The Immensity of Brevity: On Ben Okri’s “Prayer for the Living”

Babi Oloko is enchanted by "Prayer for the Living," the new collection of short stories by Ben Okri.

By Babi OlokoFebruary 2, 2021

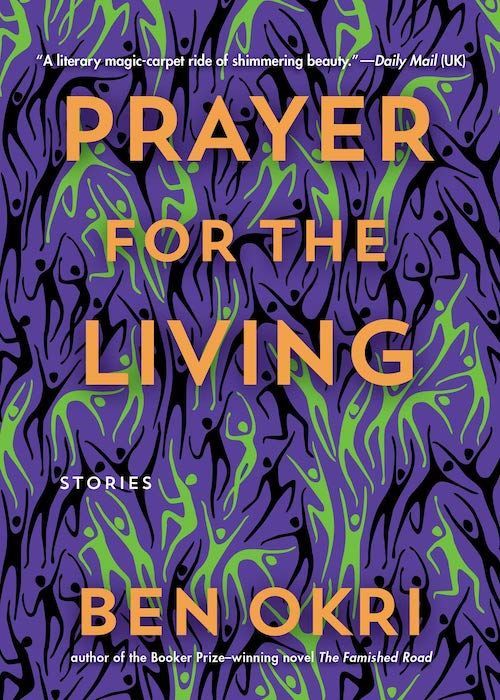

Prayer for the Living by Ben Okri. Akashic Books. 216 pages.

THE FIRST SHORT STORY in Ben Okri’s Prayer for the Living, “Boko Haram (1),” opens with a tense scene in a Nigerian marketplace on a hot day. A young boy speaks with his father and a few other men before beginning a journey to the center of the market that lasts only a few lines but feels like a lifetime. As the boy walks, he is called out to by the vendors he knows — this place is familiar to him. He walks past fish and cloth merchants as the sun shines innocuously above. One moment, the boy is standing still, waiting. In the next moment, the world explodes as the bomb attached to the boy’s chest detonates, completely obliterating everyone and everything around it. All of this happens in the span of two sentences.

“Boko Haram (1)” is less than a page long, yet it is haunting. Okri is a master in knowing what is better left unsaid. He trusts the minds and imaginations of his readers to fill in the absences. Okri does not name the boy or his feelings in the tense moment before he and the world around him are ripped to shreds. He does not describe the rubble and the shock of this calamity. Yet the reader can feel it all poignantly.

Though Okri’s stories rarely surpass a handful of pages, their brevity does not make Prayer for the Living a quick read. I found myself compelled to go over the same pages and stories multiple times. Within the shortness of Okri’s texts lie their multitudes; each word chosen is vital. While the text is often enigmatic, it leaves just enough room for a reader to untangle the webs Okri weaves. Okri’s style often drifts toward the poetic. He repeats structures and themes, creating cohesion and reinforcing important messages across his stories which can seem disparate at face value but are often intertwined in meaning.

Okri rapidly takes his readers from world to world. After “Boko Haram (1),” we are at a house within a house on London’s Baker Street where a young girl’s dollhouse starts to bustle with unnatural activity. Sudden tragedy befalls her family. Later, Okri takes us to the ghetto by Badagry Road, where three boys and their father attempt to push their stalled Peugeot down the road. Rosicrucians study a cursed mirror. A jujuman disappears. A warrior rides an ornery donkey. By the time readers have settled into one story, the next one has already begun; however, these transitions never feel jarring. I found myself effortlessly swept up in Okri’s different worlds.

Reading Prayer for the Living was a corporal experience for me, the likes of which I have not had since I was a child reading fantasy books with mystical worlds. My heart sped up, my stomach dropped, I gasped, I laughed, I closed the book and gazed out the window for a few minutes then came back and opened the book again. Prayer for the Living took me on an emotional odyssey: it is pensive, humorous, and somber, often at the same time. Okri ensures his readers will become deeply invested in his stories, writing so intimately that the lines between reader and character become blurred. As I turned from page to page, I felt like I entered each of the tales. At one point, I was a disheartened king on a quest to learn the truth of life. I became a detective trying to solve a murder that occurs in multiple universes at once. I then morphed into a young woman determined to communicate with the spirit of the lake. I moved from London to Machu Picchu to New York to Istanbul and back again. I went from old to young, Black to white, male to female, lord to peasant. Each of these transitions happened effortlessly and swiftly, allowing me to experience the multiplicity of existence as I stepped into a new life every few pages.

Coming out of 2020, a year marked by fear, setbacks, and stagnancy, it was particularly refreshing to disappear into the new possibilities Okri vividly creates. Prayer for the Living is not all escapism — Okri makes several political and cultural references, writing on present-day immigration in Europe and terrorism in Nigeria, as well as touching upon the general themes of colonialization, racism, and cultural erasure. He addresses these topics delicately, without inserting his own opinions or prodding the reader too overtly.

Prayer for the Living is what would happen if Schrödinger’s Cat and the Butterfly Effect got together and made a limitless, mystifying literary baby. As the stories shift from one perspective to another, Okri’s sage voice remains constant. He reminds his readers that nothing in life happens in a vacuum, and each of its endless possibilities has the potential to create endless reactions. Despite the stark differences in the plots and setting of his short stories, Okri highlights the interconnectedness of existence in his writing. No matter how different each story is in context or story line, Prayer for the Living is not simply a collection of different tales, it is a deliberate assemblage of universal truths that explores what it means to seek and to live.

The short stories are suspended somewhere between the worlds of fantasy and mundanity. They are rooted in ordinary events and imbued with references to familiar cities, restaurants, and locations, making them feel tangible. Okri further grounds his text in palpability by making numerous artistic references, alluding to white male “masters” such as William Butler Yeats, Arthur Miller, Gustav Mahler, and Anton Chekhov. Despite the tangibility of Okri’s writing, each story has a curious, often magical element to it, perhaps due to the content examined in his stories. He grapples with complex subjects such as the multiverse, the unseen world, the nature of truth, and the perils of desire. He does this all deftly and unpretentiously, letting readers draw their own conclusions and answers to the thoughtful questions posed.

In “Don Ki-Otah and the Ambiguity of Reading,” the protagonist describes the sage warrior originally known as Don Quixote who speaks in an unfamiliar way (Okri himself makes a cameo as a character in this story):

He made words sound more than they are. Other people say words and they mean less. He made words feel like more. He made your hairs stand on end when he spoke. […] With a few syllables he could induce madness. His speech rocked the back of my skull.

Just like Don-Ki Otah the warrior, Okri makes words sound like more than they are. His stories convey provocative, skull-rocking messages in the span of a few pages. There is something quite rare about the way Okri is able to so thoroughly entrance a reader in such a short word count. Each word chosen in Prayer for the Living is infinite in impact, conveying meanings that transcend mere definitions. When the shopkeeper questions the way Don Ki-Otah reads, Don Ki-Otah answers as Okri might: “[R]eading is about understanding that which cannot be understood, which the words merely hint at.”

¤

Babi Oloko studies race, contemporary art, and social theory. She lives and writes in the Northeast.

LARB Contributor

Babi Oloko hails from New Jersey and received her BA in history and literature as well as art history from Harvard University in December 2021. She writes art reviews, personal essays, and fiction for various digital publications, and hopes to write a fantasy book centering Black voices.

LARB Staff Recommendations

African Literature and Digital Culture

The digital impulses of African creativity have fundamentally altered literary culture.

The Persisting Relevance of Walter Rodney’s “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa”

Walter Rodney’s "How Europe Underdeveloped Africa" still reads cogently after almost 50 years.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!