The Politics of Care: On Angela Garbes’s “Essential Labor” and Peggy O’Donnell Heffington’s “Without Children”

Sarah Stoller reviews Angela Garbes’s “Essential Labor: Mothering as Social Change” and Peggy O’Donnell Heffington’s “Without Children: The Long History of Not Being a Mother.”

By Sarah StollerSeptember 8, 2023

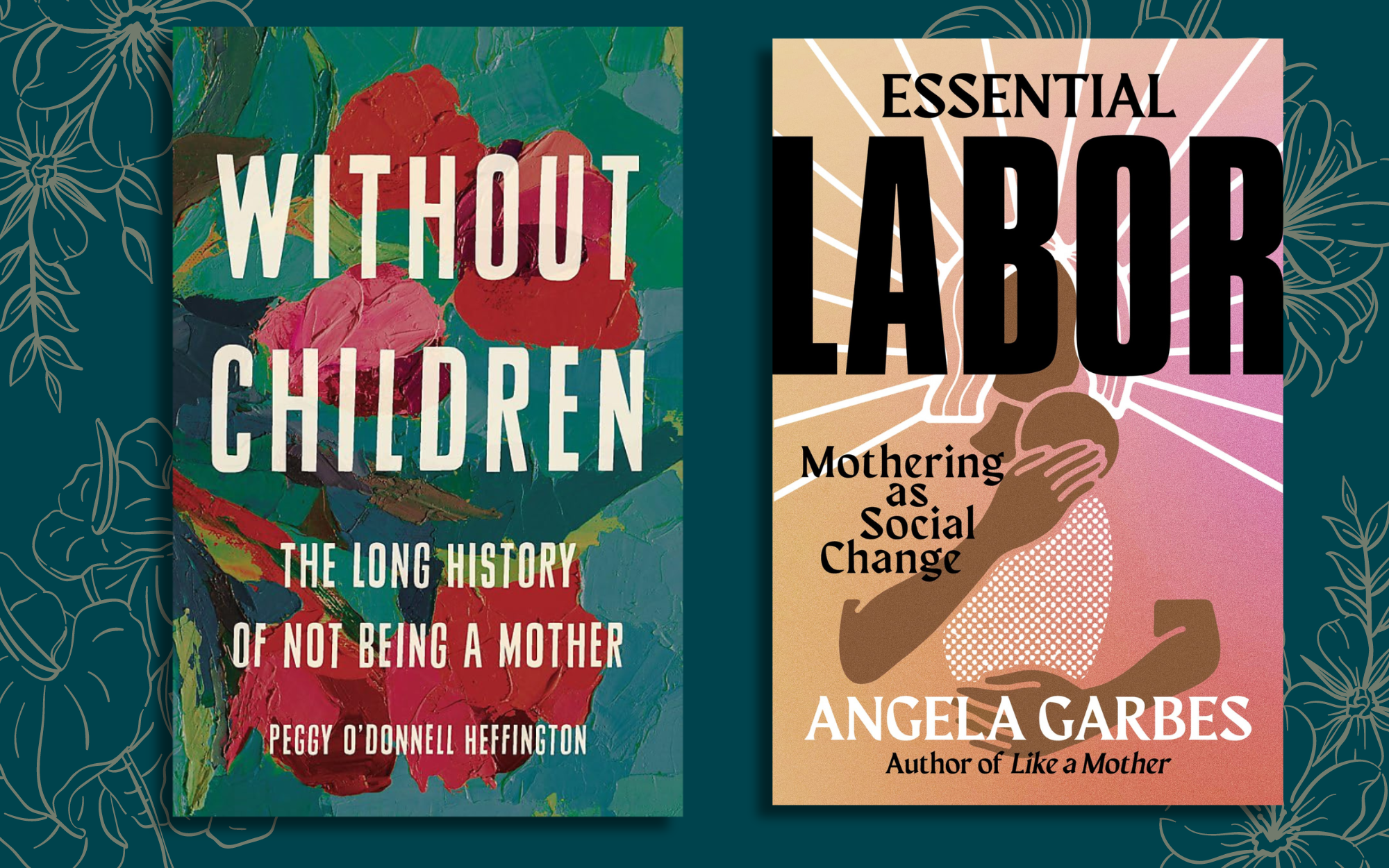

Essential Labor: Mothering as Social Change by Angela Garbes. Harper Wave. 256 pages.

