Midnight Madness: Franz Kafka’s “Investigations of a Dog: And Other Creatures”

“Investigations of a Dog: And Other Creatures” offers a glimpse into Franz Kafka’s crazed late-night writing sessions.

By Nathan Scott McNamaraJune 10, 2017

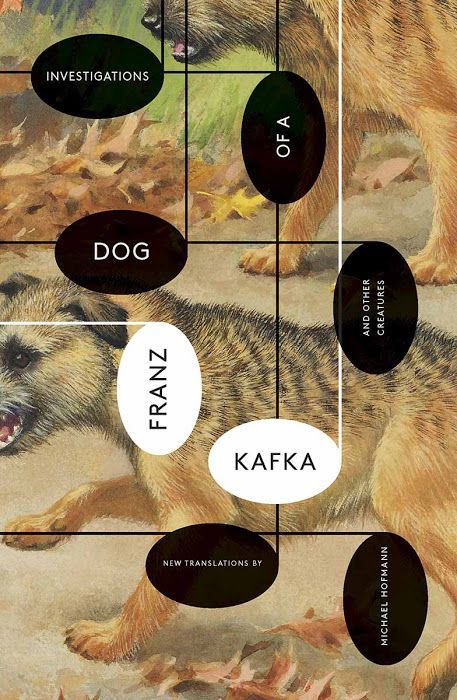

Investigations of a Dog by Franz Kafka. New Directions. 244 pages.

FRANZ KAFKA NEVER left home. Outside of a year in Berlin and a stay at a sanatorium near Vienna before his death, he lived in the same part of Prague — mostly at his parent’s house — for all 40 years of his life, worked as a clerk at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute, and never married.

Kafka’s inertia, a sort of isolation from the larger world, was central to his obsessive and anxiety-fueled stories. He defended his solitude and curated his deranged state. He even wrote in the middle of the night, while the rest of Prague slept. In 1912, in a letter to Felice Bauer, Kafka explained that each day he was at the office from 8:00 a.m. to 2:30 p.m., then ate lunch, then slept (“usually only attempts…”) until 7:30 p.m. Then after 10 minutes of naked exercise in front of the open window, he usually took an hour-long walk with his friend Max Brod, and finally had dinner with his family. “Then at 10:30 (but often not till 11:30) I sit down to write,” Kafka said,

and I go on, depending on my strength, inclination and luck, until 1, 2, or 3 o’clock, once even until 6 in the morning. Then again exercises, as above, but of course avoiding all exertions, a wash, and then, usually with a slight pain in my heart and twitching stomach muscles, to bed.

This was not a comfortable or happy way of being. As Michael Hofmann writes in the introduction to his translation of Investigations of a Dog: And Other Creatures, “[Kafka] devised for himself a life that was largely disagreeable, inflexible and inescapable, and tried to make it productive.”

This New Directions release of Investigations of a Dog provides an opportunity to reconsider many of Kafka’s greatest stories in a new book, with beautiful cover design, and to reexamine how a brilliant mind performed under spiritually backbreaking circumstances.

Nighttime offered Kafka privacy from the world, and access to uninterrupted, delirious concentration. In “A Young and Ambitious Student” (titled, like many of these stories, after Kafka’s death by Max Brod), Kafka writes about a boy who, against his parents’ — “poor tradespeople in the provinces” — knowledge and at their expense, abandons everything in his life to study horses. He believes he can train horses in quasi-human thinking and feeling, and he does his work at night. Kafka writes,

In his view, the merest break in the animal’s concentration would do irreparable damage to the project, and at night he could be reasonably safe from such a thing. The sensitivity that comes over man and beast both waking and working at night was an integral feature of his plan.

The almost four-hour stretch of darkness and silence that Kafka had before him each night offered him the means to write some of the greatest micro-fiction of all time. Twenty-nine of the 42 stories in Investigations of a Dog are only one or two pages, and most of them are stunning. In “The Vulture,” a man narrates his experience of being picked apart by a giant bird. A passerby stops and asks the man why he doesn’t fight the bird off; he tried, the dying man says, but “a beast like that has a lot of strength in him.” Though only half a page long, the story is slow and patient — the vulture taking its time to eat its prey. The passerby remarks that a single bullet would solve this situation, and the dying man asks if he would oblige. “Willingly,” the passerby says. “I just have to go home and get my gun. Can you wait another half an hour?” The narrator says, “I don’t know,” and goes stiff with pain. We realize he’s actually thinking about whether or not he can survive that long, and if the journey for the gun is worth it. He says, “Well, will you try anyway?”

The unsettling effect of this story comes, in part, from its combination of horror and comedy. And as the reader starts to laugh, Kafka takes the story through a very dark final turn. “Like a javelin thrower, he thrust his beak through my mouth deep into me,” the narrator says. “As I fell back, I could feel a sense of deliverance as he wallowed and drowned in the blood that now filled all my vessels and burst its banks.”

Many of Kafka’s very short stories were creations of single nocturnal sessions, and they accomplish the paradoxical blending of sustained anxiety and lightning bolt brevity. In a nightmarish spirit, they heighten the sense of an infinite and paralyzing struggle. The darkness of the humor doesn’t come from the threat of death; it comes from the overwhelming idea that life will continue. David Foster Wallace once wrote that the central joke in Kafka’s work was that “[t]he horrific struggle to establish a human self results in a self whose humanity is inseparable from that horrific struggle. That our endless and impossible journey toward home is in fact our home.”

