John Waters on Filmmaking, Felonies, Fox News, and Fucking

Conor Williams gawks at “Liarmouth: A Feel-Bad Romance” by John Waters.

By Conor WilliamsAugust 31, 2022

Liarmouth: A Feel-Bad Romance by John Waters. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 256 pages.

IN 1970, A LONG-HAIRED freak from Baltimore armed with a camera and a coterie of pot-smoking ne’er-do-wells set out upon filming a grotesque experiment called Multiple Maniacs. The film details the exploits of one Divine and her carny crew’s traveling sideshow, “The Cavalcade of Perversions,” a performance that routinely ends with a grand finale of mass robbery. Within his backyard and a budget of $5,000, writer-director John Waters and his Dreamland troupe devised a nightmare that shocked the world. A filthy church-set sex scene features the unholy anal insertion of rosary beads, and the film’s out-of-nowhere climax comes when Divine is raped by a giant lobster. In 2017, The Criterion Collection, the prestigious video distributor many consider an arbiter of the cinematic canon, unleashed a newly restored Maniacs upon a new generation. Since then, Criterion has released Waters’s Female Trouble (1974) and Polyester (1981), and, marking Pride Month and 50 years since the film came out, they’ve released his opus, Pink Flamingos (1972).

While his filmography is now iconic — his mainstream hit Hairspray (1988) has spawned both a remake and an acclaimed musical — the 76-year-old provocateur hasn’t made a picture since 2004. Waters has instead occupied himself with other projects, namely fine art and writing. His more recent books include Carsick: John Waters Hitchhikes Across America (2014) and Mr. Know-It-All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder (2019). The so-called “filth elder” has now written his first novel, Liarmouth: A Feel-Bad Romance, released this May by Macmillan Publishers.

To celebrate this latest endeavor, Waters speaks with me over the phone from his getaway in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Winding down to the end of a whirlwind press tour, he sounds relaxed. Provincetown, after all, has become something of another home to him over the years, his first home being, famously, the city of Baltimore. He speaks softly, but his voice retains its charismatic warmth. (Due to a bad cell connection, we strain at times to hear each other. When I ask if he’s seen Julia Ducournau’s 2021 body-horror hit Titane, he responds matter-of-factly: “Yes, I’ve seen Titanic.”) I had previously met him in person, at an event where, for COVID-19 precautions, he sat behind a thin barrier of plexiglass. It felt sort of like I was visiting him in prison. Over the phone, I ask Waters if he’s ever been arrested. “I was arrested for lots of things,” Waters tells me casually. “But I was never sentenced for anything.”

My mind flashes to Jonas Mekas’s 1964 reportage on getting arrested for screening Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963) — which could’ve been the title of a Waters film — and further provoking the police by showing Un Chant d’amour (1950), the sole film by queer author Jean Genet, who wrote one of his books while he was imprisoned. I knew Waters had read Mekas’s Film Culture magazine. Was this the cinematic tradition of transgression he hoped to evoke as a young filmmaker?

Oh, definitely. I think Jonas Mekas was my first influence. I would get the Village Voice in Baltimore, and I had a subscription when I was really young. His “Movie Journal” column was something that I read all the time. Right before he died, he gave me an original flier for Warhol’s Empire, which he actually shot. We became friends, and he was definitely a giant influence on me. He only liked underground movies.

I tell Waters that, before our phone call, I started my morning with a 10:55 a.m. screening of Criterion’s restoration of Pink Flamingos at IFC Center. “Good lord. Was it just you?” “Me and two other people,” I say.

I don’t think Pink Flamingos has ever played at 10:55 a.m. We just had two sold-out screenings the other night. It was so amazing because the audience was so young. They asked the audience: raise your hand if it’s your first time seeing Pink Flamingos. A large number raised their hands, which is kind of amazing and great. This was the first time where at the meet-and-greet afterwards, there were 20-year-olds asking me to sign Pasolini books.

Pier Paolo Pasolini, an Italian, Catholic, Marxist, gay filmmaker, was celebrated throughout his career, but stirred immense controversy with his final work, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975). Salò was an indictment of fascism, depicting the depraved and barbarous pastimes of the wealthy elite: humiliation, rape, and several servings of feces.

