Conduits to a Feeling: On Sophia Giovannitti’s “Working Girl”

Ayden LeRoux reviews Sophia Giovannitti’s “Working Girl: On Selling Art and Selling Sex.”

By Ayden LeRouxNovember 3, 2023

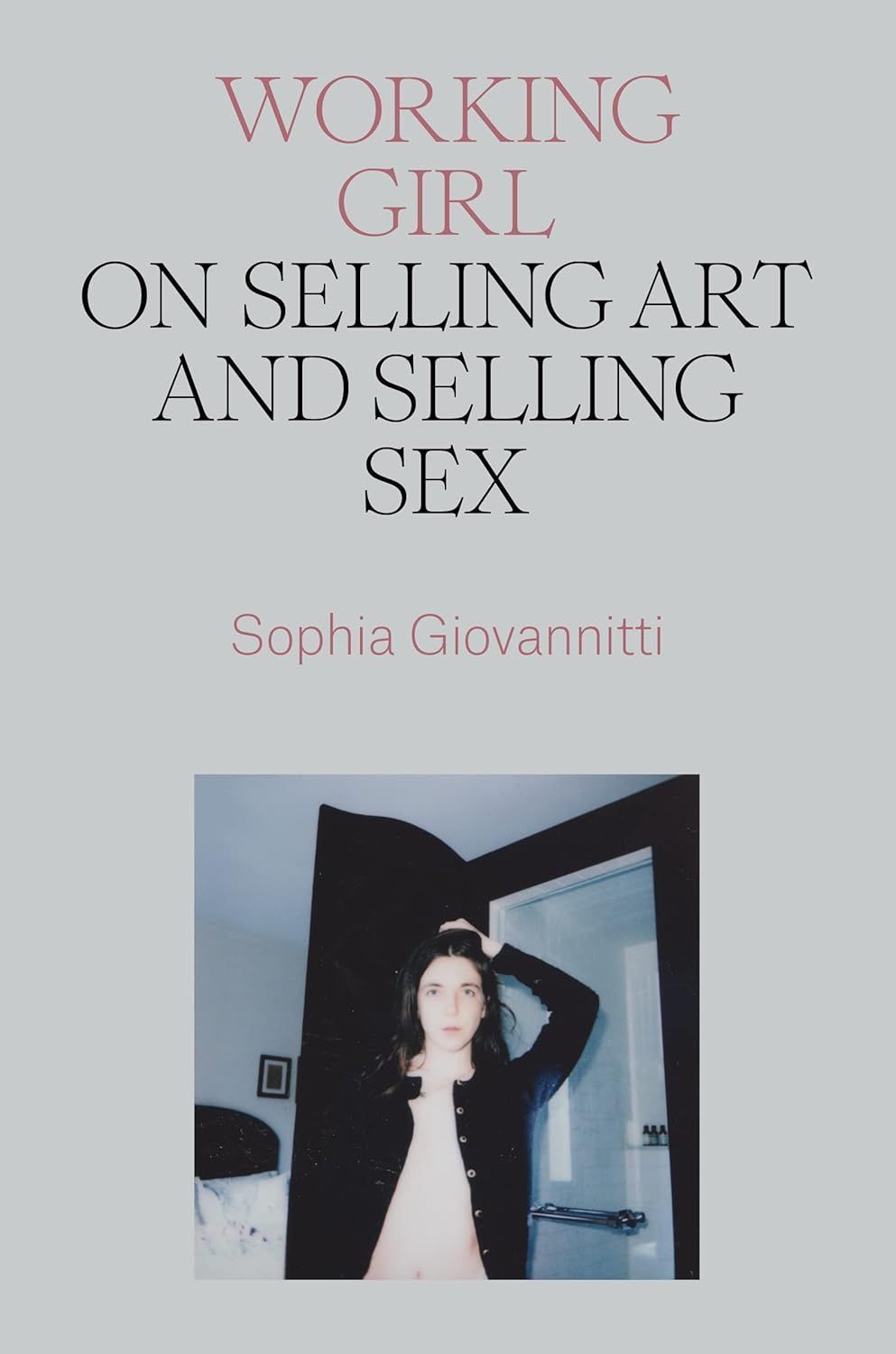

Working Girl: On Selling Art and Selling Sex by Sophia Giovannitti. Verso. 192 pages.

THE FIRST TIME I ever met a sex worker, or at least someone who I knew was such, was the first time I hitchhiked. It took me two hours to catch a ride. When someone at the gate of the hot spring finally stopped, I remember feeling relieved that I wasn’t being picked up by a man. The driver, who I’ll call Lucy, was older than me. Her exact age was hard to pinpoint; she had a full head of silver hair that framed a face with smooth, youthful skin.

