Prague Always, Always Wins: On Daniela Hodrová’s “City of Torment”

A surreal Czech masterpiece that plumbs the magical depths of one of the world’s great cities.

By Agnieszka DaleMarch 31, 2022

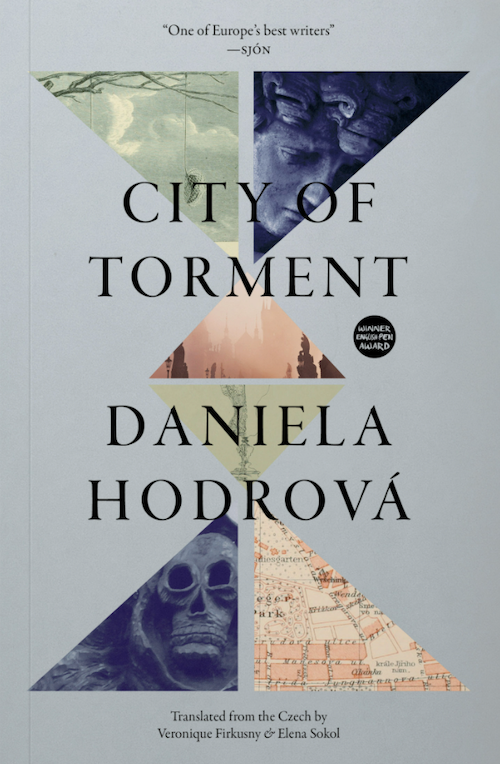

City of Torment by Daniela Hodrová. Jantar Publishing. 620 pages.

I REMEMBER MY FIRST visit to Prague very well. I was a Polish teenager, and I went to Prague to see the Rolling Stones. They came because Václav Havel had asked them personally. He didn’t send a formal invitation; rather, he invited Mick and Keith for a few beers. The Stones loved it, of course, and quoted the message to the press. They skipped Poland on that world tour — a country that, in light of Havel’s fun invitation, probably seemed like a pompous and humorless neighbor. So, my school friends and I traveled to Prague, the most beautiful city in the world, as recently voted by readers of Time Out magazine. Its beauty, which had survived many wars, was both striking and surprising to us (especially since 90 percent of Warsaw’s original buildings had been destroyed in World War II). The Czechs always treated their capital as if it were the central character in their lives — Prague was always a human!

Daniela Hodrová’s Prague, too, has ears and eyes, and often a womb. Sometimes, it is a type of monster, haunting its inhabitants. Other times, it is a parlor inhabited first by Czech Jews then by a German family. A beautiful, sensual place, it frequently changes lovers. A “moving game of meanings and references,” as Hodrová notes in her 2006 book, The Sensible City, Prague is inhabited by both the living and the dead:

I am the pantry, the chamber of resurrection […] of shivering small-time thieves and masturbating youths. […] I am the chamber of suicides, and the chamber of dreamers. […] I belong to all those who enter me and soil me with their secret sins, with their petty vices. I take them all indiscriminately into my decrepit arms, press them to my hermaphrodite body, for I have lost all female charms in my old age, my source of femininity dried up long ago. […] I am a wasteland. […] I am what my visitors make of me, they come to gratify me as they would an aged harlot, only in moments of helplessness and anxiety.

London-based publisher Jantar has been bringing out Hodrová’s work in translation for over a decade. First, they released her mixed-genre “guidebook” Prague. I See a City… in 2011, then her 1991 novel, A Kingdom of Souls, in 2015. Now Jantar is putting out its most ambitious effort yet: a superb translation by Véronique Firkusny and Elena Sokol of a loose trilogy of novels, City of Torment. The novels were first published separately in the early ’90s by a provincial Czech publisher, to great critical acclaim but very little sales. When, in the late 1990s, they were rereleased as a beautiful compendium, with the elusive city of Prague at its center, Hodrová’s profile increased. She was awarded the Franz Kafka Prize in 2012; her book Točité věty (Spiral sentences) won the most prestigious Czech literary award, the Magnesia Litera, in 2016; and her academic work on the theory of the novel has been well received internationally, particularly in France and Russia.

Hodrová was never associated with the dissident movement in the former Czechoslovakia, and none of her writing was published in the underground but half-tolerated samizdat form. As a scholarly woman writing in a rather recondite literary tradition, she probably wasn’t taken very seriously by more “political” (male) authors, and she didn’t really care for them either, it seems. As it turns out, all this has stood her in good stead. The many “banned authors” of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s were finally published in the early 1990s — and then the world basically lost interest in them, paving the way for “new voices” to emerge, including Hodrová’s. After she was awarded the Kafka Prize, whose winners include the likes of Harold Pinter and Margaret Atwood, Hodrová has even been proposed a few times to the Nobel Committee.

