David Lynch’s Late Style

Jonathan Foltz on “Twin Peaks: The Return.”

By Jonathan FoltzNovember 12, 2017

BEFORE THE MIND-BENDING abstractions and derelict poetry of its fabled eighth episode, before the long-anticipated awakening of Agent Cooper, and long before the horrific, shattering final scream that plunged us into new dimensions of uncertainty, Twin Peaks: The Return introduced us to an unassuming mechanic named Jack. Like many of the minor characters this season, you might not remember his name. His face is a different story.

We first meet him in the quiet corner of a diner booth, mindlessly tucking in to an abject plate of spaghetti, his third. “Jack, you barely touched your three dinners,” jokes Ray at his most insufferable. There is a great deal of important foreshadowing and exposition going on in this scene, hints about Ray and Daria’s betrayal, Mr. C’s hunt for coordinates, his impending re-entry into the Black Lodge, even his metaphysical status as a creature of pure drive and malevolent desire. (“If there’s one thing you should know about me, Ray,” Mr. C intones with hypnotic force, “it’s that I don’t need anything. I want.”) During this moody dramatic standoff, Jack never so much as looks up from his pasta. He never speaks. He’s a decorative piece of the scene’s symbolic furniture, a depressed image of a mechanic with a mechanical appetite, his stacked plates of spaghetti forming a miserable counterpoint to Mr. C’s demonic tough-guy posturing about need versus want. Why do we take more than we need? It is the sort of question that feels central to Twin Peaks and its glutton’s world of donuts and pie and metaphysical creamed corn: what happens to us, and to our souls, when we consume too much?

The next time we see Jack, he is standing outside a garage, locking up the Mercedes in which Mr. C made his haunting entrance into the series, and handing over the keys to a 2003 Lincoln Town Car (the same car, by the way, that the real Cooper, if it is the real Cooper, drives from Odessa to Twin Peaks in the last episode). On first viewing, it is unclear why Mr. C needs to change out his sleek Mercedes for the next segment of his evil deeds, just as it is unclear why Lynch even bothers to create a character whose sole narrative purpose seems to be to facilitate this one exchange. But before we have time to fully formulate these questions, Mr. C summons Jack to his side. Wordlessly, with an expression at once sinister and pitying, Mr. C reaches out with his hand to cup and hold Jack’s face, slowly manipulating the folds of his submissive skin as though he were a puppet forming a set of imaginary words.

Lynch holds on this scene for an uncomfortable amount of time, lavishing seven cuts and nearly a minute of footage on Mr. C’s tactile show of dominance, the effect of his gesture passing from intimidation to a strange kind of tenderness, registering the tragic feeling of the strong for the weak they nonetheless mean to exploit. We later find out that Jack gets murdered in this scene, but we never see the act take place. His death, we feel, is already written in the lines of this gruff but malleable face, the skin gone slack, vulnerable, now just an unresisting sculptural material for the dark forces that menace and shape it. In this gloriously inexpressive pause, Mr. C seems to be asking himself: what can this goony, docile face be made to sing?

In many ways, this long squeeze is perfectly representative of the oblique, beguiling aesthetic of the new Twin Peaks. It is not only that the pace is so exquisitely slow or that the scene’s narrative purpose is unclear. We are also left to wonder about the spotlight of lyrical dread lavished upon a character so soon to disappear from the story, just as we may be disarmed by the proliferation of arresting minor characters, stray images, and tangential action throughout the series.

Lynch has always had a way of elevating peripheral performances to derail our sense of narrative logic (think of the man in Wild at Heart who quacks like a duck, or the inexplicable presence of anthropomorphic rabbits in Inland Empire). But no work of Lynch’s has been so gloriously digressive as Twin Peaks: The Return, nor has any work of his been so elliptical or so unforgivingly distracted by the characters, images, and scenes that seem to exist to the side of its story line. In this, the series embraces a narrative style that is arguably even more inventive and jarring than the narrative itself, with its baroque mythology of lodges, personified evil, and interdimensional rabbit holes.