I doubt Lucy planned to reveal this part of her work life to me. I doubt she regularly revealed it to strangers, but she inquired about what I did, and we started talking about art. I told her about the nature of the art I make with Odyssey Works, a group that studies the life of one individual for six months to create a performance for them that is interwoven with their life. The pieces usually last about a weekend. Often, they don’t feel like performances at all. They’re life, but more serendipitous and more consciously crafted: perhaps a radio show about the very subject you have been fascinated with lately comes on, or 50 strangers spontaneously gather to throw messages in bottles off a pier while you yourself release a letter saying goodbye to a mentor. Friends and family participate as friends and family. Actors enmesh themselves into structured scenes in the life of the chosen participant. They aren’t so much acting, though, as aiming to find intersections between their own thematic inquiries about, say, grief or community, and those of the participant. Chance can play a role too. No matter what, within the concentrated and attentive frame of the performance, meaning takes on a denser, deeper quality.

As I described my work to Lucy, our conversation turned to the economic side of things. She wanted to know how the performances are funded. Everyone does. They’re supported by grants, public funding, or crowdfunding. We try to protect the work from becoming an exchange of services by making it a gift for the participant, entirely free. Otherwise, the recipient would become a client—making the performances more transactional in nature and deemphasizing the potential for an open-ended, transformative experience. These two qualities are vital: in the weeks and months following a performance, most participants undergo major life transitions. They change their jobs, move, commit to or leave a loved one—not because we directly compel them to, but because they look at things differently after the Odyssey. How can they not, when every moment has assumed more weight?

Lucy shared that she did work she felt was quite similar: having sex for money with people she met on Craigslist. She and a potential client would have a coffee date and she would decide if she felt safe around them. If she did, she’d try to understand what they most needed and, from there, create an erotic, intimate experience. Unlike many stereotypes of sex workers, Lucy was not broke and did not seem disenfranchised in any apparent way. In fact, she had another business. She simply said she liked sex work, was very good at it, and was turned on by the exchange of money. We marveled at how both of us made bespoke, uncannily intimate performances for an audience of one. What each of us offered (for me, art, and for her, sexual experiences) often converged in their result: people were seen and known in uncommon ways. The chief difference was where and how money entered the equation.

Similar themes and forces—performance art, sex, and capitalism—are central to Sophia Giovannitti’s magnetic and erudite book Working Girl (2023). Giovannitti’s first book-length publication, the work of autotheory probes the entanglement of the author’s experiences selling art and sex. Mapping how the two operate within capitalistic frameworks generates obvious yet rich comparisons: both art and sex are concerned with beauty, seduction, value, fantasy, meaning, power, and—at moments—the sacred. They hover in a territory where commodification is nearly taboo, making it easy for their sale to topple quickly into exploitation and deception.

How value is created, distorted, and extracted forms a point of fascination for Giovannitti. The writer admits early in the book that when she first stepped into sex work, she “wanted to sell a performance, not sex.” This mental maneuver to distinguish what she was about to embark on as art rather than prostitution is entirely understandable, given how porous the definitions of art and sex are. And with so much stigma and risk associated with sex work, who wouldn’t want to categorically circumvent those and call what they do art? For a certain sort of sex worker—especially one dually interested in the cerebral and the carnal—why not proclaim her work as something useful, in service of the other components of her identity?

Giovannitti has a masterful ability to describe encounters with clients while simultaneously skewing away from the salacious in Working Girl. Of course, she inevitably reveals some of the gristliest joints of sex, power, money, and meaning. Her writing attends to the moments when reality and the role she assumes collide—when authenticity and performance choke one another. In one scene, she describes seeing a client whose mother died earlier in the day. During a scene where he teaches a group of sex workers pretending to be virgins how to touch his penis, he answers a phone call from his actual child and comforts them. Giovannitti marvels that he has not canceled the appointment, that he allows real life to puncture the scene. This fantasy must be a vital distraction, and she notes that she feels softer to him than on previous occasions.

This interplay between “real life” and the adjacent realities of performed scenes are additionally complexified by Giovannitti’s awareness that her identity as an artist represents part of her appeal to many of her clients. We watch her wriggle through a paradoxical tangle of authenticity and artifice as her real identity and her roles within sex work collide. In one scene, the writer relates abruptly interrupting an evening at a hotel with a client when she realizes it is the deadline for an artist residency. She scrambles to submit her application on her phone from the room they share. She has broken the fourth wall; still, she knows that he can’t complain. If he did, he would be breaking it as well, and, with that, the fantasy that she was his girlfriend would crumble. Giovannitti knows that many of her clients fetishize the idea that they are helping to cultivate her career, that her real identity as an artist (though perhaps not her real self) provides an important scaffold for their fantasies. Money is not the only thing exchanged—many of those to whom she provides services also offer art-world and media connections in return.

Discussing this dynamic, Giovannitti highlights the nuances and near-constancies of mutual imbrication: we all make transactions, exchanges, and trades with our bodies every day. In my early twenties, several other sex workers became friends and acquaintances of mine. Through our conversations, I came to recognize the daily ways in which my body was used transactionally. My friends often described providing nurturing, caring spaces for their clients; I was paid to provide warmth, care, and safety too. The nature of my services was maternal rather than sexual, of course, yet I could see how the distinct emotional texture I offered was at once genuine and part of the transaction. Just as Giovannitti relates experiencing real attraction to some clients, I felt real care for the children I watched. And, like Giovannitti, my concurrent identity as a young artist and writer was appealing to the family I worked for.

