The Inner Lives of Others: On Peter C. Baker’s “Planes”

Toral Jatin Gajarawala assesses Peter C. Baker’s experimental novel “Planes,” about terrorism and interlinked lives.

By Toral Jatin GajarawalaSeptember 20, 2022

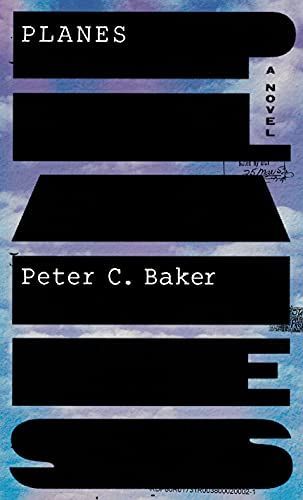

Planes by Peter C. Baker. Knopf. 256 pages.

IN PETER BAKER’s propulsive new novel Planes, four figures cross paths: Ayoub, sent to Temara prison in Morocco, for reasons unknown; Amira, formerly Maria, his wife who awaits him in Rome; Melanie, mother, realtor, and school board member, rekindling a passion for local activism; and Bradley, her occasional lover and the owner of Arcadian Airlines, a transport company in North Carolina that happens to run CIA renditions for extradited individuals. Nestled together in the space of the novel, these four lives hardly intersect in the real sense of time or space but on some other plane. In fact, the novel is the only plane on which they will ever meet.

Baker’s story about the inner lives of figures who are variously intercepted by American machinations abroad might be described, reluctantly, as a post–post-9/11 novel. After the initial efforts of Don DeLillo, Jonathan Safran Foer, and others, it attempts to reckon with American lives entangled with others — and with the other lives entangled with ours. Like John Wray’s recent Godsend, it offers a look at those lives that have been refigured by wars abroad and immigration home.

The novel begins with Maria, now Amira, and the grinding monotony of alarm, prayers, breakfast, work, walk, wait. This waiting for the disappeared Ayoub, two years now, casts a shadow over everyday life, over Rome, over her parents, over dinner, over the boxing cats at the window. She walks through Esquilino and pays her rent. She chats with the landlord’s son and an old high school friend. Abruptly, after 50 pages, and apropos of nothing, the channel changes. It is Melanie now, Melanie of Springwater, North Carolina, with a real estate license, wife to Art, mother to Michael. Art and Mel, gentle activists, now liberals, move from the kitchen to the school board to therapy to the bedroom. In between, they do internet searches: “Guantanamo,” “Springwater torture flights,” “Abu Ghraib.” Are we content to know so little about the lives disfigured in our name?

The key trope in this regard is redaction: prompted by the letters from nowhere that Ayoub writes to Amira, redaction is both a narrative and ethical principle. Heavily blacked out by the prison, like the CIA documents to which the novel often alludes, the letters say little. What can we know? As a result, the true metric scale of consequence lies in the miniature movements of self, rather than those of nations: in a series of moving notes, Ayoub coaxes, engages, and domesticates a cat, a skinny shadow of the one that circled the prison. In the portrait of man and cat emerges a tenderness that can only be the inverse of his tortures.

Redaction thus signals the sinister and secretive logic of American power but also the everyday rewriting, revision, of ourselves: “She clicks to retract the tip of the blue pen. Clicks to extend it again. On the new top sheet of the legal pad, she writes: This budget commits us to making sure all of Springwater’s children start the day on a full stomach. Crosses it out.”

But redaction also works against the reader. When, after months, Amira receives a letter from Ayoub, she pauses to call a friend who might comfort her in this alienating ritual. The letters, after all, are mostly redacted, offering neither solace nor information nor explanation:

She cannot help wondering: To what extent did Meryem’s offer come from a desire to make her life more bearable? And to what extent was it about curiosity? To what extent was Meryem looking, consciously or not, for an opportunity to dip into someone else’s raw sadness, protected by the knowledge that she would soon be safely back at home with her husband and children?

Most readers, I would think, will drop the novel in their laps with a jolt of self-recognition. What an indictment of our politics of care, which can never throw off the shackles of self-interest. What an indictment of our politics, full stop.

The chiasmus of the novel — the butterfly structure that diagonally reflects its four parts while ensuring that they never meet — serves as a reminder of fictional worlds. This is not quite mirroring; the inverted reflections I describe might make the novel seem like a trick, an Ishihara test, where we puzzle out clues. But it isn’t at all. Baker, who has written about everything from the band Belle and Sebastian to pedestrian accidents and the city of Abu Dhabi for The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, The Nation, and other outlets, brings the discriminating attention and care that he devotes to discussions of police torture in Chicago public schools, or the afterlife of Fight Club, to the intimacies here. Inspired in part by W. G. Sebald, this highly interiorized novel — despite the war-on-terror research that the work reflects — has almost nothing of Morocco, prison, Pakistan, or Rome; it is filtered entirely through the subjectivities of its characters. This is no small feat, given who the characters are. It is in that sense that Planes might be perceived as a novelist’s novel, one interested in using the psychic geographies of fiction to do things that transcend our elementary lives. In its bisected structure, pivoting from Smithfield, North Carolina, to Esquilino, Rome, the novel proposes a breach of the cordon sanitaire. Who has the right to write about the lives of others across the globe? The redaction Baker emphasizes — all the things we do not know, as we fumble around in the dark — provides an elegant solution. One marvel of the novel is the inclusion of letters that say nothing.

Planes refuses to reveal what Ayoub did or didn’t do, how or when he was arrested, and who is in the wrong. Like the clients called by the lawyer Sarah, “suffocating under the weight of every terrible thing they might be about to learn,” we wait. This refusal, the novel’s most powerful redaction, undermines both the reader, who is desperate to know exactly these things, and our typical understanding of “strategic knowledge” and “intelligence.” And yet, with little dashes of plot, it propels — yes, hurtles — us forward. By narrowing the narrative gaze to the minutiae of personhood, Baker accords a quotidian dignity unavailable on the plane of geopolitics. The novel, with its own canny intelligence, seems to know something that no one else does. In that sense, it elegantly captures how one might move through the world visible, too visible, but not seen at all.

¤

Toral Jatin Gajarawala teaches literature at New York University, in Abu Dhabi and New York.

LARB Contributor

Toral Jatin Gajarawala teaches literature at New York University, in Abu Dhabi and New York.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Make No Mistake — The US War on Terror Is Far from Finished

How security made us less secure.

Work on the Dark Side: An Inside Look at Guantanamo

Michael Rapkin, attorney for numerous Guantanamo detainees, reviews "A Place Outside the Law" by Peter Jan Honigsberg.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!