Without Children: The Long History of Not Being a Mother by Peggy O’Donnell Heffington. Seal Press. 256 pages.

IN HER 2021 NOVEL Nightbitch, Rachel Yoder portrays the mother of a toddler on the brink of a total meltdown. When this mother gives up her career in the arts to stay home with her son, she is forced to reckon with her frustrated ambitions. She is isolated from her husband, removed from a broader community, constantly laboring, deeply in love with her child, and angry. In one stirring scene, the narrator, known exclusively as Nightbitch, meets up with two former colleagues—one single, the other a mother whose child is in day care. The evening begins on a happy note: she is in an expansive mood, ready to enjoy a meal prepared by someone else, and excited to talk to other adults. She’s high on the promise of feminist sisterhood. As it turns out, the somewhat snide professional conversation that follows leaves her feeling deeply alienated. In an explosive episode of rage, Nightbitch leaps from her seat, furiously overturns a table, and barks aggressively. The evening culminates in her literal transformation into a howling dog.

Nightbitch was published into a mid-pandemic chorus of raging mothers so pronounced that the surrealist dimensions of the work hardly registered as such. And yet, this isolation and fury has not been the primary conversation about motherhood to emerge from the COVID-19 era. On the contrary, the pandemic seems to have softened us to one another in recognition of our mutual vulnerability. As we’ve emerged from the acute tumult of the last few years, a rising chorus of voices has called for a renewed feminist politics of community that heals the divisions between parents and nonparents, among parents, and in society more broadly. This new current of maternalist feminism promises that we can render motherhood and child-rearing a shared community project and, in so doing, mother our way to social change. It’s an alluring premise, but as I look around and observe a materially rather-unchanged world, I find myself wondering, at times, if I’m missing something.

While I have continued to growl, two recent nonfiction books have made a radical case for a renewed feminist politics of care. From their different vantage points, both Angela Garbes’s Essential Labor: Mothering as Social Change (2022) and Peggy O’Donnell Heffington’s Without Children: The Long History of Not Being a Mother (2023) raise the question of why, in the midst of failed social policy, climate crisis, and neoliberal work culture, many of us continue to bring children into the world.

Garbes begins where the all-too-real Nightbitch left off: “In the current whirl of life, when professional work, domestic work, and childcare are all happening simultaneously under the same roof, it is easy to feel defeated by the duties of mothering. To view a child as a nuisance—and to feel guilty for the thought.” And yet her vision is profoundly hopeful. Garbes draws on decades of insights from Black, Indigenous, and queer feminists, imploring us to reimagine ourselves not as atomized households but as members of communities that share the work of care: “My time and attention are not so precious that I cannot give them to another child, another adult, another family,” Garbes insists. “They can be given freely because, it turns out, I have so much to give.” A life lived in community is one that promises to be far richer with meaning.

In considering the long and largely overlooked history of women without children, O’Donnell Heffington arrives in much the same place. From the outset, she exposes the entangled forces of circumstance and decision that have led some women not to have children. In doing so, she offers a way of moving beyond motherhood as an overdetermined function of personal choice, and of an identity politics so profound and pervasive that it positions mothers and childless women at opposite ends of a spectrum. For O’Donnell Heffington, a culture that sees mothers and non-mothers as opposites has constrained the identities and opportunities available to both. And like Garbes, she believes that the most radical thing we can do is turn toward each other and offer interdependence. According to O’Donnell Heffington, “We must think of the next generation as a project that demands work from all of us, not an individual one that parents must shoulder alone, if we have any hope of making it out of the crises that are coming for all of us: environmental, political, cultural.” Reading Garbes and O’Donnell Heffington, I feel almost saved. Both draw on a powerful strand within feminist thought that urges us to see mother as a verb, not a noun. A mother is a person who cares, and who does the often unglamorous work of care. Mothering is a responsibility of us all.

