FREUD TOLD US that one of the most unsettling effects for human ontology is to be confronted by a machine that comes to life. In this, he was but echoing what was already a century-long anxiety about the limits and definitions of the human since the beginning of the machine age. Rupert Sanders’s new film Ghost in the Shell, based on the 1995 cult classic anime of the same name by Mamoru Oshii, based on the manga by Shirow Masamune, and following a long line of cinematic cyber-fiction from Blade Runner to Ex Machina, extends this apprehension about the animation of the inanimate and asks all of the expected (and, dare I say, tired) questions: What makes a human human? Is consciousness the same as the soul? Is there a ghost in the machine? Is artificial intelligence an enhancement or an erasure of the human? What happens to the human element when the brain gets reduced to a series of electrical impulses, and, conversely, along a more sentimental line, can machines have feelings, too?

Raising these questions has become a convention of the cyber-fiction genre; so, too, has the deployment of femininity and racial otherness as gratuitous and exotic titillation. Reviews of Sanders’s film have already noted the voyeuristic pleasures afforded by a “naked” Scarlett Johansson, who plays Major Motoko Kusanagi, an augmented cybernetic cop who is not shy about exposing her wholly synthetic body. Many have chided the movie for its appropriative uses of Asiatic things and persons as exotic decor, and all seem to agree that the casting of Johansson as Kusanagi was a form of commercial “whitewashing,” if not downright whiteface. But a film like Ghost in the Shell should raise questions for us about the relationship between surface and embodiment, especially what that relationship really entails for raced and gendered subjects.

Ghost in the Shell, along with the genre of cyberpunk with its techno-Orientalism, itself a reboot of 19th-century Orientalism, gives us the opportunity to consider an alternative logic of American racial embodiment. Dichotomies like authenticity versus artificiality, interiority versus surface, ghost versus shell, organic humanness versus synthetic assemblage simply do not help us address the uncanny materialization of race and gender. The peculiar thing about “Asiatic femininity” in the Western racial imagination is that it has never needed the biological or the natural to achieve a full, sensorial, agile, and vivid presence:

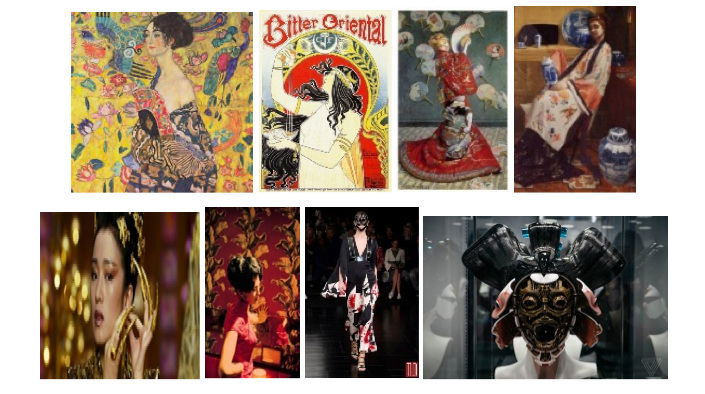

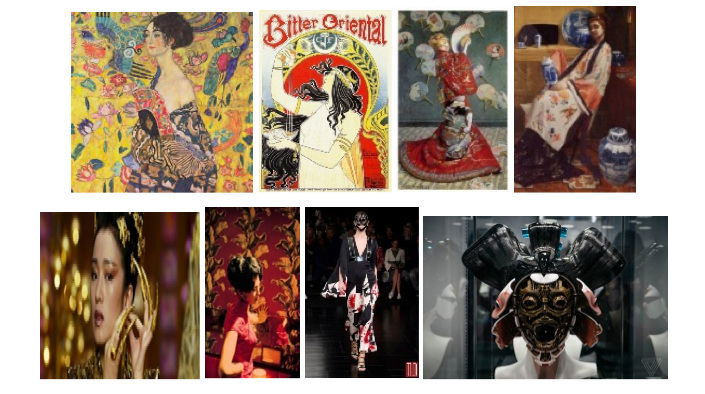

The conflation of Asiatic femininity and artificiality reaches from Plato through Oscar Wilde and can be seen in Art Nouveau, French Symbolism, all the way up to wide-ranging versions in the 21st century. Asiatic femininity has always been prosthetic. The dream of the yellow woman subsumes a dream about the inorganic. She is an (if not the) original cyborg.

