Pier Paolo the Anti-Fascist: On Criterion’s “Pasolini 101” Collection

Conor Williams reviews “Pasolini 101,” the new Criterion Collection box set on Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini.

By Conor WilliamsJune 22, 2023

THIS YEAR MARKS the 101st anniversary of the birth of the radical Italian artist Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922–75). A painter, a poet, a novelist, and a public intellectual, Pasolini is best known and most celebrated for his contributions to cinema. This legacy was also a wildly controversial one. Pasolini’s final film, Salò, or The 120 Days of Sodom (1975), was a deeply disturbing and fiercely political portrayal of the fascist elite that has since been banned in several countries. Pasolini, who was openly gay, was brutally murdered by a young gigolo in 1975, three weeks before the film opened, and many believe that this attack was a coordinated retaliation against his communist politics.

Last year, John Waters told the Los Angeles Review of Books about visiting the scene of the crime. Pasolini has long been a beacon for the Pope of Trash—he’s said that Salò is the one film he wishes he could have made. Waters, retains a comparable notoriety of his own in cinema history, doesn’t believe that Pasolini’s demise was an inside job, referring to it instead as a “bad night”: “Did [the killer] put out that night before he crushed Pasolini’s testicles, ran over him, and set fire to the great director’s dead body?” muses Waters in the tribute he recorded at the site, Prayer to Pasolini. “I bet he did.”

These days, Pasolini has faded slightly from the cultural consciousness. This isn’t to say that he is unknown, but rather that the immense breadth of his artistic body of work has been overlooked and understudied compared to his counterparts in postwar European cinema, such as Federico Fellini or Ingmar Bergman. Those with a passing familiarity likely know Pasolini through Salò, and that film’s reputation has ballooned through meme culture to the point where viewers might expect it to be akin to something like The Human Centipede (2009) or the snuff-like shocker A Serbian Film (2010).

While many sequences are indeed revolting, Salò is not simply empty provocation; it’s a film of substance, and Pasolini’s filmography is much deeper and richer than just one film. Some of this falls on the Criterion Collection, as Salò was their main stand-alone release from the director for a long time and therefore appeared to be the most representative film from his oeuvre. A similar strange phenomenon has clouded the work of Nobuhiko Obayashi. His 1977 film House has become a huge cult classic thanks to Criterion, but the rest of his films made during his 60-year career have barely been given attention. These hang-ups illustrate the constraints of the canon.

