Auspicious Conflagrations: The Heat of Women’s Anger

Bean Gilsdorf joins the chorus of women speaking about their anger, so that they can do something about it.

By Bean GilsdorfNovember 2, 2019

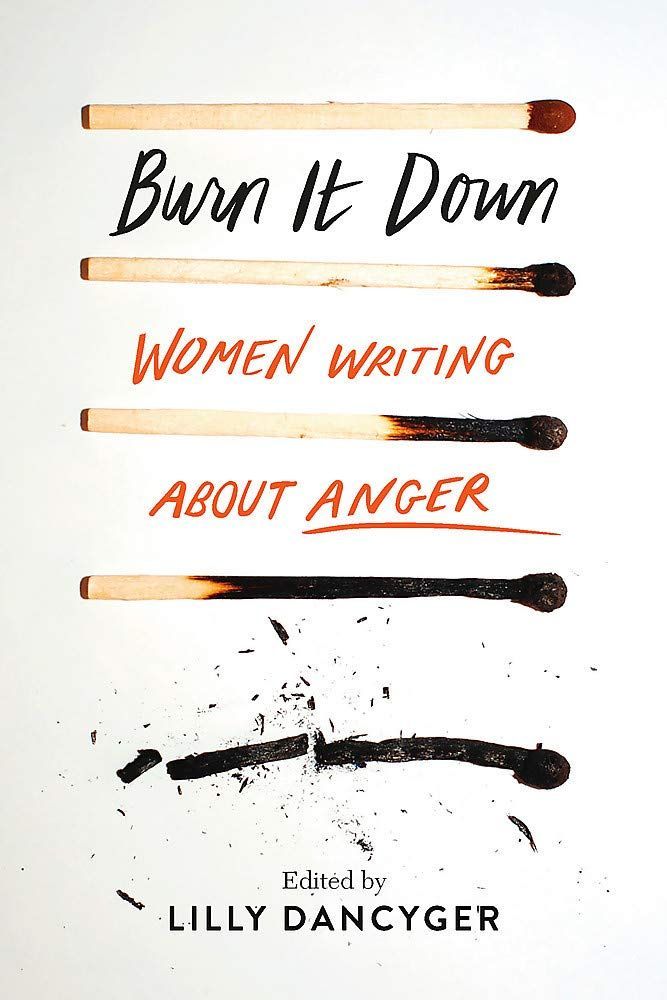

Burn It Down by Lilly Dancyger. Seal Press. 272 pages.

I NEVER THOUGHT that I would need books about women’s anger. For a handful of reasons both intensely personal and shockingly common, I grew up angry and have remained so my entire life. In fact, most of the women I know are angry, particularly in light of the last three years. The election of a white supremacist and admitted sexual predator to the highest office in the United States — which in turn renewed an onslaught of racist, misogynist abuse — has brought public, widespread expressions of fury to our news outlets, social media channels, and dinner conversations. The dismal news pours in every day: most of us are still making less money doing the same job as the guy in the cubicle next to us, almost 60 years after the Equal Pay Act was passed. As of this writing, there have been 279 mass shootings in 2019, many committed by men with histories of domestic abuse. Pop culture's alignment with #MeToo exposed some high-profile sexual offenders to the withering light of social censure, but there are still plenty of criminals wandering our schools, our churches, and our communities. The list goes on and on, and for me, the question is not the obvious why of my anger’s existence, but what I can do with it.

There are an estimated 3.8 billion women in the world, and I'd wager that nearly all have disquieting stories to tell. Therefore it should be no surprise that a number of recent books take women’s anger as their subject matter. Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger by Soraya Chemaly, Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger by Rebecca Traister, and Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower by Brittney Cooper are all single-author extended meditations that approach the topic from synergetic angles. The newest addition to this growing canon, the anthology Burn It Down: Women Writing about Anger, diverges from these in providing a venue for 22 essays by women speaking about their anger from a variety of perspectives: as trans women, cis women, queer women, journalists, poets, actresses, first-generation Americans, women who are dealing with mental illness and physical disability; women living in New York, Chicago, El Paso, Columbus, the Pacific Northwest, and western Massachusetts; Black, Xicana, white; mothers and the childless; middle-class, poor. This panoply of voices demonstrates that anger isn’t the rightful domain of a particular location, a race, or an economic status. The diversity of subjectivities serves two main functions: readers can find at least one essay in which they identify strongly with the author, and it creates a sense of sisterhood that could hypothetically transcend the typical boundaries that keep women from combining their considerable forces to enact change.