The new season challenges us most in the way it seems to undo the story it is telling, moving out of sequence and perversely out of rhythm, indicating a wealth of paths it has no interest in going down, spending long stretches of time in scenes that do not immediately further the plot, and jumping without warning from characters and locales we know to those we don’t (and never come to know). The result is a feeling of erratic, transfixing chaos. A greasy drug-addled woman sits in the Roadhouse talking with her friend about zebras and penguins, scratching the “wicked rash” in her armpit. A woman frantically honking her horn screams at Deputy Briggs to let her car through traffic because, as she puts it with incredible and hideous fury, “We’re laaaaaate!” while a diseased young girl lurches from the passenger seat, vomiting a dark trickle of green slime. A young girl waiting for a friend at the Roadhouse is removed from her booth by two grown men, drops to her knees in the middle of a concert, and crawls through the crowd of dancers before screaming at the top of her lungs. In any other series — even the original series of Twin Peaks — these scenes would have consequences: they’d be explained or taken up again or at least referred to in passing later on, in order incorporate them into the larger plot. In Lynch’s hands, they are left only as refractory trace variations of the show’s central action.

It is as though Twin Peaks: The Return takes place in a world where different versions of the same story are played out on an endless loop, performed by an often anonymous cast of characters whose lives only occasionally intersect, but whose absurdities and traumas never cease to echo each other in new, uncanny permutations. It is the world we know, but the names and the faces are wrong. More strangely, this feeling of something being wrong is the only compass, the only coordinates we have.

¤

The notion of “late style” was first formulated by the philosopher Theodor Adorno to characterize the odd traits he observed in Beethoven’s late quartets. For Adorno, these works lack the same rigorous formal harmony of the composer’s mature music. In these pieces, Adorno says, “one finds formulas and phrases of convention scattered about,” musical tropes and clichés that appear “in a form that is bald, undisguised, untransformed.” Beethoven’s late music is tasteless in places, less fully integrated than it had been in the composer’s mature period, but it is also more open to formal discord: it is a music of “caesuras and sudden discontinuities,” a “catching fire between extremes” that militates against formal harmony.

We might suppose that this destructive spirit stems from the fact that the aging artist, closer to death, no longer cares what the public thinks and is free to express a more personal, uncompromising vision. Adorno finds this notion overly sentimental. For him, late works are born from the awareness that our subjective relationship to death can never enter artworks, which survive too long to record this mortifying knowledge. For this reason, late style is the result of an artist who has abandoned the very conceit of expression itself. As Adorno puts it in his inimitable manner, this mortified subjectivity creates works while also

break[ing] their bonds, not in order to express itself, but in order, expressionless, to cast off the appearance of art. Of the works themselves it leaves only fragments behind, and communicates itself, like a cipher, only through the blank spaces from which it has disengaged itself. Touched by death, the hand of the master sets free the masses of material that he used to form; its tears and fissures, witnesses to the finite powerlessness of the I confronted with Being, are its final work.

The comparison between Beethoven and Lynch is hardly exact. Having never really been a filmmaker too concerned with harmony, Lynch’s turn to a more formally dissonant late style might be seen as a simple intensification of his aesthetic. David Nevins of Showtime advanced something like this thesis when, in a pre-release promotional appearance, he called Twin Peaks: The Return “the pure heroin version of David Lynch.” But this hardly begins to describe the irresolute, scattershot tone of the new series, with its wonderfully awkward misfires and only intermittent attempts at flattering or satisfying its audience. No “pure heroin” version of the Lynchian psychopath — of the Frank Booth or Mr. Eddy variety — would ever have engaged in such an amazingly silly arm wrestling contest as does our evil Mr. C.

