The Gravitas of the South: A Conversation with Pete Candler

Tom Zoellner talks to Pete Candler about his new book “The Road to Unforgetting: Detours in the American South, 1997–2022.”

By Tom ZoellnerApril 28, 2023

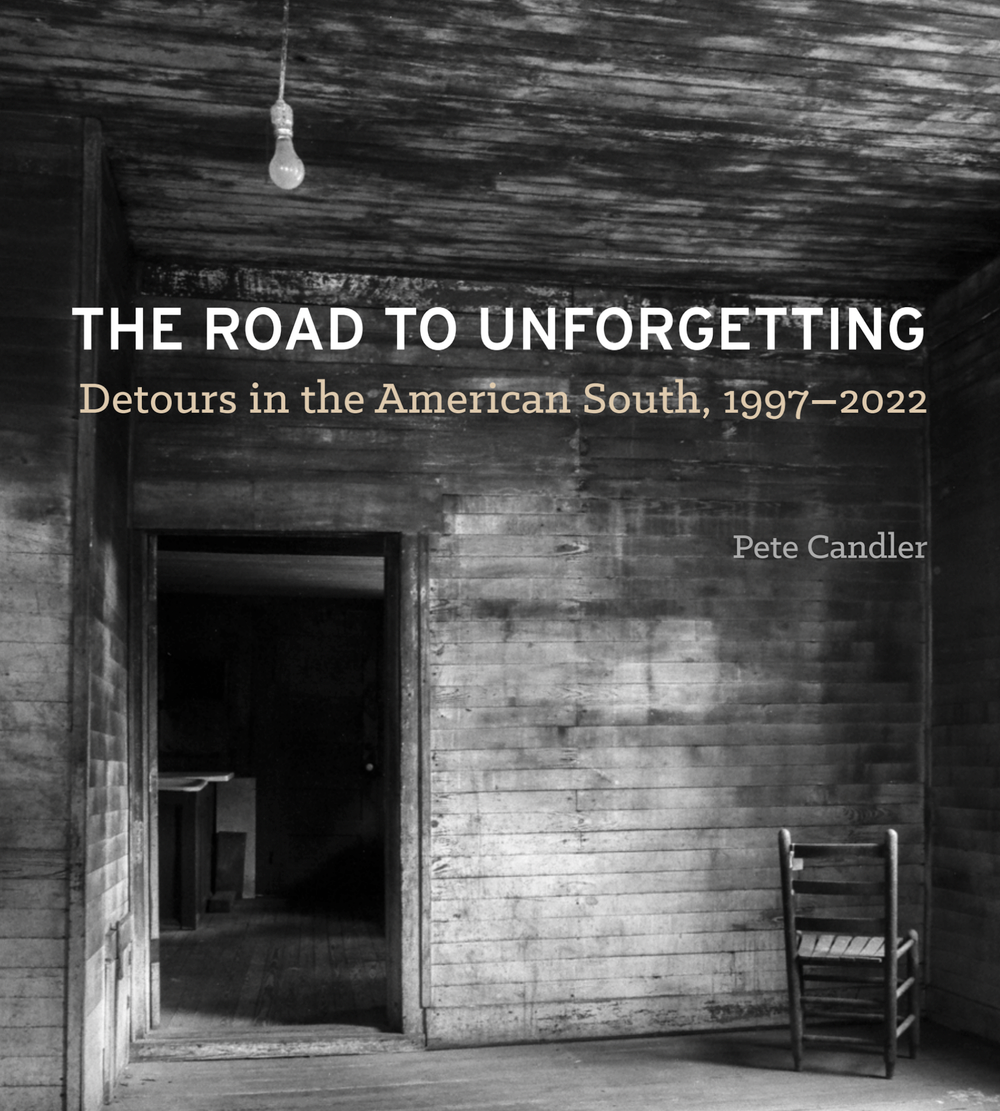

The Road to Unforgetting: Detours in the American South, 1997–2022 by Pete Candler. Horse & Buggy Press. 160 pages.

