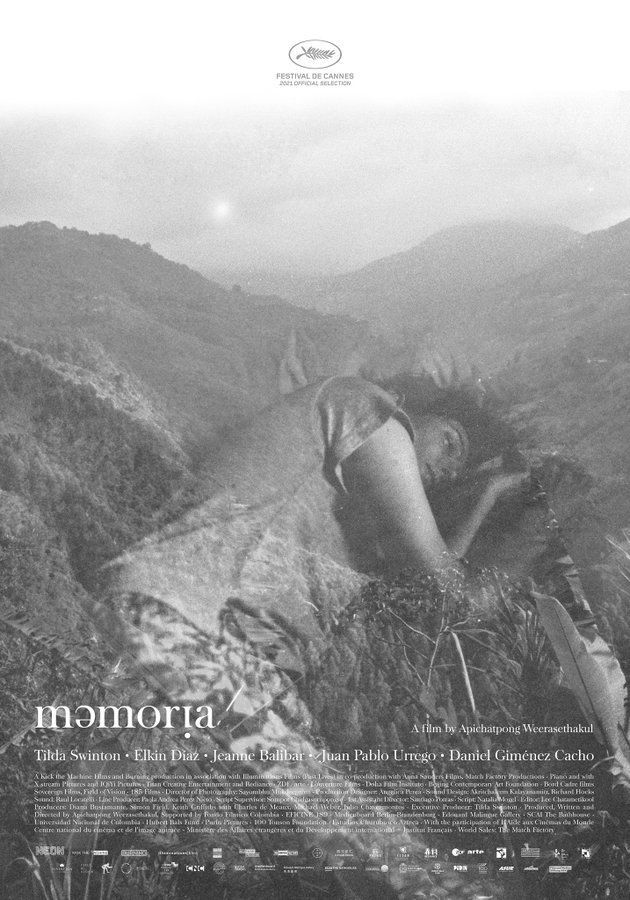

The Bogotá of “Memoria”: Translation and Contemplation 2,600 Meters Closer to the Stars

Juan Camilo Velásquez analyzes how Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s “Memoria” constructs the space of Bogotá.

By Juan Camilo VelásquezSeptember 1, 2022

“IT’S LIKE A RUMBLE from the core of the earth,” says Jessica (Tilda Swinton) as she struggles to describe the mysterious sound that has haunted her for days. Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria opens in a quiet bedroom, filled with the cold light of Bogotá’s dawn, when the peace is suddenly interrupted by a loud bang. Jessica wakes up, startled. The car alarms in a nearby parking lot are triggered into a symphonic reverie. Like an aural phantom, the sound continues to follow Jessica, appearing unannounced and seemingly only banging on her eardrums. “It’s like an enormous concrete ball slamming into a metal background, surrounded by seawater,” she tells Hernán (Juan Pablo Urrego), a sound engineer attempting to reproduce her sound. “How big is the ball?” he asks. “Bam!” she replies before apologizing for the difficulty of the task she’s bestowed upon him. “More metallic … earthier … rounder,” Jessica explains, scrambling to find adjectives that approximate her sound.

Using a bank of movie sound effects, Hernán endeavors to match the precise texture, timbre, and bass of her sound. When it seems like they finally replicated it, Jessica asks for a bit more bass, but Hernán explains that bass will sound completely different whether it is heard in a movie theater, in a music studio, or out of a pair of headphones. Sound is not independent of space but is a product of it. Relaying one’s auditory impressions is so difficult because they are determined by space, and Jessica’s sound is inextricably entangled with her foreign relationship with Bogotá. A place is not just the setting for one’s life story; it is an active participant in one’s narrative and a shaper of one’s subjectivity.

In this scene, Swinton and Urrego speak to each other deliberately and meditatively, making room for the loud grumble of silence that reverberates in the soundproofed music studio. Oscillating between cautious description and irascible passion, the actors capture the tongue-tied clumsiness of translating sound into words, thereby displaying the limits of interpersonal communication and artistic creation.

