Save Yourself: On Shahriar Mandanipour’s “Seasons of Purgatory”

Mandanipour’s characters oscillate between stoicism and struggle, fantasy and certainty.

By Lee ThomasFebruary 17, 2022

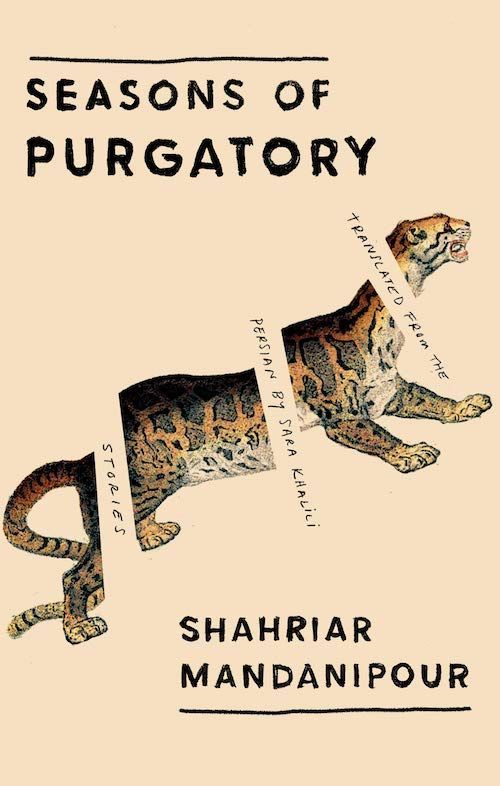

Seasons of Purgatory by Shahriar Mandanipour. Bellevue Literary Press. 208 pages.

HUMAN BEINGS ARE garrulous creatures who make sense of the world through stories. History — who controls it, who imposes it — has sparked wars and purges, censorship and renaissance. The fate of civilizations rests on narratives imposed and erased. Few understand these stakes better than the exile, and Iranian writer Shahriar Mandanipour is no exception. A new collection of his short fiction, Seasons of Purgatory, spans decades of the writer’s career, beginning with his earliest published story, “Shadows of the Cave,” which appeared in Persian in 1985 and English in 2018. Sara Khalili’s excellent translation conveys the dreamlike quality of Mandanipour’s prose: the stories often read like fables or campfire tales, disputed family lore or ghostly myth.

Violence, both manmade and natural, infuses Mandanipour’s work. In “Shatter the Stone Tooth,” a young man stationed with the Development Corps in rural Guraab writes disturbing letters home to his fiancée, who grows dismayed at the bleakness he describes:

Here, everything whirls around in a wind tunnel and turns into dust. The black shadows of the days, the darkness of the night … They gnaw on dry bread; they steal if they can; like dogs, they hide their meager trifles from one another in a hundred little holes; they beat their wives at night and tell one another about it …

The man becomes obsessed with an ancient stone figure carved in a cave wall, while his only friend is a stray dog the townspeople loathe and fear. “There’s no place for a strange dog in this village,” he writes. As the villagers persecute the mongrel (it survives a series of shocking ignominies), the corpsman lashes the dog’s fate ever tighter to his own. Mandanipour builds dread as the letters grow increasingly dire. The woman back home frets, “How does a man suddenly become like this?” The corpsman raves that the carved figure possesses a great secret; if only he can decipher its meaning, salvation will arrive.

Many of the stories capture this longing for understanding in a land where clarity is a mirage. History must be built, brick by brick, but violence flattens the landscape. Madness skulks along the periphery of the meticulous records he’s keeping. And who can fault him? Just try to think clearly with the howls of a tortured dog ringing in your ears.

In the title story, an Iranian army company in the Iran-Iraq war contemplates the remains of Nasser, an Iraqi killed in no man’s land. Nasser was shot — apparently by his own army — as he attempted surrender, and Mandanipour is particularly wonderful on the resultant rot:

His clothes decayed, the trichina grew gaunt on his flesh, the sun sapped his fat, and the earth around him turned slimy and black. One day, we noticed his lips had decomposed — it was the worms’ doing — his long teeth were exposed; he looked like he was laughing. Late one night, an animal ripped off his arm and took it away […] the wind took away his putrid stench and the hair on his skull and brought autumn clouds. Rainwater gathered in mortar craters, and the skeleton, still there, with his eye sockets stared at the earth … Snow fell and covered him.

Nasser’s decay rips the veil between life and death in the soldiers’ minds. As the young men observe his transformation, they grow philosophical about their own fate. It isn’t death they fear so much as dying: “We carry with us the image of what he lived through that day.” Nasser’s frantic thirst occupies pages. In a desperate act, one soldier hurls a water jug at his feet only to see bullets burst it the next moment. Every man feels his own raging thirst in those pitiful cries.

In 1981, after graduating from Tehran University, Mandanipour enlisted to go to the front in that same war, and this experience infuses his work. Even in his non-war stories, absurdity, tedium, and florid violence abound. In “The Color of Midday Fire,” a sharpshooter sets out to avenge his slain child. The father “constantly saw the expression on his daughter’s face the moment when the leopard’s jaws opened near her head.” Mandanipour’s characters oscillate between stoicism and struggle, fantasy and certainty. But one creature’s misfortune is another’s salvation.

