A Carnal Contact with Reality: On Pasolini’s Novels

On a great director’s neglected novels.

By Daniel FelsenthalDecember 24, 2017

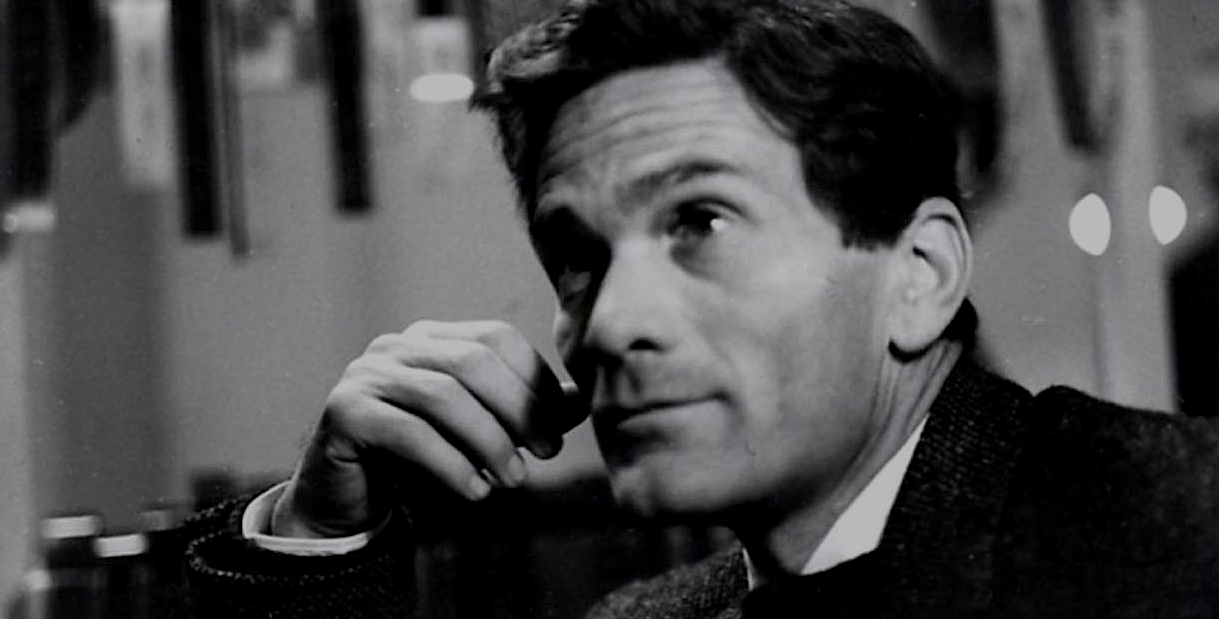

ARGUABLY MOST FAMOUS for the sordid details of his violent death, filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini wrote two novels during the 1950s — Ragazzi di vita (1955) and Una vita violenta (1959) — that are all but unknown in the English-speaking world. William Weaver translated both novels into English, yet Pasolini’s fiction is not as widely read in the United States as that of Italo Calvino and Alberto Moravia, his fellow Italians and friends. In 2016, Europa Editions reissued Ragazzi di vita (as The Street Kids) in a new translation by Ann Goldstein, providing an opportunity for American readers to reassess Pasolini’s literary reputation.

Weaver himself admitted, in a 2002 interview with the Paris Review, that A Violent Life (as he titled Una vita violenta) is the only translation of his career with which he is unhappy. The novel follows a boy, Tomasso, from his beginnings as a prepubescent “snot-nose” to his premature death by consumption at the age of 20, through a beleaguered Roman underworld dominated by a natural-feeling yet largely fantastical sexuality. Tomasso and his friends (named “Shitter” and “Stinkfeet” and less scatalogical things like “The Patient” and “Brooklyn”) are impoverished Romans living first in the Pietralata, a suburb of shantytown huts, and later in the homogenous, fortress-like high-rises that postwar Italy erected during its “economic miracle” — a phenomenon Pasolini would satirize in his neorealist masterpieces Accattone (1961) and Mamma Roma (1962). In the novel, Tomasso and his friends pursue romantic targets of either gender, commit repeated acts of violence and petty crime, and flirt with political allegiances. The story unfolds episodically, like an anti-picaresque, in sprawling chapters that spiral outward to encompass much of Rome. In one poignant scene, Tomasso returns from prison to a bedroom in his family’s new, government-subsidized home. In the end, the only thing the boys seem to acquire is mass-cultural savvy. Their fates are both tied to and doomed by a booming Italy.

