Truths Too Terrible: On Arthur Schnitzler and Franz Kafka

LARB presents an excerpt from Adam Kirsch’s “The Blessing and the Curse: The Jewish People and Their Books in the Twentieth Century.”

LARB PRESENTS AN EXCERPT from Adam Kirsch’s The Blessing and the Curse: The Jewish People and Their Books in the Twentieth Century, out this week from W. W. Norton.

¤

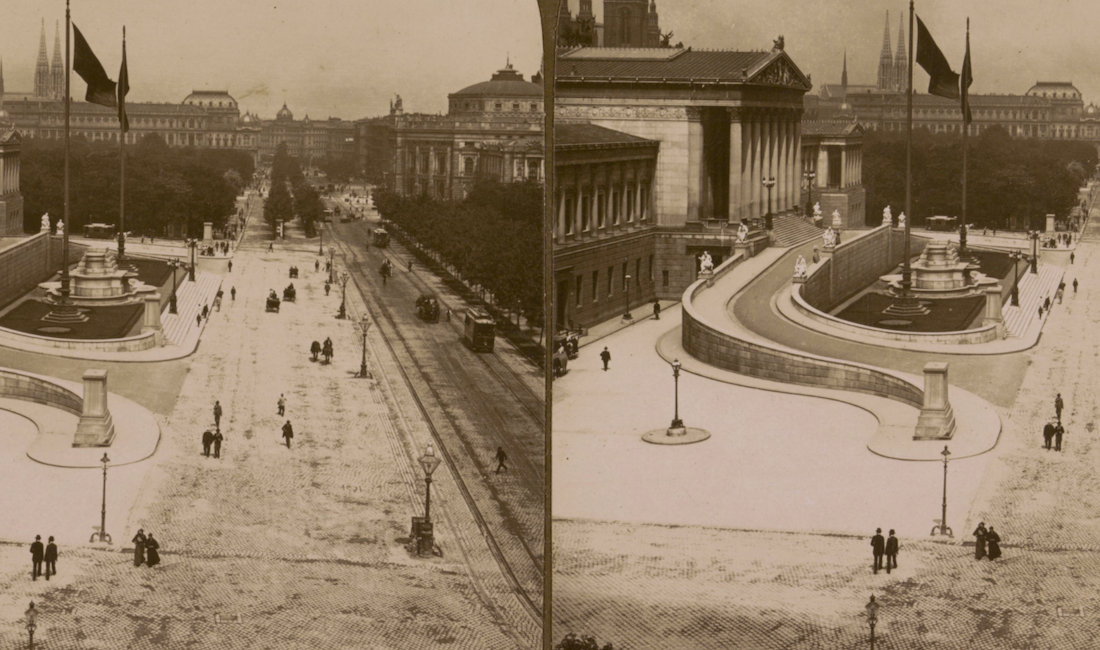

Vienna in the years before World War I was one of the golden ages of Jewish history. Over the preceding half-century, Jews from Austria’s Polish and Ukrainian territories, freed from old residential restrictions, flocked to the capital’s economic opportunities. In the 1850s, there were only 2,500 Jews in Vienna; by 1900, there were 150,000, almost 10 percent of the city’s population. And while most of them were poor or working class, the Jewish bourgeoisie was prosperous and open-minded enough to serve as the main patrons of the city’s cultural and intellectual life. Looking back on this period in his memoir The World of Yesterday, Stefan Zweig writes:

[T]he part played by the Jewish bourgeoisie in Viennese culture, through the aid and patronage it offered, was immeasurable. They were the real public, they filled seats at the theater and in concert halls, they bought books and pictures, visited exhibitions, championed and encouraged new trends everywhere with minds that were more flexible, less weighed down by tradition.

During these years, Arthur Schnitzler was one of Vienna’s most prominent Jewish writers. Trained as a doctor, he had given up medicine to pursue a career in literature — a choice that made perfect sense in a city that made a religion of the arts. Schnitzler became famous thanks to his 1897 play La Ronde — an unsparing look at the city’s erotic life, framed as a series of sexual encounters between partners from every social class, from prostitutes to noblemen. The play was too risqué to be performed publicly, but it became a best seller — and the source of much moralistic criticism, often framed in antisemitic terms.

