Where Will You Take Me?

“'Time Pieces' comes across as a vexingly undecided little book.” Sven Birkerts on John Banville's Dublin memoir.

By Sven BirkertsApril 23, 2018

Time Pieces by John Banville. Knopf. 224 pages.

MIDWAY THROUGH his Time Pieces: A Dublin Memoir, novelist John Banville offers the unexpected observation that for all its historical texture and allure, he has not made much use of his adopted city in his fiction. “For me, as a writer in the making,” he confesses, “the fact was that Joyce had seized upon the city for his own literary purposes and in doing so had used it up, as surely as Kafka did with the letter K, and consequently the place was of no use to me as a backdrop for my fiction.”

The sentence landed crosswise for me. First, because it seemed a glib, and fundamentally false, admission for a writer — an artificer — of Banville’s stature to be making. I bridled at the word “backdrop,” with its implication that a fiction writer might just slide a piece of scenery into place, when everyone knows that setting is an integral part of any imagined world, as important in its way as character. Of course, there are writers for whom this is not true — K-obsessed Kafka, say — but Banville’s has always seemed a sensibility closely attuned to locale, as the title of this memoir would seem to attest.

Then there is the Joyce business, the idea that a place, a city, can be used up, drained by one writer of any further signifying power. If so, what a compliment to the master — but also what a backhanded insult to the city. I suspect that Banville was really talking about stylistic mastery, the idea that from his exile in Paris, Joyce accomplished such a stunning linguistic resurrection of his home city that his successors could only ever offer pale imitations. How could any writer hope to get the words to shine as shiningly?

But then again, has not Dickens similarly killed London, Balzac Paris, Proust the past, Woolf any place that is near water? To think so depreciates the writer’s creative power. And what about Time Pieces, the book in my hand — what kind of reversal is Banville now making, using the city as the eponymous center of his memoir?

There is no easy answer here. I find myself thinking how different writers have different expressive impulses. Joyce centered Ulysses in Dublin, but he used its concrete particulars to build a universalizing structure. He keyed his narrative episodes to the trajectory of Homer’s Odysseus, finding in the original epic an access to archetypes, thus allowing Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus each to be a kind of Everyman.

Banville strikes out in the opposite direction. Away from Everyman and, at least in part, toward getting inside the perceptions of the singular self — the “I.” I say this without prejudice. The macroscopically and collectively seen Dublin of Joyce becomes the idiosyncratically inhabited Dublin of Banville. The missions of the works are completely different. Banville, as memoirist, is not in a position of competing; he is not writing fiction. Besides — worth noting — the writer was born in the town of Wexford and only began to take possession of the city when he moved there as a young man. He can thus, at least in a work of nonfiction, tell it a bit slant.

If Joyce worked with a cartographer’s attention, using the most minute place details to create paths through the city — paths that are still regularly walked by Ulysses aficionados — Banville goes the other way. He puts himself almost entirely in the care of chance and the seemingly unscripted logic of personal association, allowing memories and digressive asides to proliferate as they will. His memoir has almost no sense of sequence. Instead, a curious constraint is imposed. The writer lets himself be taken to various Dublin “destinations,” these chosen by Cicero, an old friend. Cicero does not give Banville any advance notice: it is a most peculiar flânerie. Their meanderings, I should add, are accompanied by a generous array of photographs by Paul Joyce (no relation). His images — illustrative, atmospheric, or commemorative — open up out of the text like so many windows.

¤

Though billed as a memoir, Time Pieces is only occasionally personal in the memoiristic way. Banville works in many pages of chatty travelogue, complete with pocket histories of this or that building or event. There are also occasional philosophical interludes, even a few teasing personal asides. Such a mash-up of things may sound like a liability — to some extent it is — but it does also free the author from his penchant for full-on lyricism. He is a dazzling stylist in his fiction. But preening the pin-feathers might not be the best idea for an Irish writer looking to portray Dublin. His countrymen are known to be merciless around any putting on of airs. But by defying various genre conventions and mixing his modes of delivery, Banville manages to avoid the lash.