Memoria is an unexplainable film, not because I lack the vocabulary but because explanation is beside the point. Combining surreal fable with slow scenes of everyday life, Weerasethakul’s films, which include Tropical Malady (2004), Syndromes and a Century (2006), and Cemetery of Splendor (2015), play with the meditational capacities of cinema. That is not to say that Weerasethakul entirely ignores plot or story; the director carefully crafts atmospheres that inevitably put narrative in the back seat.

Memoria is no different. Many of the film’s scenes float free from the strictures of linear plot development, jumping around temporalities and registers. Rainy and sunny landscapes follow one another in a confusing daze, while various scenes are drawn out and aimless, resembling more a panorama than a plot beat. Jessica, the protagonist, offers little by way of backstory other than that she’s Scottish and visiting her sister in Bogotá. Like a poorly assembled guitar succumbing to entropy, as shown in a scene in the first half of the film, the contours of Jessica’s subjectivity are becoming undone. But even though she thinks she is going insane, because no one else hears her sound, Jessica does not retreat into herself. If anything, she becomes even more curious about Colombia’s ancient and modern past; she spends the rest of the movie surveying, ascertaining, and snooping on the whispers that others ignore.

Swinton herself has described Jessica as a “predicament” rather than a character, but it also seems that she is a stand-in for the director’s experience and for a universal feeling of geographical and semantic disarticulation. Before Memoria, Weerasethakul and Swinton had been planning a collaboration for years, but they wanted a location equally foreign to both, so Thailand was out of the question. In 2017, the director was visiting Colombia when he began suffering from intense symptoms of exploding head syndrome (EHS), an affliction similar to Jessica’s. “I was so attracted to the architecture in Bogotá — it’s so massive and is something new to me,” he told Nobuhiro Hosoki in an interview. “It reminded me of this image that I saw in the exploding head [syndrome], when I see the geometric pattern, this flash of square or circle. So I also stick with this circle idea quite a lot in the film.”

An architect by training, Weerasethakul has always displayed interest in the built environments surrounding his characters in rural and urban Thailand. When filming Bogotá, he goes outside. Attempting to externalize his internal affliction, he focuses on the exteriors, facades, and skins of the city’s buildings. “When you’re in Bogotá, it feels like it’s breathing: it’s like you’re in the belly of an animal,” he told Cinema Scope. And having grown up in Bogotá, I know exactly what he means. The city is located high up on a plateau of the Colombian Andes, “2,600 meters closer to the stars,” as the city slogan once proudly proclaimed, even though that same altitude makes many visitors sick. Everywhere in the city, you are likely to be greeted by an enormous mountain range; elusive yet conspicuous, it traps its eight million denizens and demands their attention. Nothing can escape its eye, and it never leaves one’s range of vision. But with claustrophobia also comes a sense of comfort, and while the Eastern Hills might seem all too powerful, they also nestle and comfort you.

There is no one more attuned to the cavernous spatiality of Bogotá than architect Rogelio Salmona. Born in Paris in 1929, Salmona’s family moved to Bogotá before the Second World War and settled in Teusaquillo, a neighborhood known for its red-brick, faux-Tudor houses. When violence erupted during El Bogotazo, Salmona moved to Europe, where he studied and worked for Le Corbusier. After a decade in the old continent, he returned to his adoptive city, ready to paint it red. Indeed, Salmona is famous for his widespread use of red brick, a local material that had long been disdained as a mere cheap substitute for stone. While he was influenced by European ideas from Le Corbusier, Pierre Francastel, and the Arabic architecture of Andalusian Spain, Salmona wanted to develop a local architectural style, stating that

Latin America, after having created the architecture of others, never its own […] is once more looking inward and facing its own reality. Both public and private precincts must again become places of communication and encounter, enriched by natural elements like water, sound, wind, shadows.

