Spooky Sexy: A Conversation with K. Patrick

Naomi Pearce talks with K. Patrick about their debut novel, “Mrs. S.”

By Naomi PearceSeptember 8, 2023

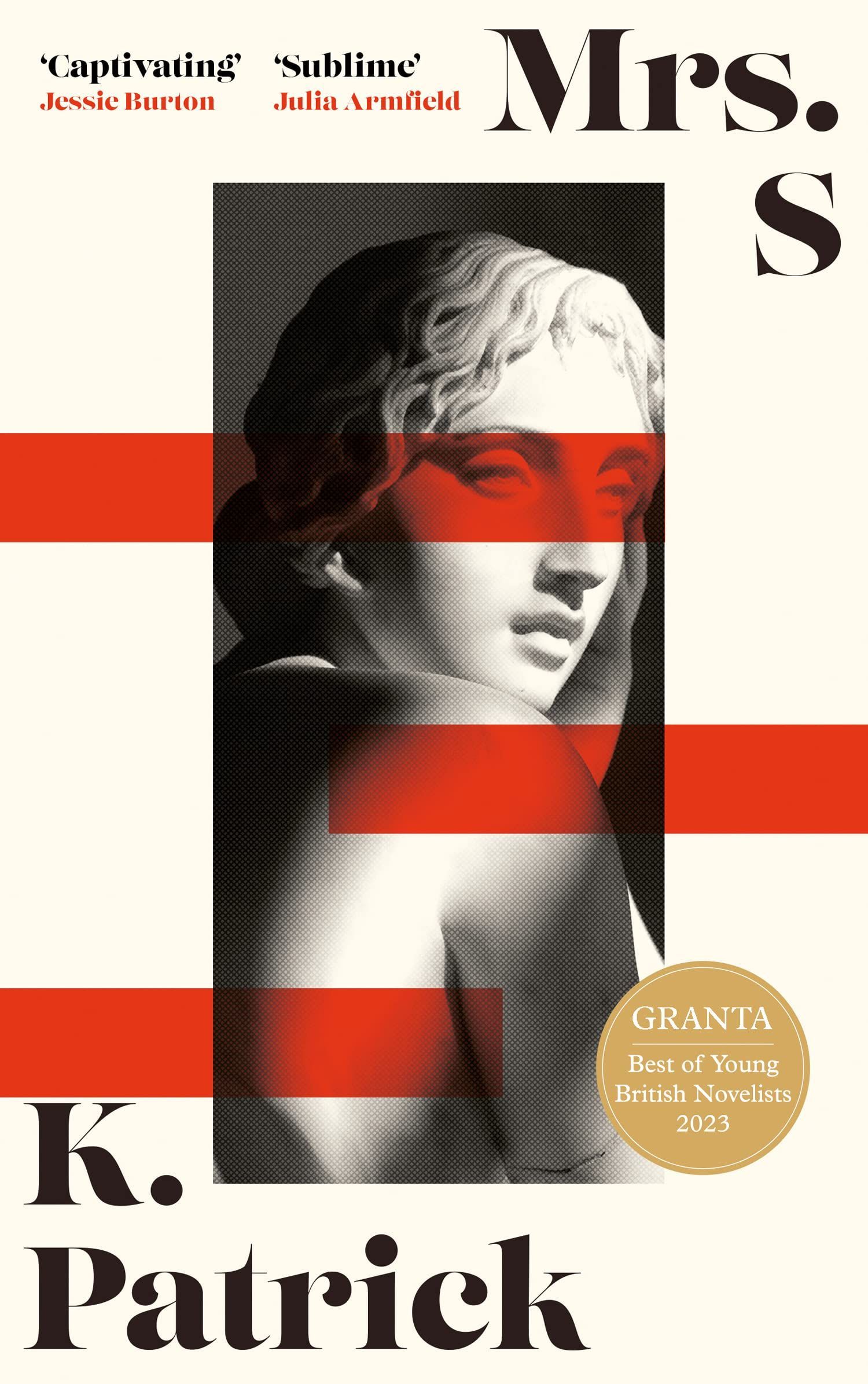

Mrs. S by K. Patrick. Fourth Estate . 304 pages.

AT THE HEIGHT of the pandemic, K. Patrick and I, along with artist Charlie Prodger and art historian Laura Guy, started a monthly writing group named after Rita Mae Brown’s cat “Baby Jesus.” As the days in Glasgow grew darker and shorter, another lockdown imminent, the four of us met at kitchen tables, on park benches, and then over Zoom. We shared our works in progress, argued about structure and tense. With the future unimaginable, we talked a lot about the past.