PETE CANDLER lives in the South but not always comfortably and not without a strong dose of thoughtfulness. He comes from a storied Atlanta family, with philanthropists and politicians speckled all over the family tree like persimmons. Yet he took a path through academia away from urban power and glitter that led him to a professorship in the religion department at Baylor University. He now lives in Asheville, North Carolina, with his wife and five children, where he works as a freelance writer.

Whenever he can, Candler travels into the backcountry in search of new understandings of what Flannery O’Connor called “the Christ-haunted South.” A quarter century of his photographs from those journeys are now packaged in the collection The Road to Unforgetting: Detours in the American South, 1997–2022, and they evoke a range of moods: loneliness, hope, brutality, and quiet beauty.

I met Candler in Sewanee, Tennessee, six years ago when he was contemplating a long-term literary project on what he called “A Deeper South,” portions of which have run at Los Angeles Review of Books. We spoke via email.

¤

TOM ZOELLNER: Many of the photos in this collection are of decay—a shuttered movie theater, decrepit houses, defunct soda brands, a lot of mold and rust. What drew your attention to this side of the South?

PETE CANDLER: I am sure this attention to decay has something to do with growing up in Atlanta, where there was and remains a passionate aversion to the old, much less that which is crumbling before our eyes. So much of the history of the South could be told in terms of residues, the things that are left over from an age we have so obsessively romanticized and mythologized. It’s what didn’t get airtime that interests me. The evidence of what once was, the residue more than the thing itself. And that absence, that lack, then raises other questions: Why have we forgotten this? What are we afraid of?

You revisit Plato’s Republic as a road story and also consider key elements of Christian theology. How much of your former career as a scholar of religion was emanating through these reflections of the rural South?

More than anyone else, Saint Augustine taught me the centrality of memory to the integrity of the human person. From him I learned that a healed, restored, and reintegrated memory is essential to what he—and a whole tradition before and after him—meant by “salvation,” or, in his simpler and more elegant language, salus, or “well-being.” Augustine showed me how human well-being is inseparable from a well-formed memory. The gist of all of this is something like reintegration, but if I am honest, there is no better word for what I am attempting to do in these two books and their related works than “re-membering.” And I mean that word with all of the rich theological weight and saturation with which the word was taught to me.

In the Christian tradition to which I belong, the central act of our faith is an act of remembering, in Greek an anamnesis, which literally means “unforgetting.” When we celebrate the Eucharist, we are taught to do this in anamnesis of Christ. So, everything I am attempting to do has, I think, its source in a strong belief in the importance of memory as a deeply theological act. An honest memory is corrosive of self-deception.

Anyone who’s spent time in Atlanta is going to know the name Candler, not just because of its early Coca-Cola associations but also for its prominence around town in any number of cultural and educational contexts. You’re the great-great-grandson of John Slaughter Candler, who served as a justice on the Georgia Supreme Court. How did this unique vantage point from the urban and genteel side of the South come into tension or dialogue with your experience of the poor and rural South?

Yes, the Candler name is pretty ubiquitous in Atlanta, and you’re right, not just because of Coke. Much of that is concentrated on Emory’s campus, where I was born exactly 110 years after the birth of my great-great-grandfather, John Slaughter Candler—a.k.a. “The Judge”—whose bust resides deep in the bowels of the law school. Asa’s name is everywhere, but the seminary at Emory is named for Asa and John’s middle brother, Warren, who was a prominent Methodist bishop and the first chancellor of Emory University.

Across Atlanta, there are all kinds of mementos of a wide and deep family legacy, including a building named for my grandfather that is, unsurprisingly, now a parking lot. The ubiquity of my family name in my hometown had a sort of reverse effect on me, though: I think I grew up not wanting to talk about my family. It wasn’t the sort of thing I was especially eager to draw attention to, perhaps partly out of fear that people would think everything I did was reducible to the fact that I came from a family with wealth and stature. Fair enough. On the other hand, there is also a certain tendency to overmythologize the Candler family that some of my relatives have encouraged. I wanted nothing to do with that sort of barf-inducing navel-gazing and self-congratulation, so I tended to follow the other course, just ignoring all of it. It was much later that I began to really take that family legacy more seriously and try to understand it a little better. I discovered that not really caring about your own family history was, in my case, the height of what we now call white privilege. And eventually I learned how much of a luxury it had become for me not to bother with it but to be content with a convenient mythology that required little of me and could confidently bury that history under reductive, one-name monikers like Asa, the Bishop, the Judge, the Governor, and so on.