Blending cosmopolitanism and localism, Salmona’s work was aware of international trends, but its ears remained pressed to its immediate surroundings.

Rogelia Salmona built one of Bogotá’s most recognizable and influential architectural works: Torres del Parque, a private residential complex made up of three towers on the northern edge of the Parque de la Independencia, at the foothill of the iconic Monserrate hill. Rising from a podium that overlooks the Plaza de Toros de Santamaría — a bullfighting ring built in the Mudéjar revival tradition of the 1930s — each tower has a curved profile that spirals upward in a planimetric fan. The stepped balconies shorten as they ascend, which, coupled with the substantial volume of the bases, gives the towers a mountainous appearance.

The simple, unadorned crimson brick skins shine against the fickle sun, the profusion of jutting edges and protruding corners creating a sculptural form that imitates the texture of the city and nearby mountains. Architecture scholar Ricardo Castro writes, “If what predominated [in Bogotá at that time] were orthogonal, prismatic volumes, Salmona would recur to third grade curves to evoke geometrically the circles and the inverted, hollow cone of the bullring.” On the ground, there are a series of brick promenades, terraces, and outdoor spaces that trace the curvilinear geometry of the bullring, and which, unlike most private residencies in the city, are open to the public. An innovative project for its time, Torres del Parque was influenced by the work of German architect Hans Scharoun, but it was also profoundly imbricated with Bogotá’s architectural history and natural landscape.

When I saw the blueprints for Torres del Parque, I was immediately reminded of the jagged, zigzagging light auras I see when I get migraines. While I obviously knew this was a coincidence, there was something curious about this externalization of my internal woes. It made me realize that even as Salmona’s work explicitly confronts the connections between architectural ideals and local realities, he also enacts a gesture that recalls Memoria’s musings on translation. Salmona is not merely in conversation with Bogotá; he is also repeating its lines, trying to capture its metallic, earthy, round tones in manmade material. Mimicking the Eastern Hills, Salmona’s towers organically rise to the sky, blanketing and engulfing the city beneath with their peaky shadows. The outdoor paths are punctuated by steep peaks, peaceful terraces, and treacherous stairways, all covered in wilted leaves and footprints. Torres del Parque reconstructs the experience of living in the city, which doesn’t mean it merely replicates its shapes. Rather, through alchemy or skill, Salmona invented architectural forms that conjure the same sensations as local nature. The architect accomplished a herculean task that keeps lesser artists up at night: he transformed an indescribable, embodied experience into an aesthetic object.

How does an artist transform feeling into artwork? At the heart of aesthetic production lies an exercise of translation, from personal impressions to interpersonal expressions or from visceral affects to intelligible utterances. Salmona transposes the sensation of living in Bogotá — protected by mountains and lulled by thin air — into three-dimensional dwellings with stepped profiles, curved bodies, and angular corners.

And what about cinema? How does a two-dimensional medium enact this transmedial mediation from sensation to an image? In Memoria, Apichatpong Weerasethakul brings Bogotá to the silver screen using a method not unlike Salmona’s. The director composes complex shots with considerable depths of field: in the background, he places mountains, stairs, and other ascending structures that engulf the characters in the foreground, as if they are in the belly of an animal. He follows the traditional rules of perspective used in painting and filmic images, but the vanishing point climbs upward as it goes deeper into the frame. For example, when Jessica and her brother-in-law Juan are signing a mysterious death certificate and debating the poetic merits of her broken Spanish, there are stairs and mountains in the background. When Jessica sees a man jumping to take cover from the sound of a bus on the Carrera Séptima, there is a brick building with a set of stairs behind her.

Similar looming, magnificent structures occupy the backgrounds of the restaurant scene, the doctor scene, the tunnel scene, and, most notably, the scene in Torres del Parque. Hernan and Jessica sit on a ledge in one of the complex’s many brick pathways; behind them is a monument, a few trees, and a set of stairs, all of which rise toward the Eastern Hills that embrace the actors. Hernan plays Jessica the sound he has created — which, finally, sounds just like her sound — along with a musical recording where he has mixed the sound with a melody he composed. “I am touched by your interpretation,” she says. Her sound continues to travel across subjectivities and artistic domains.