In 1908, Schnitzler continued his investigation into Vienna’s sexual malaise with the novel The Road into the Open. At the center of the novel is a gentile character — indeed, an aristocrat, Georg von Wergenthin, who embarks on an affair with a young Catholic girl named Anna Rosner. Georg is a study in indecision, refusing to make serious commitments either to his musical career, which he engages in only amateurishly, or to Anna, whom he gets pregnant but refuses to marry.

But what gives The Road into the Open its enduring interest is not Schnitzler’s portrait of the sexual mores and spiritual drift of Viennese intellectuals. It is, rather, the novel’s sympathetic portraits of Georg’s Jewish friends, who are trying in various ways to come to terms with their anomalous place in an increasingly antisemitic society. For an aristocrat like Georg to have so many Jewish friends is a sign that, on an elite level at least, the barriers to social intercourse were declining. In these circles, a baron like Georg can socialize on equal terms with Jews like Else Ehrenberg — a music aficionado who cherishes a silent, unrequited love for him — or a man like Heinrich Bermann, a writer who proposes to collaborate with him on an opera.

For most of the Jewish characters in The Road into the Open, Jewishness is no longer a religious identity or even a cultural one. In all visible respects, they share the same values and lead the same lifestyle as their gentile neighbors. Yet this only makes the antisemitism they face harder to deal with, since no conceivable adaptation on their part can defuse it. The result is that relationships between Jews and gentiles, even when they approach intimacy, are never without self-consciousness. They may be able to dissimulate some of the time, Schnitzler suggests, but at bottom every Jew mistrusts every Christian, and every Christian has contempt for every Jew. As Heinrich Bermann demands of Georg,

Do you think there's a single Christian in the world, even taking the noblest, straightest and truest one you like, one single Christian who has not in some moment or other of spite, temper or rage, made at any rate mentally some contemptuous allusion to the Jewishness of even his best friend, his mistress or his wife, if they were Jews or of Jewish descent?

To Georg, on the other hand, it seems that Jews are simply too quick to take offense, too obsessed with their own Jewishness. “Why do they always begin to talk about it themselves?” Georg reflects. “Wherever he went, he only met Jews who were ashamed of being Jews, or the type who were proud of it and were frightened of people thinking they were ashamed of it.” He can’t understand why Jews lack the instinctive ease and self-confidence he enjoys as a titled aristocrat; as we might say today, he is blinded by his own privilege. Indeed, the very terms of his complaint show that Jews are in an impossible situation. Neither shame nor pride is the “right” reaction to their condition, but what is the alternative?

Through Georg’s eyes, we witness the agonizing attempts of Vienna’s young Jews to make sense of their place in a country that both is and is not their home. One of his acquaintances, the musician Leo Golowski, attends a Zionist Congress and is impressed by the seriousness and self-respect of the Jews who have embraced Zionism: “With these people, whom he saw at close quarters for the first time, the yearning for Palestine, he knew it for a fact, was no artificial pose. A genuine feeling was at work within them, a feeling that had never become extinguished and was now flaming up afresh under the stress of necessity.”

Leo’s sister, Therese, on the other hand, opts for the other great political movement of the age, socialism. She becomes a Social Democratic deputy to parliament and spends time in jail for insulting the emperor. But no one in the novel takes her quite seriously — partly because she is an elegant young woman, partly because the idea of a future socialist revolution seemed incredible, at least in 1908. Meanwhile, Doctor Stauber, another young Jewish politician, has to resign his seat in the face of the unrelenting antisemitic abuse that is showered on him every time he gets up to speak in Parliament. Party politics, Schnitzler suggests, is no cure for the Jewish problem.

In the end, it is left to Heinrich, Georg’s closest Jewish friend, to express the true hopelessness of the situation. Heinrich rejects Zionism because he rejects any form of group identity: “[H]e felt himself akin with no one, no, not with anyone in the whole world.” For Judaism, as for all religions, he has only contempt: “What does the faith of your father mean to you? A collection of customs which you have now ceased to observe and some of which seem as ridiculous and in as bad taste to you, as they do to me,” he tells Leo. Yet while he rejects positive forms of solidarity, Heinrich identifies himself completely with the Jews when it comes to feeling shame and embarrassment. “We have been egged on from our youth to look upon Jewish peculiarities as particularly grotesque or repulsive,” he explains to Georg. “I will not disguise it — if a Jew shows bad form in my presence, or behaves in a ridiculous manner, I have often so painful a sensation that I should like to sink into the earth.”

