“Art Is So Scary”: Yulia Tsvetkova and the Suppression of Dissent in Putin’s Russia

Lillian Avedian examines the campaign of persecution against an outspoken Russian artist and activist.

By Lillian AvedianNovember 18, 2020

AT SIX O’CLOCK in the morning on November 20, 2019, Yulia Tsvetkova arrived at the train station of her hometown Komsomolsk-on-Amur, in far eastern Russia, where her mother was waiting to welcome her after her travels. Instead of driving home with her mother as expected, Tsvetkova was met by law enforcement officials who took her to the police station, where they informed her that criminal charges were being pressed against her. Two days later, she was placed under house arrest on accusations of illegally disseminating homosexual propaganda through her art. Thus began a months-long nightmare of detainment, intimidation, illegal searches, lengthy interrogations, and creative censorship.

The 27-year-old artist has been a painter and illustrator her entire life, yet three years ago she embarked on the path of becoming an activist, empowering herself and her community through her art. “The art that I was doing had to do a lot with my personal liberation,” Tsvetkova explained in a recent phone interview. One of her artistic initiatives was a community project, “I’m Big,” which provided large sheets of paper and painting materials to women so they could draw giant self-portraits. “That was part of my journey to changing from the mindset [of] ‘I am small and weak’ and ‘I am just a woman’ to this understanding that I am big and I can make a difference,” she stated when describing the venture.

According to Tsvetkova, feminism is a subject that is viewed with fear and suspicion throughout Russia, especially in the eastern part of the country where she grew up. This attitude is disseminated through sexist language in the media and among the political leadership. The people themselves are apprehensive about being associated with the “dirty word,” feminism, which could jeopardize their social standing. “Many women who I know, they are feminist inside of them, but they would never say it publicly,” Tsvetkova explained. Through projects such as “I’m Big,” Tsvetkova hoped to dispel misconceptions and inspire courage among her compatriots to announce their views. “It was a big part of what I was doing, to show people that feminism is not scary. Activism is not scary. LGBT in general is not something to be scared of,” she said.

Yet Tsvetkova’s activism ultimately made her the target of state-led persecution. Her art work first reached the purview of law enforcement after the notorious homophobic public figure Timur Bulatov filed written complaints against her with the police in February 2019. Based on these complaints, police began investigating a children’s play Tsvetkova was staging in her hometown with her activist comedy theater group, Merak. The play, entitled Blues and Pinks, interrogated gender stereotypes in order to combat bullying and discrimination among young people; boys can cry, and girls can be strong, the play proposed. According to Tsvetkova, the authorities summoned her, her mother, and even the child actors in the production for questioning based on insinuations that the play promoted homosexual relations among minors. Tsvetkova was forced to close the theater company in response to police harassment.

The following month, Tsvetkova was interrogated by the police for a series of allegedly pornographic drawings she posted on social media, in an artistic campaign called “A Woman is Not a Doll.” The drawings, which promote body positivity, were accompanied by slogans such as “Real women have gray hair and it’s normal,” “Real women menstruate and it’s normal,” and “Real women have imperfect skin and it’s normal.” The police, however, could not prove that the images were pornographic.

In December 2019, following her house arrest, Tsvetkova was convicted under the so-called “gay propaganda” law for managing one feminist and one LGBT-themed social media group. She was fined 50,000 rubles (US $780) as punishment. The “gay propaganda” legislation, signed into law by President Vladimir Putin in 2013, is “aimed at protecting children from information promoting the denial of traditional family values.” International bodies have condemned the law as highly discriminatory and harmful, especially for LGBT youth.

Tsvetkova was freed from house arrest four months later, on March 16, 2020, and has been under town arrest ever since. She says these severe restrictions on her freedom of movement have created an oppressive environment, inhibiting her ability not only to travel but also to think clearly, to work, and to take care of herself and her mother.