What the concept of “late style” allows us to see in the new Twin Peaks is the sense in which the show’s unresolved, intransigent style stems from a feeling of disappointment with the notion of the well-made work of art. Instead of the nostalgic recreation of a familiar form, Lynch gives us broken bits of what we loved, collaged together in surprising, often baffling ways. The series rejects smooth pacing, narrative efficiency, and well-defined character arcs. Plot threads are introduced and abandoned seemingly at will. Unexplained gaps in the story are the norm. The show plays inconsistent games with chronology, running roughshod over narrative continuity. It taunts its audience with gratuitous, overly specific references to characters we never meet (“Remember that guy, Sammy?” remarks Hutch at one point, apropos of nothing. “He passed away. Good guy.”) When The Return does offer us a classical, almost Aristotelian scene of resolution (with all the characters from the season’s various strands congregated into a single room), Lynch shows us just how unreal and unsatisfying such narrative resolution can feel: I speak, ahem, of Freddy’s magic green gardening glove. There is a falseness, and no small element of wish fulfillment, to this presentation of evil bested with a final punch, a point that Lynch drives home by superimposing Cooper’s slow-motion face over the remainder of the scene.

Along the way, Lynch, no longer in any hurry to stun his audience with shocking or amusing developments in the plot, can linger in the alien glory of unproductive details: a distraught Candie whipping Rodney Mitchum in the face with her remote control in search of an elusive fly; the amazingly distorted choreography of continental charm performed by the “French Woman” as she leaves Gordon Cole’s room; the loud, nauseous chirping of a drunk man in a jail cell, his face eaten by tubes and sores; the long meditative sweeping of the floor of the Roadhouse, set to the tune of Booker T and the M.G.s’s “Green Onions.” The tension we feel at work in these moments comes from the need to recognize something, to perceive some pattern or clue that will connect us back to what we believe the story is. There are patterns, to be sure: Candie’s remote control, for example, anticipates the remote control that Dougie will pick up before turning on Sunset Boulevard; the employee at the Roadhouse sweeps up the dirt and peanut shells into a series of mounds that resemble the mound of dirt where the demon BOB left his blood-smeared message following the murder of Laura Palmer.

But the narrative function of such patterns has changed. In the old Twin Peaks, Cooper really did receive clues in his dreams; a talking bird, whose vet’s office was located above a convenience store, really was a witness to some of the violence; his memory of red drapes really did lead him to one of the crime scenes. In the new Twin Peaks, this feeling of being surrounded by clues and patterns and dream images has become an enveloping, compulsive principle. Narrative space is continually being warped, interrupted, bent in the suggestion that what we see has its real significance somewhere else, in its connection to another scene, in a buried echo of someone else’s story. Images and gestures, sounds and intonations are detached from the narrative flow, and assume an odd, expressionless character as the bearers of messages. My log has a message for you. My red chair has a message for you. The cracked door of this Nez Perce bathroom stall has a message for you. Even the lights reflected in the windows of a passing plane, as some of the show’s most avid fans discovered, were blinking in a form of Morse code. This relentless encryption of narrative information is a hallmark of a show which has always addressed itself to a devoted cult audience, who can be counted on to detect even the smallest clues. But in Twin Peaks: The Return, Lynch insists upon a form of watching that leads us endlessly back to the helpless fact of watching. Even the giant (sorry, the Fireman) has his own home theater.

¤

How did Twin Peaks become a show of such extravagant, far-flung discord? In its first incarnation, Lynch and co-creator Mark Frost crafted a series based in a small town in the Pacific Northwest, a community in the heavy, nostalgic sense of the word, “where a yellow light still means slow down, not speed up” (as Cooper puts it in the pilot episode of the original series). The characters all knew one another, or thought they did before they were caught in the bright fire of Laura Palmer’s murder and the interdimensional outrage it unleashed. Narratively speaking, the show’s eccentricities (and there were plenty) were held together by a single life and the mystery of a single death. Laura, as Twin Peaks has never stopped reminding us, was the one. James Hurley was the first to utter this phrase in the show’s pilot. Then, it meant that she was the love of James’s life, and that he was going to have trouble moving on after her death. But when Lynch repackaged the series for reruns in 1993, he had the Log Lady adapt James’s self-pitying lament into a metaphysical axiom: Twin Peaks, she says introducing the pilot, “is a story of many, but it begins with one. The one leading to the many is Laura Palmer. Laura is the one.”