But this revulsion does not delude Heinrich into thinking that he could ever become a true Austrian, either. In Austria, he says to Georg’s shock, Jews are “in a foreign country, or […] in an enemy's country.” That is precisely why Jews are such good students of Austrian culture and society: after all, “the primary essential is to get to know one’s enemies as well as possible — both their good qualities and their bad.” Finally, Heinrich throws up his hands and declares that the problems of antisemitism and Jewish self-hatred will take at least a thousand years to solve:

In our time there won’t be any solution, that’s absolutely positive. No universal solution at any rate. It will rather be a case of a million different solutions. For it’s just a question which for the time being everyone has got to settle for himself as best he can. Everyone must manage to find an escape for himself out of his vexation or out of his despair or out of his loathing, to some place or other where he can breathe again in freedom. […] Everyone’s life simply depends on whether or not he finds his mental way out.

As it turned out, the Jews of Vienna didn’t have a thousand years to wait; they had exactly 30. In 1938, Nazi Germany would annex Austria, amid a fierce outburst of popular antisemitism. Over the next year, about two-thirds of the city’s Jewish population of 200,000 fled. The “mental way out” that Heinrich looked for was not nearly enough: of the Jews who remained in the city, all but 2,000 were exterminated in the Holocaust. By 1945, the Jewish population of Vienna had returned to the level of the 1850s; Jewish Vienna, it turned out, had lasted a little less than a century.

¤

For all his pessimism, Schnitzler couldn’t have imagined what the future had in store. Franz Kafka, on the other hand, would have seen it as a grim vindication of his own darkest intuitions. Kafka was 31 years old when he started The Trial in August 1914, just after the beginning of World War I; after six months he put the manuscript aside, and when he died — of tuberculosis, in 1924, at the age of just 40 — it was still incomplete. Kafka left instructions for his friend and literary executor, Max Brod, to destroy all of his unpublished work. But Brod, convinced of Kafka’s genius, refused to carry out his wishes. Instead, he edited The Trial into something like a coherent sequence and arranged for it to be published. The first edition came out in 1925 and attracted little attention, but in the 1930s Kafka’s reputation began to grow, and in the post–World War II era The Trial became one of the 20th century’s emblematic tales.

That story is so simple it can be summarized in a few sentences, yet so mysterious that countless pages have been devoted to analyzing it. Joseph K., an ordinary middle-class office worker, wakes up one morning to find that two men are waiting to arrest him. But they are not officers of any recognized court, and they never inform him what he is supposed to have done. All he is told is that he is now on trial, and the bulk of the novel consists of his encounters with various representatives of the legal system that has taken over his life — magistrates, guards, lawyers, even a chaplain.

The worst part is that no one seems to be able to explain the laws under which he is being tried, which are infinitely complex. All he can glean is that acquittal is seemingly impossible: “I know of no actual acquittals,” the painter Titorelli tells Joseph K. “Of course it’s possible that in the cases I’m familiar with no one was ever innocent. But doesn’t that seem unlikely? In all those cases not one single innocent person?” To which Joseph K. bitterly replies: “A single hangman could replace the entire court.” Indeed, that proves to be the case: at the end of the book, in an abrupt and terrifying scene, Joseph K. is seized by a pair of court-appointed executioners and slaughtered with knives — “like a dog,” as he exclaims with his dying breath.

The Trial is deliberately stripped of the kind of realistic local references that tether Schnitzler’s novel so closely to its time and place. While Kafka lived in Prague — one of the leading cities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and later the capital of the new state of Czechoslovakia — the city where Joseph K. lives contains no Prague place names or landmarks. The settings where the story unfolds are generically urban: a boarding house, a bank office, a church. Similarly, Joseph K. himself is deprived of a complete name, which might have given us a clear sense of his nationality. Certainly the word “Jew” never appears in The Trial, and it is entirely possible to read it without knowing or suspecting that Kafka was Jewish.

Yet Kafka was not far removed in time or space from the Jews of Schnitzler’s novel. Like them, he spent his whole life in a Jewish community frequently beset by popular antisemitism; and like them, he was not religiously observant. Kafka’s upbringing in an assimilated family left him with ambivalent feelings about Judaism, as he explained in a long letter to his father:

[Your Judaism] was too little to be handed on to the child; it all dribbled away while you were passing it on. In part, it was youthful memories that could not be passed on to others; in part, it was your dreaded personality. It was also impossible to make a child, over-acutely observant from sheer nervousness, understand that the few flimsy gestures you performed in the name of Judaism, and with an indifference in keeping with their flimsiness, could have any higher meaning.