The captain used to say in battle, the most important thing is not to be caught off guard. But sir, nature uses these moments of inattention as a means of self-preservation. The wind, in an instant of the earth’s inattention, casts a seed in a crevice; the birds are neglectful of the seed and it grows.

The unattended child is the leopard’s good luck. In many of the stories, the worst has already occurred. The drama exists in the aftermath. What story does a person tell in order to keep living?

Mandanipour has written of Iran as “a land of recurrence”: a cycle of uprising, revolution, and repression has gripped the country for the last century.

To erase people’s memories of their history, each regime that has come to power has immediately set out to change the history books taught in schools and universities. […] Perhaps the reason for this repetition is that independent journals and newspapers have been banned and the older generation cannot convey its own experiences to the next generation.

The nine stories collected in Seasons of Purgatory read like dispatches from the front. Just as the lonely corpsman in Guraab wrote his letters home, so the expatriate writer recreates home from a distance. He sifts through military conflict, the repression of women, the forbidden graves of the state-executed, and the shattered minds of children. Storytelling and remembering are subversive acts when power benefits from forgetting.

When daily life resembles a nightmare, the boundaries between the real and the fantastic blur. In “If She Has No Coffin,” Dorna mourns the death of her sister Sara. There’s a split in the family: Sara did everything bad, while Dorna embodies pure goodness. On the morning Sara dies, Dorna gazes at the bitter orange tree in her garden through windows taped against bomb blasts. She travels with her father to the cemetery through empty streets. The reader notes the threat even as Dorna skips past its significance. It’s eerie, the way a child accepts the world as it is. Where, for example, is Sara’s body? Kids are literalists. It’s the adults who lie, who find it impossible to face the truth. Still, reality has a way of asserting itself. As the story of the two sisters begins to fray, Mandanipour reveals the desperation of an entire city through the prism of one family’s distress.

“Seven Captains” is only the third story about stoning that I’ve read after Shirley Jackson and the Bible. In it, an exile returns to visit the site of his lover’s execution. The boy who carried their messages, now a bitter young man, chauffeurs the exile to the square of Seven Captains. It’s a merciless story, built for a world where violence imposes its stultifying will. And yet, there’s a persistence to love, to beauty, that the story celebrates. Mandanipour uses the language of flowers as the lovers’ secret code, evoking Victorian gardens and hazy courtship. Love, like art, grows from cracks in stones, seeds carried there “in an instant of the earth’s inattention.” Love may not save your life, but you will still own yourself when they come for you. For a writer so concerned with the past, Mandanipour is keenly aware of an unwritten future in which wind-scattered seeds might flourish.

The final story of the collection, “If You Didn’t Kill the Cuckoo Bird,” ties together themes of doubling, madness, and betrayal. Two cellmates tell each other their life’s stories over many nights. But to achieve these intimacies, they must first pummel each other in the dark. “Yet, there were times when we — he and I — in the blistering and leaden air of rage, would go at each other simply to quench our thirst for social interaction and fresh associations. When we beat each other — in silence, so the night guard would not notice — we would swallow our groans.” Thus spent, they construct a shared memory palace. In prison, nothing is worth more than a witness. They become each other’s doppelgängers, each man taking ownership of the other’s history as though it were his own. This taking on of another’s story neatly encapsulates the relationship between artist and audience. Like the cellmates, we take on these stories, and for the span of a few hours they become our own.

The Iran of Seasons of Purgatory is a land of contradiction, as all real places are. Mandanipour builds that world brick by brick, constructing out of fragments and whispers, fact and fantasy, a history of a place and a people. What is possible in that moment of the censor’s inattention, what ground has been prepared for the wind-borne seed? Consider Nasser, the soldier shot on his way to surrender:

Weeds had crept up in between his ribs by the time we told and retold all of this to our new commanding officer; some of us may not have been able to tell it all from beginning to end. Some of us are illiterate, many have only a third- or fourth-grade education, a few have high school degrees; some weren’t even around to see that day of reckoning. And so, if we all tell the story, if we tell it together …

Stories exist for the survivors, that they might alter the future. Against the odds, life carries on. There’s nothing more dangerous than that.

¤

LARB Contributor

Lee Thomas won the 2019 Hal Prize in Fiction from the Peninsula Pulse for her story “Young Mother.” Her fiction has appeared in The Hopkins Review, Third Street Writers 2020 anthology, and New Millennium Writings, where she won the XLIX Writing Contest. Thomas has written book reviews, essays, and interviews for The New York Times, The Charlotte Observer, The Chattanooga Times-Free Press, The San Francisco Chronicle, Fiction Writers Review, and elsewhere. She was managing editor at Fiction Writers Review for three years, where she is currently an editor-at-large. She recently finished a collection of short stories. She lives in Los Angeles, cheek and jowl with the desert.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Revolution, War, and Exile: A Conversation with Nino Haratischvili

A major Georgian novelist discusses her newly translated family epic of 20th-century Georgia.

Iran Under Pressure, Again: What a 50-Year-Old Persian Classic Tells Us About the Country’s Predicament Today

Joobin Bekhrad finds new geopolitical relevance in Simin Daneshvar’s classic Iranian novel “Savushun,” first published in 1969.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!