It is bewildering just how seriously Lynch meant this statement, viewed in light of the new season’s suggestion that Laura is less an individual character than an etherized cosmic MacGuffin housed in a golden bauble symbolizing the struggle against evil. But before Laura’s ghost was sapped of her demons and her pain, and purified into a metaphysical principle of light, Laura being “the one” meant simply that the story of her death provided a backbone to the show’s many plots, a dorsal architecture of radiating grief and troubled sexuality. Her face, framed angelically in her prom photo, appeared over the credits of nearly every episode, as if it were a talisman.

Laura’s face is equally prominent in the opening credits of the new season — now a vague, free-floating mirage, half obscured by clouds — but her orienting role in the show’s narrative system is much more tenuous. It is true that Gordon Cole is slapped with an unexplained vision of Laura one night, opening the door of his hotel room to find two reversed mirror images of her face flown in straight from Lynch’s 1992 feature Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. This moment feels like it ought to be significant. But Gordon is just as clueless as to what to do or how to help her as Donna was when she opened the door in the original film, and promptly forgets what he saw. It is also true that later this same episode, the log lady delivers her message again, this time to Hawk. “In these days,” she intones, “the glow is dying. What will be in the darkness that remains? […] Watch and listen to the dream of time and space. It all comes out now flowing like a river. That which is and is not. Hawk, Laura is the one.”

Is Laura still the one? She is and she isn’t. She’s dead and yet she lives in Odessa, Texas, and perhaps in everyone. We see the echo of her bright angelic smile in the face of Amanda Seyfried’s Becky. We hear the echo of her rape in the words of Diane (or her tulpa) as she describes Mr. C’s assault on her: “He saw the fear in me, and … he smiled,” she says, holding up her spread fingers before her face just like Laura did, in the first episode of the new series, before it cracked open to reveal the boundless light inside. We even come to see Laura’s reflection in the hilariously ominous bags of Turkey Jerky that trigger Sarah Palmer’s breakdown in the liquor store (recall that Laura once warned James that she was “long gone, like the turkey in the corn […] gobble gobble”). This game of “find Laura” can be played endlessly in a series where her reflected image is at once everywhere and nowhere. But the strange reality is that, even as Twin Peaks has grown increasingly monistic in its cult of Laura, it has also given rise to a remarkably entropic, fragmentary universe and to an equally disjunctive narrative style.

This season also provides us with a far less happy metaphor for the relation of the one to the many: that of nuclear fission and the fission bomb. To force the one into the many is the nature of atomic violence, and some of the most unexpected visual abstractions from “Part 8” focus our attention on just this kind of destructive, fragmentary swarming. They are images of particles rushing like furious gnats against an indistinct gray background, and white flecks blurred and floating in a dark haze: the universe as a primal, aggressive frenzy.

Narratively speaking, too, the season obeys the atomic logic of splitting. There are now two Sheriff Trumans. There are at least three or four Dianes (including Naido, the chirping woman with eyes sewn shut), and even more Coopers. And the show’s unifying, iconic location has ballooned to at least six (even more if we count the lodges). To be sure, the scope of Twin Peaks has grown larger with the new season. But it also sometimes feels like a show disintegrating before our eyes, a once-whole fictional world cracking to bits. Lynch, like the practitioner of late style that Adorno describes, does not seek to bring about a “harmonious synthesis.” Drawing instead upon “the power of dissociation, he tears [both the subjective and objective elements of the artwork] apart in time, in order, perhaps, to preserve them for the eternal.”