Pasolini’s themes were a definite influence on Waters, although his own cinematic grenade, Pink Flamingos, predates Salò by a few years. (A poster for Pasolini’s 1968 film Teorema can actually be seen in some brief moments of Flamingos.) And while Pasolini used chocolate for his scatological gross-out scenes, Waters had Divine chow down on real dog shit. Last year, Waters made a pilgrimage to the site of Pasolini’s assassination at the hands of a 17-year-old hustler. While on sacred ground, he recorded a prayer to the late artist, eulogizing the man “who was conceived by Marx, born of the future spirit of Maria Callas, suffered under the Catholic Church, was assassinated and buried unguilty.” Waters ended his prayer by promising that Pasolini shall “come to judge the censors, the fascists, and the fag bashers.” Thinking back on that trip, Waters tells me: “Where he was murdered, there’s this secret little beautiful park. It looks like it’s locked, but it really isn’t. It was kind of spooky and beautiful. I spoke in tongues there. And he’s answered my prayers,” Waters rejoices. “My life’s been pretty good lately!”

Looking back on Pink Flamingos, he sighs:

It was the hardest movie to make. What pros everybody was. They worked 20 hours outside with no heat and no food. Memorizing pages of dialogue without any cuts. Most of my memories are about how hard it was. Even watching it, you see Edith [Massey] sitting in that playpen and you can see her breath because it was so cold out. I remember how brave everybody was to make it. The courage it took to be that crazy. I was trying to make exploitation films for art cinemas. Really, I was trying to make films that would be funny to my friends and the film buffs I knew, so I had to make a movie that seemed like nothing else.

Given that it’s been some time now since his last feature film, I ask Waters if he’s faced any trouble in making movies these days.

Not really. I had three different sequels to Hairspray which I was paid big Hollywood money to write. One a musical, one a TV show, and one a TV movie. They never got made, and I had a children’s special that was developed a long time ago. But I never talk about something while I’m in the middle of it — otherwise, it aborts. And that’s the only kind of abortion I’m against.

That said, the landscape of independent cinema, according to Waters, is “pretty scary, because the people who didn’t come back to the theaters are people older than 50, and they were the bread and butter of art cinema.”

From the rosary job in Multiple Maniacs, to Divine playing both participants in a filthy roadside fuck in Female Trouble, to penetration via chicken in Pink Flamingos, Waters’s films are chock-full of sexual debauchery. I elicit his take on a recent opinion, seemingly held among a younger, online generation, that sex scenes in films are unnecessary. Waters scoffs: “I haven’t heard that one. That’s a good one. Young people don’t want to see sex in movies? Jesus Christ.” He mentions that Deep Throat (1972) just screened at Roxy Cinema, referencing Andrea Dworkin’s takeaway from the film: “Any woman that had a penis that far down her throat could never tell the truth.”

“I’m all for nudity in a movie if it’s good nudity and it helps the movie creatively,” Waters continues.

Gratuitous nudity these days … What happened to feminism? When you watch all these awards shows, why are all these women nude? You should make them pay for that, not give it away on the red carpet! Brad Pitt doesn’t show his balls! But maybe he should.

“Would you be fine if you never heard the word ‘camp’ again?” I ask. Waters thinks the term has lost its relevance: “I haven’t said that word out loud since 1966.” As for whether he’s seen any movies recently that remind him of his early work,

I don’t think anybody copies me, but Harmony Korine, Todd Solondz, Bruno Dumont, Gaspar Noé, I like those kinds of directors. They’re sometimes not funny at all. They’re very serious and eerily melodramatic. I just like movies that surprise me.

Having always loved David Cronenberg, he tells me, he’s dying to see the auteur’s latest film, Crimes of the Future (2022). Waters also praises David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: The Return (2017): “I especially loved the whole episode that took place within the blast of an explosion. I thought it was the ultimate art film.”

Lynch apparently sponsored Waters’s entry into the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The Academy’s new museum will be hosting an exhibition dedicated to Waters next year.

I’ve kept that secret for two years. They’ve been going through my film archive at Wesleyan University; they have this huge collection. I didn’t even remember what they had! I found stuff I didn’t even know about. They call all the people that were in the movies and see what collections they have … This has been going on for two years now. It’s a major production. I’m really excited. Over the moon!

