Alternate Atlanta: Michael Bishop’s “The City and the Cygnets”

Doug Davis explores the Urban Nuclei of Michael Bishop's "The City and the Cygnets."

By Doug DavisAugust 27, 2022

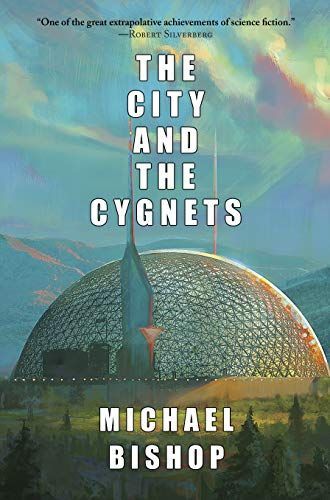

The City and the Cygnets by Michael Bishop. Kudzu Planet/Fairwood Press. 466 pages.

MICHAEL BISHOP’S The City and the Cygnets is an alternate history of the city of Atlanta. Bishop’s Atlanta does not grow to become the American South’s largest sprawling metropolitan area. Instead, the city encases itself within a giant dome big enough to contain the entire population of the state of Georgia, and the city’s residents remain trapped inside their dome for almost a century. Bishop’s novel is an impressive achievement of speculative world-building: his domed Atlanta is a technological marvel straight out of Buckminster Fuller’s wildest geodesic dreams; his descriptions of abandoned Georgia highways and suburbs choked in kudzu are haunting and unforgettable; and his cat-eating space aliens, “the Cygnets,” are truly eerie. Yet as memorable as these fantastic sights are, The City and the Cygnets succeeds mostly because its author never loses sight of what all cities, domed and otherwise, are really made of: the people who live in them.

The City and the Cygnets is a multigenerational epic loosely organized around the Cawthorn family. Each generation plays a small part in the domed city’s history. Parthena Cawthorn was born before the Atlanta dome was raised and spends her final days as the happy subject of the city’s progressive geriatric healthcare system. Her granddaughter Georgia is born inside the dome during less enlightened times, and after joining a workers’ revolt, she is murdered by the city’s government. Georgia’s son Julian grows up to be a newspaper reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution who helps to bring both the alien Cygnets into the city and the Atlanta dome down.

These characters all live through times that are at once trying and extraordinary. Like many alternate histories, The City and the Cygnets contains a chronology: Bishop’s covers the major events between the years 1968 (the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.) and 2075 (when the dome is dismantled). In her introduction to The City and the Cygnets, author Kelly Robson identifies the novel’s Jonbar point — an event that pushes history into an alternate timeline — as the assassination of Alberta Williams King, the mother of Martin Luther King, in Ebenezer Baptist Church in 1973 (in reality, she was killed in June 1974). (Atlanta history will repeat itself in the novel’s year of 2029 when “evangelist-reformer” Carlo Bitler is assassinated, an event that rings for decades throughout the city’s racially fraught future history and that launches the novel’s first chapter.) From 1973 onwards, Bishop’s history increasingly diverges from our own. The Cold War does not end with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 but instead continues for a fifth decade; the still-extant Soviet Union wages a punishing conventional war of attrition with China; the countries of Western Europe, guided by a “Pan-European Ecumenical Movement,” unite as New Free Europe; and the United States, riven by internal political turmoil and committed to a doctrine of “Preemptive Isolation,” starts to fall apart.

Between 1994 and 2004, American isolationism hypertrophies in a spectacular way as the fading states of the union construct 25 giant domed “Urban Nuclei” safely sealed off from environmental and social contamination. The 25 domes form a new political entity called the North American Urban Federation, a loose alliance of politically and economically independent city-states connected by a rarely used underground rail network. To populate the “Atlanta UrNu,” four “Evacuation Lotteries” are held that move all of Georgia’s rural residents inside the dome. “Surprisingly,” the narrator of the novel’s prelude observes, “most of those selected chose to obey their summons — perhaps because they were delighted to have won a lottery or half-panicked by realizing that someone had deemed an evacuation from the countryside crucial to their preservation.” In 2004, the United States officially ceases to exist, and all the citizens of Georgia have been “evacuated” into the Atlanta UrNu. Trapped under their dome, Atlantans burrow downwards, constructing a giant multilevel catacomb in which most of them live. The novel begins in the year 2035, by which point most Atlantans have come to believe that the world outside is a dangerous wreck, and the dome is the only thing keeping them safe from it.

They are all mistaken.