I’ll admit that I approached these essays optimistically, but also with a dose of skepticism. As a person already in touch with her anger, I wondered if this volume was meant to be a form of self-help for the apoplectic, or if the essays would suggest promising avenues for change. And what of the larger questions that this collection might address: Does the expression of anger, on its own, have merit, or is anger only valuable as a catalyst to action? What is the “it” we’re exhorted to burn down? There’s a sense of asked-and-granted permission in the editor’s introduction: Lilly Dancyger notes, “It’s okay, get angry,” and that is exactly what the authors do, in a confessional, intimate way. Though the urgent tone and relatively short length of each essay may tempt the reader to rush through, these stories are worthy of unhurried contemplation and definitely benefit from a little breathing room.

Overall, Burn It Down shares with the three books mentioned above the position that, though women have been actively discouraged from anger, they require it — to feel it, acknowledge it, express it, use it — in order to lead emotionally authentic, unabbreviated lives. Another notion the books share is that anger does not exist in isolation. Burn It Down’s opening essay by Leslie Jamison, “Lungs Full of Burning,” wrestles with the irreducibly messy territory of where sadness and anger bleed into one another. Whereas the majority of the other essays contain first-person reckonings with anger, Jamison surprises the reader by viewing this emotional phenomenon through the rivalry between Tonya Harding and Nancy Kerrigan and the way that the media of the time framed the story as “raging bitch and innocent victim, or bad-girl hero and whiny crybaby.” She reminds the reader that emotions are not dichotomies, and that women, especially women in the public eye, are socially orchestrated to be “cutout dolls” living within a flattened, bounded territory that prevents them from expressing the full dimensionality of their humanity. Monet Patrice Thomas’s “The One Emotion Black Women are Free to Explore” takes up this same argument against unidimensionality from a different angle, in which the racist stereotype of the “angry Black woman” clashed with instances of her anger existing alongside or being partially eclipsed by fear — situations in which expressing anger would have put her at greater risk for harm. Anyone who has found themselves in a similar circumstance, in which addressing an injustice directly and with honesty would make them even more vulnerable, will understand the detrimental effects that come from having to set aside your anger in the first place — a strategy that protects in the moment but over time compounds self-insult to the original injury. She concludes, “My anger has always been dismissed or overlooked, because it was superseded by the fear of what I’d lose by expressing it, whether it be my dignity, my safety, or my livelihood. Fear, I finally understand, is the one emotion that Black women are allowed to freely explore.”

Skirting fear by conforming to predetermined (and often suffocating) expectations is a common motif. Minda Honey, writing on her early life at home, notes, “Growing up, my mother taught us three girls how to read our father's moods like the weather[.] […] It never occurred to me to stand up to him, to raise my voice in return.” In terms of gender conditioning, some of the most illuminating essays are by trans women, who narrate how prior encounters with anger in their early emotional educations have shaped their understanding of culture and gender. In “On Transfeminine Anger,” Samantha Riedel talks about self-defense and her childhood discovery of anger as a masking mechanism, because boys are expected to get performatively angry as part of problem-solving: “This was the learned language of boys.” Later, she notes: “I’m still learning to recognize when I hold onto anger and use it for self-abuse[.] […] But the joy of expressing myself authentically is a greater reward than I ever could have dreamed, one that far too many women are still denied.”

