Echoes of the Original: On the Task of Translating Maria Schneider

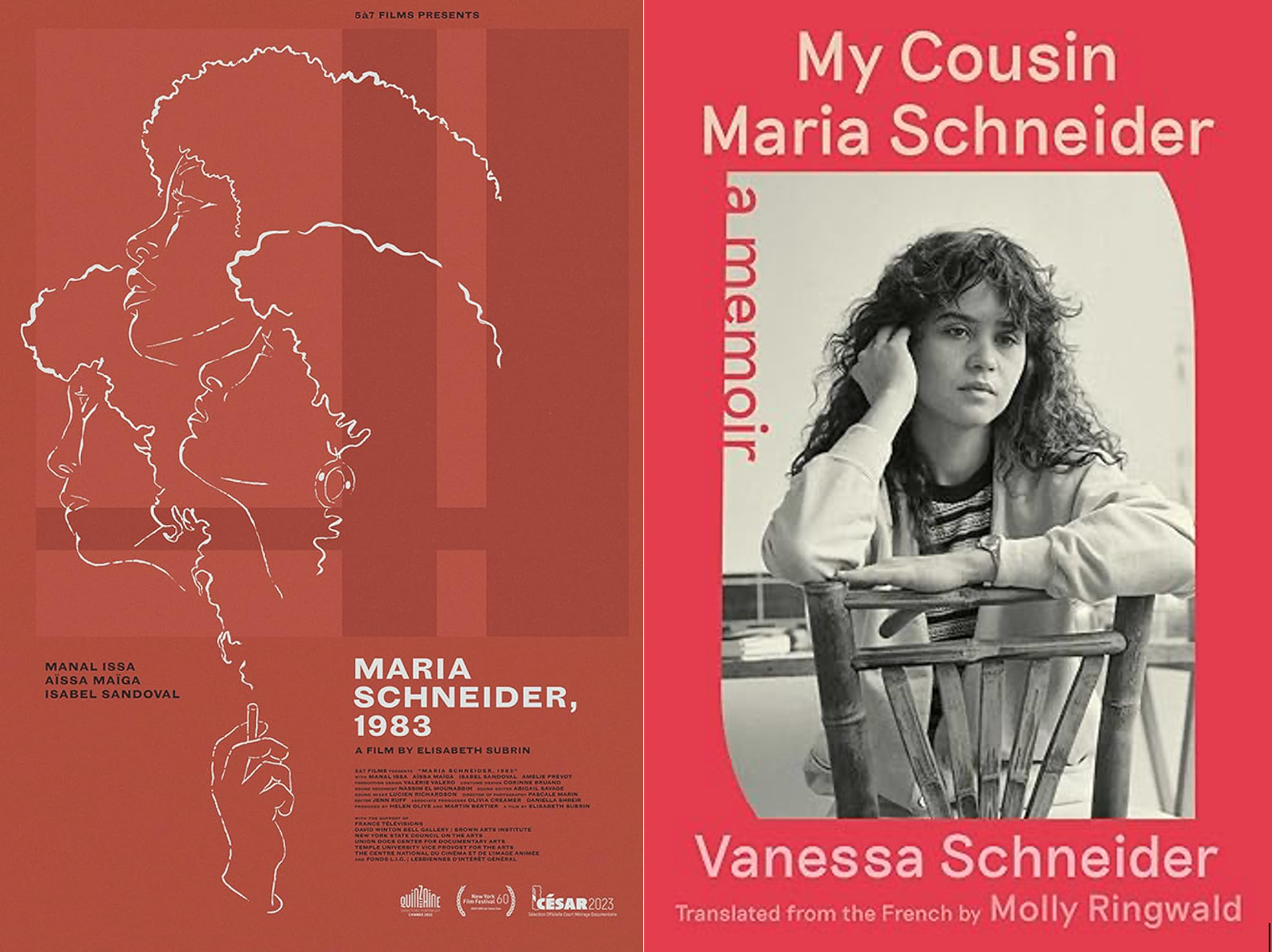

Hannah Bonner looks at Elisabeth Subrin’s documentary, “Maria Schneider, 1983,” alongside Vanessa Schneider’s memoir, “My Cousin Maria Schneider.”

