The (Yelling) Mothers of Us All

A new biography of a leading light — and loud voice — of second-wave feminism.

By Rachel ShteirApril 26, 2020

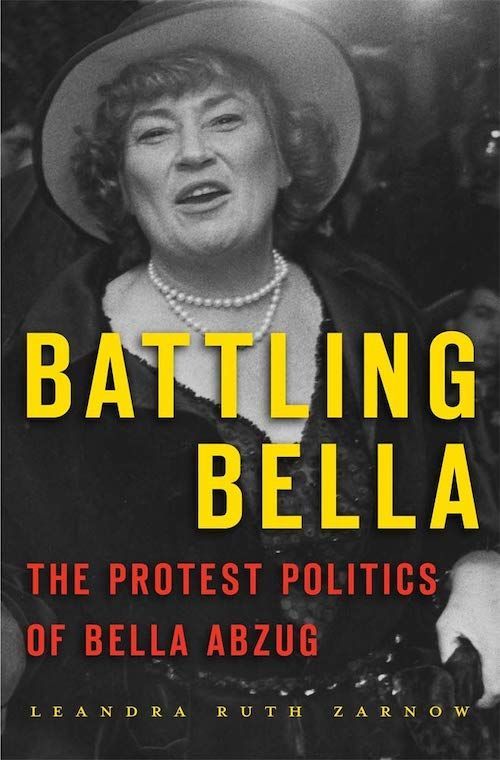

Battling Bella by Leandra Ruth Zarnow. Harvard University Press. 464 pages.

A FEW WEEKS AGO, after I told one of my favorite students that I was reviewing a book about Bella Abzug, she scribbled something in her notebook. “What are you writing?” I asked. “Bella Abzug,” she said, smiling shyly. And then a pause. “You teach us the best things to Google.”

The student, who considers herself a feminist, meant it (half) as a joke. But I tell this story less to complain about Gen Z than to note how the history of the second wave of feminism has faded. The student’s reaction alone is enough to make me campaign for Battling Bella, the first full-length biography of a leading figure of second-wave feminism published by a major academic press, to be required reading for every freshman. Every politician. Every woman and, of course, every man.

What I am saying is that, 50 years after the second wave, the movement’s history is mostly kept alive by the feminist historians who blurbed this book. We should be talking every day about the rights women have because of these towering heroines with clay feet. We should be complaining that women still don’t have equal pay or reproductive rights, despite these heroines’ efforts. We should memorize moments like the heartbreaking 1971 prediction of the National Women’s Political Caucus that, in 2020, half of the members of Congress would be women. In fact, roughly one-quarter of the current members are.

No one who knows the story of the heroines of the movement can read Leandra Zarnow’s new biography of Abzug, who died in 1998, without thinking of these disappointments and half-accomplishments. Zarnow, a historian and professor at the University of Houston, has written a tightly focused story about the political contributions of Abzug, who devoted her life to making American society less sexist and racist. It is a story that, in its selflessness and heroism, is unimaginable today. Abzug herself is also unimaginable now: she is simply too much — too strong, too loud, too opinionated, and too Jewish, of course. Based on the current political scene, I’m not sure female political figures have come a long way, baby.

Thus, we should all celebrate the fact that Zarnow rescues her subject from history’s attic, which may be as much as anyone can do.

But the book is not perfect. For one thing, Zarnow’s attempt to draw a line between the figure who was “born yelling” — as Abzug liked to say about herself — and #MeToo and intersectional politics is misleading. The second-wavers’ biggest bête noire was gender equity, not violence against women, which is one of the few things young women talk about now when they talk about feminism. And yet, Zarnow offers such a rich history in Battling Bella that I will forgive her this and other missteps, like the jejune way she often describes things (Andy Warhol is “tasked” with doing Abzug’s portrait, she writes early on).

Zarnow deserves credit just for making known Abzug’s long list of political victories, which came despite hectoring that makes Twitter look like a Hallmark card. A short list would include taking on HUAC’s anticommunists, Richard Nixon (she was one of the first to call for his impeachment), and Jimmy Carter, who dismissed her as co-chairperson of the National Advisory Committee for Women. She co-authored Title IX and supported both the Equal Rights Amendment and the Equality Act of 1974, which guaranteed the legal rights of gay people. Abzug also supported the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which banned gender discrimination in lending practices, and co-wrote the Privacy Act and the Freedom of Information Act Amendments. Older than many of the women in the second wave, she did not identify as a feminist at first, although she was living the life of one.

