To Speak Upon the Ashes: On Peter Sacks’s “Resistance”

Isabel Ruehl reviews Peter Sacks’s first solo exhibition, “Resistance,” at the Rose Art Museum.

By Isabel RuehlDecember 21, 2022

WALK AROUND the gallery of Peter Sacks’s latest exhibition and first museum show, Resistance (curated by Gannit Ankori, director of the Rose Art Museum), and meet the eyes of 88 political, literary, and cultural figures, arranged into neat groups as though from a deck of cards. Hanging on one wall are mixed media portraits of Richard Turner of apartheid South Africa, Nasrin Sotoudeh of Iran, Plenty Coups (Alaxchiia Ahú) of the Crow Nation, and Langston Hughes of the Harlem Renaissance. Their grayscale faces peer out from layered compositions of color, fabric, paint, and text, creating abstracted patterns of prison bars, flowers, and arabesque. Streaming into the gallery is audio of several nameless voices reciting unknown passages. Straining your ears, just slightly, you make out some of the words:

The public must decide whether it wishes to continue on the present road, and it can do so only when in full possession of the facts. We still haven’t matured enough to think of ourselves as only a tiny part of the vast and incredible universe …

You don’t know whose words these are or who is reading them, but as you lock eyes with the figures, each seems to speak.

Throughout his multivalent career, Sacks has always been preoccupied with how artists can engage their practice in social reform. He grew up in Durban, South Africa, under the apartheid regime, in a white family that experienced their own forms of oppression as Lithuanian Jews, and who tried to resist colonial rule however they could. Sacks’s father taught medicine at an all-Black college; Sacks himself befriended Steve Biko and Richard Turner and likewise became a leader among student activists at the University of Natal, organizing demonstrations and giving speeches. At age 19, sidelined from anti-apartheid advocacy by the Black Consciousness Movement, which proposed that the cause was best served by an all-Black group, Sacks left South Africa for good in 1970. Studying abroad was a way to avoid enlisting in the colonial military, which mandated training for all men older than 18.

Before he became a painter, Sacks was a poet whose verse was highly abstracted, shaped by a keen awareness of the colonialist imposition of languages like English or Afrikaans. His poetry bucks this mandate by fragmenting and self-censoring; silence emerges as a vehicle of defiance and resilience. In the opening pages of Natal Command (1997), he writes, “If they capture me I have not learned to speak.” Silence is a refusal to call something into existence. For instance, he refuses to commit to paper the words “father” or “apartheid” in Natal Command, instead writing of his father’s death:

these words

re-opening:

Before. Not yet.

Not this.

This resistance strategy also imbues his painting practice, which he transitioned to from poetry, abruptly and completely, in 2000. In painting, written language is exchanged for the visual and the corporeal. More than the poet Sacks, the voice of the painter Sacks is even further removed; this allows more space to, in his own words, “freight” abstraction with materials, so it can “bear more of the weight of history.”

Unlike his poetry, Sacks’s trajectory and evolution as a painter over the past two decades has progressed from “explicitly abstract” to more and more figuration. Experimenting with movement and dimensionality, Sacks has increasingly gestured toward the human: a button here, a cuff there, a shred of lace to invoke the fingers that labored over its making. By the opening of his 2019 exhibition at Marlborough Gallery in New York, Repair, he had begun to singe and stitch whole shirt collars to canvases, running the shirt shoulders through a typewriter. Occasionally, he incorporated photographs.

Then came the chilly quarantine spring of 2020 and the news of George Floyd’s murder and the Black Lives Matter movement. Sacks again tried something new, directing his art practice toward abolitionist history and resistance in the United States. He constructed portrait after portrait of Frederick Douglass, thinking about how, in South Africa, the government prohibited citizens from carrying images of Douglass or any other social reformer who advocated against apartheid. Next, he created a series on Nelson Mandela. He couldn’t stop. He began to envision a larger network.

But Sacks felt the portraits were still missing something. He thought of Osip Mandelstam from the gulag, asserting himself against Stalin’s totalitarianism: “You left me my lips, and they shape words, even in silence.” Sacks no longer wanted to just figure resistance; he wanted to hear actual, vibrating words.

So he did: he explained through email to roughly 70 individuals — including Henry Louis Gates Jr., Joy Harjo, Colm Tóibín, Bryan Stevenson, and Michael Pollan — that he wanted to collaborate on an audio component for his new series of portraits. He invited his collaborators to record themselves reading aloud passages written or spoken by anyone from his curated list of resistance figures throughout history.

The call for submissions resulted in eight hours of voice recordings that Jorie Graham — a Pulitzer Prize–winning poet and Sacks’s wife — began winnowing and crafting into an audio collage of unexpected pairings: Tracy K. Smith reads “At the Fishhouses” by Elizabeth Bishop; Teju Cole reads Rosa Luxemburg and Mandelstam; Dwayne Reginald Betts, an American poet and prison reformer, reads the Ukrainian poet Serhiy Zhadan. These pairings substantiate Sacks’s hope for a kind of transcendence in the work, beyond any specific identity or geography or history, toward a “polyphonic” voice. (This is a word that the critic Sebastian Smee once used to describe Sacks’s visual work.)

Meanwhile, working on his portraits, Sacks continued to associate freely on the theme of resistance, representing cultural figures spanning the globe: Spain, Italy, Russia, Kenya, India, Korea, Japan, China, Iran, Peru, England, the States. Gandhi influenced Mandela, and Mandela influenced Sotoudeh. Federico García Lorca influenced Langston Hughes and Romare Bearden, another figure of the Harlem Renaissance, as well as fellow poets of the Spanish Civil War: Miguel Hernández, Antonio Machado, and Rafael Alberti.