Reading these essays arouses all of the emotional states that they contain: anguish, anxiety, disorientation, and indignation. One of the most galling is Sheryl Ring’s recounting of how a medical professional repeatedly misgendered her and then reached out and poked her breast “because she wanted to see if it was real.” At the end of “Crimes against the Soul,” Ring tells another story about a cis woman who commiserates with the author about getting hit on at work, only to follow with a transphobic comment. One of the nascent themes in this collection is how the casual cruelties of other women — from elementary school and the teen years through adulthood — are often the most riling, if only because women already face so much maltreatment from our pernicious, destructive patriarchy. It’s as if we thought there was a tacit pact to have one another’s backs, and so we are particularly stung on the occasions when we find it’s not true. Lisa Factora-Borchers’s essay “Homegrown Anger” recounts the girls at her lunch table smugly calling her mom’s Filipino food “dogshit,” and though it is one tiny part of an essay about xenophobia and Midwestern politics, it made my throat tight with commiseration. The subject of gender perfidy is taken up in more depth in Brittney Cooper’s book Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower, which deals specifically with the contradictions, complications, and gray areas of being a Black feminist within the overlapping spaces of cultural conditioning, contemporary academe, and American pop culture. In a chapter that’s mainly concerned with why she considers Beyoncé to be a feminist, the author takes a look at relationships, power, and “pretty privilege,” and says, “[F]or many of us, the first real injustices that mattered to us, that ripped our hearts out, weren’t the failings of our parents’ relationships, or the boys we crushed on who didn’t love us, but the Black girls who we wanted to see us and befriend us instead either ignored or bullied us.”

Not just anger, then, but also the betrayal that kindles it, are the themes that connect these essays (and these books) together like a network of threads — or fuses. Our disloyalty to ourselves when stifling our anger, the treasonous rejection of other women, the falseness of a medical system that doesn’t heal, the double-dealing of a government that doesn’t keep its citizens safe from harm: all these things are catalysts for the countdown to anger’s expression and its effects. Anger becomes a beacon, a flare sent up to tell you when you need to be paying attention to your body, your psychic boundaries, and your very being. Lisa Marie Basile’s “My Body Is a Sickness Called Anger” argues that anger is a force for self-advocacy within a medical system that frequently doesn’t acknowledge women’s illness and downplays women’s physical pain. Of the propulsive power that catalyzes her self-support in navigating both disbelief and bureaucracy, she writes, “[M]y anger has become my savior.” In “No More Room for Fear,” Megan Stielstra, recounting the scene of an active shooter on the Northwestern University campus where she teaches, notes,

Twenty-five years I’d imagined this moment and every time I was panicked, shaking; now, instead, I was white-hot and clenched, my muscles seething. Psychologists have long written about anger as a secondary emotion to fear, but I could give a shit about theory. This was gut-level; my body, my bones. I should not be under a desk.

All these mentioned above are excellent reasons to be furious, and letting off a little steam is healthy, unless, of course, it gets coded as natural for some people and abnormal for others. In the introduction to Rage Becomes Her, 392 pages of accessible scholarship on women’s anger, author Soraya Chemaly lists the impositions and restrictions that shape the expression of and reception to anger:

While we experience anger internally, it is mediated culturally and externally by other people's expectations and social prohibitions. […] Relationships, culture, social status, exposure to discrimination, poverty, and access to power all factor into how we think about, experience, and utilize anger. […] [I]n some cultures anger is a way to vent frustration, but in others it is more for exerting authority. In the United States, anger in white men is often portrayed as justifiable and patriotic, but in black men, as criminality; and in black women, as threat. In the Western world, which this book focuses on, anger in women has been widely associated with “madness.”

