The Word as Image: On “How to Read Islamic Calligraphy”

Emily Neumeier reviews "How to Read Islamic Calligraphy," a recent book from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and curator Maryam D. Ekhtiar.

By Emily NeumeierJanuary 22, 2020

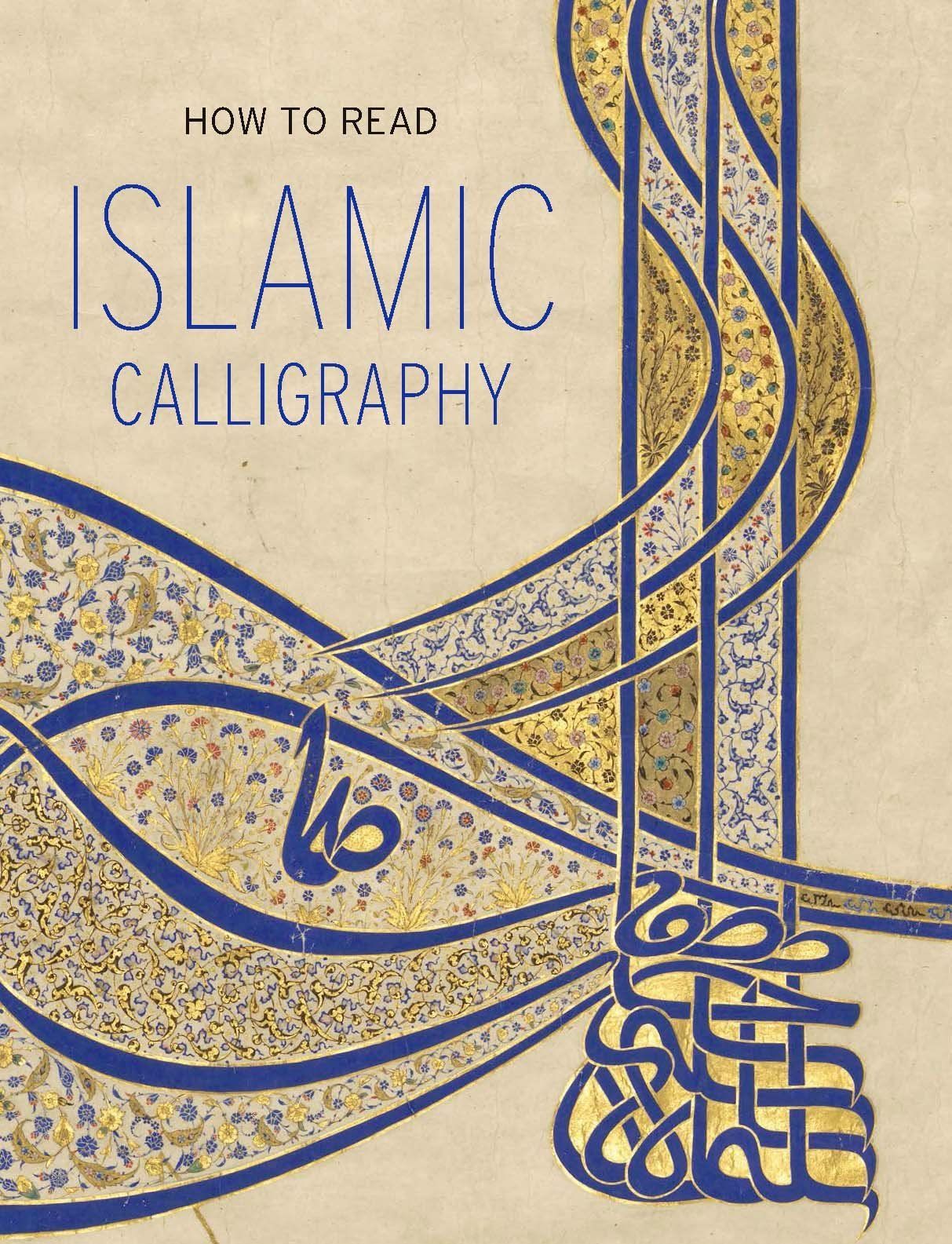

How to Read Islamic Calligraphy by Maryam D. Ekhtiar. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 156 pages.