There is as yet no indication that Goldstein, who also worked on Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, will retranslate Una vita violenta, perhaps because her translation of Ragazzi di vita sparked little conversation in the English-speaking world. There was a piece about The Street Kids in the Guardian and another in TLS, but US reviewers largely ignored the book. Perhaps reflecting something about our national character, most American commentators who have written about Pasolini have explored conspiracy theories surrounding his 1975 murder. Even Pasolini’s contemporaries have taken the rather reductive stance that he was a prophet and a martyr: Moravia wrote an entire book about the intrigue of Pasolini’s death, in which he notes that settings from Ragazzi di vita and Una vita violenta were reflected in its gritty milieu. “The victim of his own characters,” Michelangelo Antonioni called his fellow filmmaker, who was brutally beaten with a wooden stick and run over by his own car immediately before the release of his best film, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975). An Italian jury charged a male prostitute with the homicide, but the court of artistic opinion has, nearly unanimously, ruled the killing to be a political assassination. In 2014, Abel Ferrara directed a movie about Pasolini’s final days (starring Willem Dafoe) and went so far as to claim — he later recanted this statement — that he knows the parties responsible for the murder. More than 40 years later, interest in Pasolini’s death still overpowers attention to his work, especially his literary accomplishments.

¤

A similar sensationalism has surrounded discussions of Pasolini’s sexuality. Pasolini was gay and attracted to boys younger than the age of consent in the United States. Every biographical account tells the same tale: at the age of 27, while teaching in Casarsa, he lost his job because of an encounter with three adolescents at a county fair. Forced to flee to Rome, he also lost his membership in the Italian Communist Party. Still, Pasolini — a lifelong Marxist — continued to write for communist publications and even named a collection of poems after the Party’s co-founder, the philosopher Antonio Gramsci. Legal trouble hounded Pasolini his entire adult life, and the fame his novels brought him in Italy had more to do with their judicial controversy than with their literary quality. In 1955, the Catholic Church deemed Ragazzi di vita obscene, and Pasolini went to court when the government banned the book. The author won, but his Italian publisher, Garzanti, censored Una vita violenta in advance of publication, most heavily during a scene in which Tomasso cruises men in a movie theater.

Pasolini dedicated his second novel to “Carlo Bo and Giuseppe Ungaretti, my witnesses in the trial of Ragazzi di vita.” The phrasing is both a heartfelt acknowledgment of two people who testified in his favor and a clever pun: the trials of the ragazzi (in English: boys) were the subject of all Pasolini’s early narrative fiction, as well as his first two films. His evocation of their hardscrabble lives and the ambiguities of their adolescent sexuality have a pungent realism, especially for the 1950s. As in some of the roughly contemporaneous work of William Burroughs, there is a perverse libidinous charge to the boys’ callousness and rambunctiousness and desperation. The frankness and immediacy with which Pasolini portrays youth is unique, however. Take this interaction between Tomasso and one of his classmates (from the first two pages of Weaver’s translation):

“Whaddya want? Fuckoff,” Lello said, not even looking at him.

“You doing the cleaning up today, after school?”

“That’s right,” Lello answered curtly.

Tomasso sat down near a little pile of stones that served as a goalpost. After a little while Lello looked round at him.

“Getcha ass outta the way.... Whaddya want anyway?” he said, turning back at once and staring at the centre of the field, where the others were chasing the ball, with a steady stream of curses. Tomassino shut up: calmly keeping his legs crossed over the dried mud, he took a butt from his pocket and lit it.

Lello soon gave him another glance and saw he was smoking. With one eye still on the field, he was quiet for a while, then, in a lower, hoarse voice, he said, “Tomá, how about a smoke?”

Tomasso took another couple of drags quickly, then stood up to give the cigarette to Lello, who accepted it without losing track of the ball. He began to smoke, narrowing his eyes, still prepared to hurl himself into the game.

Tomasso stood there, his hands in the pockets of his shorts, which were held up by a length of string. They were so big they looked like a skirt.

There is an unsentimental directness in this passage, a vivid depiction of both the idle patter of the young and the extent of their poverty. With a barely perceptible irony, Pasolini also manages to convey Tomasso’s loss of innocence. Note the way the narrator refers to him by his diminutive, “Tomassino,” when he begins to smoke a cigarette. The extensive use of slang and dialect is an innovation Pasolini wrought on Italian literature since his earliest poems, which he composed in the Friulian dialect of northern Italy. And while the imagery recalls both Accattone and Mamma Roma, Pasolini would not replicate his novels’ casual mingling of the sexual with the quotidian until the very end of his film career.