In other words, assuming a certain level of cultural competence, and depending on who else is in the room, you may or may not feel empowered to express your anger. The conceptual theories George Lakoff proposes in Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things sketch the linguistic roots of anger’s association with madness: in addition to the metaphorical connection between anger and heat (when you are angry you lose your cool, do a slow burn, and breathe fire), there is a connection between anger and mental illness (go crazy, nuts, bananas, berserk, raving, have a fit). But Lakoff doesn’t analyze these utterances by sex, so it bears saying that in the same way that history is told by the victors, our society allows men — specifically, white men — to tell our cultural stories, shaping the language and discourse around women's behavior. The more gender-neutral simmer and blow up are recast, for women, as the expressly feminine and irrational hysterical. This situation is exacerbated if you’re not white and Christian; in Burn It Down’s “The Color of Being Muslim,” Shaheen Pasha notes, “Too much anger and you’re seen as unstable, a threat to society with jihad coursing through your veins.” Thus the ongoing vacillation: women are angry, and we have very good reasons to be angry, yet we are told to not be angry, and we will be labeled as mentally unsound — even dangerous — if we show it. No wonder some women still need permission to acknowledge it. Even for those who embrace their anger, who among us has not waited until a more felicitous moment to express fury, or — under the weight of a lifetime of suppressed feelings — thought, I'm afraid if I start screaming, I might not be able to stop?

The “it” we are exhorted to burn, then, is nothing less than the circumstances that threaten our autonomy, dignity, and personhood, including our own internalized subjugation. Burn It Down is an impressive collection of essays; nevertheless, women who want to see large-scale social change must beware the ease of stopping at mere personal disclosure, no matter how assuaging the feeling of release. Lakoff categorizes a subset of anger metaphors as “heat of fluid in a container” (steaming, fuming, bottled up), and while it’s true that everyone needs to vent, there is a grave strategic pitfall to catharsis being the terminus of one’s efforts. This is not dismissive of the editor’s or authors’ work: personal narratives are crucial and need to be tended to; we are educating each other, leading to insight, connection, rapport, and, with effort, collectivity. Where we are divergent, they offer us a path back to one another. Megan Stielstra notes, “I don’t know if a story can save us — but it sure as hell can show us what’s worth fighting for.” In other words, in order to make real change, we can start by saying, I care about your screaming because I am also screaming; but that’s where the work begins, not where it ends.

Consciousness raising is an initiatory step toward long-term approaches necessary to overcome our instinctive American individualism, what we see as our personal problems and stories (despite their widespread relevance), the individualism which continually interrupts the construction of long-term systemic ameliorations. Over the last decade, we’ve watched the empowerment of self-care morph into capitalistic "me time" and the selling of wellness, an I-got-mine marker of social status in the form of an achievable semi-permanent performance of mental and physical health within a culture and environment that are profoundly unwell, unhealthy, sick, and deranged. Instead of making structural changes to public health care, self-care’s emphasis on separate, incremental actions twists the population back to propping up the status quo, with the deleterious effect of also blaming the individual for her own illnesses. Grappling with the territories of women and their anger, our individual stories are only truly valuable when they coalesce into collective activity, and we show up for each other in our homes, on the streets, in offices, boardrooms, and courtrooms. In the essay “Unbought and Unbossed,” Evette Dionne asserts, “[O]ur anger is our best gift, it allows us to blaze a new path,” and the most important word in this aphorism is us. There’s no such thing as an individual solution to a social problem. Self-help will end in self-destruction when — not if — it undermines collective support for social and legislative programs that lift all women up. Locating her adolescent anger and beginning to understand it, Melissa Febos writes, “It was like carrying a hammer for my whole life and finally realizing what it was good for.” Picture the power of a single hammer, and what it can fix; now imagine 3.8 billion hammers, and their unified, ringing blows.

¤

Bean Gilsdorf is an interdisciplinary artist and writer based in Portland, Oregon.

LARB Contributor

Bean Gilsdorf is an interdisciplinary artist based in Portland, Oregon. Working with appropriated images and texts, Gilsdorf creates work that delves into the relationship between historical narratives, the iconography of authority, and the ways in which representations influence our perception of cultural values.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Women in Knots: A Conversation with Sarah Rose Etter

Kate Durbin speaks to Sarah Rose Etter about her debut novel, “The Book of X.”

What’s Wrong with Popular Feminism?

Fran Bigman reviews Sarah Banet-Weiser’s new book on popular feminism, “Empowered.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!