Working Girl is most thrilling in its examination of the slippages between persona and identity—the moments when the artist self surfaces within Giovannitti’s sex work. Early in the book, Giovannitti describes her initial attempts to compartmentalize her identity by creating personas for sex work or writing about sex work under pseudonyms. These were, she admits, weaker performances. When she eventually allowed herself to be known as Sophia, her clients continued to see her at higher rates. “I will always answer more warmly—more truly—to my own name,” she says, and though she is certainly still performing when she uses her real name, it’s easy to imagine that this gesture would feel more authentic to many of her clients. Herein lies a crucial difference between a person who is selling a performance and a body that is being sold. On the very first page of Working Girl, Giovannitti writes, “Making art can justify a recklessness that making money doesn’t.” This recklessness and teeming sense of abandon (freedom, even) is immensely seductive. After all, art and sex are deeply permissive spaces where we can exert pressure on what is real and performed, where playing a role or being exactly ourselves can both be liberatory in equal measure.

Capitalism plays the (predictable) villain in this book. Of course, Giovannitti is far from the first to exert pressure on art-world corruption. Public discourse has become saturated with critiques of it in recent years, spawning a new cadre of ways to resist and then ways that resistance seems to curdle. “Self-care,” once a rallying cry to slow down, is now a term thinned out by use and deployed by marketing companies to sell more products. Regrettably, Jenny Odell’s book How to Do Nothing; Resisting the Attention Economy (2019) has become shorthand for many of my students to do less in general (rather than just for the institutions and industries that exploit them; education, after all, asks us to work hard for our betterment and growth). For many, the nuanced argument to do less in favor of observing the world closely, slowly, and with intention is lost.

Amid this often convoluted conversation, Lewis Hyde’s The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property (1983) offers a helpful dissection of labor and work. Work is done by the hour and for money. Labor, on the other hand, is something that may include payment but is notably difficult to quantify. “[L]abor has its own schedule […] sets its own pace, is usually accompanied by idleness, leisure, even sleep,” writes Hyde. He adds that labor is “dictated by the course of life rather than by society, something that is often urgent […] something more bound up with feeling […] than work.” By this definition, devotion to one’s labor becomes alchemical in creating meaning. After all, while good art, good relationships, and good sex can all feel effortless, they are typically produced from the fecundity of effort, study, failure, friction, devotion, and slow and steady attention. Giovannitti’s determination to do as little work as possible for as much money as possible—so that she can be at liberty to undertake the labor of making art and reading and loving her boyfriend and caring for her community—resonates with the psychic concerns of our age.

Working Girl is evidence of the riches these efforts yield. Readers will find infinite pleasure in surrendering to Giovannitti’s labor-won intelligence. Her disdain for work and capitalism shimmer, as she emphasizes the profundity of her devotion to art. She interrogates feminist anxieties about consent and the disempowerment of women and genderqueer people in sex work; she observes how her education and whiteness comfort clients who need assurance that she has agency in choosing this work.

Situating such salient critiques of capitalism alongside professions of her reverence for art and devotion to beauty, Giovannitti casts both sex and art as “conduit[s] to a feeling”—to elevated states. She doesn’t ignore the attendant religiosity of the two, nor does she shy away from pushing viewers to reimagine what constitutes the profane. She describes making a series of self-portraits titled Exalted, which are close-ups of her face right before and after her boyfriend cums on it. To her, this moment is ecstatic, heavenly, holy—and, while certainly there will never be a consensus on any particular sex act being revelatory, to observe these images is to appreciate the transcendent possibilities and pleasures of sex. Here, Giovannitti’s writing and rigor prove most stirring: amid the sharp and insightful lens on capitalism and the machinations of the art market, she is still unabashedly interested in the twin engines of beauty and desire. These forces fuel art and sex’s profound potential to move us. Where rage could take over, Giovannitti also gives us reverence.

¤

LARB Contributor

Ayden LeRoux is an artist, writer, and critic whose work explores embodiment, eroticism, and illness, in order to complicate narratives about gender, sexuality, and family structures. Her work has appeared in BOMB, Bookforum, Catapult, Electric Lit, Entropy, Guernica, Lit Hub, Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Rumpus, and was honored as Notable in Best American Essays 2021. She is the author of Isolation & Amazement (Samsara Press, 2013) and Odyssey Works (Princeton Architectural Press, 2016).

LARB Staff Recommendations

When Reality Isn’t: On Nathan Fielder’s “The Rehearsal”

Israel Daramola reviews Nathan Fielder’s “The Rehearsal.”

John Waters on Filmmaking, Felonies, Fox News, and Fucking

Conor Williams gawks at “Liarmouth: A Feel-Bad Romance” by John Waters.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!