On top of that, he is receiving the overdue honor of a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Amidst all the fanfare, Waters still has the ability to shock and surprise even his most ardent disciples. He recently appeared on Fox News’s attempt at a late-night comedy show, Gutfeld! The humor of Gutfeld! is imperceptible. With a half-paralyzed put-on smirk, Greg Gutfeld delivers lines to a drizzle of forced laughs, although what he says is more often than not met with silent confusion from his studio audience. The subject of Waters’s episode was remote learning and the well-being of children. Waters, imagining how he’d be as a schoolteacher, cracked to Gutfeld: “I’d be controversial and introduce a ‘Don’t Say Straight’ campaign where they can’t talk about plumber’s crack, missionary position, line dancing, or the state of Florida.” Why would John Waters go on the nation’s pro-putsch propaganda network?

I love to go into enemy territory. They treated me fine! It’s show business. I’ve done Fox News before. I don’t agree with a lot of them, but so what? That’s the point. I’m not a separatist. You have to be able to joke with both sides and find new audiences. Otherwise, only people exactly like you will know about your work.

As someone who sees Waters as almost a godfather figure, I’m certainly not out to cancel the Pope of Trash. Still, I’m frustrated by his dismissal here. Last year, Waters appeared at an event infamously dubbed the “Anti-Woke Film Festival,” reportedly funded by PayPal co-founder and real-life fascist vampire Peter Thiel. At the festival, Waters spoke with Anna Khachiyan and Dasha Nekrasova, the try-hard edgelord hosts of the popular podcast Red Scare. While it’s likely that Waters simply saw this as a chance to celebrate the rabble-rousers of today, the fact is that the Red Scare hosts have buddied up to people like Alex Jones and Steve Bannon. Waters may think he’s just playing around — after all, his satire has always targeted the sensitive bourgeois — but the figures he’s appearing alongside are reactionary conservatives posing as post-left provocateurs, using his iconic status to boost their troubling cause.

By his own account, when a long-haired Waters was starting out in cinema in the 1970s, he was more aligned with Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies than the hippies. Pasolini, meanwhile, recognized the slippery nature of ideology, writing an essay in 1973 personifying the hippie hairstyle and warning of its dangerous possibilities:

I have also been adopted by the fascist provocateurs who have blended with the verbal revolutionaries […] My chaotic flowing tends to make every face similar […] In fact, a right-wing subculture can easily be confused with a leftist subculture. So I understood that the language of the long hair was no longer expressing “leftist things” but instead something quite equivocal, a Right-Left, that was making the presence of the provocateurs possible.

Despite Pasolini’s prescience, Waters doesn’t seem too worried. When I tell him about the conservative push to label queer people “groomers,” he asks,

What’s that mean, like “we’re out to recruit you”? It seems to me that whatever the right wing says today, whenever they go after someone, it only strengthens our cause. Anita Bryant was actually, in the long run, good for gay causes because she made people angry and brought people together to fight bigotry.

But as for the word “groomer,” he suggests: “Well, we call straight people ‘breeders.’ That’s kinda rude.” Touché, John.

Our attention turns to Liarmouth. Regarding his writing process, Waters confesses, “I wish I could just go in with a tape recorder and sit there and say, chapter one, and do it that way. I think Jack Kerouac did that, but I can’t do that. I just keep writing every day.” Writing every day, and apparently, as Waters divulges, by hand:

I really know how to handwrite. They don’t even teach it in schools anymore. I need to feel the actual writing. My handwriting is very Cy Twombly–ish, but my assistants have learned how to read it. They type it up and then I cut it up again, and then I read it into a tape recorder so they can type it.

Detailing the differences in his prose and screenwriting processes, he explains:

Writing for the page, you can go into more details about the characters and what they’re feeling. To me, it was new, but it wasn’t that different, because I’ve written so many movies. I wanted the style to be just like I was sitting down and telling you a story in person. I wanted you to almost hear my voice. And that takes a lot of drafts!

However many drafts it took, Waters’s persistence pays off, as his voice comes through onto the page unmistakably. Who else could conceive of the novel’s antiheroine, Marsha Sprinkle, a conceited thief whose preferred loot of choice is other people’s airplane luggage, or her trampoline-obsessed daughter Poppy? Marsha is aided by her getaway driver Daryl, rewarding him with a single sexual tryst one day a year. Unfortunately for Daryl, Waters later bestows his penis with a sentience that betrays its owner’s sexual preferences: yes, a penis with a mind of its own. That’s in the book, along with a guy who masturbates to The Simpsons — “Marge, to be specific,” the novel makes a point to clarify — and one who gets off on tickling.

Waters warns me that the thievery he writes about in Liarmouth could really happen. He actually points this out in the book, writing: “They don’t even bother to have a security guard outside each baggage-claim area matching the bags to your boarding pass sticker the way they did in the old days.” I ask Waters if he’s ever had something stolen from him. “Yeah, from my hand-checked luggage. My La Mer cream. But I’ve never had my suitcase stolen!”