Abzug, an old-school populist, coined a number of enduring slogans: “Our Great Society is sick, and the major reason is that our priorities are insane”; “Our struggle today is not to have a female Einstein get appointed as an assistant professor. It is for a woman schlemiel to get as quickly promoted as a male schlemiel”; and “This Woman’s Place Is in the House — the House of Representatives.”

And yet, like her contemporary Betty Friedan, Abzug was a mixture of hauteur and generosity when dealing with her colleagues and rivals. “Everybody is people,” Abzug said in 1972 when asked why drag queens were attending her fundraiser. However (also like Friedan), her private life was far more conservative than the one she imagined for women in general. And she had a habit of judging people who failed to live up to her standards of the moment; as Zarnow reports, Abzug laid into Patricia Schroeder, the Congresswoman, for daring to work while raising children.

Zarnow begins Battling Bella by describing the emblematic ways the media and the public saw Abzug in her heyday — as Warhol portrait, as cameo in Woody Allen’s Manhattan, as pushy Jewish broad, as celebrity about town, as Category 5 hurricane. But this impressionistic beginning is misleading. The book is a conventional academic volume, arranged along chronological lines.

Abzug grew up in a milieu that will be familiar to students of the second wave. Born in 1920 in New York as Bella Savitsky, she learned from the soapbox orators of her neighborhood, as well as her family’s faith in Jewish law and ethics. Too devout to become a communist, she joined a Socialist-Zionist youth group. She graduated from Hunter College and then went to Columbia Law School, where someone described her as “a menstruating lawyer.” Her ability to withstand such harsh sexism was surely helped by her marrying the right guy, Martin Abzug, a stockbroker. He typed up her notes.

One reason second-wave feminism has receded is that, almost from its inception, younger women accused it of racism. Zarnow complicates this common wisdom by adding to the reporting of how Abzug dedicated herself to mobilizing against racism and sexism as early as 1948. Just out of law school, she defended Willie McGee, a black Mississippian accused of raping a white woman — Wiletta Hawkins — in the Jim Crow South. From 1948 to 1951, Abzug worked on McGee’s defense and appeal, introducing into evidence the claim that he had a consensual affair with Hawkins because Abzug thought to not do so constituted racism. Nonetheless, the all-white, all-male jury convicted him. During the trial in Jackson, Abzug risked her life. In 1951, after a hotel refused to let her check in, she hid overnight, while eight months pregnant, in a bus station bathroom, where she miscarried. Despite her efforts and sacrifices, she failed to get McGee acquitted and was even blamed for his death, the accusation being that her (alleged) communism had foiled her efforts.

But even as Zarnow celebrates Abzug’s courage, she barely mentions Susan Brownmiller, who, in her gloss on the case in her sensational and well-known book about rape, Against Our Will (1975), argued that leftist men, forced to choose between the word of an African-American man and that of a white woman, persistently chose the man. The omission is strange since, though some writers ridiculed Brownmiller, her skepticism formed the scaffolding for #MeToo.

But the omission is evidence of Zarnow’s flattening out of the second wave’s complications and contentions, which makes her book less rich than it could have been. She uses the word “surprise” twice in a paragraph when describing how, in 1961, Abzug, a leader in Women Strike for Peace (among the most significant antiwar efforts), resisted forming a coalition with the black freedom movement because she feared that women would be disappeared. There is nothing surprising about this: Abzug simply intuited that women might be unable to compete for resources against other marginalized groups.

But Zarnow is defter when she focuses on what Abzug did rather than what she said. And she is right to argue that Abzug’s personal style — storming and shouting in a way that largely doesn’t happen today — helped her legislative aims. She correctly documents the sickening spectacle of reporters and politicians discrediting Abzug by ridiculing her appearance.

And yet, Abzug’s failures cannot be pinned solely on misogyny. Like other “mothers” of feminism, Abzug didn’t speak diplomacy. She could be high-handed or bullying, which both galvanized disciples and alienated potential supporters. Some of her defenders would say that she had to be the way she was in order to be heard. But she also ignored — or maligned — conservatives, which did not help her later, as the political climate moved to the right.

