Cinema in a Little Mirror: The Hays Code and Cultural Dysphoria

Katharine Coldiron looks at the cultural dysphoria caused by the Hays Code in US cinema.

By Katharine ColdironMay 3, 2023

PRE-CODE FILMS are hard to watch, and not just because they’re often hard to find. The movies made just prior to the

1934

implementation of the Hays Code—a set of strict censorship rules enforced against Hollywood films from the mid-1930s to the late 1960s—inhabited a unique period characterized by the shift toward sound film that began in 1927. Cinema was in a state of transition during those seven years: moguls consolidated power, standby genres lost popularity, and others popped up anew. Those years saw a near-total changeover in the names and faces most beloved by audiences. And the grammar of cinema shifted too.

The transition to sound remade the art form in more ways than the obvious one. Editors and directors needed to learn whole new styles of timing and rhythm once the movies learned to speak. Hence, early sound pictures, which overlap to a large degree with pre-Code films, often feel awkward to modern audiences. The scenes or shots go on too long. The actors appear to monologize loudly to themselves rather than talking to each other. Fade-outs happen before the joke is complete.

Despite these challenges, pre-Code movies often prove revelatory to audiences that bear with them. The people in these films have the same problems we do, nearly a century later: mixed emotions around family bonds, lovers who want too much or too little, jobs that ask more of us than we want to give. These characters struggle with money, make mistakes and muddle through them, and cope with competing life priorities. The Hays Code—although this was not its stated purpose—flattened out these vibrancies and transformed realistic human characters into paper dolls that pushed plots around the studio backlot like uneaten vegetables on a dinner plate.

This may sound like exaggeration. But because the Code was so grounded in moralism, rather than realism, it discouraged ambiguity of all kinds. Families were usually loving and whole, rather than disappointing or healthier after splitting up. People presented in a positive light, particularly women, rarely had vices or lost their tempers. If a protagonist made mistakes, he earned punishment, not a lesson. The colors of real life cannot be developed on film stock imbued with such black-and-white morals.

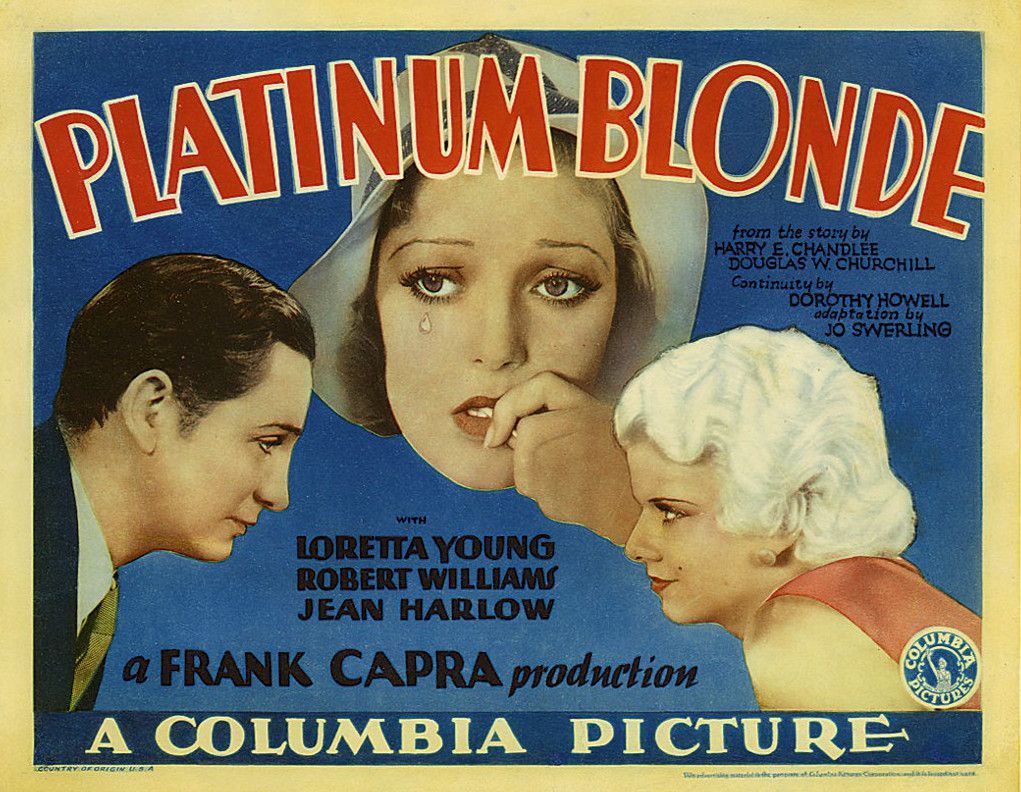

Compare two films about people who marry in haste: Platinum Blonde (1931), an early Frank Capra picture with Jean Harlow, Robert Williams, and Loretta Young; and Suspicion (1941), an Alfred Hitchcock film with Joan Fontaine and Cary Grant. In both films, the protagonist marries someone irresistible without realizing their essential incompatibility as a partner. Blonde is a lighter film, a frothy newspaper comedy, while Suspicion is a suspense drama adapted from an even darker novel. Each protagonist makes a different choice about their bad marriage; one reflects reality, the other a moralistic fantasy.

