Look Again! A Conversation with Irish Artist-Novelist Sara Baume

Amy E. Elkins talks with artist-novelist Sara Baume about cross-media inspiration, scratch-made art, and miniaturization on the page.

By Amy E. ElkinsOctober 12, 2018

I’M SETTLED INTO the passenger seat of Sara Baume’s red truck as she deftly maneuvers down dirt roads dotted with farms and abandoned famine-era cottages. We reach a 1920s farmhouse, her home and studio, and I’m greeted by a ferocious terrier, a benevolent greyhound, and a field of lowing cows who look up curiously from their meal of dry grass.

Drought and heat waves have besieged Ireland this summer, but the creative energy flooding Baume’s corner of the world is palpable. Author of the novels Spill Simmer Falter Wither and A Line Made by Walking, Baume is a trained sculptor and practicing artist who engages the visual arts with striking originality in her literary work. Over lunch in her sea-facing garden, we discussed the fertile cross-media relationship between her artistic practice and her writing.

¤

AMY ELKINS: Frankie, the protagonist of A Line Made by Walking, trades art school for the solitude of her late grandmother’s abandoned home in rural Ireland. She begins a meaningful, meandering art project that comprises a photographic series of dead animals. I later learned that the Irish and UK editions of the book include photographs of the animals — taken by you — but the US edition omits them (though the galley proof includes boxes where photos would go). Fill the gaps for us. What was the process of taking the photographs like? How did you envision them fitting into the novel?

SARA BAUME: The photos as a collection actually existed several years before the novel was written. Initially, I wasn’t taking them for any particular reason, just out of curiosity. If I came across a dead creature and my camera was reasonably handy, I’d photograph it. After a couple years, I realized I’d built quite the collection. I had a vague sense I might use them in a project someday, and then in 2009 I incorporated them into an installation for a group exhibition in Gorzów, Poland. The installation also included little animal effigies carved from balsa wood — one to match each photo.

I didn’t start the novel in a focused way until 2015. At that stage my first novel had done quite well, and I felt that gave me the green light to try something a bit more experimental. I’d always been interested in fiction that makes space for pictures whilst maintaining a certain seriousness. W. G. Sebald is a big influence, and because of him I wanted the animal photographs to appear embedded in the text: where the narrator finds the dead creature, the reader finds a photograph. I asked for this in publication but was never forceful about it — each editor had the final call.

I see — the reader participates in the discovery, too! The Irish edition, published by Tramp Press in a beautiful limited run of 200 signed copies, presents the photos in another way: they are cropped square and placed ahead of chapters rather than embedded in the text. Does the cropped layout change how readers understand Frankie’s practice as a photographer?

To begin, maybe it’s important to clarify that Frankie doesn’t think of herself as a photographer; she just uses photography as a tool of her art practice. Which is just the same as me. I’d never claim to be a photographer, but in almost every case a project will begin with a photograph or series of photographs. They are source material and later, usually, discarded. With my current souvenir-plates project, for example, each one started with a blurry snap on my smartphone of a banal pattern I encountered while traveling overseas. Later, I copied the patterns into a notebook and, finally, painted them onto acrylic-primed china plates.

But back to the question! Yes, certainly the animal pictures become something different once cropped and positioned as title pages. I would imagine that it makes it more difficult for the reader, even just on a subconscious level, to relate them to Frankie’s experiences. As for the cropping, I guess that enforces the design aesthetic by making them seem less like real photographs, less like artifacts from the world, and more like embellishment.

In one of our earlier conversations, you mentioned the term “scratch-made.” Could you expand on that a bit? How does this idea of DIY or the scratch-made art object contribute to the subversive function of your work?

I think it was in reference to amateur railway modelers that I first came across this term. It was describing something like a model signal tower for which every part has been composed from scratch as opposed to bought ready-made in a box, as part of a kit or whatever. In my artwork, I tend to employ the materials of amateur craft — modeling clay, balsa wood, dowels, varnish — but I never follow the given rules of amateur craft, or any specific craft. I instead try to build objects as much as possible from scratch.

Just recently, I realized I approach writing by the same means, or apply the same strategies to both practices: initially harvest fragments from my surroundings, habitually embellish or obscure from reality, ultimately piece everything into a form of narrative … or a narrative-made form?!

In Spill Simmer Falter Wither, the protagonist chooses his dog at the pound by pointing to a “miniature photograph” of the dog’s “miniaturized nose.” This is something you later explored in a sculpture project of miniature clay dog figurines. Editions of A Line Made by Walking that include photographs turn those animals into miniatures, too. Scale clearly interests you, and you’re able to transport the idea of the miniature across media. How did you develop this interest, and does this practice influence how you write or think about imagery on the page?

You know, I’ve been exploring this in my work; only just recently have I started to embrace it. In art school, whatever I made, the tutors would always say, Make it bigger bigger bigger! So for years, smallness was, in my mind, synonymous with a kind of failure. It’s only now I’m old enough to feel I can indulge that impulse, so long as I also stop and examine it somehow. I’m a fan of Susan Stewart on the subject:

The miniature linked to nostalgic versions of childhood and history, presents a diminutive, and thereby manipulatable, version of experience, a version which is domesticated and protected from contamination.