But when my kids began learning what I was learning about my family history, they were not encumbered by all the layers and layers of intergenerational suppression and denial and willful forgetfulness. I have great admiration for what my ancestors have contributed to Atlanta, and it has in many ways motivated me to carry on the more beneficial sides of that legacy. But I also know them better now too, and to that degree, I think I can say my appreciation is invested with some hard-learned truthfulness. And my children also expressed no tendency whatsoever to want to pretend that some of their ancestors were not racist, and they seemed more well equipped to inherit a more truthful and honest story than I had.

The footnotes in this book are extraordinary. You go into great detail about the images you capture, such as an 1815 tabby structure in McIntosh, Georgia, but the images stand without narrative on the page. Curious readers must go to the back of the book to get details on what they’re looking at. Was this a conscious design choice?

It was, yes. The footnotes come at the end for a deliberate reason, and that is because, with many of my images, I was not fully cognizant of what I was looking at or photographing until long after the fact. Reflection, research, and closer examination revealed much more than I had noticed at first, so I want the reader to be able to experience that post-factum sense of revelation, as it were. I also hope for each image to be received on its own visual terms, without the addition, so to speak, of the knowledge of what they are really seeing, much in the same way as my own encounter with many of these sites on the road was often naive and innocent of any historical knowledge. Once you’ve gone through the photographs in the collection, you will find that there is a great deal more to be said about some of these pictures, which I hope will prompt the reader to go back in and look again at the particular image, now bearing a greater knowledge of what they are seeing, maybe even seeing what they missed, much as I have done.

One of the miracles of photography as an art form is its capacity to continue to deliver traces, clues, vestiges of a world that has to be slowly entered into. Saint Gregory the Great said of Scripture that, in any one sentence, it “describes a fact, [but] reveals a mystery.” He meant this as a remark about Scripture, but for me it is a provocative way of thinking about photography. I find film to be particularly powerful in its ability to disclose layers and textures to reality—indeed, literally through the medium of light-sensitive materials. But even more to the point, photography can disclose the depths of reality as such and open our eyes to the potentially infinite density of any given moment of lived existence.

You’re pretty hard on your hometown of Atlanta, describing it at one point as “a looming abyss of meaninglessness” with “no core at all.” But you also express appreciation for its “hidden gems” and the neighborhood vitality that remains in a city built on transportation—from Confederate railroads to a spaghetti junction of freeways to the busiest airport in the world. Everyone likes to poor-mouth their hometown, of course, sometimes in secret, but do you think Atlanta is fated to have this ambivalence sewn into its character?

There’s this constant tug-of-war in Atlanta between history and a progressive future that is never really worked out. The city has tried so hard for decades to either suppress or actively promote disinterest in its own history. But that history is one of the more intriguing stories among major American cities. Atlanta is famously mercurial, constantly reinventing itself to suit market tastes, so to speak. It has been in a perpetual identity crisis since General Sherman provided it with a violent opportunity to never have to ground itself in contingent reality. The leveling of Atlanta—mostly by Atlantans, far more than Sherman—serviced a self-image of a city on the move and on the make, never to be too tied down to any one thing or ideal, other than the ideal of not being too tied down to anything. This certainly crystallized during the middle of the 20th century, when the city became serious about biracial coalition-building and self-branding at the same time. It was Mayor [William B.] Hartsfield who coined the term “the City Too Busy to Hate” and also, not coincidentally, engineered the airport that is now half-named for him, and—fittingly—the busiest in the world.