The psychological pressure put on Tsvetkova extended beyond her imprisonment to encompass various intimidation tactics employed by the police. After Tsvetkova was arrested in November, a group of 10 unidentified individuals (whom Tsvetkova suspects were police officers) entered her apartment, took videos of her belongings, and posted them on social media, where they were met with a barrage of nasty comments. She submitted formal complaints about the illegal entry, only to be threatened, in September, with potential new charges that she had spoken negatively about the police. She has been subjected to random anonymous searches and the destruction of her personal property. Police officers sometimes leak information about her criminal case, then accuse her of illegally providing classified material to the press. She says that the police even went so far as to kidnap her pet cat, only to return it three weeks later.

“[The police] try to literally drive a person mad,” Tsvetkova stated. “They have no limits, and that’s what scares me a lot, not just because I’m scared for my life or for [the] life of my cats or my mom or this personal fear, but also in [a] very broad and deep way, to see how these people have no control, no limits. That is so scary to think about what they can possibly do.”

In the past few months, Tsvetkova has also received death threats from various groups, including the anti-LGBT group Pila, which means “saw” in English. She has submitted nearly a hundred reports to police officers complaining about the dangers to her safety but has received no response — an unfortunately common experience among LGBT activists in the country. “At a certain point you get tired of this,” she lamented. “What’s the point of writing it over and over when nothing will ever happen?”

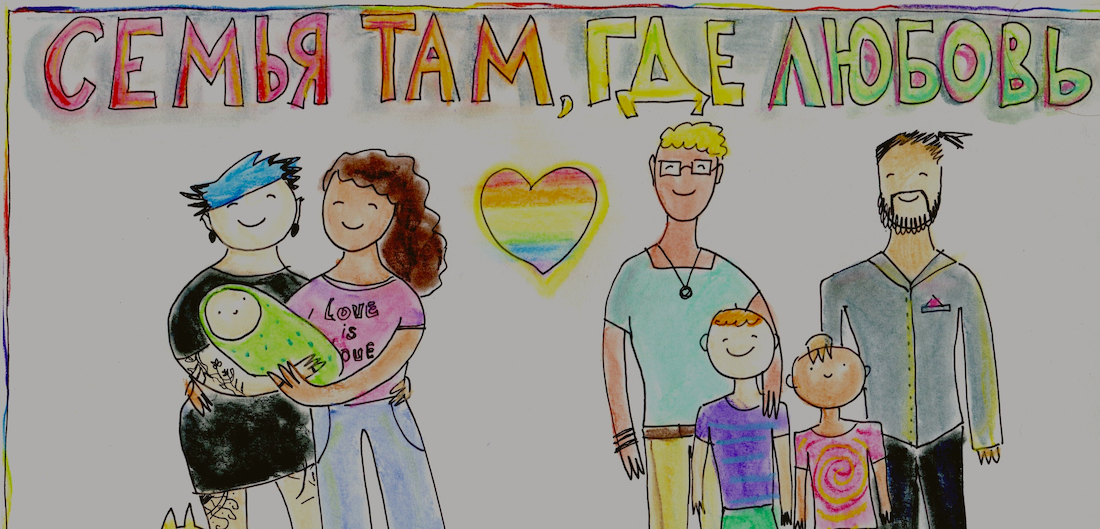

On July 10, 2020, Tsvetkova was once again convicted under the “gay propaganda” law and fined 75,000 rubles (US $1,000) for sharing a colorful drawing depicting two same-sex families with children, accompanied by the caption, “Family is where there is love. Support LGBT families!” (Her lawyer recently succeeded in getting the fine reduced to 50,000 rubles.) She still faces charges of “production and dissemination of pornographic materials” and awaits a court date in November. The accusations revolve around a social media page she runs called “Vagina Monologues” (inspired by the play by American author Eve Ensler), which shares artistic depictions of vaginas.

