Absolute Sovereignty: On Constance Debré’s “Love Me Tender”

Gracie Hadland reviews Constance Debré’s “Love Me Tender.”

By Gracie HadlandDecember 8, 2022

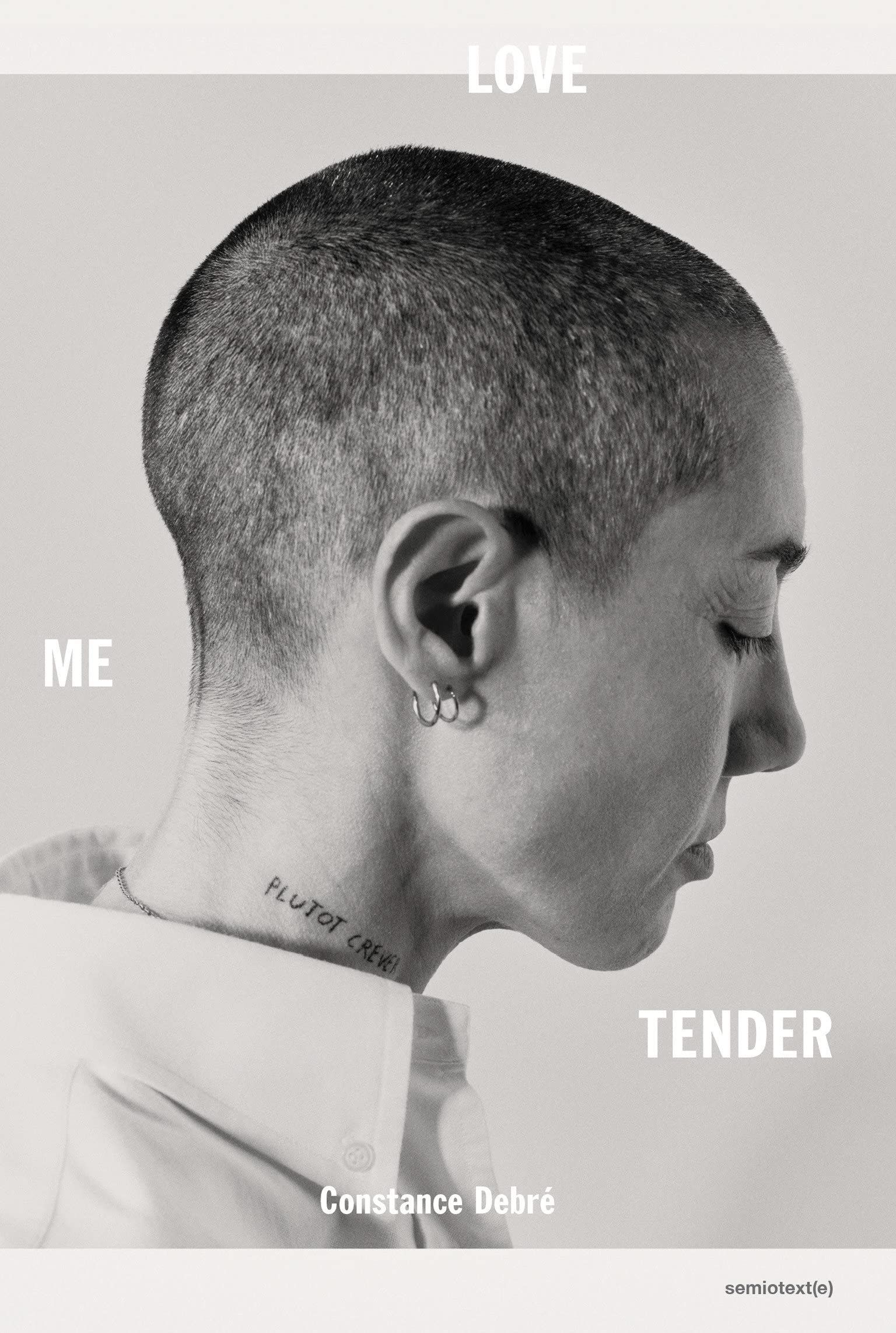

Love Me Tender by Constance Debré. Semiotext(e) / Native Agents. 168 pages.

“FOR ME, homosexuality isn’t about who I’m fucking,” Constance Debré writes early in Love Me Tender, her newly translated novel. “[I]t’s about who I become.” The book, Debré’s fourth, documents the aftermath of the narrator’s decision to leave her husband and career as a lawyer to pursue writing and begin dating women (the book can be read as a work of autofiction, the author and her narrator essentially interchangeable). As her declaration implies, a change in sexual partners is more than just that. The shift is totalizing; she becomes someone else. And yet, while there is a distinct before and after, the process of becoming that Debré documents is gradual and nuanced.