People come and go from the dome all the time. The outside world is not dangerous at all; beyond the dome, fields of kudzu cover abandoned suburban sprawl, turning it into a “deformed landscape” of “green temples, kudzu arabesques, pagodas to the gods of rampant fertility.” The few remaining Black residents of rural Georgia have moved into grand plantation homes and established farms in the ruins of small towns such as Toombsboro, trucking fresh produce into the city on old interstate highways with trucks running on homegrown biodiesel. Unbeknownst to most Atlantans, the city regularly sends out “resources-reclamation” teams to the country to “reclaim […] people with desirable technical skills or influential relatives in the city.” Meanwhile, New Free Europe has taken up the space program the United States abandoned, built a base on the moon, and is sending faster-than-light spacecraft to distant stars and making first contact with space aliens. Life in the Atlanta UrNu falls increasingly under the control of its insular, authoritarian, and theocratic government, which restricts access to both pre-dome culture and most knowledge of the world outside the Urban Nuclei.

While Bishop’s alternate history can be read as a metaphor for current events, The City and the Cygnets is not a new story. Its eight sections were first published independently over the course of the 1970s in magazines (and as the short novel A Little Knowledge), and all of these were part of what Bishop called his “Urban Nucleus Cycle” (or “UrNu Cycle” for short). Recently, Bishop worked with the Kudzu Planet imprint of Fairwood Press to publish a revised version of the entire UrNu Cycle as the single complete novel The City and the Cygnets. He polished the cycle’s style and updated its technologies, replacing the tape loops of the 20th century with the computer screens of the 21st.

The UrNu cycle was unique when it was first published in the 1970s because it was set in the American South. The South has a long and distinctive regional literary tradition, but it does not have a long or distinctive science fiction tradition. Indeed, Michael Bishop is the first author in the history of science fiction to write about a domed Southern city. Bishop uses this new setting to tell a new kind of tale: a fully Southern, future-historical, multigenerational family epic set in a domed city that should never have been built at all.

The influence of Southern literature can be felt strongly throughout the UrNu cycle. Within it, the attentive reader will find Mark Twain’s cutting wit, William Faulkner’s modernist style, Flannery O’Connor’s grotesque characters, and James Dickey’s landscape imagery, among much else. The devouring weeds and junkyards Dickey lyricizes in “Kudzu” and “Cherrylog Road” now cover all of Bishop’s Georgia. O’Connor’s “Displaced Person,” in turn, has become a “Displaced Alien” named “Cygnor the Cygnet,” a refugee from an exploding star system who has newly moved into Atlanta. Cygnor is the first alien to arrive in the Atlanta UrNu from another star (there will be others), and soon he is put on display in the middle of the Dixie-Apple supermarket down on catacomb level four to greet the people of Atlanta. The displaced alien watches silently as the Dixie-Apple’s shoppers are handcuffed to carts that comically hurry around a track. Cygnor the Cygnet disrupts life in domed Atlanta much as the displaced person Mr. Guizac disrupts life on Mrs. McIntyre’s farm in O’Connor’s tale, and soon the shopping carts in the Dixie-Apple are running off the rails because of his presence. The cygnet then gets his own Faulknerian chapter titled “Cygnostik Stream-of Consciousness,” which consists of one single-spaced sentence that represents for two-and-a-half pages how a Cygnet perceives life in its suite on the top floor of the Atlanta Hyatt hotel.

Another major influence on the UrNu cycle comes from Bishop’s science fiction contemporaries Robert Silverberg and Thomas M. Disch. As he writes in his afterword, Bishop was still a self-described “struggling, aspiring science fiction writer” when he started writing the UrNu Cycle. He based his domed Atlanta on the megastructural “Urban Monads” of Robert Silverberg’s 1971 novel The World Inside, 1000-story towers whose huge floors contain entire cities full of billions of citizens who never leave them. To assemble his UrNu stories into cycle form, Bishop used the model of another work of contemporary urban science fiction that combines long and short stories, Thomas M. Disch’s 1974 novel about a future New York in decline, 334. In 334, Disch yokes together the disparate stories of the 21st-century residents of a public housing project at 334 East 11th Street. Silverberg’s Urban Monads and Disch’s public housing project imprison their characters, define the limits of their lives, and destroy their humanity.

Unlike Silverberg’s monadic future humans and Disch’s New Yorkers, Bishop’s Atlantans are not defined or destroyed by the city that contains them. Instead, they create new kinds of human connections amidst the city’s high-tech wonders, resist its increasingly autocratic rule, and find sublime pleasures in even its most grotesque urban spaces.