Abzug’s career as an elected official lasted six years. In 1970, she ran for Congress in New York. She beat two Jewish Democrats, Leonard Farbstein and then Barry Farber. Because of redistricting, her seat was eliminated. She then beat the wife of William Ryan after Ryan died.

Her slide from relevance began in 1976, when she ran for the Senate and lost the primary to Daniel Patrick Moynihan by less than one percent. Part of the issue was that The New York Times came out for Moynihan, apparently by accident. Part of it was identity politics: her left-leaning Jewish identity tripped her up. Moynihan, who led the fight against Resolution 3379 comparing Zionism to racism, which was created at the International Women’s Year Conference in Mexico, positioned himself as “more Jewish” than Abzug. She did not help herself by saying that she would not support Moynihan if he ran. That seemed mean-spirited.

Abzug next ran against Ed Koch in the Democratic primary for mayor of New York. Koch also positioned himself as the more Jewish candidate. And here, too, Abzug did not help herself. A longtime atheist, she once said, on the campaign trail, about Hasidic Jews who were asking her about her devotion to gay rights: “You want to talk about perverts? Look at all these men wearing fur hats and ear curls.” Zarnow does not quote this remark. Yet it and many others like it are key to understanding why Abzug’s stint in politics was so short. She was not just brash — she could be vicious.

Zarnow claims that Abzug lost to Koch because she was not “a chameleon,” by which she seems to mean that Abzug was unable to feign interest in compromising, in moving rightward. “Her feisty personality now read as unhinged feminine emotion,” Zarnow writes. This is half true. But a successful politician needs to know how to collaborate, and Abzug never really learned how to talk to anyone who was not progressive.

Battling Bella is weak on Abzug’s private life — psychological insight is not Zarnow’s forte nor this volume’s purview. But it was hard, while reading, not to yearn for something like The Education of a Woman, Carolyn Heilbrun’s 1995 biography of Gloria Steinem, a brilliant example of examining the personal and political dimensions of a second-wave icon. Lacking insight into Abzug’s private life, Zarnow leans heavily on a critique of how the media made her marriage the butt of its jokes. But this is one place where Zarnow seems more credulous than any biographer should be. Maybe the Abzugs had a good marriage and maybe they did not. But just quoting Martin’s famous riposte, on an episode of The Mike Douglas Show that also featured Phyllis and John Schlafly, that their marriage worked because of “great sex” is unsatisfying, at best.

By the end of the 1970s, the second wave was in decline. In 1979, as noted, Jimmy Carter fired Abzug from the National Advisory Committee for Women. According to Zarnow, this is because she overstepped, criticizing the president in public. According to an earlier biographer, Alan H. Levy, the reason was the specific way Abzug criticized Carter, in her typical blunt fashion.

Abzug spent the last 20 years of her life trying to get back in the game. Zarnow ends her book in the ’80s, but Abzug went on to inspire women all over the world for years until her death. Perhaps this book will make it harder to forget her.

¤

LARB Contributor

Rachel Shteir is the author of Striptease: The Untold History of the Girlie Show, Gypsy: the Art of the Tease, and The Steal: A Cultural History of Shoplifting. Rachel has also written for magazines, newspapers, and blogs including American Theatre, Bookforum, The Daily, The New York Times, Slate, The Guardian, Playboy, The Los Angeles Times Magazine, Chicago Magazine, The Huffington Post, The Chicago Tribune, (the late) New York Newsday, (the late) Lingua Franca, The Nation, Tablet, Theatre, The Village Voice, and The Washington Post. Rachel also writes “The Rahm Report,” a column about Rahm Emanuel for Tabletmag.com. She is Associate Professor at the Theatre School at DePaul University.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Auspicious Conflagrations: The Heat of Women’s Anger

Bean Gilsdorf joins the chorus of women speaking about their anger, so that they can do something about it.

Letter to the Editor: Jenny Brown Responds to “Anti-Labor Politics”

Jenny Brown responds to Meredith Goldsmith, Anna Kryczka, and Catherine Liu’s “Anti-Labor Politics,” and the writers respond to her criticism.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!