The significance of this translation lies not in the final product but in the act itself, crucial to social and aesthetic communication but so often fraught. Hernán, the only person who understood Jessica’s sound, disappears into the ether halfway through the film, and we are left to wonder if he even existed. In its second half, Memoria leaves Bogotá for the Eje Cafetero region, the epicenter of Colombia’s coffee production, where Jessica meets another mysterious man called Hernán (Elkin Diaz). Like Funes the Memorious in Jorge Luis Borges’s story, this older Hernán never leaves his village out of fear of overwhelming his infallible memory. He repeats the same few tasks every day, avoiding novel experiences, disjointed from the tyrannical passage of time but protected in an eternal present. When we first meet the new Hernán, Weerasethakul frames him familiarly: his body in the foreground, the imposing, verdant Andes in the back. Spectral memories haunt Hernan and Jessica, and, while they struggle to translate their experiences to others, they do not fall into catatonic solipsism. In fact, Hernán’s fraught relationship with time makes him preternaturally attuned to his space: he scales a fish with virtuosic intuition; he keeps his ears perked for the sounds of nature. When memories become too overwhelming, Hernán and Jessica focus on their immediate present to live in embodied communion with the world.

Memoria dwells on the pleasures and challenges of relaying our personal experiences amid feelings of isolation. The film's incorporation of Salmona’s work as set pieces helps elucidate one of its conceptual gestures: just as sounds cannot be easily put into words, one’s pain cannot be easily rendered to others. Indeed, Salmona captures and communicates a general experience of living in Bogotá, but, as the scene with the man jumping to take cover reminds us, the universality of this truth is not to be taken for granted. Every noise, every sight, and every sound elicits a different experience of spatiality filtered through our own memories. And in a country with such a tumultuous history, it is safe to assume that every person will have a very different relationship with their surroundings.

Still, there is a glimmer of hope. Through cinematography, set design, and sound, Weerasethakul revels in the difficulties of this translation. It is not easy, making it even more enticing, and in this film, the Thai director shows his deftness at converting natural and architectural forms into cinematic images. Jessica’s struggle speaks to the challenges of intersubjective legibility, but Memoria’s perplexing ending urges audiences to sit in the theater and contemplate the mysticism within mundane phenomena. Weerasethakul asks us to wander around and wonder at the world in front of us, to lose ourselves in our reality, magical and supernatural in its way.

Memoria captures the spatial configurations of a city that has lived in the throes of violent memories for too long. The film shows how the screams, cries, and laughter of Bogotá’s denizens echo through the city. Suppose you are born inside the belly of an animal: you might not notice that because it is your home. This is perhaps why Weerasethakul, Jessica, and Salmona have a supernatural talent for recreating the sensation of being in the city. Like Jessica in the music studio, Weerasethakul pauses and plays with language to turn his exploding head syndrome into an external manifestation, one intelligible to audiences worldwide. The director cements his status as a master of contemplative cinema and furthers his mission of exploring the meditative and ritualistic capacities of the medium. We ask language to help us describe sensations and impressions so we can transform them into art, but the question remains what happens when words fail us. Memoria suggests that in such cases, one should sit back, listen to the world’s faintest vibration, and contemplate reality beyond its signification.

¤

LARB Contributor

Juan Camilo Velásquez is a writer and PhD student in cinema studies at New York University. His writing has appeared in Cultural Politics, Film-Philosophy, The Puritan literary magazine, and others.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Aesthetic Weather: On Cole Swensen’s “Art in Time”

John James considers “Art in Time” by Cole Swensen.

The Narrative Wars: A Conversation with Juan Gabriel Vásquez

A major Colombian author discusses the challenges of speaking truth in a “post-truth” era.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!