To finish a portrait can take Sacks months — several morning-to-midnight days followed by weeks of recursive work, adding and subtracting materials and color to one portrait while laboring over another. With his finished works pinned to the walls of his studio, Sacks starts at the drafting table, feeling the eyes of history upon him. He takes a piece of aquarelle — thick and absorbent, it can carry the weight of cloth and collage — and rules off a rectangular frame large enough for the figure’s gaze to meet that of the viewers, face to face.

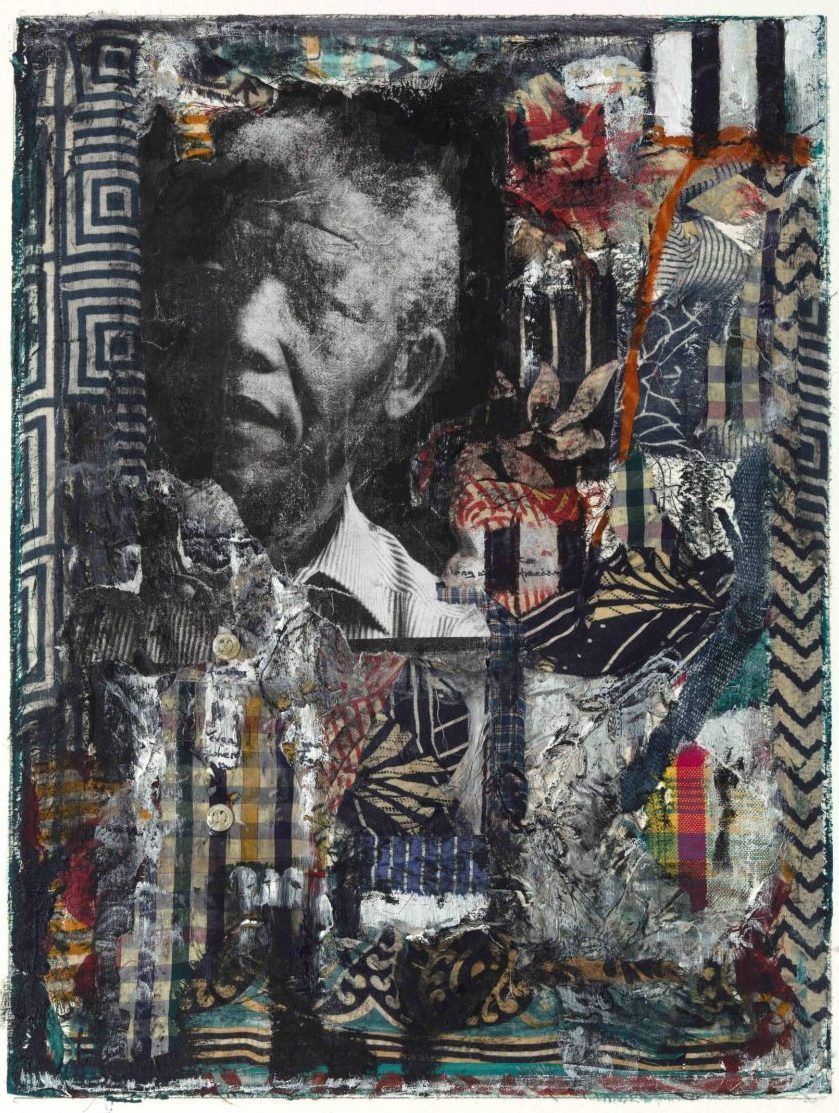

Then begins the layering, building up each canvas with materials that evoke the spirit of the resister. Sacks distributes textiles variously across his many diverse portraits, creating a formal continuity, and a shared history, between them. Curator Christopher Bedford, now the director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, has referred to this as Sacks’s “palimpsest.” Mandela’s frame, for instance, is filled with South African textiles, and a shred of Sacks’s father’s shirt.

Sacks has created 140 portraits and counting. Always the texturing and distressing within his canvases are allusive. Some, like Gandhi’s portrait, are balanced and centered, communicating stability and peace. More often the figure is off-center or bursting from the frame. Some, like Paul Celan’s, are slightly obscured by their surroundings, so that the viewer needs to work to see. Other canvases, like Sojourner Truth’s, are burned and painted over: a nod to Truth’s famous Indiana rally of 1863 in which Southern sympathizers threatened to burn down the hall where she was scheduled to speak.

When you enter and exit Resistance at the Rose Art Museum, there is another canvas by Sacks, from 2019, hanging to the left of the door. “Without Name” is layered, ripped, and burnt, with blue, red, and yellow fabrics streaking through heavy-painted lace and ridged cardboard. The work is inscribed with a quote by Walter Benjamin that addresses the 88 faces across the room: “It is more arduous to honor the memory of anonymous beings than that of the renowned. The construction of history is consecrated to the memory of the nameless.” “Then I will speak upon the ashes,” Truth once said, which is exactly what Sacks’s portraits achieve: they speak upon the ashes, invoking their viewers, all of us nameless, as a part of this history too.

¤

Isabel Ruehl is a writer based in New York City.

¤

Featured image: Peter Sacks, Nelson Mandela, 2020–2022. Mixed media on paper. Courtesy of artist and Sperone Westwater, New York. Photography: Gary Mirando.

LARB Contributor

Isabel Ruehl is an assistant editor at Harper’s Magazine.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Digging in the Dirt: On Jennifer West’s “Media Archaeology”

David Matorin reviews Jennifer West’s debut artist monograph, “Media Archaeology.”

Absolute Sovereignty: On Constance Debré’s “Love Me Tender”

Gracie Hadland reviews Constance Debré’s “Love Me Tender.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!