First published in France in 2020, and issued in translation this year by Semiotext(e), Love Me Tender tracks the narrator’s divorce from her husband and the subsequent custody battle for their son Paul. Three years into their separation, once she tells him she’s started seeing women, that ex-husband, Laurent, launches a campaign against her in order to keep her from seeing Paul. At home, he turns their son against his mother; in court, he accuses her of pedophilia, citing passages from books she owns by Hervé Guibert and Guillaume Dustan, both gay writers. Laurent appears over awkward meals, in coldly mocking emails (when the narrator writes him that she wants a divorce, he replies, “Stop you’re turning me on”), or in starker moments of conflict, as when he shouts at her to get out of his house. When she asks to discuss Paul or the ongoing court battle, Laurent says no — or simply doesn’t respond. She is trapped in a state of waiting: for permission from her husband, from the courts. Over the course of a couple years, she is granted permission to see Paul under state supervision, in sterile meeting rooms and with a strict time limit. By the time she’s allowed to take him away on weekend trips, there’s an unbridgeable distance between them. Eventually, she gives up. Like getting over a lover, she finishes grieving her son and moves on.

Contemporary coming-out stories are rarely so candid about the radical life changes that coming-out can entail. Mainstream “love is love” sentiments suggest that assimilation is the highest calling possible; the lucky gay person will slide back into middle-class comfort unaltered, except for the change in sexual partners and maybe a new haircut. But a smooth assimilation — or reassimilation — into a “normal” life is not what Debré desires, nor is it offered to her by the courts or her family. Love Me Tender is about becoming a lesbian, rather than coming out one. Debré’s becoming requires her to abandon things: material possessions, people, values. Some she chooses to surrender while others are taken from her. Some things she bequeaths to others; some are destroyed for good.

The book tracks these opposing trajectories: the old life that is falling apart and the new one that is coming into view. While the narrator’s family dissolves, she undergoes a kind of lesbian adolescence. This part of her life is expanding, changing the way she lives, whom she spends her time with. She begins swimming daily, dresses in men’s clothes, has affairs with multiple women at once, borrows money from friends, steals. She writes, “If I still had the same relationship to the world, it would have been much less hassle.” Debré is confronting the assumption that one cannot be both a lesbian and a mother/wife. She writes, “[T]hey tell me a mother can’t exist without her son, they tell me I must really be suffering, they tell me I don’t know how you do it, they tell me, they tell me, they tell me.” It’s as if she is forced, from the outside, to choose one identity. It’s as if her very existence is an oxymoron, a contradiction in terms. Elsewhere, she writes,

Lesbian lawyer, same life, same income, same appearance, same opinions, same ideals, same relationship to work, money, love, family, society, the material world, the body. […] But that wasn’t an option, that’s not how it works, I didn’t go through all this just for more of the same. I did it for a new life, for the adventure.

She recognizes the fallacy of this notion — “that’s not how it works.” Once one becomes gay, has sex with women, one’s relationship to the world is altered. It is a disruption; it throws all those bourgeois patriarchal family values into question.

By contrasting these two narratives — sometimes, almost provocatively, following a chapter about sex with a letter addressed to her son — Debré reveals the complex reality of living with these intimate relationships. Debré’s narrator is a novel protagonist. I was hard-pressed to think of a story in which the dramatic desperation of a mother’s loss of her family is coupled with the restlessness of a lesbian bad boy. The familiar narrative of tragedy — Debré as a Pietà figure, a grieving mother — is disrupted or complicated by the sex appeal of a delinquent on the run. There’s a kind of excitement inherent to her new life that doesn’t square with stories of similar subject matter that are overwrought with sentimental tragedy.

The act of purging, ridding oneself of excess, drives this transition. Debré writes, “My goal is to have as little as possible. Things, places, people, lovers, my son, my friends. I thought that was partly what being gay was about.” The new routine is precise and regimented, requiring only the basics, only necessities. She swims, she smokes, and she fucks; she eats standing up or not at all. It’s as if she’s training, preparing for battle, developing a strength that protects her from the world: “I’m getting stronger, more focused.” She takes her belongings and leaves them out on the street: “I don’t have any furniture apart from a double mattress I got from a discount store on rue Saint Maur and a plank of wood with trestles […] I don’t like stuff, I don’t have any pans, cutlery, or plates apart from a few disposable ones.” She describes adopting a monkish approach to living: “At first, I didn’t think I could get rid of the books, Homer, Baudelaire, Musil, Duras, you don’t dare throw them away. Then you realize you can, of course you can, nothing happens, they’re just things. I threw everything out.” There is a melancholy to her realization that books are just things, that you can throw them away. Despite being without the things society has deemed most important — money, family, stability — one is still alive. One can be without such things and still be okay, maybe even content. Rather than writing as a victim forced to give things up, Debré seems to write more from a position of the liberated. There’s a relief that comes with this purge, realizing she can do without things. Debré seems to be understanding the painful or perhaps liberating truth that one, ultimately, inevitably, is alone in the world.