It is easy to mourn the loss of humanity in a figure like this or, conversely, to celebrate its triumphant posthumanism, but it is much harder — and, I would argue, much more urgent — to dwell with the discomfort of undeniable human alterity, a figure who does not let us forget that the human has always been embroiled with the inhuman well before the threat of the modern machine. In this light, racial logic as this strange embodiment-that-is-also-not-enfleshment haunts Ghost in the Shell, playing itself out compulsively on the surfaces of the film: in the flickering holograms of the mise-en-scène, on the hygienic surfaces of the Frankensteinian lab, and on the skin of our heroine. It is not a coincidence that the most visually arresting and most philosophically suggestive element in the film is the Major’s epidermis: an arresting combination of resilient matter and willful transparency; seamed yet seamless; a unified collation of fragmented and variegated nudes; a bareness that is also armor. The Major’s supra-human and sartorial skin exemplifies pure impenetrable technology, but it also carries the unseen, porous, and fractured history of human labor, by which I do not mean the delicate hands of her scientist-surgeon creator but the laboring race-body underlying the slave logic of the cyborg. Thus the very surface of Johansson/Major’s white, inorganic, impeccable, and implacable skin, precisely as cladding, enacts, counterintuitively, a “deep dive” into Asiatic femininity. She is the 21st-century technological shell encasing the traumatic kernel of Euro-American imperialism and racial history. (Let us not forget that the Major is the product/daughter of an American industrial giant heralding high-tech progress in a “corporate conglomerate-state called ‘Japan.’”)

If one of the global inhuman humans that emerged out of Western imperial history was the Chinese coolie (a male laboring body mythologized as infinitely capable of enduring pain, mechanical, an ideal laborer), and if one of the other inhuman human figures arising out of the 19th century was the Oriental woman (a female, decorative, disposable toy for leisure), then we can think of the Major as the merging of both: a body of labor and numb endurance, but also a smooth beauty that bears the lines of its own wreckage, a delicacy that is also impermeable and insensate. Throughout most of the film, the protagonist played by Johansson is simply named the Major; Sanders suppresses for most of the film the original anime character’s full (and explicitly Japanese) name. This may abet the whitewashing, but it also has the opposite effect of punching up the big reveal at the end — the disclosure that Major’s “white” body has been playing host to Kusanagi’s “Japanese” brain — by fulfilling a racial logic that has been implicit all along.

In the original anime series, the most chilling philosophic proposition is not that machines and cyborgs can be hijacked but that human consciousness can be hacked. In Sanders’s film version, the pathos of the human as vulnerable-yet-mechanical is augmented by precisely the spectral evocation of Asiatic femininity, the imaginary engine that switches between the thingness of persons and the personness of things. The film may tell a cautionary tale about how people have been turned into things; consider this memorable line spoken to our cyborg heroine: “They did not save your life; they stole it.” But the history of Orientalism in the West is not just a history of objectification but also a history of personification: the making of personness out of things. This Non-Person, normally seen as outside of modernity and opposite to organic human individualism, actually embodies a forgotten genealogy about the coming together of life and nonlife, labor and style, which conditions the modern conceit of humanness.

