Spooky Entanglements: “Anatomy of a Fall,” “Constellation,” and “The Signal”

Michael Szalay on twinned productions and other IP shenanigans in “Anatomy of a Fall,” “Constellation,” and “The Signal.”

By Michael SzalayMay 25, 2024

ONE DAY BEFORE the 2024 Oscars, Variety reported that screenwriter Simon Stephenson had alleged The Holdovers, then up for Best Original Screenplay, was “plagiarised line-by-line” from one of his scripts. But “brazen” similarities notwithstanding, Stephenson took his “credit dispute” to the Writers Guild of America, rather than a case to court, presumably because copyright infringement is difficult to prove. The law enforces ownership not of ideas themselves but of their expression in concrete language and specific scenes, and it has been notoriously hard for plaintiffs to establish sufficiently substantial similarities of expression. Ideas are cheap commodities in Hollywood—when they are paid for at all.

Consider the longstanding phenomenon of “twin films”—two movies released more or less simultaneously treating the same topic or adapting the same text. Two Ivanhoe films premiered in 1913, two The Three Musketeers in 1921. Recent twins include Volcano and Dante’s Peak (1997), Deep Impact and Armageddon (1998), Olympus Has Fallen and White House Down (2013), and A Quiet Place (2018) and The Silence (2019). The mechanisms of replication are likely various. A script is leaked, or a pitch is made to two companies, only one of which wants actually to pay for it. A studio keeps tabs on and copies a rival from afar. Apple gets wind that Netflix is developing a European co-production in which an astronaut leaves behind her loving husband and young daughter to conduct experiments on the International Space Station (ISS). The mom never makes it back to her family, whose plight allegorizes the failed promise of interstate—especially intra-European—cooperation. Apple loves the idea and decides it wants one too. Or maybe Netflix gets wind that Apple is developing such a show and decides it wants one too.

Now they both have one. Both released earlier this year, Constellation (Apple TV+) and The Signal (Netflix) are astonishingly similar. Amir Hamz, a producer on The Signal, told me he has been trying to figure out how that happened since learning about Constellation. His show had been in development since 2017. “I can only assume,” he said, “that somewhere, somehow, somebody must have gotten a hand on the script.” He thought the German Motion Picture Fund, which funded both shows, might have shared it. “The sheer fact that there are so many similarities” dismayed him. But “we can’t prove it,” he added, and so he was left in “the field of conspiracy.”

Peter Harness, Constellation’s creator and showrunner, was more philosophical. “It’s as much a surprise to me as anybody,” he said, when I told him of my conversation with Hamz. There are often “weird synchronicities” between productions that come out at the same time, he added, citing The Sopranos (1999–2007) and Analyze This (1999). “It’s a bit strange,” he conceded, but after “trying to sell original ideas for many years, you know the same kind of ideas do weirdly tend to emerge.” Having said that, and having cited differences in “the specifics and tone” of the two shows, he added, “I think there’s a universe in which both series can live.”

With his references to “weird synchronicities” and alternative universes, Harness evokes the “spooky action at a distance” that Einstein attributed to quantum-mechanical accounts of “entangled” particles mirroring each other faster than the speed of light. Constellation relishes such spooky action; invoking quantum entanglement, it doubles its universe and characters to eerie effect. The Signal performs a related doubling, and perhaps there is a universe in which one or the other inoculates itself against future accusations of theft by treating replication as a cosmic inevitability. Occam’s razor still points to significant … borrowing, let’s agree to call it.

But there are other synchronicities at work—synchronicities regarding labor and gender that derive not from the quantum realm but from domestic life, and from deep anxieties about the maternal bonds that working women can and cannot sustain. Anatomy of a Fall (2023), winner of the 2023 Palme d’Or and the 2024 Oscar for Best Original Screenplay, explores that anxiety in ways those space melodramas simply do not. Whether Anatomy’s fascination with the gendered division of labor fully accounts for its weird affinities with these two TV melodramas is unclear. Warning: Spooky action ahead.

Space doubles. From Constellation, Apple TV+.

