“For 25 Years I’ve Kept Something from You”: “Twin Peaks” in Print

A survey of books on, in, and about “Twin Peaks.”

By Andrew HagemanJanuary 16, 2018

“FOR 25 YEARS I’ve kept something from you” is a line of dialogue spoken by FBI Deputy Director Gordon Cole (played in wonderful deadpan style by David Lynch) in the penultimate episode of the 2017 television series Twin Peaks: The Return. True to form, the line conjures up the promise of a deep revelation, only to be followed by information that, due to its seeming simplicity, is so opaque it only reinforces the mysteries at the heart of the program. While the prospect of another season is unlikely despite the show’s critical success, fans of the series can revel in an extended Twin Peaks universe of merchandise, academic and popular criticism, and print fiction. This final category includes series co-creator Mark Frost’s two recent novels, The Secret History of Twin Peaks (2016) and Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier (2017), as well as a wealth of previous titles.

Both of Frost’s books are presented as documentary archives, replete with newspaper clippings, top-secret memos, transcripts of interviews, and other materials. The Secret History of Twin Peaks provides an overview of the Twin Peaks area, from its indigenous history, to its founding in the late 19th century, to its 20th-century encounters with various paranormal phenomena, while The Final Dossier explores the temporal gap between the cancellation of the original series in 1991 and the debut of The Return in 2017. Though the books do not provide closure on some of the show’s core enigmas, they do offer sustained encounters with its history, characters, and environment, in the process demonstrating how crucial Frost’s role has been in shaping this wonderful and strange American place.

The heart of The Secret History is its distinction between mysteries and secrets. In an early passage, the “Archivist” who compiled this documentary history comments:

Mysteries precede humankind, envelop us and draw us forward into exploration and wonder. Secrets are the work of humankind, a covert and often insidious way to gather, withhold or impose power. Do not confuse the pursuit of one with the manipulation of the other.

Given how centrally these two entangled concepts feature in the series, this passage — and others like it threaded throughout the book — offers insight into their relationship to natural wonder on the one hand and manmade structures of power and exploitation on the other. It’s particularly suggestive that the above passage occurs when the Archivist is relating the early history of indigenous inhabitants and their encounter with — and displacement by — European explorers in the region.

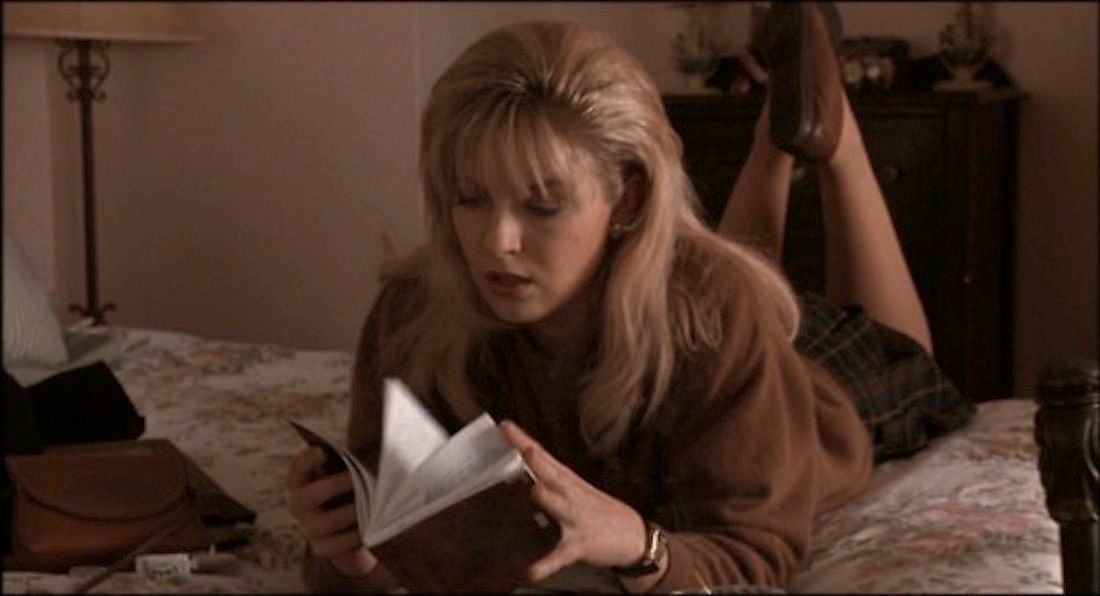

The Archivist’s volume was discovered by investigators at a crime scene (later specified in The Final Dossier), and Deputy Director Cole has tasked Agent Tamara Preston with performing a comprehensive analysis of it. Tammy Preston plays a key role in The Return, and this book is our introduction to her. The Secret History conveys her character subtly and indirectly — we do not even know her full identity (including her gender) until the final page. By contrast with quirky Special Agent Dale Cooper, Preston is more circumspect, as when she analyzes a front-page story in the Twin Peaks Post about the bank explosion that ended Season Two:

Kind of quaint, isn’t it, how news was still being disseminated in print during these last days before the Internet. If it weren’t for all the murders and explosions and dizzying double-crosses, I’d be tempted to say it seemed like a more innocent time.

Frost thus takes readers back to the series’s bizarre twists and turns through an outsider’s perspective — a format designed perhaps to draw a new generation of fans into the Twin Peaks universe.

Highlights of The Secret History include its extended engagement with the careers of Douglas Milford, brother of the town’s mayor, and Major Garland Briggs, both of whom take on roles more central than the original series suggested, especially the former. In treating these two characters, Frost dives deep into the supernatural, extraterrestrial, and conspiracy-theory aspects of the show in a way that is no less bonkers than Season Two while also being cohesive, compelling, and, most of all, fun. For those who prefer the more folksy aspects of the series, Frost explores the backstory of the Double R Diner and its damn fine coffee and pie.

Frost’s two novels are not the first Twin Peaks tie-ins. During the first season’s run in 1990, Jennifer Lynch (David’s daughter) published The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer, which — like the prequel film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992) — provides harrowing access to Laura’s very dark secrets. It’s a devastating self-portrait that retroactively acquires new import in light of The Return. For example, the November 10, 1985, entry in the diary reads:

I kept seeing this address in my head, each time I finished a thought, no matter what it was, and finally I found myself in front of this very old, abandoned gas station. […] When I walked around Troy [a pony that Ben Horne clandestinely gave her as a birthday present], so that I was completely facing the station, I saw the Log Lady standing very quiet with her log.

This encounter, sparked by a daydream vision, made a deep impression on Laura, and readers who have witnessed the weird power of abandoned gas stations and of the Log Lady’s prescience in The Return cannot help but think of the fractured timeline of Laura’s story that unfolds in its last two episodes.

Another book published at the time of the original series, The Autobiography of F.B.I. Special Agent Dale Cooper: My Life, My Tapes (1991), written by Scott Frost (Mark’s brother), takes on new meaning in the wake of The Return. For example, consider the sequence of short entries about a family trip to Mount Rushmore in July 1973, where Cooper’s father wages a one-man protest outside the information booth by brandishing a sign reading: “GIVE IT BACK TO THE SIOUX!” Cooper’s account of this trip anticipates the engagement with indigenous peoples in Frost’s Secret History, and it echoes a scene in “Part 4” of The Return where Gordon Cole, surprised while driving through South Dakota that he is nowhere near Mount Rushmore, responds in his typical deadpan style to a photo of the site: “There they are … faces of stone.” Another passage in the autobiography records Cooper’s experience of being banned from a Las Vegas casino for consistently winning, a prefiguration of his doppelgänger Dougie’s hilarious jackpot streak in The Return. While The Autobiography appears to be a collection of idea seeds that came to fruition in the show’s recent season, it can also be read as an indication that Cooper is bound to multiple timelines of repetition and difference, a possibility raised in The Return’s delirious finale.

The final book published during the original series’s run was Welcome to Twin Peaks: Access Guide to the Town (1991), written by David Lynch, Mark Frost, and Richard Saul Wurman. This tour book provides intriguing glimpses of character backstories alongside eccentric trivia such as charts displaying the range of wood profiles sawed at the Packard Mill and various specialty tools used in the early days of logging. Foreshadowing Frost’s recent novels are passages unveiling the geographic and cultural history of the Twin Peaks area. The Access Guide, however, privileges the accounts of the town’s first families, such as the Packards and the Hornes, while Frost’s Secret History focuses on the role and contributions of indigenous peoples.

