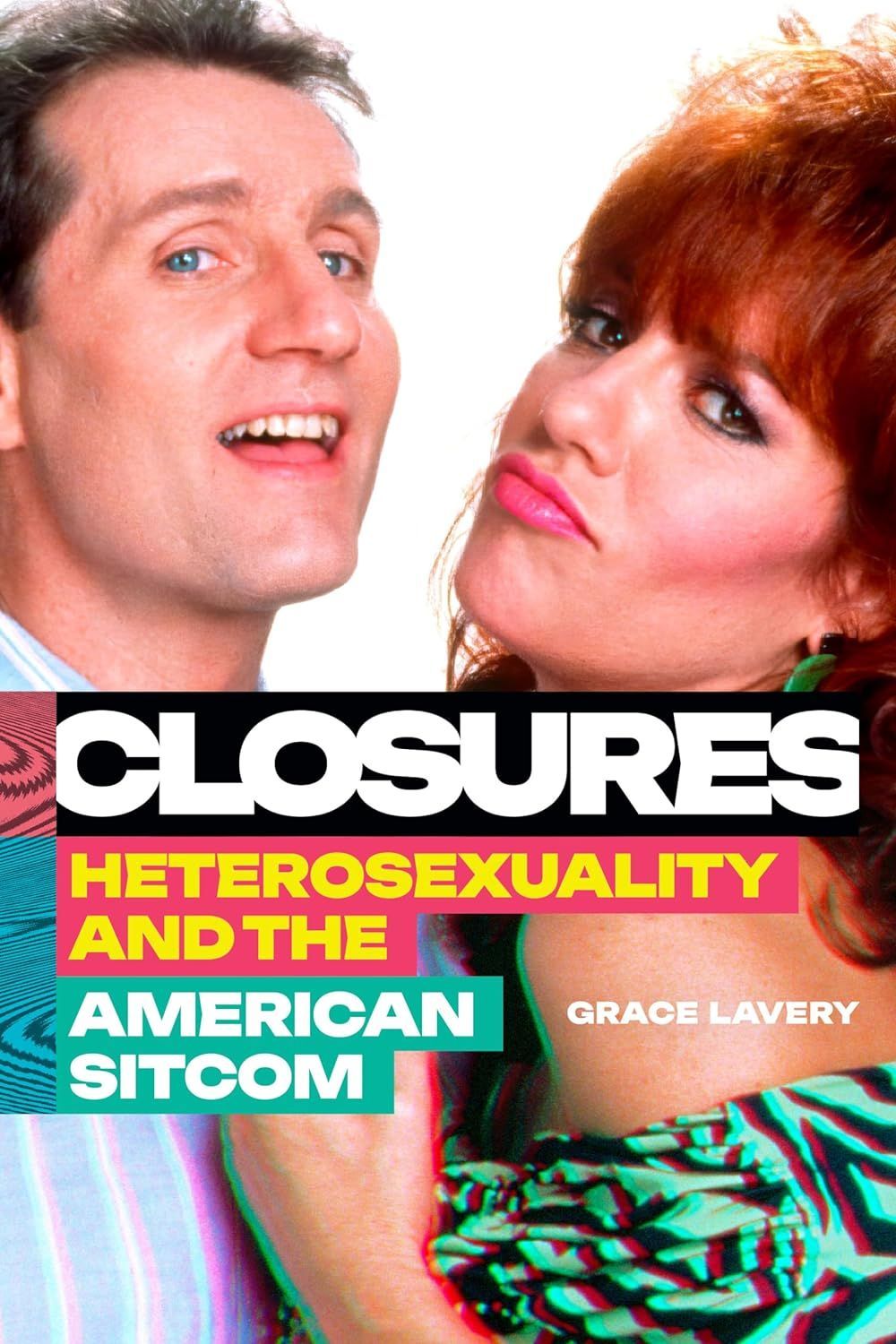

Closures: Heterosexuality and the American Sitcom by Grace Lavery. Duke University Press. 128 pages.

ON THE THIRD season of The Office (2005–13), Pam (Jenna Fischer) invites co-workers to attend the opening of her art show, but few of them come. Pam’s boyfriend, Jim (John Krasinski), makes a perfunctory appearance but demonstrates little interest in the art. Oscar (Oscar Nunez) and Gil (Tom Chick) also attend. Unaware that Pam is standing behind them, the couple criticizes Pam’s drawings—Gil describes them, bitchily, as “motel art.” A dejected Pam begins taking her work down when Michael (Steve Carell) arrives late. He’s genuinely impressed and asks if he can buy one of her drawings of the Dunder Mifflin building. “I am really proud of you,” Michael tells Pam as they share a characteristically awkward hug, Pam’s eyes filling with tears.

Gil is right: Pam’s art is motel art. But Pam’s creative efforts provide the opportunity for a poignant moment with Michael that plays as one between a daughter and her father. The episode legitimates Gil’s queer critique of the middlebrow, the commercial, and the clichéd, while also making a sentimental appeal to “family values.” Moreover, it is as if Michael’s saccharine paternal reassurance responds to and is even necessitated by the queerness of Gil’s critique. Grace Lavery’s new book Closures: Heterosexuality and the American Sitcom argues that similar dynamics have been constitutive of the sitcom for over 50 years. Since its inception, she argues, the sitcom has staged queer disruptions of the heterosexual family, so that the genre can restore that family, over and over again.

