That Glittering Southern Light

A new collection of stories explores the global contrast between North and South.

By Gerri KimberJanuary 12, 2020

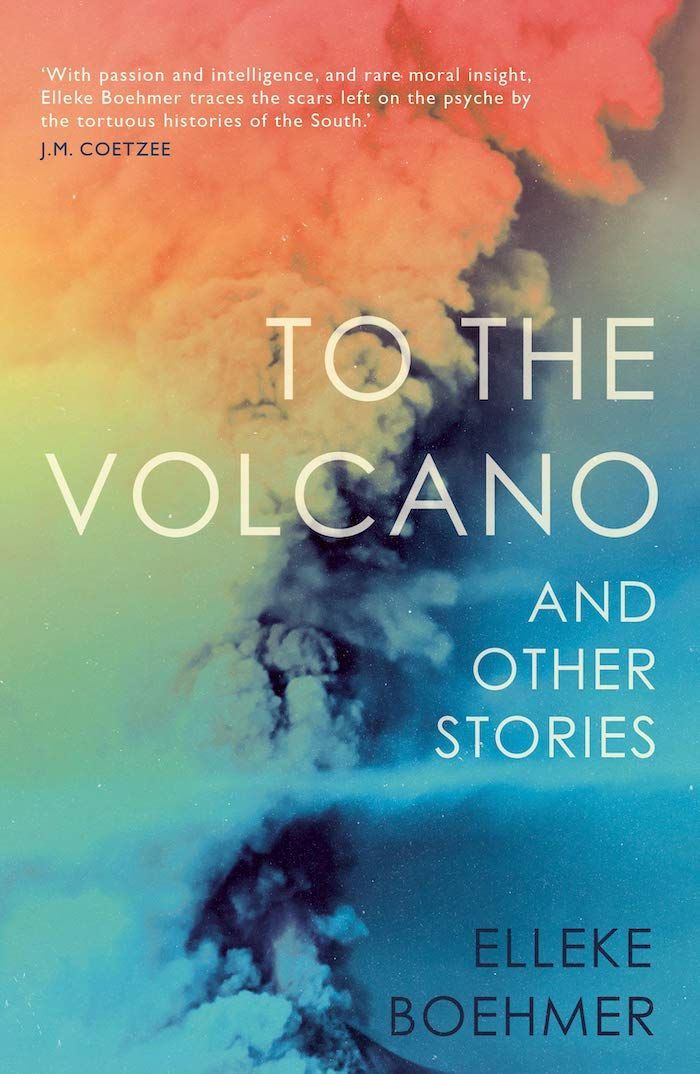

To the Volcano and Other Stories by Elleke Boehmer. Myriad Editions. 224 pages.

I’LL NEVER FORGET the first time I woke up in New Zealand, having arrived late at night from the other side of the world, beyond exhausted and unable to focus on anything except getting to my hotel room and crawling into bed. I had traveled widely but had never before crossed the International Date Line, or indeed the equator. So, on that first morning, I was unprepared for what happened when I drew back the curtains: an assault of light such as I had never before experienced. Once outside, I found that I couldn’t see properly unless I had sunglasses on, such was the light’s intensity. I was meeting a friend for coffee in downtown Wellington, and when I told him about my experience, he laughed and said, “Yes, of course! This is your first experience of southern light. I expect your poor old Northern European eyes will adjust eventually.” But they never did, and despite many more trips to New Zealand over the years, they never have.

According to New Zealand historian Jock Phillips, the Māori word for the country, “Aotearoa” — usually translated as “land of the long white cloud” — can also be translated as “long bright world” or “land of abiding day.” New Zealand’s most iconic author, Katherine Mansfield, who spent half her short life in Europe away from that light, remembered it vividly in her short story “At the Bay,” conjuring up memories of her childhood holidays by the sea: “[T]he leaping, glittering sea was so bright it made one’s eyes ache to look at it.”

Born and raised in Durban, South Africa, Elleke Boehmer also knows a thing or two about southern light. To the Volcano and Other Stories is her second collection of stories (she has also written five novels), and southern light — “southness” in general — is evoked in a number of them, to magnificent effect. The collection offers a variety of geographical settings, from South Africa to Southern Australia to South America. Most of the stories evoke a strong sense of place through characterization, landscape, language, and history — and, of course, through the quality of the light. By the end of the book, the world seems somehow smaller and more connected; Boehmer has taken her readers on an international journey of discovery, depicting characters of numerous nationalities, all with vivid personal stories to tell.

The title story offers a Forster-esque transformative journey undertaken by a group of mainly white academics, in this case not to a mysterious cave complex but rather to the crater of an extinct volcano in southern Africa. As in A Passage to India, the dark consequences of this sojourn change the lives of several of the characters. The “southness” of the story is emphasized from the start: we are told in the very first line that it is a “hot winter’s day.”