In Platinum Blonde, a newspaperman, Stew (Williams), marries socialite Anne (Harlow) after they fall terribly in love. Hijinks ensue as Anne tries to convince Stew to loaf respectably rather than working, and Stew tries to convince Anne that he’s happy without sock garters. Meanwhile, a good-hearted female journalist, Gallagher (Young), waits unrequited for the marriage to founder. The plot is secondary to the chemistry, the snappy lines, and the cast. Harlow was about to peak in fame, and Williams, who died unexpectedly just days after the film premiered, could have been the great everyman comedian of the 1930s.

At the end of the film, Stew realizes he made a mistake in marrying Anne and decides to divorce her. Anne is not a bad woman, and the marriage isn’t abusive, adulterous, or otherwise intolerable. The pair are simply wrong for each other. They eloped due to passion, with no regard for suitability. It’s a starter marriage. Today this is a reasonable idea, even a common one, and seeing it play out in approximately the same way in 1931 as it would in 2023 forms a remarkable bridge across time.

But between the mid-1930s and the late 1960s, the board of Hollywood film censors found divorce unseemly. The Code specified that “the sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld.” In most Code-era movies, divorce was a last resort, only to occur when one spouse was decidedly bad. Divorce almost couldn’t be imagined between two people who were good, but who were bad for each other. (There are exceptions—lots of movies slipped under the limbo stick of the Hays Code—but space prevents discussing them all.) Even if the two people were very, very bad for each other, the Code insisted that they ought to try and make it work.

Thus, Suspicion. In it, a rich, sheltered young woman named Lina (Fontaine) and a flashy social climber, Johnnie (Grant) marry as recklessly as Stew and Anne do. The roles are somewhat gender-swapped; both the socialite Lina and the reporter Stew have caught a rare, beautiful animal and somehow convinced it to stay on a leash. Both playboy Johnnie in Suspicion and high-class Anne in Blonde try to fold their new spouses into an extravagant lifestyle. However, in both films, the woman is the one with the money.

After the honeymoon, Lina discovers that Johnnie is a jobless gambler and something of a con man. He’s been living way beyond his means, and he intended to mooch off Lina’s family after their marriage. Johnnie’s lies escalate until Lina suspects him of murdering an acquaintance, and eventually of trying to murder her as well.

After she discovers a particularly atrocious lie, Lina packs a suitcase and writes a letter to Johnnie, intending to leave him. But she changes her mind, unpacks, and tears the letter up. The movie presents this decision as the result of Lina being too in love with Johnnie not to try and make the marriage work.

In the final minutes of the film, Lina discovers that she was wrong: Johnnie meant only to kill himself. He repents, she takes him back, and they return home together. Hitchcock himself complained about this ending in later years, and with good reason, as it’s rushed and unconvincing.

In the book, Johnnie is guilty of the acquaintance’s murder, as well as unchecked adultery and thievery. The final pages indicate that he does indeed poison his wife. The film rewrites Johnnie’s villainous nature into mere irresponsibility, and simultaneously discredits Lina’s judgment and rationality. That is, the film implies that Lina jumps to ridiculous conclusions in believing him capable of murder and trying to leave him. Yet, if she’s right, and not crazy, isn’t she a fool to stay? Either choice is the wrong one.

These are the kinds of knots into which the Hays Code forced films to tie themselves. Ultimately, Suspicion wants the audience to believe that, especially for a woman, being wed to a charming murderer is better than the shame of divorcing him. Divorce was portrayed as so unthinkable that people in extremis, like Lina, could not in good conscience pursue it, much less people in ordinary, incompatible marriages.

Which is why pre-Code films appear liberal and relatable by comparison. When Stew finally realizes that his marriage to Anne is not going to work, it’s a familiar kind of indignation he expresses. Anyone who has hit a breaking point in a serious relationship understands it. Even accounting for the extreme stakes in Suspicion, it’s much harder to relate to Lina’s desperation to keep her marriage afloat.