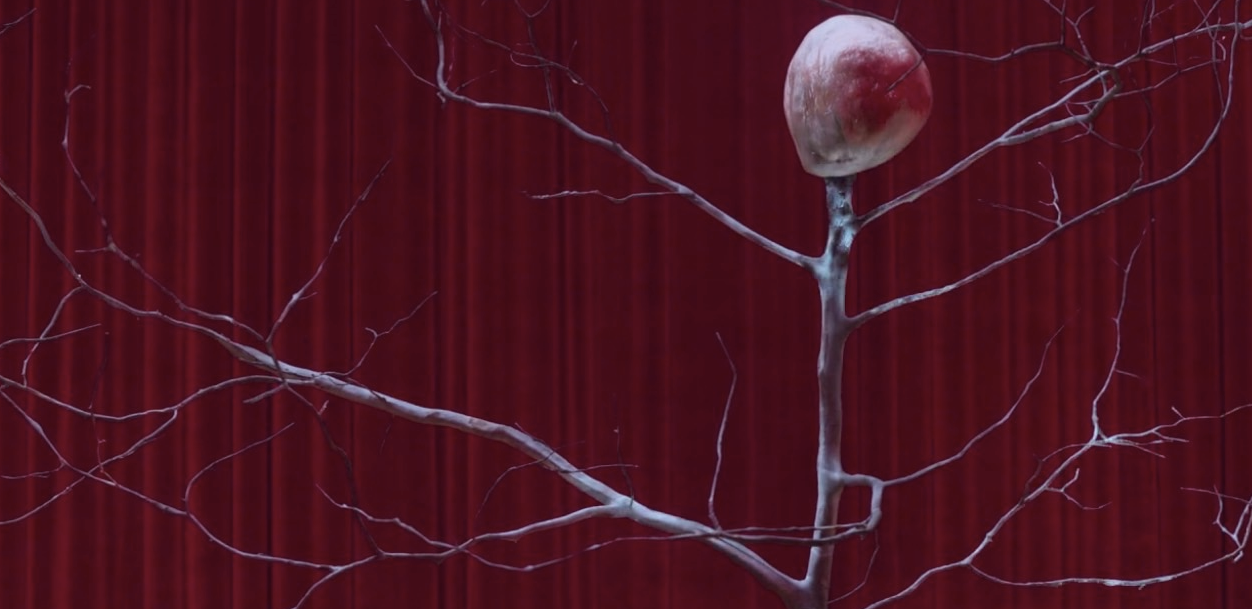

The late style of the new Twin Peaks is nowhere more evident than in the giddy profanation of its own aesthetic legacy, which openly trivializes the visceral power of the original show’s vast symbolic repertoire. The Return replaces the singular figure of the Man from Another Place with a blinking Charlie Brown Christmas tree topped with a quivering mound of flesh. Do you remember when the image of the Red Room inspired a kind of mystic awe? Now it floats and blinks above slot machines to guide Cooper in the form of slow-witted Dougie Jones. Do you remember the amorphous fear that struck you when you saw the One-Armed Man screaming at Laura Palmer from his car in Fire Walk With Me? Now he sends gentle reminders to Dougie from the cushions of household sofas. And what about BOB, the archvillain of the original series, with his hellish grimace and slow malevolent crawls toward the camera? Now his eternally smiling face subsists within a black jelly egg first birthed in a gray storm of demon vomit.

Yet these revisionist attacks on the surreal lyricism of the original series are so outrageous, and so unapologetic, that one cannot help but respect the sheer perversity of The Return’s gleefully committed sins against good taste. In this wholesale exchange of the sublime for the ridiculous, Lynch toys with the untimeliness of a fictional universe that can never return to what it was, and with the failure of all works of art to establish an enduring reality outside the reach of time.

¤

Even in very first episode of the original series, it was already too late for Laura Palmer. In its many incarnations, Twin Peaks has struggled with the inevitability of her death and the show’s dependence on the deranged logic that brought it about. In the network series, Lynch “resurrected” Laura in the character of Maddy Ferguson, Laura’s twin cousin, only to have a helpless Agent Cooper seem to watch her murder transpire in his vision across town at the Roadhouse. Brilliant as Cooper was in his understanding of the demonic dream logic of Laura’s killer, Lynch and Frost did not give us a hero capable of saving the day. In Fire Walk With Me, Lynch brought Laura back to life yet again, only to present the circumstances of her suffering in even more horrifying detail.