During this time, K. began writing their horny debut novel, Mrs. S, and I finished Innominate, an arts administration murder mystery. Three years on, as our books make their way into the world and we move unrestricted once again—struggling in fact to remember what quarantine bubbles even felt like—I wrote to K. over email about Mrs. S, the queer possibilities of genre, and the power of reading relationships.

¤

NAOMI PEARCE: In her introduction to the anthology Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2019, Carmen Maria Machado bemoans the tired yet ongoing category-enforcing between literary and genre fiction. Citing author Kelly Link, she turns instead to affect, describing genre as “the promise of pleasure.” I felt this keenly while reading Mrs. S. The boarding school is a well-established context for lesbian melodrama, and the novel seems to embrace its references freely, allowing them to circulate and riff off one another. Can you talk about some of your influences? In what ways do you think genre fiction takes particular pleasure in this proximity to its own past?

K. PATRICK: I love that quote. What could be better than “the promise of pleasure”? To choose a book in anticipation of a specific feeling?

I read Thérèse and Isabelle by Violette Leduc and also her autobiography, Lâ Batarde, which has the boarding school early on. Leduc is one of the only writers who can inhabit a past desire with absolute precision, while also offering the pained retrospect alongside. It’s so accurate, to me anyway, in representing the effect “loving” has on the body. I mean the physical effect—the sweating, the throatiness, the headaches. I think the boarding school, in this context, becomes an ideal space within an unideal institution. You can create a “perfect” privacy between two characters, a walled-in intimacy, pushed closer by an essentially doomed setting. (I spent a lot of time with Fleur Jaeggy’s Sweet Days of Discipline, which does this so well.)

Choosing to write a book that kind of cavorts in genre is (as Nell Stevens recently said to me at an event) like giving a gift to yourself as a writer. You experience your very own “promise of pleasure.” I began Mrs. S with only gratification in mind! Ha.

I think a lot about fantasy too, a twisting of it—this novel was born out of the pleasures I designed for myself when I was a closeted teen, fantasies that I could safely live inside. (Don’t all queers imagine fucking a teacher—or, even better, a headmaster’s wife?!) It’s very beautiful to me that they’ve now been cemented in a goddamn novel, the ultimate mutable reality.

All of which isn’t to say that pleasure doesn’t also involve shame and humiliation—it isn’t pure. Maybe at the apex of the romance genre a kind of purity is attempted. Yes, in order for the romance to function, it has to be thwarted at some point, a fun and dramatic plot twist, but otherwise, the narrative is shielded from bodily complications. Therein lies the romance writer’s ability to promise pleasure to the reader, I guess. I don’t hate that.

It’s interesting that you mention purity and shame because I wanted to ask about the ways in which water is figured in the novel. It feels like a fundamental force, not just actual wetness (hot), but a threat, a state of being. I’m thinking now also about its cleansing properties, both physically and spiritually. Key scenes in the novel feature water, from the swimming spot where our protagonist and Mrs. S escape, to the storm that breaks when they first fuck. I made a note of these lines: “If I could choose a different chest I would choose this water. If I could choose a different body I would choose this water.” Also: “She puts her lips a moment away from mine. I turn to water. Fast as the river.” And finally, after Mrs. S leaves our protagonist’s bedroom for the last time: “I am made from weather.” Can you talk about water as a symbol or metaphor in the book and how it relates to gender and genre?

A friend of mine (thank you, Elsa) once announced, with total authority, that the sea is lesbian. As she said it, I experienced it as a total, undeniable fact. It is a gorgeous feeling! Different, I think, to the notion of “queering,” in which something becomes queer. I find it too historical, like the thing wasn’t queer to begin with, which it definitely was, ha. There are plenty of things that we just gut-know are gay. I love this insider information. I began making up a word to try and capture that experience—this knowledge that some matter is just queer, and only got as far as merging queer and eerie (courtesy of Mark Fisher) to make queerie (hello PhD that never happened). I wanted to try and reflect that instinct. To know, in your stomach, in your fingertips, that something is queer. Reinvent the idea of “fact.” It gets close to what José Esteban Muñoz says in Cruising Utopia—that in approaching any kind of queer history, traditional ideas of evidence won’t work. It’s the ephemera that matters. Can that be captured in text? Should that be captured in text? It both bothers me and excites me.

You can find the reasons why. Water is very personal, isn’t it? Or, at least, we make it personal. In its sweeping indifference to the body, it has potential, possibility. It offers different movement, different time. Creaturely too. In quite a literal sense, it’s a site of ongoing transformation. There’s an unknowability that I think is what echoes in my trans body, anyway. There’s no end, no finish, right? That’s the dream. I guess that’s where the idea of being “made from weather” comes from too. To be fucking unpredictable! To be fucking unexplainable!

