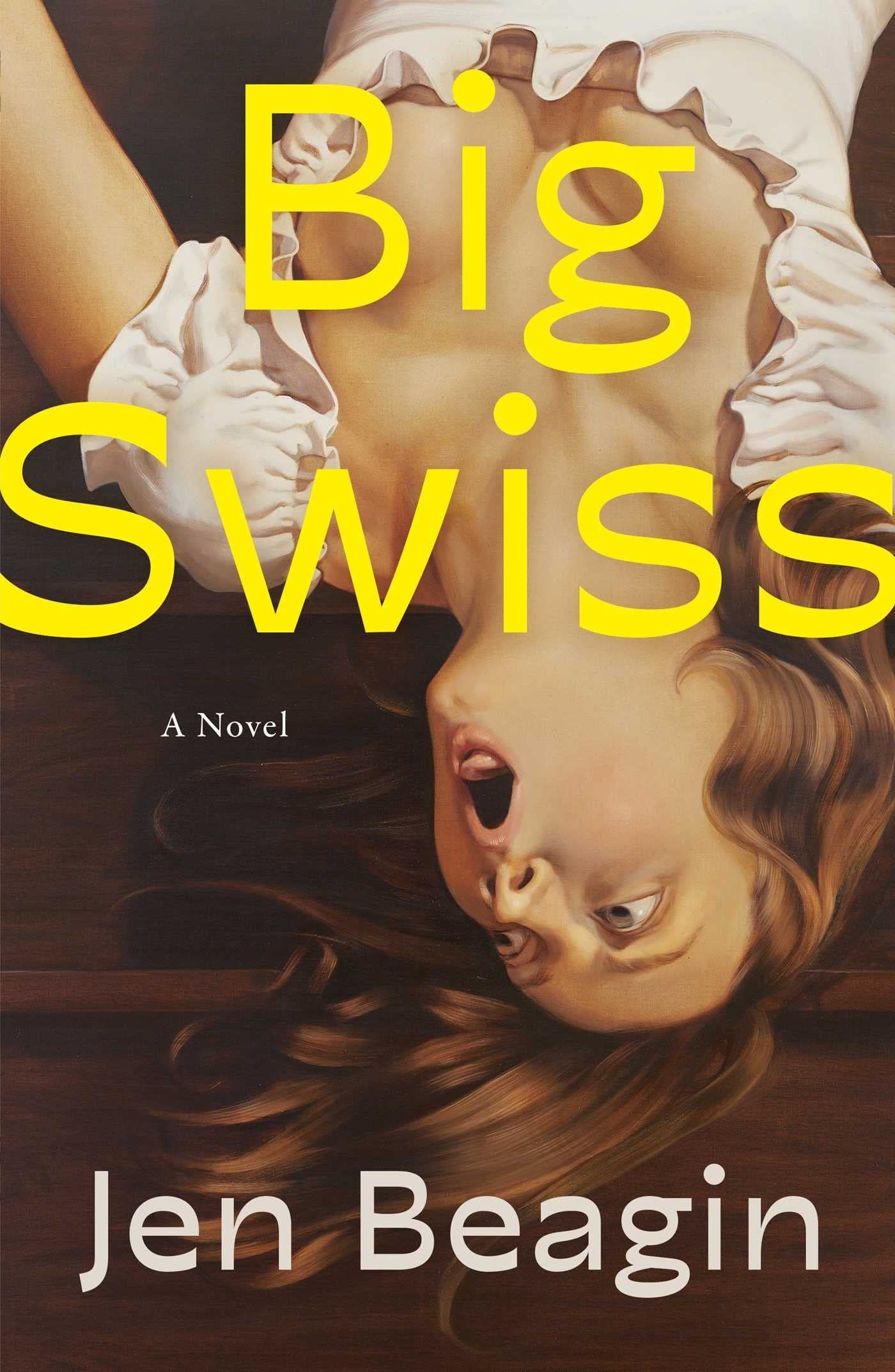

Sexual Transcription: On Jen Beagin’s “Big Swiss”

Madeleine Connors reviews Jen Beagin’s new novel “Big Swiss.”

By Madeleine ConnorsFebruary 21, 2023

Big Swiss by Jen Beagin. Scribner. 336 pages.

WE LIVE IN an era preoccupied with trauma and sex; both have become problems we can’t seem to solve. Every day on Instagram, I encounter pastel-colored infographics encouraging me to enforce boundaries, unpack trauma, expel toxic relationships, and have more fulfilling sex. I’m beckoned to take a quiz to identify my attachment style. My personality is apparently a confluence of gaping childhood wounds. It’s all so clinical and joyless: the romance and spectacle of our lives neatly squared away with diagnoses and prescriptions. Whatever happened to drama, for drama’s sake? Greta, the protagonist of Jen Beagin’s daring and biting new novel, might have the answer. In Big Swiss, trauma and sexual obsession intertwine to create a sprawling and delightful mess.