The ending of Twin Peaks: The Return offers a still more depressive reflection on this sense of narrative futility. In the penultimate episode of the new series, Cooper, after paying his respects to his en-tea-kettled colleague Phillip Jeffries, promptly scurries back in time to rescue Laura — for good this time, he thinks — leading her by the arm away from the fate that Twin Peaks had in store for her. Yet there is something profoundly melancholy about the digitally enhanced youthfulness of Sheryl Lee’s face in this scene, just as there is something grotesquely sad about many of the depthless post-production elements in the new season. Laura can be spared only in this made-up realm, without the brilliant humanity of Lee’s embodied performance. What reality do these characters or their stories have when detached from the faces and the lives of the actors who inhabited them so memorably? When Laura is “rescued” by Agent Cooper, Lynch allows the show’s fictional world to take leave of its former reality. In doing so, he sets Twin Peaks free by destroying it, creating a timeline in which the series as we knew it never happened.

Lynch knows that the world has moved on from Twin Peaks, and that many of the actors from Twin Peaks have moved on from the world. His camera is most eloquent when it is calling our attention to the lines on the faces of the show’s aging cast, a startling number of whom (including Catherine Coulson, Miguel Ferrer, Warren Frost, Harry Dean Stanton, and, most recently, Brent Briscoe) have died since the season finished shooting, and when reminding us of the actors from the original run who were no longer alive to reprise their roles (Frank Silva, Don S. Davis, David Bowie). In the penultimate episode, for instance, Pete Martell goes out to fish that morning, just as in the series pilot, only this time without stumbling on Laura’s corpse. But the great Jack Nance, who played Pete in the original series and to whom this episode is dedicated, has already been dead for two decades. In the face of real death, can it matter to us, or to Lynch, if “Pete” lives on? Or if “Laura” survives? Once art has relinquished any claim on our lived reality, can we continue to care about its characters? What kind of grotesque survival is this that can only be lived inside a dream?

Lynch’s late style, in all its formal strangeness and occasional ugliness, is a way of posing these questions. For him, as for Adorno, the very premise of art’s formal harmony stands in the way of our knowledge of death. “Death is imposed only on created beings,” Adorno tells us, “not on works of art, and thus it has appeared in art only in a refracted mode, as allegory.” Twin Peaks: The Return is perhaps best understood as a carnivalesque anthology of such refracted allegories, meditations on its own untimeliness.

Remember the puckered face of Jack, the mechanic? Like most of the images in Twin Peaks, it has its doppelgänger version as well. Late in “Part 11,” Dougie is being led out to a limo that will take him to meet the Mitchum brothers. His boss, the ex-boxer Bushnell Mullins, delivers a tender jab to Dougie’s jaw and wishes him well in the meeting. “Knock ’em dead, champ,” he says. In his slow, characteristically faded way, Dougie feels the touch that Bushnell has given him and reaches up to hold his own cheeks in his hand. We watch him slowly move his skin back and forth, as he gives his now predictable reply, echoing whatever has just been said. When he speaks we have the dim sense that it is just his skin that is talking. The word it says is “dead.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Jonathan Foltz is an assistant professor at Boston University, where he teaches modernist literature and film. His writing has appeared in Modernism/modernity, Screen, and Not Coming to a Theater Near You. He is the author of The Novel After Film, forthcoming from Oxford University Press.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Return of the Naïve Genius: “David Lynch: The Art Life” and “Twin Peaks: The Return”

Reading any interview with Lynch since the release of "Eraserhead" leaves open the question of whether the director performs his innocent remoteness.

Variety Show

Does "Twin Peaks: The Return" matter?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!