An adroit, relentlessly intelligent courtroom drama, Anatomy is by far the most accomplished of the three. And few would mistake the art-house hit for a slightly varied version of the streaming space melodramas (which followed it to market by roughly eight months, in any event). The film might thus be said to justify the law’s restrictive approach to copyright: execution is everything, and proves, if nothing else, that two productions can share broadly similar plot points and still be meaningfully, fundamentally distinct. But let’s note the similarities nevertheless.

All three place on trial an ambitious woman who has risen seemingly too high. And though with different emphases, all three describe a punitive “fall” that returns these women to earth (two meet their deaths, and one faces withering public scrutiny). In Anatomy, the trial is literal: German citizen Sandra Voyter (Sandra Hüller), a renowned writer of autofiction, is accused of murdering her French husband, who either fell or was pushed from the attic window of their mountain fastness (“I didn’t realize it was so high,” says Sandra’s lawyer upon visiting the home). We do not learn definitively if she is guilty or innocent. But Sandra is also accused, more fundamentally, of being an unapologetically strong woman who has placed work before family.

Sandra Voyter at the height of success. From Anatomy of a Fall, Les Films Pelléas/Les Films de Pierre.

The husbands in The Signal and Constellation are both schoolteachers and, like the husband in Anatomy, their child’s primary caregiver. In Anatomy and Constellation, the men wag fingers at their wives and accuse them of neglecting their children. In Anatomy and The Signal, the child is physically impaired, and in all three, the child has lost a parent and must make peace with that loss and the fact that mom’s ambition seems indirectly to have caused it. In Constellation as in Anatomy, the child tells a lie on mom’s behalf at a crucial moment. A few more plot points to suggest that somewhere, somehow, a script was circulated: In all three, the child is either offered or believes it possesses what Anatomy calls a “medium” with which to speak to its dead parent; in all three, the discovery of secret audio recordings casts the mother’s actions in a new light. In The Signal, a character reassures another that she’s not crazy, despite seeing things that aren’t there; “the thing about people with visions,” a friend remarks, is that “some end up in prison, some end up with the Nobel Prize.” Constellation sports a Nobel Prize–winning physicist who ends up in prison. Weird synchronicities indeed.

More interestingly, each of these three stories turns on an inverted division of labor. In Anatomy, during a vitriolic dispute that ends in off-camera violence, Sandra’s husband complains about “how things are divided between us.” Their household responsibilities are “out of balance,” he spits. Constellation’s pilot evokes that line in a garbled recording of a Russian cosmonaut: “The world is the wrong way around.” Quantum physics will eventually explain why the world feels turned on its head, but the simpler explanation is more telling: women away at work leave a household “the wrong way around.”

In Anatomy and Constellation, husbands suffer their wives’ cheating almost as an expression of that imbalance. But the film and show differ crucially in their treatment of infidelity. Jo’s (Noomi Rapace) husband is more civil about her cheating than Sandra’s—no punching the wall, just hangdog pouting. And yet, Constellation uses Jo’s infidelity to divide her into morally good and bad selves, while Anatomy pointedly refuses any such division. Whether morally or sexually, Sandra is two things at once and, as such, a protean Rorschach test for the audience.

Anatomy estranges tirelessly; from one jarring reversal to the next, it supplies son Daniel (Milo Machado-Graner) and the audience with new vantage points from which to reinterpret what moments before had seemed self-evident. We endure a series of testimonials that make Sandra’s guilt alternately incontrovertible and inconceivable. The evidence is overwhelming, until Sandra rebuts it with a riveting, charismatic conviction. Is this rank deception, a star-turn courtroom performance, or absolute authenticity? Like Daniel, we are asked to judge. “[A]ll we can do is decide,” Daniel’s guardian tells him. “Since you need to believe one thing but have two choices, you must choose.” The choice couldn’t be starker, but it’s not just between Mom’s innocence and guilt. His vision only half-impaired, he is neither fully clear-eyed nor fully just—appropriately so, because he must decide not simply what happened but which version of his mother he wants.