As the scientists in Ghost in the Shell keep telling us, the Major is the great hope, the “success story,” the Eve for the future. Repeatedly touted as unique, though we discover the opposite, the Major stands as a singularity that is serial: a shell born out of many other shells. When the Major looks into the face of a geisha-robot-assassin in a barely disguised mirror scene, her comrade Batou (Pilou Asbæk) is quick to assure her of a distinction, “You are not like that.” But we suspect that what is being disavowed here is precisely the complex and messy interpenetrations of race, gender, and machine. Being a cyborg and a hybrid being, the Major is exactly like the robot: Asiatic, other, alien. And this condition of otherness is, paradoxically, the alibi for, and the residue of, her humanity. Race and femininity are the supplements that enable this toggle between the human and the inhuman to emerge.

We have arrived at a double-edged sword: racial and gender differences entail a history of profound dehumanization; at the same time, they have also provided the most powerful and affective agents for humanizing the dreams of synthetic inventions.

What is inside the machine? The yellow woman: the ghost within the ghost. The biographical revelation at the end of Ghost in the Shell is but a literalization of this insight. This is also why the Asiatic woman can play double roles: simultaneously atavistic (the geisha, the slave girl) and futuristic (the automaton, the cyborg). The artificiality of Asiatic femininity is the ancient dream that feeds the machine in the heart of modernity.

Raising these questions has become a convention of the cyber-fiction genre; so, too, has the deployment of femininity and racial otherness as gratuitous and exotic titillation. Reviews of Sanders’s film have already noted the voyeuristic pleasures afforded by a “naked” Scarlett Johansson, who plays Major Motoko Kusanagi, an augmented cybernetic cop who is not shy about exposing her wholly synthetic body. Many have chided the movie for its appropriative uses of Asiatic things and persons as exotic decor, and all seem to agree that the casting of Johansson as Kusanagi was a form of commercial “whitewashing,” if not downright whiteface. But a film like Ghost in the Shell should raise questions for us about the relationship between surface and embodiment, especially what that relationship really entails for raced and gendered subjects.

Ghost in the Shell, along with the genre of cyberpunk with its techno-Orientalism, itself a reboot of 19th-century Orientalism, gives us the opportunity to consider an alternative logic of American racial embodiment. Dichotomies like authenticity versus artificiality, interiority versus surface, ghost versus shell, organic humanness versus synthetic assemblage simply do not help us address the uncanny materialization of race and gender. The peculiar thing about “Asiatic femininity” in the Western racial imagination is that it has never needed the biological or the natural to achieve a full, sensorial, agile, and vivid presence:

The conflation of Asiatic femininity and artificiality reaches from Plato through Oscar Wilde and can be seen in Art Nouveau, French Symbolism, all the way up to wide-ranging versions in the 21st century. Asiatic femininity has always been prosthetic. The dream of the yellow woman subsumes a dream about the inorganic. She is an (if not the) original cyborg.

It is easy to mourn the loss of humanity in a figure like this or, conversely, to celebrate its triumphant posthumanism, but it is much harder — and, I would argue, much more urgent — to dwell with the discomfort of undeniable human alterity, a figure who does not let us forget that the human has always been embroiled with the inhuman well before the threat of the modern machine. In this light, racial logic as this strange embodiment-that-is-also-not-enfleshment haunts Ghost in the Shell, playing itself out compulsively on the surfaces of the film: in the flickering holograms of the mise-en-scène, on the hygienic surfaces of the Frankensteinian lab, and on the skin of our heroine. It is not a coincidence that the most visually arresting and most philosophically suggestive element in the film is the Major’s epidermis: an arresting combination of resilient matter and willful transparency; seamed yet seamless; a unified collation of fragmented and variegated nudes; a bareness that is also armor. The Major’s supra-human and sartorial skin exemplifies pure impenetrable technology, but it also carries the unseen, porous, and fractured history of human labor, by which I do not mean the delicate hands of her scientist-surgeon creator but the laboring race-body underlying the slave logic of the cyborg. Thus the very surface of Johansson/Major’s white, inorganic, impeccable, and implacable skin, precisely as cladding, enacts, counterintuitively, a “deep dive” into Asiatic femininity. She is the 21st-century technological shell encasing the traumatic kernel of Euro-American imperialism and racial history. (Let us not forget that the Major is the product/daughter of an American industrial giant heralding high-tech progress in a “corporate conglomerate-state called ‘Japan.’”)