The book is deceptive at first. It does open with a more traditional lyric overture in which Banville recounts his charged first exposures to the great city. Banville’s own native Wexford is several hours by train south of Dublin, and it was a family ritual that he get taken to Dublin to visit with his Aunt Nan every year on his birthday. Scale is everything, and childhood is, as we know, the great magnifier. Every part of these day-visits is sense-saturated, and the boy’s live first impressions linger in our minds in the sections that follow.

Banville gets the savor of first arrival:

My mother and my sister and I — I don’t think my father accompanied us on those birthday outings — would arrive in Percy Place at mid-morning, bedraggled after the journey, drenched with rain and smelling like sheep. Aunt Nan would have prepared a birthday breakfast treat — the word “brunch” had not yet been foisted upon the language — of sausages, rashers, fried egg and fried bread, washed down with cups of teak-coloured tea, strong enough, as my mother would say, to trot a mouse on.

Gratifying the appetite is a key opening motif, but it gives way to a more ranging observation. A few pages later he writes:

During those long birthdays I must have eaten something besides breakfast at my Aunt Nan’s flat and a late-afternoon goblet of ice cream in rain-washed O’Connell Street. Perhaps there was lunch — we would have called it dinner — at Wynn’s Hotel on Abbey Street, haunt of loud whiskey-drinking priests and shady-looking types in trilbies, as well as the odd hopeful but no-longer-young lady in seamed stockings and a florid blouse, perched at the bar with a gin and tonic before her, and a cigarette, incarnadined at its lip end, clipped at a pert angle between the ostentatiously ringless fingers of her left hand.

There is a striking effect when the observations of the watchful child are transformed by the craft of the mature stylist. The boy noticed the woman at the bar, but it was the writer who made her cigarette “incarnadined at its lip end.” Very Nabokovian, this. The one instance can stand for a good deal more, for this lyricizing dynamic is at the heart of much of Banville’s work, especially later novels like The Sea and The Infinities.

These opening pages might prepare the reader to expect a more standard-issue memoir, one that seeks to bring the past to life even as it philosophizes about the nature of memory and the passing of time. The genre is haunted in this way. Banville certainly strikes the note early, writing, in what is for me catnip melancholy:

When does the past become the past? How much time must elapse before what merely happened begins to give off the mysterious, numinous glow that is the mark of true pastness? After all, the resplendent vision we carry with us in memory was once merely the present, dull and workaday and wholly unremarkable, except in those moments when one has just fallen in love, say, or won the lottery, or has been delivered bad news by the doctor.

This is phrasemaking at its most evocative. That “mysterious, numinous glow that is the mark of true pastness” feels like the very secret of memoir, which often has less to do with recollecting events than with discovering the sensation of a vanished time restored.

The passage whetted my anticipation. I imagined that Banville would use his great gift to pursue just such a search. But no, that road does not turn out to be the one ultimately taken. For with Chapter Two, “Cicero, Vico and the Abbey,” the writer introduces a very different voice — more public and garrulous, eager to deliver the sorts of lore we find in documentaries and travel guides. At this point he adopts — or is adopted by — Cicero, his aptly named friend (a “cicerone,” after the Roman orator, is an informative guide), who seems to know all the secrets of the city: “He can tell you the pub to go to in the North Strand where on the wall of the lounge bar you will find a chart of all the lighthouses and lightships in Dublin Bay, along with their signalling sequences.” Cicero fetches his friend for each separate outing; Banville looks and listens and lets himself be instructed. He has elected to encounter this densely storied metropolis selectively.

Cicero’s idiosyncratic guiding impulses get Banville off the hook structurally. He is not responsible for the itinerary. He can move willy-nilly from one location to another with no apparent rationale and no pressure to be exhaustive. The transit from site to site has a jagged contemporary velocity. This is Dublin in snippets, Dublin on the wing. Our charming and learned guide is talking to us over the shoulder as we scramble to keep pace.