¤

Prior to Daniel’s choice, Sandra exists in an everyday version of what Constellation calls “a quantum superposition.” “There’s a world in which that particle is black and a world in which that particle is white,” a physicist explains to Jo’s daughter. “And there’s a kind of point of liminal space between those worlds, where the particle is black and white at the same time. And they don’t seem to want to decide which state they’ll be until someone looks at them.” Invoking the quantum-mechanical “observer effect,” in which observing the indeterminate particle in question precipitates one or another definite state, the show appears to leave us where Anatomy does. These particles “don’t seem to want to decide,” so we, as Daniel’s guardian puts it, “must choose” for them.

Anatomy takes that choice seriously in ways the streaming shows don’t. Constellation produces “black” and “white” moral registers: faithful Jo is good and cheating Jo is not—indeed, she appears in the season’s last shot as an undead space ghoul. Those front-loaded registers rob the observer effect of its force: we’re not really asked to decide which version of Jo we want. Anatomy implicates us more uncomfortably—and counterintuitively so, insofar as Sandra’s potential crime is far greater than Jo’s. In important ways, Sandra is both innocent and guilty, until Daniel and the audience decide one way or the other. And that indeterminacy has affective purchase precisely because it derives from an everyday rather than a science fictional impasse.

Sandra evokes the leads of fellow 2023 Best Picture nominees Past Lives and Barbie, both of whom walk a knife’s edge, teetering between two versions of themselves. And, indeed, she evokes the science at the heart of Oppenheimer, a film that is fascinated by the observer effect. But in Anatomy, no quantum-mechanical gee-whizzery distracts from a more mundane thought experiment: what if parents, and mothers especially, could be both murderously selfish and loving caregivers? What if they could be forever at work and at the same time forever with their families? What if they could live only for themselves and their careers while also sacrificing everything for their children? Anatomy’s triumph is the uncertainty it generates around these questions. Can’t we have two things at once? Can’t Sandra have it all?

The answer, for Sandra’s husband at least, is an emphatic no. He thinks of their co-parenting as her theft of his labor—and his intellectual property too. Having complained vehemently about their parceling-up of work, he accuses her of “plundering” his book idea, about a man who wonders how his life would have been without the accident that killed his brother. One day he wakes to find himself in two different realities, one in which the accident is the central event in his life and one in which the accident never happened. The husband does not finish that story, he claims, because of the burdens placed upon him as a caregiver. Sandra, meanwhile, does nothing but (her own) work, however exhausted she may feel. “I can work in any environment, any condition,” she brags. She runs with his premise, allegedly with his permission, and writes “over 300 pages,” not about a man and his brother but about a woman and her daughter. Sandra names her novel Eclipse, a title that neatly metaphorizes her fortunes relative to his.

Now let’s imagine one or even two hungry writers who, taken with that book’s idea, decide to approach its title literally. Why not set Eclipse … in space? Like Sandra’s novel, The Signal and Constellation lengthily elaborate a condensed premise, only this time the stories are about a mother and her daughter as they confront the uncanny doubling of their lives. And now, the gimmick takes over. We still see the outlines of Anatomy’s domestic allegory, but obscurely.

¤

That might be uncharitable. Constellation intelligently riffs on the “second lives” that have defined two-plus decades of prestige TV. The science fiction does smartly allegorize select features of family life; its doubling consciously speaks, for example, to the felt absenteeism of parents who don’t go to space but who nevertheless work all the time. “Maybe some people can be there and not there,” one bereft child muses to another.

Equally, the show resonantly captures the uneasy peace parents and children make with themselves and each other when they realize that their child or parent is something other or maybe even less than they need. In a poignant scene, Jo (in the wrong universe) and Alice (daughter of Jo’s dead double, played by twins Davina and Rosie Coleman) reconcile themselves to each other. “We both lost someone, but we found someone too,” says Alice, before adding, “I need a mummy.” Jo responds, “I need an Alice.” A plaintive response: “That’s me! Mummy, that can be me!” Constellation is family melodrama, after all.