By Hannah BonnerNovember 9, 2023

“I CAN’T RECOGNIZE YOU,” says the woman with the thick mane of hair, walking circles around the man. Her curls frame her face like a floral cartouche. Her eyes are dark, large, and hooded, betraying neither amusement nor concern. As she turns on her heel, the camera zooms in, framing her in a medium close-up. Her full lips part, poised for his answer. The mahogany wood in the background deepens the surrounding shadows of the Gaudí building they walk through, and the iron grate’s decorative molding echoes the woman’s signature leonine hair.

To describe an actress’s physicality in detail is always a fraught enterprise. We risk rendering the woman as an object of desire, rather than a living, breathing subject. Actress Maria Schneider is no stranger to such objectification. In the aforementioned scene from Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger (1975), she is the 23-year-old ingénue, credited only as “The Girl.”

This film, however, remained one of the actress’s personal favorites, as we know from a 1983 Cinéma cinémas talk-show interview Schneider did on a talk show run by film critic Michel Boujut and the director Claude Ventura. It is this interview that director Elisabeth Subrin thrice recreates in her short documentary Maria Schneider, 1983, which premiered at Cannes last year. Twenty-five minutes long, Subrin’s short film is deceptively simple: three actresses perform Schneider’s interview, one after the other, dressed in similar dark blazers and white crisp blouses with silver hoop earrings.

“The task of the translator,” Walter Benjamin writes, “consists in finding that intended effect upon the language into which he is translating which produces in it the echo of the original.” What is a description of an actress, or of acting itself, if not the translation of a face? Of dialogue and words? And what is acting if not the translation of real feeling into something manufactured and legible as performance? Manal Issa, Aïssa Maïga and Isabel Sandoval each play Schneider and, in doing so, remanufacture Schneider’s original interview in addition to editorializing based on their own unique views, thus imbuing their performances with real feeling, not just recitation. The screenplay both transcribes the original recording and allows for variations depending on the actress’s own identity and background. Issa is a Lebanese French actress in her thirties, Maïga is a Senegal-born French actress in her late forties, and Sandoval is a trans Filipina actress in her early forties.

The content of their dialogue in Maria Schneider, 1983 is, by and large, the same. Each iteration of Schneider’s interview begins with the line “Because actresses aren’t taken seriously.” But Issa credits such dismissal to an industry run largely by men; Maïga clarifies that these are white men who make casting decisions based on gender and race; Sandoval explains her own positioning as a trans actress, stating, “I refuse a lot [of roles] because I think there are few worthy women roles, few trans roles that I read that I want to do because we always make a woman exist in relation to a man.”

The actresses do not just speak as Schneider, but also for themselves. With each subsequent repetition, the performative documentary becomes as much about translating and embodying the ethos of Schneider on-screen as it is about these women vocalizing their own embodied experiences as actresses in a patriarchal and white supremacist industry.

In 1997, Subrin executed a similar cinematic translation in her film Shulie, a shot-for-shot remake of a 1960s documentary about feminist writer and activist Shulamith Firestone. The desire to not just reenact history but also overlay it in the present moment is an impulse that Shulie and Maria Schneider, 1983 share. The effect resurrects these women in the present moment while allowing the similarities of their material existences to speak to feminism’s ongoing struggle, in which bodily autonomy is not a given right and male predation still persists.

