Recontextualizing the Archive: On Anouck Durand’s “Eternal Friendship”

Will Moore on the subtly subversive "Eternal Friendship."

By Will MooreSeptember 29, 2018

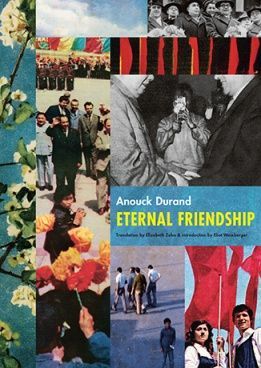

Eternal Friendship by Anouck Durand. Siglio. 100 pages.

IN THE POST–WORLD WAR II political shuffle, China and Albania found themselves joined in an alliance of necessity. Neither country was keen to make cozy with the capitalist West or Stalinist Russia, so pickings were slim. The resulting period of “eternal friendship” between China and Albania lasted as long as their prevailing political ideologies roughly aligned — from around 1958 to the early 1970s. Anouck Durand’s photocomic Eternal Friendship, translated by Elizabeth Zuba, uses this brief moment of attempted political harmony as the context for an invented narrative based on the real-life experiences of Albanian photographer Refik Veseli. During the war, Refik’s family helped the Mandils, a Jewish family, evade Nazi capture. In the process, Refik formed a friendship with Gavra Mandil and learned photography from Gavra’s father, Mosha. After the war, the Mandils resettled in Israel. Due to Albania’s strict censorship policies, Refik struggled to maintain contact with Gavra after the move.

Eternal Friendship pairs a diary-like narrative written in the voice of Refik with archival photographs, a combination that explores the intersection of personal and national history. The book opens in 1970, when Refik visits China at the behest of the Albanian government. He has been dispatched with a delegation of state photographers, ostensibly to learn the trichrome photographic printing process. The trip itself is part of a state propaganda campaign to promote a sense of unity between China and Albania. Refik, who is not a state ideologue, goes with the private purpose of sending a letter to Gavra from China, thereby bypassing the Albanian censors.

Early communist states idealized photography as an inherently socialist art form grounded in science and capable of pure representation. Photography was touted as a tool of the revolution, one that could prove the viability of the communist project. During the period covered by Eternal Friendship, the production and distribution of photography was tightly controlled by the Chinese and Albanian governments. Each state published only images that supported the narratives they intended to tell about themselves — stories of collective strength, advanced industrial technology, and military power. The photographs used by Durand depict parades of people carrying banners with slogans such as “Long live the friendship between the Chinese and Albanian people” and “Welcome comrades of the heroic Albanian people.” Other images show smiling partisans holding rifles or threshing wheat, smokestacks rising from industrial iron latticework, ballistic missiles, and anti-aircraft cannons. Eternal Friendship contextualizes these images in a manner that subverts and repurposes their original function. Propaganda photographs are used not as evidence of China and Albania’s “eternal friendship,” but as evidence of the Chinese and Albanian governments’ attempt to construct such a friendship.

The most obvious level of subversion at work in Eternal Friendship comes from the insertion of photographs into the book’s larger narrative. One picture depicts Refik and the Albanian photographer Pleurat Sulo standing among a line of smiling workers outside of a factory. In context, this photo is transformed from evidence of a strong and satisfied working class into a picture of a man posing so that he can get a chance to mail an unedited letter to his faraway friend.

But Durand also uses text to call out the staged nature of the photographs. Refik’s delegation poses with various locals in a series of photographs accompanied by a caption reading, “The Chinese have provided us with new cameras: a ‘Red Flag’ for each of us, the local replica of the Leica. The scenes to be photographed are also provided.” Elsewhere the book reveals that Albanian photographers had at this point long been using Kodak film, which was superior to the putatively new trichrome printing process they were taught by the Chinese. “We hope they won’t take away our Kodak film,” Durand writes in Refik’s voice.

Eternal Friendship repeatedly juxtaposes personal story with the tendency of communist art to eschew the individual and highlight collective struggle. The book does not include Refik on every page, nor do the pictures follow any sort of continuing action. Instead Durand intersperses photographs of Refik and his delegation with collective partisan imagery. Yet the text never ceases to comment upon each image from Refik’s perspective, explaining the constrained and constructed nature of the trip. Refik was sent to China to learn a new printing process, but he was also sent to generate photographic evidence of political cooperation. He fulfilled the latter mission, but the story of his personal reasons for making the trip undercut the very documentary evidence that he has produced.