In “Poseidon,” for example, the Greek God of water sits at his desk working. It turns out that controlling the oceans and seas mostly consists of unending bureaucratic tasks. “One couldn’t say that the work made him happy,” Kafka writes. “He only did it because it was his to do.” The story ends with Poseidon thinking that if he does this for the rest of his life, he might have a moment right before he dies when he can go on a cruise somewhere.

In one of Kafka’s most haunting paragraph-length stories, “Night” (again titled by Brod), he imagines the middle of the night as an occasion for sinister activity. “All around, people are asleep. A little bit of playacting on their part,” Kafka writes. He says that in reality, these people are gathered on “wild terrain, in a camp in the open, a vast number of people, an army, a tribe, under a cold heaven on a cold earth.” We don’t learn what this army is up to, but it certainly feels evil. “[Y]ou, you’re keeping watch, you’re one of the sentries,” Kafka writes, calling out to his fellow insomniacs. “[Y]ou communicate with the next man by waving a burning stick from the driftwood fire beside you. Why do you keep watch? Someone has to keep watch, they say. Someone must be there —”

In Kafka’s longer stories, we still encounter the virtues of his mad approach, but also sometimes its logistical or psychological limits. Take “The Village Schoolmaster,” a wild story about a teacher who encounters a monstrously large rodent (a mole), and dedicates his life to proving its existence. The story is steeped in the absurdity of personal convictions, as well as the terror of self-doubt. The teacher becomes convinced that the narrator of the story is trying to steal his research, and lashes out by angry letter. Empathizing with him, the narrator says, “His behavior was not caused by greed, or at least not greed alone; it was more the irritation that his great efforts and their total lack of success had caused in him.”

In a December 1914 diary entry, Kafka writes:

Yesterday wrote “The village schoolmaster” almost without knowing it, but was afraid to go on writing later than a quarter to two; the fear was well founded, I slept hardly at all, merely suffered through perhaps three short dreams and was then in the office in the condition one would expect.

The story was never finished. In another diary entry a year later, Kafka says he abandoned it. Hofmann writes that Kafka’s production was “hectic, excessive, and fiercely doubted.” Most of his books he left unfinished.

The title story from this collection very much demonstrates the occasional bounds of Kafka’s circumstances, or maybe just our over-eagerness to look for genius in everything he did. (In a final letter to Brod, Kafka asked him to burn everything he had written. Most of what’s now considered Kafka’s oeuvre was unpublished in his lifetime.) “Investigations of a Dog,” nearly 40 pages long, is told from a dog’s perspective. In an exhaustively tedious manner, this animal recounts episodes from his past and attempts to use rational methods to resolve the basic questions of his own existence. “Withdrawn, solitary, entirely taken up with my small, hopeless but — to me — indispensable inquiries,” the dog says, “that’s how I live.”

Kafka’s iconic creature story, “The Metamorphosis” (not included in this collection), uses the frightening experience of transformation, pairing lofty existential questions with visceral realities — Gregor Samsa scrambling to learn how to move his new body, how to communicate with his family, what to do about missing work. Reflecting on how to live after turning into a cockroach is a frightening circumstance. Reflecting on being a dog after a lifetime of being a dog is mostly tiresome, and feels like chasing one’s own tail.

One of the most fascinating elements of Investigations of a Dog: And Other Creatures is considering the sketches of some of Kafka’s longer works. The two-page story “It Was One Summer…” reads like a miniature version of The Trial. In the story, a narrator and his sister are confronted for the close-to-nonexistent cause that the sister tapped a gatepost while walking past. “[The townspeople] said that not only my sister but I too as her brother stood to be accused,” Kafka writes. The sister disappears to put on a nicer outfit. Men arrive on horseback and ask where she went, and the narrator says she’ll be back later. “The answer was received almost with indifference; what seemed to matter was that I had been found.” The final image of the story is a room with dark gray bare walls, and in the middle “something that looked half-pallet, half operating table.”

Kafka turned his ideas over again and again, and while he didn’t mean for many of these stories to be published, the obsessive return, and their sketch-like qualities, doesn’t diminish their effect. “Our laws are unfortunately not widely known,” Kafka writes in another Trial-esque story. “They are the secret of the small groups of nobles who govern us. We are convinced that these old laws are scrupulously observed, but it remains an extremely tormenting thing to be governed by laws one does not know about.”

Wrapped up in Kafka’s genius is his mental and physical frailty, his provinciality, and his single-minded fixations. Rather than the sense of a Herculean writer, we’re drawn in by the sense of a man who’s being destroyed by the grueling realities of modern living. Kafka didn’t have the time to write, but he still did. A writer and full-fledged participant in industrialized society, Kafka wasn’t healthy, and he died of tuberculosis at 40.

“It is easy to recognize a concentration in me of all my forces on writing,” Kafka wrote in his diary.

When it became clear in my organism that writing was the most productive direction for my being to take, everything rushed in that direction and left empty all those abilities which were directed towards the joys of sex, eating, drinking, philosophical reflection, and above all music. I atrophied in all these directions. This was necessary because the totality of my strengths was so slight that only collectively could they even halfway serve the purpose of my writing.

Kafka’s stories demanded exhaustion and sacrifice. To aspiring writers, in particular, one of the important lessons of Kafka’s life and work is maybe you don’t really want this. But if you do, forget excuses. Write in the middle of the night.

¤

LARB Contributor

Nathan Scott McNamara also contributes at Literary Hub, the Atlantic, the Millions, the Washington Post, Electric Literature, and more. Follow him at @nathansmcnamara, or read more at nathanscottmcnamara.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Lesser-Known Kafkas

Mark Harman on Reiner Stach's "Kafka: The Early Years."

Goodbye, Eastern Europe!

Jacob Mikanowski shares a few lessons about a vanishing Eastern Europe.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!