What does Tomasso, as Lello asks, want? The reader finds out a few pages later, during a veiled scene in which the pair go into the bushes to masturbate. Tomasso also wants Lello’s job cleaning up the classroom after school, because Lello has sex with the young teacher who oversees him. Tomasso pays Lello 250 lire for the privilege of a day’s clean-up duty, only to discover the teacher is not interested in him.

The teacher raised his head with a serious, worried expression, then asked, so softly he was almost inaudible: “What’s wrong with Lello’s mother?”

“Don’t know, sir. She’s sick.” Tomassino said, still arranging his pants over his guts. The teacher let it go at that and looked down at his desk again. It was dark now, but what little light came through the windows, filling the room, seemed almost blinding in the frozen air.

Tomasso was still there, motionless on the bench, his face half-sly, half-bewildered, furious.

“Whaddya waiting for, shithead?” he was thinking. “What’s wrong with me? I’m as good as Lello. I’m better than anybody in this class. You think I don’t know my way around? I was the first one to catch on to you, you dope. I told Lello, even before you started in on him. But he’s stupid. I know a lot more about it than he does!”

While Tomasso was thinking in this way, becoming more and more angry, the teacher blotted the ledger, closed it, and stood up. “Let’s be going,” he said, “it’s late.”

However pleasurable the sinuous progression of these passages may be, they also draw one’s attention to an awkwardness in the translation. Pasolini’s use of slang and neologism is highly various, regionally specific, and unabashedly adolescent, circa 1959. Weaver, in turning Una vita violenta into A Violent Life, chooses to update certain words while neglecting others. “Snot-noses,” which the third-person narrator uses to refer to little kids, sounds antiquated and quaint in English, while the epithet “faggot,” which the narrator uses to refer to gay men, makes the perspective difficult to determine.

In his review of The Street Kids for the Guardian, Paul Bailey describes Goldstein’s use of “faggot” as an inaccurate translation of less harsh Italian slang. Bailey mentions that Weaver’s A Violent Life suffers from a similar difficulty with the nuances of street language. Still, the translator is not completely at fault: the loose way Pasolini plays with narrative perspective poses its own difficulties for the reader. Regarding Una vita violenta, Pasolini once wrote that he “withdraw[s] into [Tomasso] to the point of a mimesis which is almost a physical identification.” Yet the narrative does not cling tightly to the protagonist’s point of view; rather, a free indirect third-person narrator floats freely among the characters, dipping easily into their thoughts and understandings of the world. Occasionally, Pasolini suggests that the narrator may be a boy on the edge of Tomasso’s gang, who relates his buddies’ fates and foibles with equal parts grown-up stoicism, fleeting empathy, and confused, posturing naïveté. At other times, the sophistication of the narrative voice exceeds the capacities of Tomasso’s gang, with the narrator adopting a more free-ranging, less stylized view in order to render a swiftly changing city and society.

These shifts in perspective are, to use a cliché, “cinematic,” and there are numerous moments in A Violent Life when Pasolini’s filmic sense, while exhilarating, is too great for the novel’s own good. It is thus not surprising that Pasolini’s first two films attempted the same painstaking project of cataloging the lives of his ragazzi. On film, he could smoothly capture the rhythms of the everyday that he had to work at more spasmodically in his novels. Film’s “object-like concreteness,” he once said, fulfilled his yearning

to reach life more completely. To appropriate it, to live it through recreating it. Cinema permits me to maintain contact with reality — a physical, carnal contact, and even one […] of a sensual kind.

The greater sensuality of the medium allowed sex to be conveyed more implicitly, in the intimate feeling of the camera for the characters. It would be many years before Pasolini would broach this subject with the level of explicitness evident in his early novels.

¤

Pasolini’s blanket affection toward Roman youth faded as the 1960s took shape. The ragazzi became, in his view, subject to the same forces of global culture that informed the rest of the Western world. After the release of Mamma Roma, Pasolini made a short film entitled La Ricotta (1963), a subversive comic gem that served as something of a pivot away from his evocations of young ruffians. On the set of La Ricotta, he met a real-life ragazzo, Ninetto Davoli, with whom he had the longest and most significant romantic relationship of his life. Pasolini was 40 when they met; Ninetto was 15. When he himself was older, Ninetto spoke of how his older lover felt about him:

[I]t was like meeting himself as a younger person, as a boy. He saw in me the joy that he would have liked to have had, but hadn’t had. He saw the cheerful boy that he would have wanted to be but now could no longer be.