THE ISLAMIC WORLD boasts an incredible diversity of art production, from the elegant tile mosaics of the Alhambra palace in Granada, Spain, to South Asian Mughal manuscript painting. Yet, within this diversity, it is impossible to deny the enduring and ubiquitous presence of calligraphy — the art of beautiful writing — throughout Islamic art and architecture. In the recent volume How to Read Islamic Calligraphy, Maryam D. Ekhtiar introduces her readers to this unique visual tradition. The book almost entirely draws upon the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which is one of the most extensive in North America.

Ekhtiar’s volume is part of a wider How to Read series of handbooks produced by different departments at the Met, designed to equip readers with the essential tools and background to appreciate an entire class of materials ranging from Greek vases to Oceanic art. While the series in general promises to prepare its audience to “read” all kinds of art objects, the resulting title for this specific installment is particularly apt, because it points to the most fundamental (and fascinating) characteristic of Islamic calligraphy: that it is an art form meant to be seen as well as read.

The book features three thematic essays explaining various aspects of Islamic calligraphy, each accompanied by a collection of individual case studies highlighting some of the more spectacular objects found in the museum’s collection. The author’s primary goal is to emphasize the unity of the art form, calligraphy being “the thread that binds” Islamic art across time, space, and media. Yet the catalog of objects also has a loose chronological organization to provide the reader at least with a general sense of artistic developments across more than a millennium.

The first essay, “The Arabic Script: Origins, Development, and Variations,” delves into the history of the text itself. As Ekhtiar explains, Islamic calligraphy is by definition in the Arabic alphabet, a writing system that emerged around the sixth century CE, just before the beginnings of Islam. Over the centuries, this system would come to be used for a number of languages, from Arabic to Persian to Ottoman Turkish to Urdu. This multiplicity is reflected in the variety of objects in the volume’s catalog. The fact that many readers have little to no experience reading Arabic text, and that even those familiar with the script may find some of the earliest and more abstract examples of Islamic calligraphy difficult to decipher, can pose something of a challenge. The author addresses this issue by providing a series of helpful charts that present the same phrase repeated in several different calligraphic styles, so that through visual comparison readers can appreciate how various kinds of scripts evolved and proliferated over time.

Perhaps the most striking development was the gradual shift, beginning in the 10th century, from an austere, angular script used primarily for early Qur’ans and architectural inscriptions — as exemplified by a page from the luxurious “Blue Qur’an” manuscript — to new styles of “rounded cursive scripts that were more versatile, efficient, and legible.” This stylistic transformation coincided with the introduction of paper to the Islamic world from China and a concurrent explosion in book production, amid the rise of increasingly literate communities.

The second essay in this How to Read volume, “Embellishing the Word of God: Arabic and the Art of the Qur’an,” underlines the deep connection between the Qur’an and the preeminence of calligraphy in Islamic art. Muslims believe that the Qur’an is the literal word of God as revealed to the prophet Muhammad in Arabic by the archangel Gabriel. Because the Qur’anic text is considered to be the earthly presence of the divine, it is worthy of elaborate adornment and decoration.

One of the most compelling examples of how art objects can enhance the meaning of the sacred word is a glass mosque lamp from 14th-century Egypt. Around the neck of the lamp a craftsman has outlined with blue enamel the text of the famous “Light Verse” of the Qur’an. This has been done in such a way that it is the calligraphy itself that is set ablaze when the lamp is lit, reading “Allah is the Light of the heavens and the earth,” a complex visual metaphor for the luminance of the celestial realm.