An arcane print inspiration for the esoteric mythos of Twin Peaks is the 1926 novel The Devil’s Guard, by Talbot Mundy. The narrative follows the intrepid Jimgrim and his band of adventurers as they search Tibet for the fabled Shambhala. Although plagued by an insipid protagonist, ill-paced plotting, and a reprehensible Orientalism, the novel warrants reading by devoted Twin Peaks fans for its detailed engagement with the concept of dueling Black and White Lodges and the dugpas, or black magicians, who inhabit the former. In light of the magical centrality of electricity in The Return, passages such as this are particularly provocative:

Neither does the White Lodge make distinctions. It is secret, just as electricity was secret before Thales, Gilbert, Faraday, and all the others following them, discovered something about it. Electricity was there, always, but they had to find it; and having found it they could give it to the world, to use or misuse. Was electricity confined to one place? No. Neither is the White Lodge confined to any one place. But some places are more suitable than others, just as there are certain places where it is more practical to establish electric plants. Climate has a lot to do with thinking.

A more direct tie-in was the trove of Twin Peaks fan fiction produced for the Yahoo Group “The Bookhouse Boys” from 1999 to 2005. (The archive went offline in 2013 but can be accessed via the Wayback Machine.) This compendium includes a piece of slash fiction, entitled “Beard Burn,” that builds upon the fraught relationship between Sheriff Harry S. Truman and Agent Albert Rosenfield in the original series.

Some recent critical work on Twin Peaks also merits attention. H. Perry Horton’s self-published Between Two Worlds: Perspectives on Twin Peaks (2016) brings a devotee’s meticulous focus to themes of water, love, food, genre, and loneliness in the original series. Horton also advances the arresting if controversial thesis that Lynch’s 2001 film Mulholland Drive is set in the same fictional universe as Twin Peaks. By contrast, Andreas Halskov’s more academic TV Peaks: Twin Peaks and Modern Television Drama (2015) provides a formidable analysis of the show’s central role in the contemporary TV landscape. Finally, the most recent contribution to Twin Peaks criticism is Blue Rose Magazine, whose four quarterly issues published in 2017 feature shrewd episode-by-episode analyses of The Return by John Thorne, co-founder of the long-running fanzine Wrapped in Plastic.

Frost’s capping contribution, Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier, released last Halloween, affords a wealth of surprises, elucidations, and ruminations regarding the series’s characters. At one point, the career of a minor figure intersects with a certain flamboyant, egotistical New York billionaire, while the psychedelic backstory of Dr. Jacoby reveals deep links with Jerry Garcia and his line of designer ties. There’s a stunning revelation that the young Sarah Palmer lived in New Mexico during the 1950s and was exposed to the unsettling radio broadcast in the “Gotta Light?” episode of The Return. The fate of Audrey Horne, so mysterious throughout the new season, eludes ultimate explanation, yet there are a couple of juicy details that Frost saved for this book. Along the way, Frost spices the dossier with self-deprecating jabs about storytelling decisions and elisions across the series.

Agent Preston, analyst of the archive volume in The Secret History, has graduated to authorship of The Final Dossier, and the self she reveals through her writing diverges further from the folksy and exuberant Dale Cooper. By contrast with Cooper’s fondness for paradox and dream logic, Preston approaches her casework with relentless objectivity and skepticism. Among her last remarks, Preston writes, “What if the truth lies just beyond the limits of our fear, and the only way to reach it is to never look away? What if that’s why we must keep going, why we can never quit trying to overcome it in every moment we’re alive?” The various books of Twin Peaks — those mentioned here as well as others — are invitations to keep going, to seek out mysteries and debunk secrets; they are invitations to love Twin Peaks far into the future, on a timeline that may never include another new episode.

¤

Special thanks to a damn fine research assistant, Jane Peña, for helping me with all things Twin Peaks.

¤

Andrew Hageman is associate professor of English at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa.

LARB Contributor

Andrew is assistant professor of English at Luther College in Decorah, Iowa, where he researches and teaches the intersections of ecology and techno-culture in literature, film, and the arts. He’s published articles on matters that range from David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive and Twin Peaks to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Paolo Bacigalupi’s fiction, and ecology and ideology in Althusser and Žižek. Most recently he co-edited a 2016 issue of Paradoxa on “Global Weirding.”

LARB Staff Recommendations

David Lynch’s Late Style

Jonathan Foltz on “Twin Peaks: The Return.”

Return of the Naïve Genius: “David Lynch: The Art Life” and “Twin Peaks: The Return”

Reading any interview with Lynch since the release of "Eraserhead" leaves open the question of whether the director performs his innocent remoteness.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!