The university’s communications officer, Refile Masimong, is not an academic staff member or a student, and therefore not technically permitted to take the trip to the crater. However, she is “allowed” to go by lecturer Bob Savage, a cultural critic and “one-time Shakespearean, who now worked on celebrity icons like Monroe, Guevara, and logos of global interest, the Apple apple, for example,” so that she can write a report about the trip for the university newsletter. Refile knows the crater from her childhood; she understands why people call it “bewitched” and “powerful”: “Growing up, we never went to the volcano. It was zwifho, so our parents forbade it.” Boehmer doesn’t explain the word zwifho (which means a sacred natural site), but its use adds a note of verisimilitude amid the posturings of the white European academics.

Inside the volcano, chaos reigns: “Three parties went into the crater, and four returned, in different groupings from those that went in. […] All brought different stories. […] But everyone spoke of a weird other world, iridescent green, windless, sweltering, silent[.]” The intense light makes it hard to see, especially with the reflection of “the glittering light coming off the water.” Elsewhere, the light is described as a “white late-afternoon light,” while inside the crater the plants are depicted as vividly bright in color, a “radioactive green.”

Bob Savage gets left behind, and Refile climbs back into the crater to find him. He is eventually discovered, horribly sunburnt, asleep by some willows. As Refile escorts him out, he talks strangely of having “had a dream and a most rare vision, lady. And I would sing it to you, for you were in it.” Once back home, he finds himself consumed by a psychological fire that will not be satiated: “There were no words for this fever that possessed him, this great heat coursing through his body.” This all-consuming passion is directed toward Refile, with dire consequences. As she tells her friend Tex: “Something crept into his head that day he slept in the crater and it changed his life. He gave way to it, he let it change him.” Bob has opened himself up to zwifho, a force more powerful than the shallow constructs of his cultural criticism. Refile has grown up fearing this force, avoiding it, respecting its power, while the white immigrants to the land have not.

In another story, “The Child in the Photograph,” Luanda, a young black Oxford undergraduate from South Africa, finds that she cannot reconcile herself to the falsity of her new European life. She relies on laughter to get her out of uncomfortable situations, “laughing when they stumble on her name, laughing when they ask about her course and then forget and ask again, laughing, laughing, till the other students start calling her Laughing Luanda. Laughing, she asks them to stop.” Boehmer contrasts the cold, ancient stones of Oxford’s buildings with the vivid red sand of Luanda’s homeland:

She could not have dreamed up the pure coldness that rises from the stone and instantly chills her hand when she touches it. That anything could be so cold! She could not have imagined the cold dark shadows that wait in the corners of the stone and never shift.

This coldness affects her body: beneath her bright cotton dresses, she wears polo neck jumpers and long johns, creating an outer dichotomy that is gradually replicated in her increasingly troubled mind. Even the hairdressers don’t know what to do with her African hair, forcing her to go “out of town, two bus rides away, close to the industrial area,” away from the cold stone spires of the Oxford colleges. Eventually, even the sound of her laughter is extinguished by those cold stone walls. In the end, it is the child in the photograph on her bookcase — Nana, the little girl she has told everyone is her sister — who eventually forces her to make a life-changing decision, one that will see her laughter return.

The story “South, North” offers a compelling contrast between the dull, wet grayness of Europe and the warm, bright light of southern climes. Young Australian student Lise has backpacked her way to Paris to walk the streets made famous by her favorite author, Émile Zola. The light is pale, and the city seems constantly veiled in a light drizzle. “At home it barely ever rains,” Lise observes. Her hometown is in the middle of a desert, where even at night “[t]he ice-blue evening light [floats] over the southern horizon like a spaceship.” It’s the memory of that ice-blue light, following a frightening encounter on a Paris street, that leads to an epiphanic moment of self-discovery — about the meaning of “southness,” about home.

Other stories in the collection treat the process of growing old, the difficulties surrounding parenthood, and the pain of separation and unrequited love. Boehmer’s book is a gift of discovery for us all, whether we come from the South or the North, a reminder of the transformative power of acceptance — acceptance of cultural and geographical differences, and, most of all, acceptance of our roots, wherever they may be. Boehmer’s own roots are clearly in the South Africa of her childhood, and that glittering southern light.

¤

LARB Contributor

Gerri Kimber is a visiting professor at the University of Northampton, UK, and is the author/editor of 30 books on Katherine Mansfield. She is a reviewer for the TLS, has recently written her first YA fantasy novel, and is determined to secure a literary agent against all the odds.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Sunrise Over Maafa: On Edwidge Danticat’s “Everything Inside: Stories”

Joanie Conwell looks at “Everything Inside” by Edwidge Danticat.

The Persisting Relevance of Walter Rodney’s “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa”

Walter Rodney’s "How Europe Underdeveloped Africa" still reads cogently after almost 50 years.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!