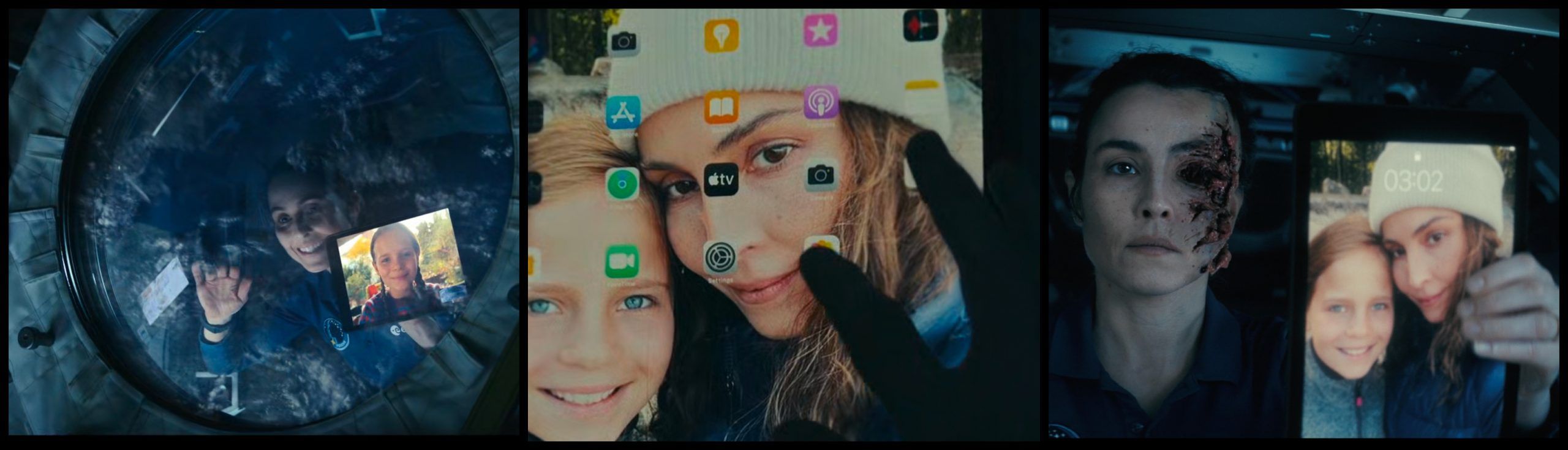

But these potted allegories, one feels, exist in the service of—are entangled with—extraneous ends. For all its considerable uncanny disquiet, Constellation is interested less in the unequal labor required to sustain family life than in the devices that ostensibly mitigate that inequality—like the iPad. Floating in the heavens before the disaster that kills one version of herself and returns the other to the wrong family, Jo looks down on Earth with Alice, who sees what she sees via an iPad pressed against the station window. Later, her finger hovering meaningfully over the Apple TV+ icon, Jo uses the iPad to look at pictures of Alice. In the season’s last shot, meanwhile, an undead Jo holds an iPad and looks pissed, perhaps because she cannot unlock it.

Apple in space. From Constellation.

The iPads are only symptoms of a deeper entanglement, the relative freedom from which marks Anatomy as an “independent” film. Take, for example, how all three productions link their marital and political unions. In Anatomy, the family’s language use evokes EU fault lines. “I’m not French, you’re not German, so we create a middle ground.” Sandra tells her husband. “So nobody has to meet the other on their turf. This is what English is for, it’s a meeting point.” The ISS is another version of that meeting point—or “no-man’s land”—for the international crews on The Signal and Constellation. As such, the station is a metaphor for interstate cooperation, and indeed, the space melodramas use both the ISS and their subject families to allegorize the EU’s promises and failures.

Of the three stories, The Signal is the most invested in the European Union and the least interested in marital labor. The husband is neither bitter nor accusatory. His wife Paula (Peri Baumeister), the lead astronaut, picks up a deep-space voice that sounds like her daughter’s. She concludes that aliens are approaching Earth and is killed because of that theory; the daughter subsequently thinks she talks to her dead mom on a radio. Aliens are not, in fact, approaching; the voice has been broadcast from the original Voyager, coming home. The once familiar but now estranged returns. But despite the fact that Paula works for a female billionaire who loans money only to women, the allegory is primarily geopolitical: the Voyager is a Cold War artifact whose return demonstrates how far Europe still is from unity, and how far it has traveled from what Paula calls, simply, “enlightenment.”