Missing luxury skin care products be damned, Waters never passes up an opportunity to look good. I passed a store window in Manhattan the other day where he and his collaborator Mink Stole starred in a Calvin Klein ad. “John Waters and Mink Stole are family,” it read. “This is Love.” It’s surprisingly wholesome. In one part of Liarmouth, Waters lampoons the corporatization of social progress by imagining the futures of made-up trans sex workers:

Old Carrot Bottom. Ah, there was a gal. Got the surgery and now she’s the manager of a Trader Joe’s. And Feral Street, God, what a bod, what a rod! Bunch of do-gooders from a group called Baltimore Safe House “rescued” her and helped her start anew, off the streets. Guess where she works now? H&R Block, right up the street. And they know! And don’t care! It’s normal now! What’s the world coming to?!

Although capitalist Pride ploys usually make my stomach churn, the Calvin Klein ad was at least bold enough to offer a queer imagining of a nuclear family. To an unsuspecting passerby, Waters and Stole might very well appear to be husband and wife. Waters says his Dreamland troupe was his chosen family. “We’re even getting buried together, where Divine is buried.”

It’s a poignant idea, the thought of John Waters and his crew in a postmortem family reunion. One can imagine a fan falling to his knees in reverence, as Waters did, at a quaint site marking the life and legacy of cinema’s most perverse auteur. Flowers and cards left in memoriam. Green grass dotted with dog shit. Thankfully, such a scene seems to be far off. John Waters has been hard at work, always trying something new. He isn’t slowing down or shutting up any time soon, steadfast in his determination to make the world a filthier place.

¤

Conor Williams is a filmmaker and critic from New York.

¤

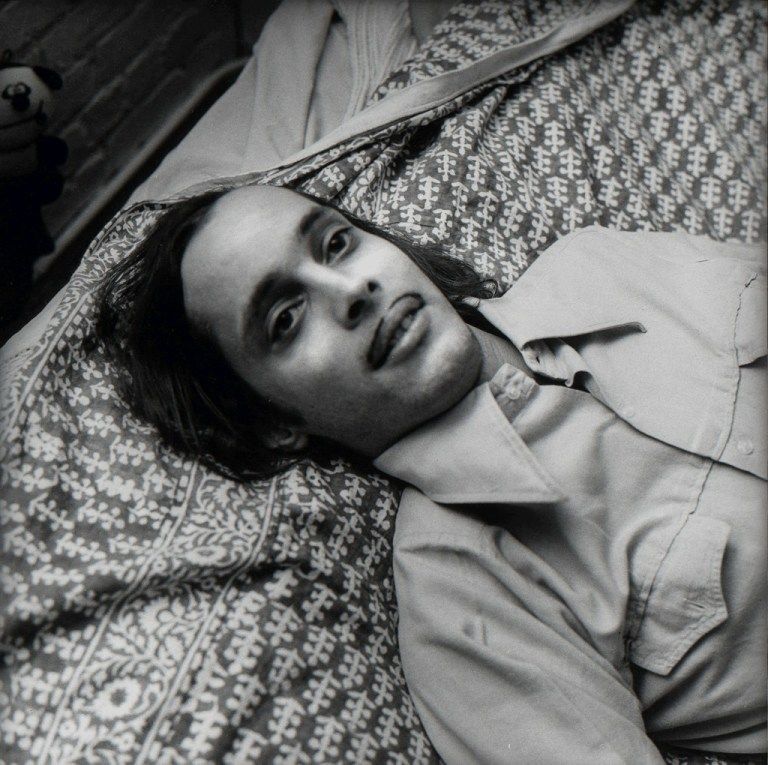

Author photo: John Waters (III) by Peter Hujar, c. 1975.

LARB Contributor

Conor Williams is a filmmaker and writer who has contributed to Interview Magazine, BOMB, and elsewhere. He currently works at BAM Rose Cinemas.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Benefiting from the Unfairness”: On Lisa Taddeo’s “Ghost Lover”

Elizabeth Barber reviews Lisa Taddeo’s new collection of stories, “Ghost Lover.”

The Eternal Exile: On Jonas Mekas’s Cinema of Memory and Displacement

Dante A. Ciampaglia looks back over the long career of avant-garde film pioneer Jonas Mekas.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!