Although City of Torment is an experimental work, it is not a hard read. In the opening scene (a suicide, it seems, though this fact is not directly mentioned), the protagonist, Alice, falls out of a window, dies, is buried, and reconnects with her dead ancestors in a matter of seconds, as if she were Alice in Wonderland tumbling down the rabbit hole:

Alice […] would have never thought the window of her childhood room hung so low above the Olšany cemetery that the body could travel the distance in less than two seconds. […] Alice enters and sees her grandmother at the table, tears streaming down her cheeks. The table is spread with the Sabbath tablecloth. It occurs to Alice that maybe one day someone will have a dress made of it, a Sabbath dress.

In this very first scene, Alice’s faith and hope have been exchanged for death. This is Alice’s decision; she has agency, and she acts. She has not given up a life of possessions or material happiness; she has surrendered her life. What that fully means is revealed in the ensuing 600-plus pages. On one level, the story is a very personal account of things that happen to Alice during her short life, especially the goings-on she witnesses in her apartment building. On another level, it is a historical survey of Czech lands that begins, vaguely, in the first millennium and ends with the Velvet Revolution in November 1989. It’s also saturated with literary allusions — to Virginia Woolf, to Dante, to Tennessee Williams, to the Czech poet Karel Hynek Mácha … Have I missed anyone?

Over the course of the story and the complex history it recounts, Prague throws all sorts of grenades into the paths of its citizens. How Alice’s parents and neighbors absorb the explosions or return the grenades (with interest) becomes another layer in the life of the city. Actions taken hundreds of years earlier bring new outlooks and outcomes. History returns and bites hard. As Alice waits for a happy ending, her neighbors struggle to survive and love one another, while the city’s beautiful architecture — even the gargoyles on its cathedrals — come alive. Prague’s citizens might find some space to thrive for a time, but the city always wins.

City of Torment is magic realism on steroids. People turn into ghosts, then they become pupae. Characters begin to merge. Souls rustle in vases. Wings beat inside pillowcases. Fingernails on statues turn into claws. The dead swap bodies with one another, are spun and transformed into statues, are heard speaking softly in the pantry. Alice’s grandmother turns into a swan, her grandfather into a moth.

Souls cling to life through things, or rather through relics of things. As if these relics hold some kind of promise of being reborn, the pledge of a new life. There is, after all, the aura, that extraordinary fluid surrounding and animating things, which the dead perceive much more strongly than the living. To touch things is almost like touching life itself.

As I read further into the trilogy, I became aware of the distinctly feminine voice, an observing and structuring consciousness that grows increasingly more self-reflexive, openly exploring the relationship of the author to her text. The autobiographical connections are most apparent in the last and shortest novel in the sequence, Theta, when Hodrová touchingly describes the lives and deaths of her parents, friends, and husband, and what those lives meant to each other and to her. Now their ashes are mixed together in death:

That one, whose ashes had flown across the ocean and on 11 June 1985 at 10.50 a.m. were scattered by the hand of the Olšany sower, now steps lightly, she almost floats. At the end of the meadow she even takes a little leap (isn’t that called a jeté?), at the same time her legs come together in the air — that of course is an assemblé. She’s dancing — wonder of wonders. I’m probably dancing because my ashes have intermingled with the ashes of that ballerina, they also — this sounds very much like a novel — traveled across the ocean to Olšany, thinks Milada Součková, actually now half Yelena Rimská. It would be better to call her the Scattered One, because now she’s the writer and the ballerina in one and the same figure.

The novels also became a major part of the lives of their two excellent translators. For Véronique Firkusny, the journey began with her mother in the 1990s as they translated fragments of A Kingdom of Souls into English. The task continued in an intense six-year collaboration with Elena Sokol to translate and polish all three novels into this masterpiece.

It is difficult to disagree with the Icelandic poet Sjón when he describes Daniela Hodrová as “one of Europe’s best writers.” I could add something like, “one of the best writers you have never heard of,” but that really is not enough. This book can change your life, like it changed mine. Reading City of Torment has become an important and personal exercise in reading creatively, openly, and lightly — a practice we all need to learn.

¤

LARB Contributor

Agnieszka Dale (née Surażyńska) is a Polish-born London-based author conceived in Chile. Her short stories, feature articles, poems, and song lyrics were selected for Tales of the Decongested, The Fine Line Short Story Collection, Liars’ League London, BBC Radio 4, BBC Radio 3’s In Tune Live from Tate Modern, and the Stylist website. In 2013, she was awarded the Arts Council England TLC Free Reads Award. Her story “The Afterlife of Trees” was shortlisted for the 2014 Carve Magazine Esoteric Short Story Contest and longlisted for the Fish Short Story Prize 2014. Her debut collection of short stories is Fox Season (Jantar Publishing, 2017).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Spies in Neverland: On Ana Schnabl’s “The Masterpiece”

A novel about illicit love and betrayal in 1980s Slovenia.

Friday Prayers: On Aslı Biçen’s “Snapping Point”

Aslı Biçen’s novel is a political allegory of Erdoğan’s Turkey that works in other contexts, too.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!