In the novel’s opening pages, everyone is maimed by trauma but disinterested in self-pity. In fact, the characters stubbornly resist victimhood. “Trauma people are almost as unbearable to me as Trump people. If you try suggesting that they let go of their suffering, their victimhood, they act retraumatized,” says one of the characters — affectionately nicknamed Big Swiss — to her sex therapist, Om. Big Swiss is seeking counsel because, despite being married, she has never experienced an orgasm. She was also the victim of a brutal assault, and the perpetrator is set to be released from prison next month. After revealing this detail, Big Swiss casually advises her new sex therapist, “Also, don’t read into this too much.”

So, what happens when you don’t read too much into your wounds? As it turns out, a lot of unhinged sex and the subsequent therapy needed to interrogate it.

After Big Swiss’s session with Om, Beagin introduces us to Greta, who, having survived a turbulent youth that included her mother’s suicide and her own broken engagement, has found herself in Upstate New York transcribing Om’s sex-therapy sessions for a living. Om, as surmised by Greta, is equal parts horny charlatan and pop psychologist: “Om’s relationship-coaching style seemed reminiscent of getting hit on at a bar. Not by a yoga teacher, as his name would suggest, but by an unneutered therapy animal.”

In their initial meeting, Om says, “Hudson is where the horny go to die.” The novel offers a satirical take on our therapy-obsessed culture, our need to prescribe meaning and labels to every banal event in our lives. Greta is refreshingly skeptical of therapy, or at least considers it an expensive, navel-gazing pastime of bored people. In her own bout with therapy, Greta is “diagnosed […] with emotional detachment disorder, which seemed like a stretch to Greta, who preferred to think of it as ‘poise’ on a bad day, ‘grace’ on a good one, and, when she was feeling full of herself, ‘serenity.’” Greta does not attend therapy sessions but transcribes them, giving her a voyeuristic delight. She becomes privy to people’s emotional interiors without doing the taxing work of keeping up relationships.

At first glance, Greta may seem like a familiar protagonist, especially in recent years when novels like Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018) and Lisa Taddeo’s Three Women (2019) have been particularly interested in female despair. This archetype of a distressed woman has overwhelmed our zeitgeist by emerging as an antidote to the “striving girlboss” figure. Greta loves to sabotage her way through life. Yet, Beagin’s witty and tender rendering of Greta keeps the reader rooting for her, even when Greta begs to be abandoned. The intrigue surrounding Greta is not derived from her tortured past but from the way she moves through the world carrying her torment.

Like everything else in the novel, the town of Hudson, New York, is described with mordant humor. Greta had “heard Hudson described as a college town without a college, or summer camp for adults, but it seemed more like a small community of expats. Everyone behaved as if they’d been banished from their native country.” The world of Hudson is described so amusingly and vividly that it is tempting to want to take up residence, sanctimoniously perusing the dog park with a three-legged rescue. Greta lives in a decaying house with her longtime confidant, the town eccentric, Sabine. Their home — “albeit beautiful nonsense: crumbling plaster walls; layers of peeling wallpaper” — is barely inhabitable and, like the women who dwell in it, too cold for comfort. So much so that “Greta had heard the house described as ‘the Fight Club house with comfy furniture.’”

Greta’s relationship with Sabine — the only relationship that she has sustained over decades — had “[t]he feeling of being driven somewhere while sleeping in the back seat.” Sabine is also single and newly divorced in her mid-fifties. She has a drug habit: she would “snort a line of cocaine or pop a few pills if you put them in front of her but stayed away from hallucinogens.” She’s also hell-bent on getting miniature donkeys for their property, which the reader suspects are a sublimation for romantic connection. When the donkeys finally arrive, Sabine tearfully asserts: “Someone told me mini-donkeys could mend a broken heart.” And yet, in spite of these quirks, Sabine acts as Greta’s confidant, offering her own morsels of wisdom.

For all the discussions of trauma and anxiety, Beagin’s novel is satisfyingly dirty — and perhaps a little deranged. I mean this as a compliment. The characters partake in sexual scenarios that might even make Philip Roth’s protagonists blush. There is an inherent thrill to listening to people describe their sex lives, as Greta does every day for her profession. Written in the style of a transcription, the novel includes intriguing anecdotes of sex told through the perspective of Om’s therapy clients. Childhood proclivities and memories make their way into the bedroom. One client confesses, “I gave her face a little porny slap,” while his partner later contradicts his account. Om’s advice seems anecdotal and too obvious. He asks Big Swiss, “Would you be willing to try masturbating with a vibrator?” Big Swiss offers up that her sexual imagination is awakened during Law and Order: SVU. How does all this fevered sex talk affect Greta? She once jokes: “[I]f you know anyone who transcribes interviews from home, chances are they spend most of the day furiously masturbating.”