Residents of Tsvetkova’s hometown have varied reactions to her persecution. Some of her old friends and colleagues avoid her in the streets, unwilling to be associated with someone accused of disseminating pornography and advocating for LGBT rights. Others continue to support her in spite of the charges because they have known her since her youth. The most surprising demonstrations of solidarity have come from outside activist circles. Artists across Russia have rallied to Tsvetkova’s cause, hosting poetry marathons and media strikes in her honor. “People look beyond, it’s a case against feminists, and I don’t support feminism, and that’s it, but they go beyond that,” Tsvetkova explained. “It’s about art, and I am an artist, so I can understand that personally.”

In addition to exposing the perils facing vocal feminists, Tsvetkova’s case also highlights the recent crackdown on freedom of speech in Russia and the state’s preparedness to censor artistic expression in order to stifle dissent. In this context, the bravery of Tsvetkova’s public supporters appears even more noteworthy. “For them to go beyond that prejudice against activism or feminism and just say, I don’t really understand that part, but I know that there is injustice happening and I am against injustice, [so] I will speak up against it,” Tsvetkova continued. “That is what impresses me a lot.”

Human rights organizations have also spoken out about her case. The Memorial Human Rights Center, for example, has named Tsvetkova a political prisoner. “The crude interference of law enforcement agencies in creative matters and attempts to criminalize contemporary art, placing the function of art experts on police investigators, is absurdly anachronistic,” their statement reads. Indeed, it is a common practice in Russia for the authorities to open criminal cases against individuals who express dissenting opinions, with the express purpose of quelling activism. The criminalization of Tsvetkova’s art has less to do with whether or not her drawings are actually pornographic than with deploying the law to target an artist’s political views. “Pornography was an excuse for them,” Tsvetkova argued. “If they were fighting pornography, they would fight all the child pornography we have and all the violent pornography we have.”

From the outside, it would appear as though the police have succeeded in silencing Tsvetkova. She has stopped creating art due to the stifling pressure of the ongoing investigations. Her theater company has shut down permanently. The community center where she led civic initiatives on environmental sustainability and educational workshops on anti-militarism and the history of Stalinist repression has been closed. Most critically, authorities have seemingly undermined the goal of Tsvetkova’s activist work: to demystify normative perspectives and embolden her colleagues to raise their voices. “For me, activism was never something criminal or something bad or something to be scared or ashamed of,” she said. “Now people do believe bigger than before that all that is very scary. Feminism is very scary, it can get you to jail. Activism is very scary, it can get you to jail.”

Yet the continued campaign of persecution has failed to reverse Tsvetkova’s political beliefs and feminist stance. Her future is entirely uncertain: if she is found guilty of disseminating pornography, she faces up to six years in prison. She will live the rest of her life with a target on her back, under the strict surveillance of the government. Nonetheless, once her current nightmare ends, she plans to return to the activist world with renewed vigor.

Ultimately, Tsvetkova’s experiences have revealed to her the dynamics of repression and the prevailing potential for resistance. “I think I underestimated the power of art,” she said. “As it turns out, art is something so important for the government. If they are scared of art, that means that art has power, big, huge power, that I myself did not think was there. In a way, it is good to know that art — and women — are so scary for them.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Lillian Avedian is a writer for The Armenian Weekly, a historic community newspaper based in Watertown, Massachusetts. She is a graduate of the University of California, Berkeley with a Bachelor of Arts in Peace and Conflict Studies and a Bachelor of Arts in Slavic Languages and Literature. She applies her human rights expertise to uncover silenced narratives through her work as a journalist. Her reporting can also be found in Hetq and the Daily Californian.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Sovereignty Full of Holes: Russian Perspectives on Putin’s Russia

Daniel Treisman surveys three recent books that offer Russian perspectives on the Putin regime’s activities at home and abroad.

WhatsApps with Women #2: Joanna Walsh Talks to Artist and Curator Tamsyn Challenger about Pussy Riot

A conversation with Tamsyn Challenger about "Free The Pussy!," the recent exhibition on Pussy Riot.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!