Across genres and streaming platforms, our contemporary TV landscape is preoccupied with the family. TV almost always has been, and certainly the prestige melodramas of the last few decades—The Sopranos (1999–2007), Mad Men (2007–15), Breaking Bad (2008–13), Game of Thrones (2011–19), True Detective (2014– ), The Leftovers (2014–17)—have tended to anchor themselves in the affective demands of familial intimacy, even when their broader plot concerns seemingly lie elsewhere. As Michael Szalay has argued, prestige television’s preoccupation with white family life, and the eroding distinction between work and nonwork that now increasingly defines it, was shaped fundamentally by the decline of the family wage in the wake of deindustrialization.

And yet, as any of us could likely attest, the family hasn’t exactly withered away. There are, needless to say, any number of reasons for the nuclear family’s enduring hegemony. In her 2017 book Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism, Melinda Cooper reminds us that Ronald Reagan’s gutting of the social safety net, and Bill Clinton’s subsequent privatization of financial risk and responsibility in the form of household debt, effectively consolidated the family as an essential unit of capitalist reproduction in the wake of its alleged destabilization in the 1960s and ’70s. Lavery describes a different kind of familial recuperation: her focus is not the convergence of home and work that defines the prestige drama but the situation comedy’s formal imperative to restore the family’s heterosexual normalcy episode by episode, week after week.

Closures traces the sitcom from its origins in the mid-20th century through the finale of Bojack Horseman (2014–20) on January 31, 2020. In its earliest incarnations, the sitcom was almost exclusively focused on family life. Subsequent genre-defining shows like I Love Lucy (1951–57), All in the Family (1971–79), and The Cosby Show (1984–92) invented new hooks with which to narrate the interpersonal dramas of that life. They also portrayed everyday conflicts with levity, and if those conflicts were funny, they were so in a recognizable way: classic sitcoms tap into a time-honored comedic mode—ubiquitous from Twelfth Night to You’ve Got Mail—that finds resolution in a happy ending that restores some measure of social harmony. For the sitcom, however, comedic resolution poses a potential problem. Does closure lose its force when it happens over and over again, one week after the next? Not exactly, Lavery insists.

Bojack is an elegant choice with which to conclude the sitcom’s lifetime, not least because this cartoon for grown-ups about a washed-up former sitcom star is an irreverent elegy for the form itself—and, in many ways, an extreme extrapolation of that form’s relation to closure. The show picks up years after the success of the sitcom-within-a-sitcom Horsin’ Around. Depressed alcoholic Bojack is forced to confront his past abusive treatment of his former costar “family.” By the series’ conclusion, intimacy with family is no longer possible. Bojack is denied closure with regard to the dissolution of his relationships generally, and the viewer is denied narrative closure with regard to the conflicts that attend him. Rather than restoring the family to harmonious normalcy, as a sitcom like Horsin’ Around would, Bojack Horseman refuses the very premise of the happy sitcom family, as well as the demand for closure—narrative or otherwise.

In the classic sitcom, the familial bond is affirmed, but never decisively; each episode’s closure remains tentative, and in need of subsequent renewal. For Lavery, the sitcom thus indexes a fundamental instability in the structure of the family unit: “[D]espite its reputation as a normative model of heterosexual social reproduction, the sitcom in fact presents the heterosexual family neither as the inevitable point of departure for comic plot nor indeed its point of arrival.” Lavery points out that “the sitcom dwells in the present continuous, where family is always on the verge of disintegrating and always in the process of being repaired or reconstituted.” Not every episode, in other words, can end with a wedding.

The implications are queer. For Lavery, the sitcom is interesting because of its inherent incompletion, which points to the incompleteness of the social reproduction of heterosexuality. Episodic comedies about families require the introduction of queer external elements—a weird classmate, a competent butch maid—to sustain themselves. These added comic characters embody an anti-familial eccentricity that is necessary to propel the narrative into the next week’s script.

In Lavery’s reading, the sitcom’s heterosexual family is tellingly unstable in the regularity with which it disavows that eccentricity, and its queer potential generally. Sitcom families are often made up of people with little in common—siblings like Bart and Lisa Simpson aren’t exactly on the same wavelength—but these differences are absorbed and nullified by the organizing principle of the family. These families are also often blended or intergenerational—e.g., The Brady Bunch (1969–74), Full House (1987–95)—nontraditional even in the sitcom’s insistence on their everydayness. But the sitcom’s wacky family agglomerations nevertheless guard against more radical threats precisely by domesticating them. The Obama-era, “post-racial” Modern Family (2009–20), for example, manages its misogynistic, homophobic, and racist tropes by insisting on the middle-class normalcy of its gay and multiracial family life.