Greta becomes preoccupied with Big Swiss and her omissions in sex therapy. Her obsession leads her to listen “to the new session without transcribing it, as if it were a podcast or radio interview. Big Swiss’s voice tumbled out of the speakers and steadied Greta’s nerves as she repaired the windows with Gorilla Tape.” Greta’s voyeuristic interest in Big Swiss begins to feel sentimental, even romantic. When she finally does encounter Big Swiss at a dog park, she is even more beautiful than Greta could have imagined, “her nose bonier, her brows darker, her hair longer, wispier, blonder, nearly platinum.”

Beagin gives us satisfying windows into Greta’s past lives to contextualize the mess she’s found herself in. One of these lives includes a dissolved engagement with a man named Stacy whom she met while working as a waitress. His dialogue is charmingly written in a Boston accent, with lines like, “Was he a bank robbah?” Stacy is unfazed by Greta’s childhood, which included book theft, a rambunctious sexual appetite, and several unorthodox guardians after her mother’s suicide. Stacy and Greta have a few good years together, so much so that Greta “felt distinctly as though she were sleepwalking, or in a perpetual state of daydreaming, and yet they managed to do things like have sex and travel abroad.” But Greta resists this pleasant domesticity and breaks off the engagement to aimlessly wander through her thirties.

However they might posture and pontificate at dog parks and farmer’s markets, the characters cannot escape the horrors of their pasts. While transcribing Om’s therapy sessions, Greta learns about the violent assault Big Swiss has survived at the hands of a man who will soon be released from jail. Big Swiss recounts the event in graphic detail: “I realized that what I was smelling was not the river but my own blood.”

When Greta’s infatuation culminates in the coincidental meeting at the dog park, she can’t help but invite Big Swiss to drinks, disguising just enough details of her life to not draw attention to herself or the fact that she’s intimately aware of Big Swiss’s life. A fiery and passionate affair ensues while Greta tries to conceal her double life as Om’s transcriber. Despite their all-consuming affair, Big Swiss still seems guarded: “Shockingly, despite ample opportunity, Big Swiss had yet to mention being beaten half to death. Not a whisper. Nor had she mentioned, or even hinted at, her attacker’s recent release from prison.” In a moment of speculation before sex, Greta “recalled a recent transcript in which a new client of Om’s had identified as a sex and love addict whose drug of choice was ‘fantasy and intrigue.’”

Yet nothing lasts. The turbulence of the relationship begins to taunt Greta. While carrying out their affair in bars and alleyways, Greta feels a gnawing sense of doom: “It was Greta’s desire that had mutated, she thought on the toilet. She’d become a vile, greedy nightmare, seemingly overnight.” Greta begins to sabotage the relationship with possessiveness. While transcribing Big Swiss’s therapy session, she hears Big Swiss describe her as having “an air of doom about her. She seems profoundly lonely. It’s part of my attraction to her.”

By manipulating Big Swiss, Greta burrows further into her own self-loathing. It reinforces her image of herself as unlovable, selfish, and conniving. For Big Swiss, the affair distracts from the disquietude of her attacker being released from prison. In a tense dinner scene with Big Swiss and her husband, Greta and Big Swiss begin bickering. Her husband observes that they’re like sisters, to which Big Swiss coldly retorts: “We’re more like mother and daughter.”

Big Swiss eventually comes to discover Greta’s true identity, and the affair tapers off, at least for now. Om confronts Greta, to which she replies, “I feel a little relieved, to be honest. […] I couldn’t maintain the charade for much longer. Believe it or not, I usually avoid conflict.” Om offers sessions to Greta as consolation for her scheme. Greta realizes that she “had been quietly crutching around on her own shitty history for over thirty years, and maybe it was time to put down the crutches. Maybe Big Swiss had something to teach her about living.”

In the end, Greta’s answer lies within her own history. She was, in her teenage years,

just beginning to understand that human relationships were pure folly, because nothing was ever perfectly mutual. One person always liked or loved the other person a little more than they were liked or loved, and sometimes it was a lot more, and sometimes the tables turned and you found yourself on the other side, but it was never, ever equal, and that was pretty much the only thing you could count on in life.

This may be true, but through Greta’s eyes, we might understand that this is what makes relationships worthwhile. The sting of attempting to love, failing, and trying again is when life is at its fullest and most vibrant — if only we could get out of our own way.

¤

LARB Contributor

Madeleine Connors is a stand-up comedian and writer living in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in places like The New York Times, Bookforum, and Vanity Fair.

LARB Staff Recommendations

They Toss Bodies at You: On Mariana Enríquez’s “Our Share of Night”

Elizabeth Gonzalez James reviews Mariana Enríquez’s “Our Share of Night.”

I’m Looking to Jump Ship Sooner Than I Should: A Conversation with Percival Everett

Percival Everett, this year’s LARB Lifetime Achievement Award winner, in conversation with Ayize Jama-Everett.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!