So it goes. At one moment we are invited along to see the “disassembled but carefully preserved frontage and side wall of the original Abbey Theatre,” which had been founded by William Butler Yeats and Lady Gregory back in the early 1900s, and soon after we are paying a visit to the stone head of Admiral Nelson in the Dublin City Library and Archive (it had survived the 1966 explosion of Nelson’s Pillar by members of the IRA). On these excursions, Banville readily drops into his docent manner, which is informative but also feels a bit cobbled together from other sources:

Killiney Bay, to the south of Dublin city, has been compared, for grandeur and beauty, with the Bay of Naples, and rightly so. The affinity is celebrated in local place-names. There is Sorrento Terrace — a row of handsome houses standing at the north end of the bay …

What a relief when he gives over being instructive and confides something personal, as he does here when they are visiting the library:

I am embarrassed to confess that I sinned once myself, in that library: I stole a book. It was the Collected Poems of Dylan Thomas […] I had coveted the volume for months, and at last I could resist no longer: I hid it at the back of one of the shelves in the poetry section, waited six long weeks to see if anyone would disturb it, then stowed it under my coat and skulked out, my hands shaking in fright at the daring of the deed and my face on fire for the shame of it.

One exception to these various Cicero-originated interludes is the chapter Banville devotes to Dublin’s enormous Phoenix Park. The backdrop history here is a good bit more detailed, the biographical asides feel more thickly layered. Banville himself seems to recede as narrator; his recounting feels more dutiful. I registered this as I read, but only when I reached the end of the book did things click into place. For there, at the very end of the acknowledgments, Banville notes: “Fragments of this book first appeared, in different form, in City Parks: Public Places, Private Thoughts…”

I don’t have problems with an author repurposing relevant material — not if the material fits — but coming upon this citation I was irked. I had minded the obvious imbalance of material — and now felt slightly used as I understood the reason. Even more irritating was his “in different form” disclaimer. This meant that what had all along been orchestrated as a kind of happenstance “flânerie” around Banville’s Dublin was not at every moment happenstance — not when there were pages of good local color and anecdote to be repurposed. Some of the “spontaneous” charm of the enterprise began to wear off.

¤

Time Pieces comes across as a vexingly undecided little book. But though it doesn’t always live up to what had seemed its larger promise — that it will be a deeper mining of place and time — there are pleasures to be had. If Banville is not giving us the Proustian immersion, he does at least develop a few memoiristic threads that evoke his early days and partly compensate for the worked-up feel of other sections.

The early chapter called “Baggotonia,” for instance, takes us back to the early 1960s, to Banville’s first years in the city, when he lived in an area near Merrion Square called by that name. He makes clear that Dublin was his escape from Wexford and the provincial lives he saw his parents living. “They were,” he writes, “stranded in a timeless zone, preserved in the permafrost of what had already begun to be, for me, the past. Did my mother […] think of herself as old when she reached sixty? Did my father hear the distant, dark tolling of a funeral bell when he passed fifty-eight?” The passage is steeped in sadness — we understand why he had to leave.

In Dublin, Banville moved in with his Aunt Nan who lived in a large second-floor flat of a four-story house, which he describes in considerable architectural detail before moving on to recollect his various neighbors, including Anne Yeats, the poet’s daughter, who lived on the ground floor and who he describes as “a large shy shortsighted person person in her middle years.” He also confesses that he had a fervid crush on one of the neighbor girls — “a voluptuous and only slightly superannuated Lolita” — and … what else? Banville does not, it’s true, disclose too much in these pages, but from his scatter of particulars we get the impression of a self-conscious country boy looking to make his way.

And yet there are no accounts of early literary struggles or first triumphs. Banville is not at all forthcoming about his writerly formation, nor are his observations and anecdotes about other writers personally revealing. Rather, they are often worked in as asides and digressions. “Flann O’Brien […] I encountered only once, when on a twilit autumn eve I spotted him wobbling his way down a deserted Grafton Street with hat askew and coattails flapping in the October gale, a sad, drink-sodden figure.”