Ekhtiar also addresses the wider agency of sacred text within Islamic popular culture. For example, beyond conveying divine meaning, the Qur’an could also be used by believers as a source of protection in the form of talismans or amulets. In one case from India, the entire Qur’an has been transcribed onto a talismanic shirt, a garment that could be worn to safeguard from illness or even military defeat. The examples of the glass lamp and cotton shirt also raise the point of how ubiquitous the Qur’anic text is throughout the lived environment and visual culture of the Islamic lands, traveling far beyond the confines of the pages of a book.

In the third and final chapter, “Ornament and Abstraction: The Triumph of Form over Content,” the author considers examples of Islamic calligraphy that are so stylized that the text itself is difficult, if not impossible to read. Such works particularly draw our attention to the “blurred boundaries between text and image” that are inherent in most examples of calligraphy. The signifying power of the word in Islamic visual culture opened up the possibility for artists to explore increasingly creative and abstract calligraphic forms.

At times, intricacy to the point of illegibility was entirely the point, as is the case with the imperial seal of the Ottoman sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, a stunning object that graces the cover of Ekhtiar’s volume. Each Ottoman ruler had their own unique insignia that was deployed in official government documents, and the composition of the calligraphy was so complex that it was impossible to duplicate beyond the walls of the court workshops. But this was much more than prevention against identity theft. The seal of the sultan was designed to impress, with dramatically sweeping curves blossoming from a labyrinth of blue lines set against a gold ground. Through its abstraction of the calligraphic text, this work stands as a powerful icon of imperial authority.

This volume follows on the heels of a number of recent exhibitions on Islamic calligraphy in North America. The Freer and Sackler galleries (the Asian art museums of the Smithsonian) have lead the way: first with Nasta‘liq: The Genius of Persian Calligraphy (2014–2015), and then with the Art of the Qur’an show (2016–2017) — a timely exhibition that brought exquisite examples of Islamic manuscript arts to Washington, DC, just as national debates about the so-called Muslim travel ban seemed to be reaching a fever pitch. Looking even further back, some other landmark shows that paved the way for Ekhtiar’s book are Letters in Gold (1998), a visiting exhibition that was also at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Writing the Word of God (2007–2008) at Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

Overall, the book succeeds in providing museum visitors and armchair travelers with a toolkit to recognize and appreciate Islamic calligraphy found in a variety of contexts, especially if supplemented with the Met’s excellent online resource, the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The lack of footnotes makes it difficult for a motivated reader to follow up on a particular point or object in which they are interested, but the bibliography serves as a reading list for those who want to learn more.

Ekhtiar’s volume reflects a wider sea change in the field of art history that is concerned with revisiting the long-standing definitions of what “counts” as Islamic art. This more expanded view spotlights both contemporary works of art and objects originating from places often relegated to the periphery of the Islamic world, from Spain and North Africa to East Asia. One notable example is a blue-and-white ceramic brush holder from 16th-century China, which equally could have been produced for export or for the use of a prominent Muslim official in the Ming court — a testament to calligraphy’s high degree of cultural mobility.

My one issue with the volume is that it makes a chronological jump from 19th-century Ottoman calligraphy to contemporary artists who work in sculpture and painting but are also engaged with Islamic calligraphy as a visual vocabulary. This hundred-year gap raises the question of what happened to Islamic art during the intermediate period of emerging modern nation-states and global capitalism, a subject that is only beginning to be explored.

That said, I appreciate that the author has assembled a plethora of objects that remind us that Islam is not a monolithic, unchanging tradition, but one that encompasses a variety of viewpoints and lived experiences. Reading Islamic calligraphy is not just a matter of different artistic styles; it is also about trying to understand the multiplicity of its uses and meanings to different communities and at different times.

¤

LARB Contributor

Emily Neumeier is an art historian specializing in the art and architecture of the Islamic world. She is assistant professor at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture, Temple University.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Naguib Mahfouz, Storyteller

What “The Arabian Nights” has to teach us about the compassion — and violence — of stories.

A Journey with the God of the Qur’an

Ebrahim Moosa reviews Jack Miles's "God in the Qur’an."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!