It was perhaps a genuine belief in enlightenment that led Amir Hamz to believe that the Constellation team would share access to the model ISS it was constructing in a Berlin studio. Hamz wouldn’t know how similar the two shows were until they appeared, but he did know during production that Apple was funding a model ISS. He wanted to share costs, and at first his Constellation counterpart seemed interested—until suddenly he wasn’t. “Apple called him off,” Hamz speculated, because it “didn’t want it to be part of a Netflix show.” That should not have been surprising: it’s hardly news in Europe that Apple doesn’t like to share. And it’s worth noting that, for Constellation, the ISS is a metaphor less for interstate cooperation than for the neutral meeting point the streamers pretend to offer—an entertainment kingdom beyond state jurisdiction where global audiences come together in the dark to enjoy shared missions.

“A Netflix show,” The Signal is also invested in that fantasy and in a version of Constellation’s tech boosterism. “[We wanted to] do a collaboration with Google,” Hamz told me, by using a special Google phone in a climactic scene. The deal fell through, but residues remain: “Brave new world,” says a billionaire’s aid, as we cut to a close-up of a giant Android flip phone. The moment is biting, but not simply because the drama believes in enlightenment. The Signal premiered on March 7, one day after the compliance deadline set by the European Union’s Digital Markets Act. After March 6, 2024, globe-straddling leviathans like Apple and Google would be forced to comply with the act’s competition-facilitating provisions. Netflix is the only big streamer not targeted by the act as a “gatekeeper.” The Signal endorses pan-European cooperation while calling out billionaires and hard-right populists. But it does so strategically, we might be forgiven for noting, and in a way that distinguishes it from Apple’s more ostensibly cynical product. That’s one affordance of duplicated IP: it allows a studio, network, or streamer to accentuate an ostensibly telling brand attribute.

In Constellation, European cooperation offers nothing like enlightenment. It’s a hustle, a bogus front for a bad marriage—as to some extent it is in Anatomy. English provides Sandra with a modicum of neutrality, and another way to distinguish Anatomy from the space melodramas is to distinguish their investment in technology from its investment in language—for which there are (at least as of this writing) no available IP rights. But neutrality doesn’t mean cooperation; as Sandra insists, “I don’t believe in the notion of reciprocity.” We’re not sure how to feel about that: is she a sociopath or does she simply refuse the chains with which her passive-aggressive husband would bind her to his failures?

Apple’s melodrama precipitates no equivalent doubt in its refusal of reciprocity. As a physicist tells Jo during the fact-finding hearings that follow her return to Earth, “[T]here are big bureaucracies at play here, Commander. They all have their agendas. […] It’s easy to get ground up in the gears.” The physicist has designed the mysterious gizmo—aptly named the “CAL”—that places Jo in quantum superposition. The fantasy is that those who make the gears won’t be ground up in them: Apple makes world-changing devices; the EU makes regulation. There’s a world in which Peter Harness and Constellation’s nominal creators know they are caught up in those gears, even as they imagine one in which they aren’t. They don’t seem to want to decide … at least not until someone looks at them a certain way.

¤

Featured image: Quantum turtle, National Quantum Coordination Office. Quantum Image Gallery, CC0. Accessed May 21, 2024.

LARB Contributor

Michael Szalay is a film and television editor for the Los Angeles Review of Books. He teaches at UC Irvine and his most recent book is Second Lives: Black-Market Melodramas and the Reinvention of Television (Chicago, 2023).

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Past Is Never Dead: On TV’s Backstory Problem

In the latest Screen Shots column, Elizabeth Alsop explores the ubiquity—and limitations—of the “trauma backstory.”

Such Little Babies: On Tom Perrotta’s “Tracy Flick Can’t Win”

Annie Berke breaks down the appeal of the title character in Tom Perrotta's "Tracy Flick Can't Win."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!