In Maria Schneider, 1983, Subrin films each performance in medium shots and close-ups, allowing the focus to remain on the actresses’ faces. Off-screen diegetic noise of a café peppers their dialogue: the clink of china, cutlery, and indecipherable chatter. At the end of Sandoval’s performance, the off-screen interviewer asks, “Did you feel uncomfortable on set during the shoot?” Sandoval’s gaze is imperceptible, and she remains silent as the camera pans away from her to sound recordists, the lighting equipment, the receding silhouette of either Issa or Maïga walking off set. One may initially mistake the interviewer’s question as pertaining to the film we have just watched, but, in fact, the original conversation ended on a tense discussion of Last Tango in Paris (1972) and Schneider’s physical and psychic violation on Bernardo Bertolucci’s set. Maria Schneider, 1983 is thus also a film about Schneider’s performance in Last Tango in Paris, the film that catapulted her to stardom when she was only 19 years old, starring opposite Marlon Brando, 29 years her senior.

The aftermath of this stardom, and its devastating consequences for Maria Schneider, is also the focus of Vanessa Schneider’s memoir My Cousin Maria Schneider, which was translated into English by actress Molly Ringwald and released by Scribner earlier this year. Schneider writes, “Your mother had to sign a waiver so you could accept the role.” Maria was still very much a child when Bertolucci and Brando conspired to simulate sodomy against her character on-screen. The scene is not in the script, and Schneider was not warned beforehand.

Vanessa Schneider continues:

It doesn’t matter that the sodomy was simulated—it makes you feel dirty and violated. You don’t understand that you could’ve prevented this scene from appearing in the film since it wasn’t in the script that you had agreed to. You could’ve called a lawyer, filed suit against the producers, and made Bertolucci cut it, but you’re young, alone, and poorly counseled. You know nothing yet about the rules and regulations of the film world. The perfect victim.

In Subrin’s film, the interviewer asks each version of Maria Schneider if this portrait can be accompanied by a scene from Last Tango in Paris. Each actress says no, begging for a clip from The Passenger, from anything else instead. Maria is marked by her role in Last Tango in Paris, forever associated with the violence and brutality of Bertolucci, who tells her on set, according to Vanessa Schneider, “You’re nothing. I discovered you. Go fuck yourself.” These moments seem to confirm Sandoval’s complaint that a woman must “always […] exist in relation to a man.”

Yet, Subrin displays rare generosity toward Maria by allowing her, and her alone, to speak. There are no men in Subrin’s film. There is no one questioning Schneider’s responses or refuting her claims. As Subrin’s credits roll, we hear Maria Schneider as The Girl from The Passenger saying, “Well, I’m in Barcelona. I’m talking to someone who might be someone else.” While Jack Nicholson’s character is the one to whom this dialogue is directed, we do not hear his reply. Subrin reworks both Schneider’s interview and Antonioni’s fictional diegesis so that Schneider can exist in relation to no one but herself—as well as the lineage of actresses who have followed in her wake.

After a lifetime of working in an industry run by men, the Maria Schneiders of Subrin’s film are working with a woman director, and the film’s associate producer, Daniella Shreir, is the founder and co-editor of Another Gaze, a feminist film journal dedicated to “women and queers as filmmakers, protagonists and spectators.” In terms of production, there is a marked difference in politics and parity from the historical context of the original interview and the present day.

If “[a] real translation is transparent,” as Benjamin would have it, it still “does not cover the original, does not block its light, but allows the pure language, as though reinforced by its own medium, to shine upon the original all the more fully.” Like concentric circles, Issa, Maïga, and Sandoval overlap one another, while sharing Maria Schneider as their center. The result is a documentary that goes beyond mere portraiture. Schneider is the speaking subject, but the gradations of interpretation of her interview offer a more holistic commentary on the Hollywood industry as a whole. The apparatus of this industry preys upon the young, the weak, the marginalized, and the disenfranchised, as Schneider’s story evinces, as so many other women’s stories do too. Schneider’s light is neither blocked nor distorted in Subrin’s deeply humanizing film: we are made keenly aware of her absence.