Durand also cleverly crops archival images to invoke his motif of individual versus collective. One of the first pictures she includes is a painting of the two nations’ leaders, Mao Zedong and Enver Hoxha, clasping hands. The accompanying text reads, “The friendship of brotherhood … solid like granite … unites our two countries. China and Albania.” This is most probably the intended message of this painting at its creation. The following page is a photograph of a stadium, filled with people, above which hang the portraits of each country’s respective leader. Durand divides this image into two panels, inserting a thin white gutter through the center of what was once a single image, separating the leaders’ portraits. On the following page, Refik is introduced with the same technique. What appears to be a larger photograph of a parade is cropped to focus on individual marchers to whom we are introduced: Refik Veseli, Pleurat Sulo, and Katjusha Kumi. The text, in Refik’s voice, comments on the strangeness of being “on this side of the camera.” In this way, Durand invites us to examine the individuals within the photograph of the collective whole.

Finally, the very use of these photos is subversive, as both governments attempted to destroy these archives when the Chinese-Albanian relationship deteriorated and each sought to erase the evidence of their former relationship. Some pictures used by Durand bear marks of the attempted destruction in the form of scratched-out and burned faces. Once the state is no longer interested in publishing (or even preserving) the images, their function switches from propaganda to evidence. In the 1970s, the farce of an eternal friendship between China and Albania might have been believable. But presented in the context of the 21st century, knowing that this period of cooperation barely lasted 20 years, the claim deflates.

The latter portion of Eternal Friendship is devoted more exclusively to Refik’s history and his friendship with the Mandils. The images in this section include pictures from Refik’s personal collection — sentimental photographs and individual portraits that one might find in a family album. Instead of the plain white background and grid-like placement utilized in the first part of the book, these images appear as though imprecisely pasted atop blue construction paper. While the pictures are aesthetically placed, they are neither perfectly aligned nor divided by consistently-sized gutters. This portion of the book resembles a scrapbook more than a comic book. Durand also includes a letter written by Gavra nominating Refik’s family as “Righteous Among Nations,” which ultimately enabled the two to reunite in 1990.

This letter of nomination is, like the state propaganda photographs, a sort of fabrication. The sentiment may be heartfelt, but as with any political document, it is molded toward a specific purpose. In this respect, it parallels the photos in this section, which one might expect to be more personal than those documenting Refik’s visit to China, but which remain just as beholden to ulterior purposes. Refik’s family photographs are staged: the children are corralled to sit still just like the factory workers. The subjects are carefully posed and smile for the camera. Ironically, there are more seemingly candid shots in the first portion of the book.

As with the propaganda photos, the personal photographs contain multiple meanings that Durand sets out to reveal. One image shows Gavra and his sister standing in front of a Christmas tree. This was taken by their father to be used as advertising for his photo studio, and later repurposed as evidence of their Christianity designed to forestall Nazi harassment. A picture of Mosha and Gavra standing next to one another and smiling appears at first to be a generic family photograph. Its true import is revealed, however, by the accompanying text: “With Mosha (left) finally out of hiding in the basement: freedom!” Without these captions, a viewer would be unlikely to discern that these seemingly mundane pictures depict years of elusion and evasion — hiding in cramped basements, false identities, and even time in prison. One of the final images in the book was taken in 1990, when Gavra and Refik are reunited at last. It is among the only seemingly candid photographs in this section. Other people in the photo are not looking at the camera, and one person (either Refik or Gavra) holds his hands above his head in celebration, even though this obstructs the composition of the photo.

In this way, Durand primes us to rethink the propaganda photos she has shown us earlier. Even though we know these photos were staged, this does not change the fact that these people did meet and stand among one another. The artificial impetus of these meetings need not necessarily have precluded authentic connection. Nothing prevented Refik from enjoying the company of the factory workers. Put another way, if the family photos are as staged as the propaganda photos, then it follows that the propaganda photos are at least potentially as authentic as the family photos.

Eternal Friendship is a project of archival recontextualization. It does not merely revise or define the meaning of the images Durand selects, but situates these pictures within multiple contexts. The state propaganda photo offers, in addition to its intended purpose, a glimpse of Refik’s visit to China and evidence of the state manipulation of history. The studio advertisement becomes a tool of escape and subversion. A nomination letter functions as a political plea, but also serves as an authentic testament of friendship. In this context, it becomes impossible to definitively state what the archive shows about the past. While telling a compelling personal story of friendship, Eternal Friendship also explores the flexible nature of the image. Photography constructs histories, about ourselves and about our societies. But what a photograph reveals changes with time, and it is often not a single story.

¤

LARB Contributor

Will Moore is a PhD candidate at the University of Missouri, where he studies nonfiction, essays, and comics. His comics, interviews, and critical reviews have been published in The Rumpus, The Missouri Review, and ImageTexT.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Irrational Authoritarianism: Ismail Kadare’s “The Traitor’s Niche”

Ani Kokobobo on an allegory of modern authoritarianism set in the Ottoman Empire.

A Silver Thread: Islam in Eastern Europe

Jacob Mikanowski traces the silver thread of Islam in the tapestry of Eastern European culture.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!