Lavery argues further that the social position of sitcom heterosexuals typically depends upon some recognition of a provisional transsexuality. “Cis” and “trans” are mutually determined categories of identification in her account. The heterosexuality of the sitcom family must admit the possibility of transsexuality, and this tension seemingly intensifies as the sitcom develops from its midcentury origins. For Lavery, this development is exemplified in the gradual subordination of the sitcom to the rom-com. Where the sitcom constitutes the heterosexual plot as incomplete and repetitive, the rom-com “must be brutally teleological or it is nothing.” If the sitcom is the genre of an interminably enjoined heterosexual collapse, in which the family is forever on the verge of disintegration, the rom-com drives toward a more ostensibly final resolution. Its horizon is the couple form: Ross and Rachel from Friends (1994–2004) must end up together, as will Pam and Jim; so too must Ben and Leslie of Parks and Recreation (2009–15), or Daphne and Niles of Frasier (1993–2004).

Closures works between psychoanalytic and formalist traditions to think about sexed embodiment and the production of identity in the sitcom. Its close readings operate in tandem with theoretical claims about the social and psychic production of sexuality. There is often real pleasure in those readings—whether of the Hollywoodification of the Addams Family; Steve Urkel as “the identified patient” of psychoanalysis, the family member who expresses the family’s inner dysfunction; or the bodily abjection of Dwight Schrute. And it is testimony to Lavery’s agility as a critic that she sustains her lovely readings even while deriving them from sometimes dense theoretical arguments.

Closures covers a lot of ground in less than 100 pages, from Hegelian dialectics to Rick and Morty (2013– ). But underlying the book’s diversity, and its analysis of the sitcom specifically, is Lavery’s theoretical investment in contradiction as a structuring dynamic of texts as well as of social life itself. In this, Lavery joins Marxist feminists for whom heterosexuality is the fundamental contradiction of social reproduction. One way or another, such feminists tend to ask, why does the heterosexual woman find an arrangement of structural inequity desirable? And significantly, and with real originality, Lavery reads heterosexual and trans femininity as intertwined, historical contradictions. “When the trans woman writes herself into the world, she does so under the sign of a heterosexuality whose contradictions have been intensified to the point of crisis,” she writes. “She is the scapegoat for heterosexuality but she is also its apotheosis, the ne plus ultra of heterosexuality, into whose event horizon heterosexuality is pulled, spaghettified.” The sitcom is contradictory in just this spirit, structurally dependent on the queer figures it must also cast out.

In her introduction, Lavery acknowledges the influence of recent work by trans-feminist and Marxist-feminist scholars and theorists such as Jules Gill-Peterson, Emma Heaney, Amy De’Ath, and Kay Gabriel. These influences are clear throughout Closures, particularly in the later sections on trans femininity and the telos of the rom-com. And although Lavery claims that the book is not a theoretical or political intervention but rather the formal assessment of a genre, Closures feels richly productive. The book is a timely demonstration of the ways that theoretically rigorous close reading can open up cultural objects in new ways.

Closures doesn’t make an explicit political intervention beyond its critique of the sitcom, even if it appears poised to do so. That Lavery stops just short of producing a polemic about the family generally, rather than her chosen genre, is indeed curious. There is nothing particularly reticent about her literary interpretations, which tend to move with a zany, breakneck speed. But why stop there? Lavery’s other critical work produces explicit political claims via close literary analysis. Closures nearly does make a broader historical argument, I think, about the relationships among transformations in the family form, the sitcom as a changing genre, and gender transition and transsexuality in the later 20th century. But Lavery doesn’t really spell those relationships out. And her playful and sometimes labyrinthine prose style, it’s worth noting, risks an argumentative slipperiness that at times abjures explication of critical problems. Perhaps it is unfair to ask the book to do something other than what it professes to do, but it would seem that Lavery does have more to say about transition and the family form historically.

Regardless, Closures demonstrates what a masterful literary critic can do with the flimsy and the abject, as the book brings high theory to bear—delightfully, speculatively—on the likes of Mork & Mindy (1978–82) and New Girl (2011–18). Lavery’s work makes the case not only for the sitcom’s queer formal properties but also for the practice of close reading itself. Pam’s timid and conventional “motel art” may be exactly that, but this does not mean it has nothing to tell us. Like the sitcom, and like the heterosexual family, it opens itself to a transformative queer critique. Lavery points the way, proving beyond a doubt that the pleasures of criticism and bad TV need not be at odds.

LARB Contributor

Isabel Bartholomew is a PhD student in English and gender and sexuality studies at the University of California, Irvine. She studies reproductive labor, the politics of the family, and American popular culture since the late 19th century.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Gender Criticism Versus Gender Abolition: On Three Recent Books About Gender

Grace Lavery reviews Julie Bindel’s “Feminism for Women: The Real Tribute to Liberation,” Helen Joyce’s “Trans: When Ideology Meets Reality,” and...

Family No Longer Sustains: On Michael Szalay’s “Second Lives”

Olivia Stowell reviews Michael Szalay’s “Second Lives: Black-Market Melodramas & the Reinvention of Television.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!