The notion of motherhood as an agent of social change has been part of Western feminism from the very beginning, and yet in recent years the matter of biological sex and identity has complicated the way we talk about care—at times as a practice fully detached from the body. Garbes, like Yoder, seems to grasp for a way to reconnect the impulses of care to something physical. Mother may be foremost a practice, not an identity, but it is one that is deeply embedded in our physicality. Garbes, in particular, venerates the messiness of bodies—feeding, grasping, undulating—in a manner that would have made the maternalist feminists of the late 19th century shudder.

If Garbes wrote very much in the shadow of the pandemic, O’Donnell Heffington is explicit about the influence of the COVID upheaval on her thinking: “I wince when I think about how close I came to writing a book that took a side in what Sheila Heti called the ‘civil war’ between mothers and non-mothers.” The vision both Garbes and O’Donnell Heffington offer is an undeniably beautiful one—a vivid ode to the power of community that could only have sprung from its recent absence. And while neither idolizes the work of care, the promise of togetherness is at times so potent that it can take on a spiritual quality.

Read alongside contemporary parenting and relationship advice, this recent work paints a picture of a society that needs some reminding about how to treat ourselves and others well. Garbes follows cultural critic Anne Helen Petersen in making explicit the ways we can build community. By exchanging or sharing childcare, sharing meals, delivering food to friends in need, and taking breaks from parenting and allowing friends to step in, we can support one another in ways that, if not totally outside of the market economy, aren’t bound by it either. While the likes of parenting guru Dr. Becky and relationship expert Esther Perel tell us to stop overinvesting in our own children at the expense of other axes of meaning, Garbes and O’Donnell Heffington give us glimpses of how we might do so. We have to embrace the vulnerability of expressing our needs, offer to help, and show up, perhaps especially for friends without children. We have to do it even when it’s hard and uncomfortable, as we should expect it will be.

Both Garbes and O’Donnell Heffington acknowledge the material context that shapes the lived realities of child-rearing and women’s identities and options in the United States. Yes, we desperately need universal childcare, high-quality education, healthy and affordable food, well-funded public spaces like parks and libraries, universal healthcare, environmental action, and a social safety net. And yet, in the absence of decisive political action on these fronts, community is what’s on offer. In the conclusion to her book, O’Donnell Heffington paints a moving portrait of a woman who, though she did not have children, was mother to many—as a Chicago public school teacher for more than 37 years. She was a woman who devoted her life to the work of care.

At the end of Yoder’s Nightbitch, the eponymous character experiences a profound transformation. Her rage, which hitherto had isolated her and removed her from a sense of community with others, becomes a force for artistic creation. She pursues a radical project that springs from dark, embodied maternal energies, and it proves redemptive—both for her and for the small community she is able to build around her. She is, I imagine, a character whom Garbes, especially, would admire.

As a feminist and a new mother of the COVID-19 era, it is hard for me not to be swept up in the very beautiful odes to community, care, and creativity that have emerged over the last couple of years. And yet, I wonder how hopeful I should be. I worry that calls for community reliance are just an expanded version of the impetus to self-reliance. I worry about the political: if and how we can find ways out of our immediate communities, shaped as they so often are by class, race, and other axes of identity, to ones that are more diverse. It is one thing to emerge from isolation—whether the isolation of new motherhood, or the isolation of being a woman without children in our culture—into personal redemption, be it artistic, professional, or otherwise. It is quite another to practice mothering outside of our families and most intimate communities. The material barriers to doing so are profound. The undulations of the market suggest none of the beauty of the undulations of caring bodies. Yet that, too, deserves our attention if we are to create a powerful new politics of care.

¤

LARB Contributor

Sarah Stoller is a writer and historian of women, work, and feminism. She completed her PhD on the history of working parenthood at UC Berkeley.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Activist Mothering

Suzanne Cope reviews Angela Garbes’s new book, “Essential Labor: Mothering as Social Change.”

Anti-Labor Politics

Anna Kryczka, Meredith Goldsmith, and Catherine Liu believe Jenny Brown’s “Birth Strike” still has some work to do.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!