In the last chapter, “Time Regained,” he and Cicero go out to lunch with Seamus Heaney, and Cicero tries to get the poet to talk about the writing process, how a poem gets made. Heaney is unable to answer. Banville writes: “At the time Seamus was ill after a stroke, and the occasion, though as funny and entertaining as were all occasions that were celebrated in the vicinity of Seamus, was touched with a tender melancholy, a kind of shadowed sweetness.” This is as close as we get to the unguarded writer-self.

Time Pieces does not find a logical place to stop. There is no real culmination, no sense of circuit completed. The book ends because — well, maybe just because everything ends. In the final pages, the writer and his friend have gone to Cicero’s house, which looks out on a stretch of water where just then a renovated ferry is docking. It is Cicero’s friend Richie, owner of the restored boat, and he offers to take the two out for a ride. Writes Banville, “[I]t might be 8 December again, and I a child looking forward to a treat.” Passing under a stone bridge, Banville admires the concealed brickwork, remarking, “So much of the world is concealed from us.”

His last sentence, on a page opposite a photo of the author and Cicero sitting parked in Cicero’s 1957 vintage MG two-seater, facing open water, goes: “O time, O tempora, what places we have been to — and where will you take me yet?” The words feel a bit grandiloquent — especially given the haptic nature of the tour we’ve been on — but when do we not vibrate just a little to the call of first and last things?

¤

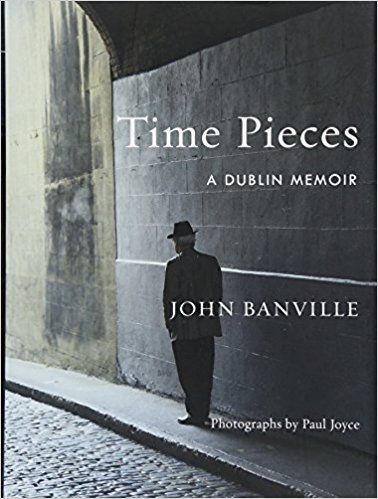

It would not be right to finish here without some comment on the 50 or so images gracing Banville’s text. Photographer Paul Joyce has a sophisticated compositional eye and a genuine range of subject matter. He can deliver the necessary public illustration — the facade, the monument — but he can also close in on the textured abstraction of a walkway or a crannied wall. He works in color and black and white, as the occasion warrants, and after some pages it starts to seem that Joyce is not just furnishing needed visuals, but is giving us his own version of Dublin. Like Banville’s, it is a place of history, not nearly as modern as the Dublin one might visit today. His is a city — interesting to think — that his namesake James would likely recognize as his own.

Joyce also offers several images of Banville himself, though these are never, whether by Banville’s choice or the photographer’s own, frontal shots. The writer is always turned away. On the cover we see him positioned alongside a slate-colored wall, standing still and looking contemplative. Then, later, when the text ends, we find a photo of Banville sitting with Cicero in the MG, facing out on open water. Last of all — a wonderful postscript — is a color photo of the author on a pathway in what a caption identifies as “Dry dock, Grand Canal Basin.” Banville is hatless, his silvery white hair catches the light, and his right foot is lifted, mid-stride. It is a light image, opposite of the solemn cover. He almost looks like he’s skipping. If I had wondered earlier about this facing away — whether he was looking toward the past, or toward the future — that final photo is unambiguous. It is full of the happy sense of looking forward.

¤

Sven Birkerts most recently authored Changing the Subject: Art and Attention in the Internet Age.

LARB Contributor

Sven Birkerts co-edits the journal AGNI at Boston University and directs the Bennington Writing Seminars. His most recent book is Changing the Subject: Art and Attention in the Internet Age (Graywolf).

LARB Staff Recommendations

The McPhee Method

Sven Birkerts considers John McPhee's "Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process."

Completing the Portrait: John Banville Tells Us What Isabel Archer Does Next

Thomas J. Millay reviews John Banville's "Mrs. Osmond," his continuation of "The Portrait of a Lady."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!