Right. Uncontainable too. I like that. It reminds me of Voice of the Fish by Lars Horn—do you know it? In the opening essay, they write: “I regularly find myself trying to explain my gender in terms that will make it intelligible to another.” Elsewhere, they have talked about embodied sight: “Looking is textured. It comes with taste, smell, tactility.” Your observations in Mrs. S are excellent, so forensic yet poetic. I love the short sentences and heavy description. This insistence on a gaze that still manages to incorporate all the senses while destabilizing the primacy of sight feels particularly queer. What do you think?

This weighed so heavy on my mind while I was writing Mrs. S, but I’d not been able to articulate it. Romance is all about looking, isn’t it? I figured the book would be simple: my goal was to have this narrative alive with gay sex. But it wasn’t simple at all, I think, because the “looking,” the legacy of it in text, wouldn’t work for me. I had to come up with a style (which has really polarized readers and reviewers in a way I didn’t expect). It was reverse engineered. The first thing I did [was write] the sex scenes. I rehearsed this writing, had to get the gaze to emerge. The style, the tone, even the plot of the whole book was born from that. This very immediate present tense was what I ended up with. It was tough; it meant this intense distillation of time, almost a second-by-second surveillance. Barely a heartbeat could go unnoticed. But that is queer, I guess. You never stop reading the room hardcore. Am I safe, who can I fuck, what is like me, and everything in between.

I’m interested in this process of reverse engineering and how it relates to genre. It’s particularly true of crime fiction, where the reader must reconstruct a scene or re-enliven a body. Like you, when I was writing Innominate, which is a mystery novel, I worked backwards.

You mention surveillance—this gives the gaze a violence. Throughout Mrs. S, desire is threaded through with pain: rose thorn cuts; wasp stings; the malevolent, homogeneous “Girls.” I kept thinking about the pandemic writing group and our concept (is that the right word?!) of “Spooky Sexy.” Mrs. S feels very Spooky Sexy! In my notes from that time, I wrote Spooky Sexy: being wet around death. Access and denial seem crucial characteristics of Spooky Sexy, as does power. I remember Charlie talking about Jane Campion’s film Power of the Dog (2021), the scene where the young guy takes the cigarette from the older guy’s lips and has a drag while looking at him with big domme energy. This moment shifts the narrative without language; there’s something Spooky Sexy about the viewer witnessing this power shift. What does Spooky Sexy mean to you?

Spooky Sexy! Bear with me while I think this through … Now realizing how close that runs to a queer eerie too, ha. Spooky sexy, there’s so much in it, isn’t there? It’s even in the atmosphere when you’re talking about a hot queer book. And hot is, at its finest, deeply immoral. Maybe it’s tension. Like a horny haunting. All these different selves, all these pieces of queer information you bring to any encounter. When you’re constantly reading the room hardcore—I guess it’s a “hardcore noticing”: there’s an inevitable tension. You’re wide open to even the smallest shift. And you’re right, in that there’s a ranking, a measuring-up.

There’s also no accounting for context, in a way. The boarding school is a great space for this to play out. I was interested in the idea of a collective desire, of The Girls like a Greek chorus, a unified gaze that’s almost all-knowing, and in that knowledge creates violence. That’s Spooky Sexy? There’s a grinding between The Girls’ gaze and the protagonist’s gaze, I think. I hope.

Maybe now is the time we talk about Patricia Highsmith? Mystery and romance genres meet! In her how-to writing guide Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction (1983), Highsmith argues that “a suspense story is one in which the possibility of violent action, even death, is close all the time.” The same could be said for Mrs. S. What do you think about the shared language of mystery and romance?

Ooooh. Again, I think it’s about tension? I mean, the two great themes of life, at least when it comes to the novel, are sex and death? Cheesy to type, but undeniable. They motivate each other in very nonlinear ways. Apologies for writing nonlinear. That sex/death relationship gets even murkier when it comes to queerness. It can be a tightrope. Thinking now, I wonder if they aren’t similar, mystery and romance, because they are also both places where language can fail so spectacularly. For me, faced with writing a kind of romance, the issue I had was that desire is already a perfect fiction, in and of itself. How much can ever be uncovered? How much can ever be replicated? Maybe the same thing happens with mystery. It’s in the name, I guess. This quite literal rendering of text’s shortcomings, the limit you bump up against. You persevere, go after the unsaid, and then what? I love the burn of a good mystery, the cheapness of the satisfaction you feel in the reveal, because what you really need answering cannot possibly be answered.