If one of the global inhuman humans that emerged out of Western imperial history was the Chinese coolie (a male laboring body mythologized as infinitely capable of enduring pain, mechanical, an ideal laborer), and if one of the other inhuman human figures arising out of the 19th century was the Oriental woman (a female, decorative, disposable toy for leisure), then we can think of the Major as the merging of both: a body of labor and numb endurance, but also a smooth beauty that bears the lines of its own wreckage, a delicacy that is also impermeable and insensate. Throughout most of the film, the protagonist played by Johansson is simply named the Major; Sanders suppresses for most of the film the original anime character’s full (and explicitly Japanese) name. This may abet the whitewashing, but it also has the opposite effect of punching up the big reveal at the end — the disclosure that Major’s “white” body has been playing host to Kusanagi’s “Japanese” brain — by fulfilling a racial logic that has been implicit all along.

In the original anime series, the most chilling philosophic proposition is not that machines and cyborgs can be hijacked but that human consciousness can be hacked. In Sanders’s film version, the pathos of the human as vulnerable-yet-mechanical is augmented by precisely the spectral evocation of Asiatic femininity, the imaginary engine that switches between the thingness of persons and the personness of things. The film may tell a cautionary tale about how people have been turned into things; consider this memorable line spoken to our cyborg heroine: “They did not save your life; they stole it.” But the history of Orientalism in the West is not just a history of objectification but also a history of personification: the making of personness out of things. This Non-Person, normally seen as outside of modernity and opposite to organic human individualism, actually embodies a forgotten genealogy about the coming together of life and nonlife, labor and style, which conditions the modern conceit of humanness.

As the scientists in Ghost in the Shell keep telling us, the Major is the great hope, the “success story,” the Eve for the future. Repeatedly touted as unique, though we discover the opposite, the Major stands as a singularity that is serial: a shell born out of many other shells. When the Major looks into the face of a geisha-robot-assassin in a barely disguised mirror scene, her comrade Batou (Pilou Asbæk) is quick to assure her of a distinction, “You are not like that.” But we suspect that what is being disavowed here is precisely the complex and messy interpenetrations of race, gender, and machine. Being a cyborg and a hybrid being, the Major is exactly like the robot: Asiatic, other, alien. And this condition of otherness is, paradoxically, the alibi for, and the residue of, her humanity. Race and femininity are the supplements that enable this toggle between the human and the inhuman to emerge.

We have arrived at a double-edged sword: racial and gender differences entail a history of profound dehumanization; at the same time, they have also provided the most powerful and affective agents for humanizing the dreams of synthetic inventions.

What is inside the machine? The yellow woman: the ghost within the ghost. The biographical revelation at the end of Ghost in the Shell is but a literalization of this insight. This is also why the Asiatic woman can play double roles: simultaneously atavistic (the geisha, the slave girl) and futuristic (the automaton, the cyborg). The artificiality of Asiatic femininity is the ancient dream that feeds the machine in the heart of modernity.

¤

LARB Contributor

Anne Anlin Cheng is a professor of English at Princeton University and 2023–24 Scholar in Residence at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Her book of personal essays, Ordinary Disasters, is forthcoming from Alfred A. Knopf in 2024.

LARB Staff Recommendations

You Can’t Have Me: Feminist Infiltrations in Object-Oriented Ontology

Rebekah Sheldon on "Object-Oriented Feminism."

The Modest Problem of Death: On Mark O’Connell’s “To Be a Machine”

Nicole Clark on transhumanism and Mark O'Connell's "To Be a Machine."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2017%2F04%2FCheungGhostintheShell.png)