Science fiction often features imagery that is by turns technologically sublime and grotesque. Science fiction’s imagery of the technological sublime celebrates technoscientific rationality and human prowess by representing built things that are so big they shock the mind. Science fiction’s grotesque imagery counters the genre’s experience of the sublime, exposing the limits of technoscientific rationality and human control. Where the sublime in science fiction directs attention ever upward and outward to bigger and bigger vistas and things (like giant domes), the grotesque in science fiction refocuses attention on the earth and the human body.

Atlanta’s unthinkably huge dome evokes the technological sublime, but Bishop does not let that dome stand unquestionably as a triumph of reason. He counters the dome with the city’s catacomb, a tomb-like space whose perpetually red-lit corridors lead to waste plants where deceased human bodies are converted into drinking water and even cosmetics. The catacomb subverts the technologically sublime thrill of Atlanta’s dome, showing the human cost it takes on those who built and live in it. It is full of broken bodies, such as that of “the paraplegic beggar/guard MeeJee Stone [who] sat sleepily astride his rollerboard holding a sub machine gun” in the depths of catacomb level nine. MeeJee Stone is one of the dome’s many human costs, losing both his legs “in a demolition accident with the McAlpine Company,” the company that built the dome.

The catacomb can be a grotesque place, but it is also an exciting and vital place where Atlantans can find underground art and culture and new kinds of technologically sublime pleasures. The impoverished level-nine-dwelling courier Georgia Cawthorn describes the unique thrill of roller-skating at high speed through the underground city’s vast corridors as follows:

Down here, we’re volplaning [“what an airplane does when its motor quits”] […] whole body slipping through air like an arrow, head up and flat out […] Soulplaning, we call it, when everything smooth and feathery, and it makes living sweet. It beats liquor, new peaches, and a lovin tongue, it beats most anything I can think of. Doing it, you forget bout almost everything, including how nobody see the Moon no more. That’s true soulplaning.

The technologically sublime thrill of speeding like an airplane can now be experienced, ironically, in only one place in the Atlanta UrNu — underground — and by only its most downtrodden citizens. However, the pleasures of soulplaning are so total that they — and not the dome — give life for those trapped underground a unique, even privileged form of meaning.

Conversely, the ruling classes who live in Atlanta’s surface towers directly under the technologically sublime dome produce the UrNu Cycle’s most grotesque feature: the freakish “hoisterjack” subculture composed entirely of “the adolescent sons of the wealthy and enfranchised” whose members delight in terrorizing the city’s population “with mad gestures and mad nylon-distorted faces.” Just as life under Atlanta provides its own sublime pleasures, life on the city’s surface breeds its own grotesques. The hoisterjacks descend from their elite towers and “leap out of the darkness of the catacombs, to cling to the crystalline faces of lift-tubes, and to scream like bloodthirsty hyenas as they press their misaligned features against them.” The hoisterjacks may be the privileged residents of Atlanta’s massive tribute to technoscientific reason, its giant dome, but their suicidal, terroristic actions defy reason entirely.

“From the beginning,” Bishop writes in the afterword to The City and the Cygnets, “the Urban Nucleus series was a thought-experiment fantasy, cast in the science-fiction mode, one meant to entertain as its young author struggled to dramatize something affirmative about the human spirit under even the most repressive conditions.” Newly revised for a 21st century readership, Bishop’s epic alternate history continues its work of affirming the value of the human spirit. The Cawthorns’ family spirit endures hoisterjacks and a cruel government that turns against it. In the end, it outlives the dome itself.

The City and the Cygnets is a major narrative achievement within the history of science fiction, written by one of the field’s most skillful and humane writers. For those reasons alone, it is recommended for all fans and students of the genre. The drama at the cycle’s core, though, issues from the powerful wellspring of Southern literature, whose authors have long explored how the human spirit can endure even when it fails itself. Admirers of Southern literature will find that the UrNu Cycle offers a fresh and surprising new vision of a familiar region. Beyond genre and region, Bishop’s alternate history of Atlanta is recommended for all readers who seek an affirmation of the human spirit during times such as ours.

¤

LARB Contributor

Doug Davis is professor of English at Gordon State College in Barnesville, Georgia, where he teaches literature and writing. He is the author of numerous essays on topics ranging from the extinction of the dinosaurs and the United States’ culture of nuclear threat to the technological sublime in the literature of the American South and the technoscientific foundations of Flannery O’Connor’s storytelling.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Man in the Maze: A Conversation with Robert Silverberg

A Grand Master talks about his career and the evolution of the SF marketplace since the 1950s.

An Uneven Showcase of 1960s SF

Rob Latham reviews the new Library of America set of 1960s SF novels.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!