Atlanta has made a career out of forgetfulness, and in that sense, it is hard to imagine a more quintessentially American city. Forgetfulness is practically our mission statement. I realize that my way of putting this may be one more way of making Atlanta exceptional, which is something we have always been doing. It may also reflect a deep insecurity. In the Olympic era, I think we were driven by a desire to prove that we could hang with the big international A-listers, like Barcelona, Paris, Tokyo. And that chip on our collective shoulder has always been there, at least in modern Atlanta. It’s there now, maybe more than ever. One motto current in town these days is that “Atlanta Influences Everything.” It’s just the latest iteration of a long trajectory of slick and skillful sloganeering designed to prove that people need to take us seriously. What makes it so interesting is that it’s not complete bullshit.

If anything, this relentless marketing has had a tendency to dull the edge of what makes Atlanta really interesting.

The inspiration for this book was a set of road trips you took with your secondary school and college friend John Hayes. Can you tell us a bit more about your friendship and what you discovered on the road with him?

None of this work would have come into being without John, whom I have known since high school. We have traveled more than just Southern back roads together: we both went into and out of short-lived but highly consequential affairs with evangelicalism and happened to end up at the same college together, where, as I have said in these pages before, we both fell for the same woman, Flannery O’Connor. Much of our friendship has been grounded in shared experiences and shared struggles attempting to come to terms with Christianity and then later with Southern history. We both grew up in big mainstream churches in Buckhead, and then drifted into an evangelical subculture at our high school that, while troubling in so many ways, at least introduced both of us to big ideas that seemed to really matter. I think what John and I discovered as we got out on the road was just how rich and surprising the region is, how mysterious and how beautiful. I don’t mean picturesque, necessarily, although it certainly has its moments. There is a gravitas to the appearance and feel of the South. It feels heavy, substantial—and so incredibly fertile.

Much of what I claim to have “seen” in these images and in these reflections is really a fruit of conversation, especially in more recent years. In earlier years, I was, as John will tell you, incorrigibly taciturn, and would go days without speaking a word. There was perhaps an element of just taking it all in, combined with a heaping tablespoon of functional depression as well, I am sure. But my ideas about the South have certainly emerged out of our friendship and are impossible for me to imagine without that relationship. I think one big part of why we’ve worked so well together as traveling partners is that we share a similar sense of humor. It is not evident in the photographs, for obvious reasons, but the nature of these trips has called for, perhaps, a good deal of levity. Over 25 years, it has been a sort of slow-and-low education in how to not take yourself so seriously, while also learning to receive your place in the story of the world with seriousness. We have giggled nonsensically over a dinner of Pabst Blue Ribbon and Pringles in Jeff Busby Park in Mississippi and had a protracted laugh at the expense of long-dead figures like General Robert Toombs and General Pierre Prudhomme, for whom we have composed counterfactual histories and a song or two.

I think the fact that these trips have been so enjoyable for me has helped me to associate the discovery of some unsavory truth, some unhealed wound, with a kind of liberatory sense, the joy of discovery with the hope of redemption, the opening of closets with the introduction of fresh air.

¤

Tom Zoellner is an editor at large for Los Angeles Review of Books.

LARB Contributor

Tom Zoellner is an editor-at-large at LARB and a professor of English at Chapman University. He is the author of eight nonfiction books, including The Heartless Stone: A Journey Through the World of Diamonds, Deceit, and Desire (2006), Uranium: War, Energy, and the Rock That Shaped the World (2009), The National Road: Dispatches From a Changing America (2020), Rim to River: Looking into the Heart of Arizona (2023), and Island on Fire: The Revolt That Ended Slavery in the British Empire, which won the 2020 National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction and was a finalist for the Bancroft Prize in history.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Alternate Atlanta: Michael Bishop’s “The City and the Cygnets”

Doug Davis explores the Urban Nuclei of Michael Bishop's "The City and the Cygnets."

Entering the Prism of Family: On Maud Newton’s “Ancestor Trouble”

Lesley Heiser explores Maud Newton’s investigation of ideas of ancestry, genealogy, and her own family in “Ancestor Trouble.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!