Absolutely. The burn. Like that feeling when you realize a crush isn’t reciprocated. You kick yourself: How could I have got it so wrong?! This notion of projection also feels important to romance and mystery. It makes me think, too, of the role of creativity in the novel—the references to the unnamed dead author, to poet Federico García Lorca and painter Georgia O’Keeffe—and how this relates to desire. Desire as something that needs to be constructed, like an artwork. What is being constructed when we desire?

Oh no, I can feel what I’m going to say … The self?! The self is constructed? Do I actually believe that? I’m not sure. Maybe. It is built, but in the novel, it’s for the satisfaction of pace. I wanted the desirous body to come through as well. We sever from ourselves, don’t we? When we’re mid-desiring? There’s mimicry, projection, all of Whitman’s multitudes. We experiment, burn out, convert all sorts of ordinary measurements into the extraordinary, seconds become as long as years … See, there’s a deep cliché too. I love the clichés, the fucking yearning; the vortex has remained the same. And art won’t ever stop sticking a finger in it. Because it’s fun.

Speaking of clichés, of inhabiting them to break them open, I love the Housemistress character and her friendship with the protagonist. Their relationship of queer kinship feels like the real romance of the novel. But there’s also a sadness—how quickly they dismiss each other: “[Y]ou’re hardly my type.” Their longing, at least in the case of the protagonist, attaching to unavailable, arguably harmful Mrs. S—which reminded me of Lauren Berlant’s writing: “[W]here love and desire are concerned, there are no adequate examples; and all of our objects must bear the burden of exemplifying and failing what drives our attachment to them.” To me, it felt like Mrs. S was an exorcizing of heterosexuality, that in some ways, by setting this narrative in the 1990s, there was a desire to relegate the dynamic between Mrs. S and our protagonist to the past.

I read so much Berlant while thinking Mrs. S through and I love that quote.

The Housemistress. She was the big surprise in the text, the thing that I, as the writer, really needed. It’s interesting that you read a sadness. For me, their relationship is very romantic, if not more romantic, than the protagonist’s relationship with Mrs. S. I guess, though, because it’s romantic it comes with an in-built sadness. They do long for each other. And you’re right—it’s a cross-time longing. They want each other before this book and they want each other in the future, way after this book. That was important to me. To have butch everywhere.

Although, maybe it’s important to say, I don’t read their lack of traditional coupling as a failure?

An exorcizing of heterosexuality! Let’s do it. You know, it wasn’t part of my conscious thinking at the time of writing, but it makes me feel very nice that you’d believe I’d be so smart. The book’s ending is maybe what we should talk about, then? This is the moment of exorcism, isn’t it? A turn towards the queer self, desire-constructed or otherwise. What I did want, very consciously, was a sense of futurity, which also ties into the Housemistress, I suppose. An understanding that the protagonist would carry on without the book, and the reader might be left fantasizing about them, their body, their feelings, the day after, or the month after, or the year after, the last scene. These endless transformations they’d undergo, I guess. Whereas Mrs. S, the character, is left behind. She’s tethered to the object, to the book—she’s the title, you know! That’s it. That’s the entirety.

¤

K. Patrick is a writer based on the Isle of Lewis, Scotland. In 2021, they were short-listed for The White Review’s Poet’s Prize and Short Story Prize, and in 2020 were runner-up in the Ivan Juritz Prize and the Laura Kinsella Fellowship. They were selected as one of The Observer’s 10 best debut novelists for 2023 and Granta magazine’s “Best of Young British Novelists.” Their debut novel, Mrs. S, was published by Fourth Estate (UK) and Europa (US) in June 2023.

Naomi Pearce is a writer living in West Wales, whose debut novel, Innominate, was published by MOIST in July 2023. Current projects include Good Bad Books? (featuring K. Patrick) at the Barbican, London.

LARB Contributor

Naomi Pearce is a writer living in West Wales. Her essays and fiction have been published by Art Monthly, e-flux Criticism, Kunstverein München, MIT Press, and The White Review, amongst others. Her debut novel, Innominate, was published by MOIST in July 2023. Current projects include Good Bad Books? (featuring K. Patrick), a workshop and event series exploring the imaginative spaces of genre fiction held at the Barbican, London.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Is This Desire?: On Jane Campion’s Anguished New Epic, “The Power of the Dog”

Ryan Coleman considers the anguished, queer theology behind Jane Campion’s “The Power of the Dog.”

Semi-Plausible Histories: On Torrey Peters’s “Detransition, Baby”

A sparkling debut novel challenges ideologically charged notions of gender and motherhood.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!