Vanessa Schneider also formally chooses to reevoke Maria’s absence through the use of the second person you. She writes as if speaking to her cousin, but her cousin cannot reply. “You felt our family’s history was personal,” Schneider writes. “You’d probably hate that I am writing about it again.” Such an admission raises the question of why Vanessa Schneider feels compelled to write the biography of Maria’s life, details of which include her heroin addiction, her mother’s cruelty, and the media’s recurring objectification of her, including the French newspaper Libération, whose obituary of Maria Schneider accompanies a photograph of her topless from Tango. Such an accrual of sordid details can feel at times like trawling through the most traumatic touchstones of Schneider’s life.

To ignore these formative details would be disingenuous—and yet, the recurring acknowledgment that Maria would not approve of such a book makes one wonder how Vanessa Schneider’s writing differs from any of the others that labeled Maria a “Lolita” or “Provocative Bambi.” Schneider intimates that her cousin would not welcome any attention—supportive or salacious, the affront is still the same.

Vanessa Schneider is self-reflexive in the process of writing this story, as much a story of her own childhood and family as it is a biography of her cousin, but the question of intent recurs. “I often worry that you won’t approve of the story I’m telling, Maria,” Schneider confesses. “So, I erase what I just wrote, and then I write it again, because talking about you without talking about the drugs, your mother, your father, or Tango would mean giving up talking about you at all.” She chronicles in clear, plainspoken prose the attempts to write about a much-maligned woman whose public persona never encapsulated her full interiority.

“What else happened?” Schneider writes towards the end of her book. “Perhaps I need to accept that I will never truly know.” This admission, while true, does not ultimately address the question of consent, a concept Schneider simultaneously evokes and just as easily elides.

“Without fail the little coincidences of life drive me toward you,” Schneider reflects, wittingly laying bare a life that, by all accounts, did not want to be exhumed. What responsibility do we owe to the dead, those who can no longer speak for themselves? Subrin’s documentary suggests both taking them at their word and fostering a collective community of women, a sisterhood that Maria Schneider did not experience as an actress within the industry. Subrin’s and Vanessa Schneider’s works center on the effect Maria has had on them, as artists and as women. The difference is that Vanessa chooses not to let her cousin “tell [her] side of the story.” To acknowledge a wish is not the same as honoring it.

Writing 43 years after Benjamin’s seminal essay, Susan Sontag encourages fellow contemporary critics “to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.” Subrin’s film allows us to listen to, as Vanessa Schneider writes, “[t]his question of status, yours and that of all women, [that] bothers you.” In examining one woman’s life, we discover echoes of our own and thus return to our own embodied existence, to our own corporeal bodies existing in time and space, aware of the past while also moving through the present. Though both Schneider’s book and Subrin’s film consider Maria Schneider’s effect on women, in Subrin’s film, “women” is a plurality, as opposed to Vanessa Schneider’s singular “I” or “you.” Though I do not take umbrage with either approach to biography, interpretation, or translation, one must acknowledge how Maria Schneider recurrently shuns the spotlight in Vanessa’s text, but not in the Cinéma cinémas interview, or Subrin’s film.

In Maria Schneider, 1983, Maria is always already aware of the camera. In My Cousin Maria Schneider, she never consents to the recording.

¤

Hannah Bonner is currently a creative nonfiction MFA candidate at the University of Iowa.

LARB Contributor

Hannah Bonner’s essays and criticism have appeared, or are forthcoming, in Another Gaze, Bright Wall/Dark Room, Cleveland Review of Books, Literary Hub, The Rumpus, The Sewanee Review, and Senses of Cinema. She is a 2023–24 NBCC Emerging Critics Fellow and a graduate of the creative nonfiction MFA program at the University of Iowa, where she also earned an MA in film studies. Her first poetry collection, Another Woman, is forthcoming from EastOver Press.

LARB Staff Recommendations

What the Center Holds: On Carl Elsaesser’s “Home When You Return”

Hannah Bonner considers the smudge in Carl Elsaesser’s 2021 film “Home When You Return.”

Cinema in a Little Mirror: The Hays Code and Cultural Dysphoria

Katharine Coldiron looks at the cultural dysphoria caused by the Hays Code in US cinema.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!