Despite this legacy, as an adult Kafka took a serious interest in Jewish subjects, including Yiddish theater and Zionism. Toward the end of his life, he even began to study Hebrew in preparation for a possible emigration to Palestine. If figures like Schnitzler’s Heinrich Bermann were painfully aware of their Jewishness in every moment, how could it not have been equally important to Kafka, who resembles them in so many ways — above all, in his extreme self-consciousness?

Indeed, one way to read The Trial is as an oblique fable about the same Jewish condition that Schnitzler treated in a direct, realistic mode. “Someone must have slandered Joseph K.,” says the book’s first sentence, “for one morning, without having done anything wrong, he was arrested.” This was the very condition in which the assimilated Jews of Europe found themselves — the targets of hatred and suspicion that were based not on their actual character or actions but on myth and prejudice. These Jews were constantly on trial in the court of gentile opinion — and like Joseph K., they were doomed to lose their case, because they faced hostile judges who operated according to indefinable rules.

At first, Joseph K. believes that he can rise above this hostility, the way that many assimilated Jews believed that antisemitism was a mere nuisance, not to be taken too seriously. In an early scene, he makes a long, self-righteous speech to the crowd at his first court hearing: “I’m completely detached from this whole affair, so I can judge it calmly,” he assures them. He claims to be interested only in abstract fairness: “What has happened to me is merely a single case and as such of no particular consequence […], but it is typical of the proceedings being brought against many people. I speak for them, not for myself.” But this lofty rhetoric only annoys the crowd, and makes the magistrates still more biased against him.

The kind of hostility Joseph K. is dealing with, he learns over the course of the novel, cannot be sidestepped or dismissed. It is serious, irrational, and, in the end, lethal. Nothing Joseph K. does to prove his innocence will be of any use; he is on trial not for something he has done, but simply because he has been singled out. In all these ways, his situation reflects that of a Jew trying to fit into an antisemitic society.

And the ending of The Trial can be read as a foreboding of the fate of Europe’s Jews, who went in a shockingly short time from respectable citizens to pariahs to victims of slaughter. In the novel’s last scene, what strikes Joseph K. as he faces death at the hands of the court’s executioners is the nearness and indifference of bystanders. He spies a person leaning out of a window and asks: “Who was it? A friend? A good person? Someone who cared? Someone who wanted to help? Was it just one person? Was it everyone?” These are exactly the questions that, less than 30 years after Kafka wrote The Trial, his own friends and family members might have asked about the gentile neighbors who watched as they were deported to Auschwitz.

The key to the unsettling power of The Trial, however, and to its global readership and influence, is that, unlike Schnitzler, Kafka did not write about these experiences as Jewish experiences. Rather, he allowed the Jewishness of The Trial, and of much of his other work, to remain a kind of optical illusion, visible only to those readers who were equipped to recognize it. Indeed, part of what creates the atmosphere we have come to call Kafkaesque is precisely this sense that there are reasons and motives at work in his writing that he does not name.

It would be wrong to say that The Trial is “really” about antisemitism, as if the work’s many other theological and political dimensions were unreal. But it was his experience of being a modern European Jew at a time of profound Jewish crisis that gave Kafka such an immediate experience of the alienation and isolation, the helplessness and guilt, that would become central to the experience of so many people in the 20th century. Jewishness, he suggests, is not a unique fate but an extreme one, which equips the writer — at least, when the writer is Kafka — to see truths too terrible for most people to recognize until it is too late.

¤

LARB Contributor

Adam Kirsch is the author of several books of poetry and criticism, including Who Wants to Be a Jewish Writer? and The People and the Books: Eighteen Classics of Jewish Literature. His most recent volume is The Blessing and the Curse: The Jewish People and Their Books in the Twentieth Century. A 2016 Guggenheim Fellow, Kirsch is an editor at the Wall Street Journal’s Weekend Review section and has written for publications including The New Yorker and Tablet. He lives in New York. (Photograph by Miranda Sita.)

LARB Staff Recommendations

Zones of Independence: A Conversation with Adam Kirsch

Morten Høi Jensen asks Adam Kirsch about his new book, “Who Wants to Be a Jewish Writer?”

Midnight Madness: Franz Kafka’s “Investigations of a Dog: And Other Creatures”

“Investigations of a Dog: And Other Creatures” offers a glimpse into Franz Kafka’s crazed late-night writing sessions.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!