She writes wonderfully on dollhouses as well, how making things small, compartmentalizing them in a certain way, is a means of exerting control over an essentially uncontrollable universe. And the souvenir is, according to Stewart, “the preservation of an instant in time through a reduction of physical dimensions and a corresponding increase in significance supplied by means of narrative.”

I like your suggestion of transporting the idea across media. Immediately, I was going to try to think of examples in my writing and instead I thought, Isn’t all of writing a way of miniaturizing and containing experience, really?

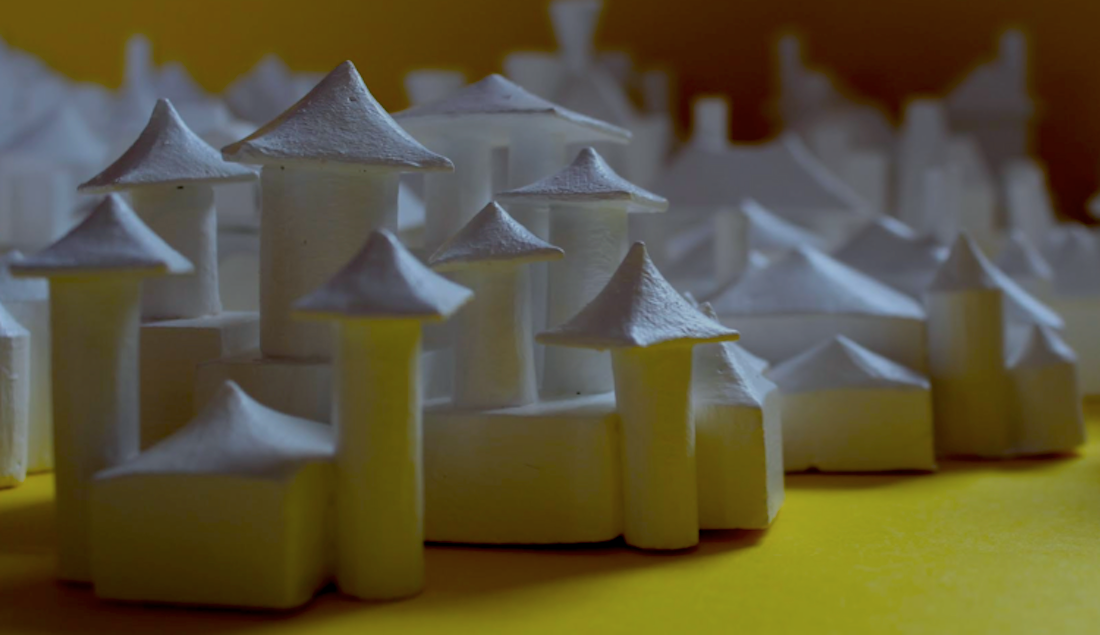

Absolutely! Also, having seen the cottages for your upcoming installation, I’m struck with how you combine Stewart’s conception of the miniature as nostalgic medium with the destabilizing potential of scale and multiplicity. How do those coalesce in the cottage project?

The “official” title of the project is Talismans. All going to plan, once installed it will be a 40-foot skyline of miniature houses carved to the scale of traditional Irish-cottage souvenirs but in the style of contemporary rural dwellings, specifically the hideous “monster mansions” — large, asymmetrical, endowed with an abundance of skylights, dormer windows, turrets, and conservatories — that popped up all over the countryside in the years of the Celtic Tiger. The style sort of degenerates as the skyline goes on: the “cottages” become almost entirely abstract, more like little stacks of toy blocks than anything resembling a house. In a blurb for the project, I wrote, “Rural Ireland and its transfiguration is a subject which haunts my fiction; these talismans were made as a means of construing my anxieties around ideas and issues of landscape and of home.”

To be completely honest, I think I make small objects only ever in multiple as a means of compensating for their smallness. They are monumental in my imagination, and in the effort and hours that go into each, and in the affection I have for them, so making many is a way of saying without saying, Look again! Look again! Look again!

Is writing a novel more like taking a photograph or making a sculpture?

Writing a novel is, for me, an almost identical process to making a sculpture, or, perhaps more accurately, making an installation. We talked about multiples above, so I guess if each sentence is a single object, then the novel is the whole installation.

¤

LARB Contributor

Amy E. Elkins is a writer, scholar, and multimedia artist. She is an associate professor of English at Macalester College and the author of Crafting Feminism from Literary Modernism to the Multimedia Present (Oxford University Press, 2022). Her scholarship and art appear in such places as Modernism/modernity Print Plus, PMLA, Contemporary Literature, Inscription, and Post45 Contemporaries. In addition to interdisciplinary collaboration and leading community arts events, she lectures on experimental and feminist approaches to pedagogy and archives. Her research on late 19th-century to contemporary literature focuses on visual culture, queer theory, and everyday practices of well-being, community, and cross-cultural activism. You can find her at amyelkins.net.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Second Acts: A Second Look at Second Books of Poetry: Susan Stewart and Jennifer Chang

Lisa Russ Spaar appreciates the lyric intelligence of Susan Stewart’s and Jennifer Chang’s second collections.

The Strange, Irreverent Worlds of “Down Below” and “The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington”

Emily Wells looks at two new rereleases from Leonora Carrington.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!