Pasolini cast Davoli in a small role in his next movie, The Gospel According to Saint Matthew (1964), with his own mother playing the Virgin Mary. This film now seems like a prophecy of the director’s ascetic, productive life, as well as his martyr-like end. Yet his movies were never fixated on death, and it is surely no coincidence that Vita appears in the titles of both of his 1950s novels. That said, his mature films were obsessed with erotic frustration and the paradoxes of sexual “liberation”: Teorema (1968), for example, includes a queasy scene in which an older man, snubbed by the boys he cruises in the bathroom of a railway station, tears off his clothes and staggers into a barren desert.

Pasolini’s reactionary response to the contemporary world only intensified as the ’60s stumbled on. The same year of Teorema’s release, when protesters occupied the modern art gallery and architecture department of La Sapienza University, Pasolini took the side of the government. “When you clashed with the policemen at Valle Giulia,” he wrote to an implied audience of educated urban youth in a late-career poem, “I sympathized for them. Because policemen are children of the poor.” He opposed abortion, the legalization of divorce, and birth control, and believed, or so he said, that homosexuality was a more effective means of battling overpopulation than the use of contraception. Early in his essay “Unhappy Youth,” completed months before he died, Pasolini wrote that

[A] moment came in my life when I had to admit that I belonged inescapably to the generation of the fathers. Inescapably because the sons are not only born; they have grown up, and they have reached the age of reason; their fate, therefore, begins ineluctably to be what it must be by turning them into adults.

These last years I have studied these sons for a long time. In the end my judgment, however unjust and pitiless it may seem, even to myself, is one of condemnation. I have tried to understand, to pretend not to understand, to rely on exceptions, to hope for some change, to consider the reality young people represent historically, that is to say beyond subjective judgments of good or evil. But it has been useless. My feeling is condemnatory.

It was as though he was saying to the children of Italy, and perhaps to the many boys he had slept with, that they were at fault for his inability to understand them. His contemporaries made much of the way his politics became inseparable from his sexual and romantic desire as he aged. “Pasolini […] [was] the ideologizer of eros,” Calvino wrote, “and the eroticizer of ideology.”

¤

The director’s most unabashedly erotic films were the so-called “Trilogy of Life” (1971–’74), three bawdy adaptations of medieval story cycles: The Decameron (1971), The Canterbury Tales (1972), and Arabian Nights (1974). It was on the set of The Canterbury Tales, perhaps the worst film Pasolini ever made, that Ninetto told his partner he was leaving him for a woman his own age. Pasolini later disavowed the trilogy in an essay written months before his death, in which he relates how he had become disgusted with all forms of sexuality. He was also disgusted with the trilogy’s incipient influence on Italian pornography, a feeling powerful enough to influence a change of course that led Pasolini to make his magnum opus, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom.

An adaptation of the Marquis de Sade’s notorious novel, updated to the era of Italian fascism, the film dismantles every vestige of the director’s own earlier romanticism. Salò focuses on a group of fascist aristocrats who collect teenagers in an isolated mansion, school them in the purported joys of unrestrained sex, and then torture and murder them in scenes of unsparing brutality. The relationship between the generations could not be more openly eroticized or more thoroughly irredeemable, a dire end to the violent life of Pasolini’s beloved ragazzi.

¤

LARB Contributor

Daniel Felsenthal is a music writer for Pitchfork and the assistant editor of NOON. His short stories, essays, and criticism have appeared in a variety of publications, including the Los Angeles Review of Books, the Village Voice, The Baffler, The Believer, Hyperallergic, Kenyon Review, and BOMB, among others. In 2019, his novella, Sex With Andre, came out in The Puritan, and he received a 2020–’21 Fellowship Grant from The Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture. He is currently at work on a novel and a collection of short stories. Read more of his stuff at Danielfelsenthal.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Neon-Neo Realism

Joseph Pomp on "Good Time" and the new era of Neon-Neo Realism.

From Sex Worker as Character to Sex Worker as Producer: A Review of Nicholas de Villier’s “Sexography: Sex Work in Documentary”

Nicholas de Villiers new book gives a fresh view on films about sex work by focusing on documentaries about sex workers, a genre that he calls...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!