The later film is far more sterile than the pre-Code one. It is not hard to imagine being wildly attracted to Cary Grant, but that is fortunate casting, not good filmmaking. Platinum Blonde, meanwhile, includes a passionate scene between Stew and Anne beside a glass fountain streaming with water, one that makes it plain why they’d marry without thinking it through.

The Hays Code, and its enforcement, easily explains the differences in these films, but it elucidates a lot more about the shape of the 20th century besides. Deliberately, with racism and sexism aforethought, the Hays Code reflected an exceptionally narrow band of human experience. It was composed and enforced by men who had a specific idea of what movie audiences should be exposed to, and that meant the mirror of cinema shrank unacceptably to the point where only cisgender, white, straight, Christian people could see themselves in it. Since everyone else was excluded—despite pre-Code movies showing clearly that they existed long before the 1970s—their lives and realities were suppressed or ignored. At a time when cinema was a far more homogeneous national media experience than it is now, the movies didn’t frequently show happy divorced women, or professional Black men, or queer people with regular lives. If moviegoers who could see themselves in the little mirror never encountered any other kinds of people in real life, for whatever reason, they might well have believed that such people did not exist.

For 30 years, this cultural dysphoria was the norm.

The Code did not fall like the Berlin Wall, on one fateful day; it disintegrated over a period of years. The reasons for its decline are thoroughly covered elsewhere—Thomas Doherty’s Hollywood’s Censor: Joseph I. Breen & the Production Code Administration (2007) and Mick LaSalle’s Complicated Women: Sex and Power in Pre-Code Hollywood (2000) are two definitive books on the Code, although there are many others—but it became quite toothless by the end of the 1960s. During that decade, an influx of European films demonstrated how distorted the mirror really was, and they gave audiences a taste of real, regular life, in all its complexity and pain and joy. Nothing like that had been on screens in the United States since Gold Diggers of 1933 (released the same year) or I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932).

Mark Harris’s wonderful book about 1967’s Best Picture nominees, Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood (2009), explains that Hollywood in that year was poised on the brink of reinvention. The studio system was a shadow of its former self. Stars had stopped signing their lives away, and audiences were no longer impressed by the heavy glitz of classical filmmaking.

The latter half of the 1960s was a watershed period in American cultural life as well. The Civil Rights, Women’s Liberation, and Gay Liberation movements all maintained unprecedented momentum in those years. Is it a coincidence that once the shackles of the Hays Code began to fall—once the mirror widened out, and people of all kinds began to see themselves in the movies—society as a whole began to open its mind too?

It is impossible to know if the Code years actually delayed any of these social movements, or if they required other cultural factors to bloom when they did. But it feels to this critic as if all the liveliness and realism of pre-Code films froze in place during the decades that followed, and the subsequent chill blew into every theater in the United States.

In the universe within Code movies, it seems as if people lived happily, sexlessly, without queerness or disability or mental illness or any other inconformity. If dissatisfaction cropped up, it was easily resolved by digging in to traditional values. This is not a true representation of life. Life has always been chaotic and gorgeous and difficult, and pre-Code movies mirror more of that beautiful chaos. People in pre-Code movies lose their tempers, marry the wrong person, let ambition get the best of them. The mistakes they make are not held out as the wages of sin; they’re just mistakes, and characters either figure out how to fix them or don’t. And life goes on.

It’s often messy, but that’s life: messy, challenging, unboxed. Pre-Code movies can be described with these three adjectives too. Suspicion cannot. But Platinum Blonde can.

¤

As a kind of epilogue: I hope this essay causes you to seek out Platinum Blonde, but be advised that it exhibits some racist tropes, including the phrase “white, male, and over 21” (a reference to a common idiom then) and a short but atrocious faux–Native American sketch. And if I were to recommend one pre-Code film that could truly astonish contemporary audiences over how libertine life was at the time, it would be Female (1933). Ruth Chatterton portrays the head of a car company who shops her factory floor for bedfellows.

¤

LARB Contributor

Katharine Coldiron is the author of Ceremonials (2020), a novella inspired by Florence + the Machine, and Junk Film: Why Bad Movies Matter (2023), a collection of essays about bad movies. Her essays and criticism have appeared in Ms., Conjunctions, The Washington Post, The Guardian, Los Angeles Review of Books, The Rumpus, and many other places. Find her at kcoldiron.com or on Twitter @ferrifrigida.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Out of Necessity: On Christine Hume’s “Everything I Never Wanted to Know”

Juliana Spahr reviews Christine Hume’s “Everything I Never Wanted to Know.”

Who Owns Dungeons & Dragons?

Emily Friedman writes about intellectual property and Dungeons and Dragons.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!