I thought of Chantal Akerman’s Je Tu Il Elle (1974), her most explicitly lesbian film, which begins with a similar sense of spareness and isolation. The opening voiceover says: “And so I left. A tiny white room on the ground floor, as narrow as a corridor, where I lie motionless, and alert, on my mattress.” For the first 30 minutes of the film, the main character, played by Akerman, sits in self-imposed isolation, progressively decluttering. She moves all the furniture into the hallway, moves the mattress to the floor, blocks the light from the window, takes her clothes off, and eats sugar from a paper bag.

The austerity of this lifestyle — and the hunger that underlies it — is reflected in Debré’s prose. Like the small apartment filled with few possessions, her writing style is unfurnished and spare, sometimes even cold. The reader feels her dropping flourishes, writing with urgency, employing only the essentials. The poet and novelist Eileen Myles has compared writing to “running to catch a train, dropping luggage along the way. You just have to get on that train.” This means ridding oneself of excess, of unnecessary baggage, to get on something that’s already moving, as a means of survival. It’s a gesture of desperation, driven by a desire so strong that one is willing to give up things that one might even value or care for. It’s writing that requires one to take a risk. Short, plain sentences like the following:

Sometimes I think I could take off, leave Paris. Because nothing’s stopping me, no family, no job. Travel lighter. Really go away. Another city. Another climate. The sea. Or the road to nowhere. Hit the road, Jack. If only I had a car. But maybe it’s best I don’t, maybe I’d end up sleeping in it, never speaking to anyone, never needing anything again.

Debré’s voice recalls that of someone like Henry Miller, cool but virile. Yet, unlike Miller’s, which at this point scans as cliché (and perhaps misogynistic), Debré’s machismo subverts. The layer of performance here is obvious, the adjustments required by it evidenced in the narrator’s style transformation. If femininity is defined by a kind of excess and ornamentation, masculinity is just the necessities, no makeup, no boobs, no hair. As she indulges masculine tropes — promiscuity, criminality, detachment — her aesthetic becomes that of an outlaw, a man on the run. She even refers to her lovers as “the girls” giving them a number rather than a name. She writes, “Time to get rid. Time to get out. What else can I do but keep going, speed up, carry on living like a young man, a single bachelor. A solitary man, as Johnny Cash says. From now on I’m a lonesome cowboy.” The leap is what is profound, the discrepancy between the previous life and the new one.

Debré is from a prestigious French family. Before this rupturing event, she had a lucrative career as a lawyer; she’s certainly not living on the street. One might criticize Debré’s character for the assumption of working-class aesthetics; she writes about stealing food “for the beauty of the gesture.” I would argue, however, that the book is an account of the kind of class demotion one undergoes when one chooses not to participate, not to accept the social conditions required to remain in a bourgeois setting. Not only does Debré become a lesbian — she becomes butch: tattoos, a shaved head, a leather jacket. In her choice to live as the person she is, she is stripped of comforts she’d come to take for granted. This is the cost of her freedom. This kind of classlessness has been typical in the lives of gay people rejected by their families, who may have been cut off and taken work where they can get it — factories, civil service jobs. While it might be a phenomenon more common in the past, Debré shows that the bias against gay people still has material effects. This is why butch dykes wear their keys on carabiners, sport wife beaters, and have tattoos like sailors. While this aesthetic practice may have lost some of its potency since being co-opted by the mainstream, it retains significant cultural meaning, acting as a code among queer people. Besides being comfortable and possibly protective for its wearer, it signals a certain type of sexuality: more dominant, inflected with the power of masculinity.

At a reading I attended in Los Angeles, Debré told the audience, “In the first week that I had sex with a girl, I had the feeling I could write.” Perhaps the experience of becoming is best suited to the form of literature. There is something unavoidably erotic in the act of writing, communing with the deepest part of oneself in order to access a truth about oneself and one’s relationship to the world. It seems that part of this realization, this radical change, is what moves her to write. In Akerman’s movie, during the aforementioned first act, the character is focused; she writes pages and pages of a letter. She forgets the days, she doesn’t cry — she writes. Similarly, Debré, from the pain of circumstances in which she is denied autonomy, uses the practice to claim absolute sovereignty.

¤

LARB Contributor

Gracie Hadland is a writer living in Los Angeles. Follow her on Twitter @disgraciee.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Romanian Daedalus’ Surrealist Labyrinth: On Mircea Cărtărescu’s “Solenoid”

Ben Hooyman reviews Mircea Cărtărescu’s “Solenoid.”

The Body in Topography

Mariam Gomaa reflects on the intertwining characteristics of health, surgery, religion, and philosophy.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!