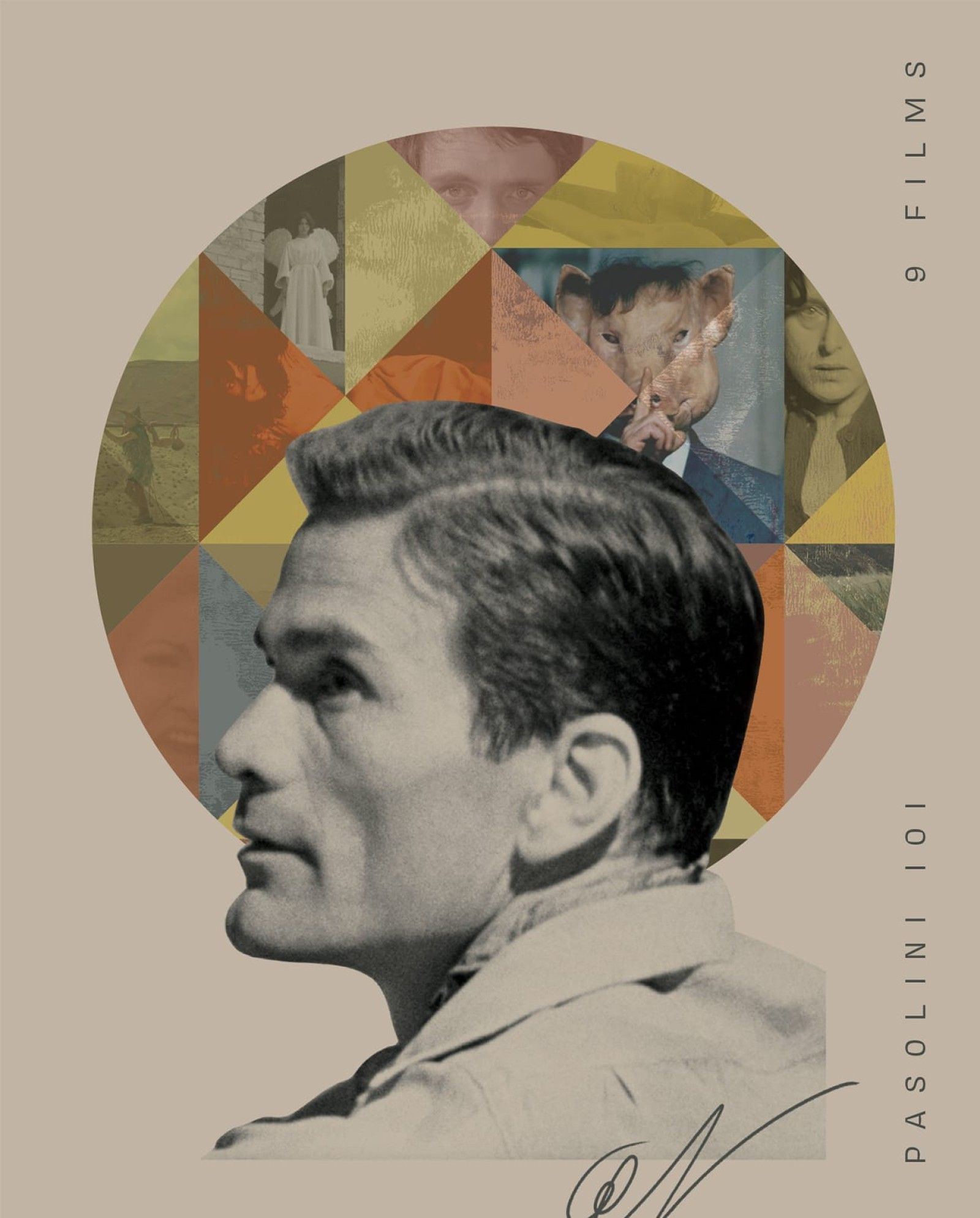

Thankfully, this June, Criterion is releasing Pasolini 101, a box set of nine of the director’s films ranging from the iconic to the obscure. The release’s title has a clever double meaning: it marks one year past the artist’s centennial and also serves as an introductory survey of his work.

Two of the films included are Medea (1969), Pasolini’s collaboration with opera singer Maria Callas, and The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964), a neorealist take on the life of Jesus Christ, with dialogue taken directly from the Bible. Pasolini’s work often involved religious themes, and Gospel was not the first of his films to feature the son of God. That honor goes to his Orson Welles–starring short film La ricotta (1963), which so provoked Italian authorities for its supposedly sacrilegious nature that the filmmaker was punished with a jail sentence, which he got out of by paying a fine. Gospel, in contrast, was a deeply respectful portrayal of Christ, to the extent that even the official newspaper of the Vatican has lauded it as one of the greatest films of all time.

Likewise enamored with Pasolini and his oeuvre, filmmaker Abel Ferrara (who, like Pasolini, isn’t technically Catholic, but whose work bluntly bears the influence of that religious tradition) released an excellent biopic of the Italian artist in 2014. In it, Willem Dafoe coolly inhabits Pier Paolo’s style, subtle warmth, and sharp wit. The film focuses on Pasolini in the final stretch of his life, planning for his next project after Salò. In a 2013 interview, Ferrara professed that he had planned to make a film in the 1990s about a female version of Pasolini starring the former’s collaborator Zoë Lund, but it never came to be.

While Ferrara did not end up exploring such inversions of gender within the framework of depicting the director’s life, Pasolini himself was often eager to demonstrate the complexities of romance, gender, and eroticism in his films, most clearly in Teorema (1968) and Love Meetings (1964). In the former, the overwhelmingly handsome Terence Stamp stars as a mysterious visitor who descends upon a wealthy family’s palatial estate. We don’t know who he is, where he’s come from, or what his motives are. The significance of these queries seems to quickly dissolve for the family, however, as they are immediately overcome with intense attraction to the visitor. One by one, each member of the household falls for him. Under this hypnosis, the patriarch of the house turns his factory over to the workers. It’s a sexy, supernatural, and cleverly anti-capitalist tale.

Operating outside the narrative constraints of a fictional story like Teorema, Love Meetings is particularly exciting, because we see Pasolini himself taking to the streets with a microphone in hand. He quizzes the children of Palermo, asking them how babies are born. (Storks, of course.) He tries to get men and women to open up: Have you been to striptease shows? Is sex personally important to you? Would you consider working in prostitution? Do women deplore men who’ve been with prostitutes? What do you know about homosexuality? Are you easily scandalized? The result is reminiscent of Chronicle of a Summer, the French cinéma-vérité film that came out three years prior, which asked the people of Paris, “Are you happy?” It’s fascinating to watch Italian townspeople of the 1960s ruminate on the ideas Pasolini confronts them with, and it reveals just what has and hasn’t changed, both then and now, regarding public attitudes toward sex and sexuality.

“What attracted me to [Pasolini’s] work was his insane Catholicism, his love of the underclass and his unpredictableness,” Waters remarked on the podcast Bullseye with Jesse Thorn. “You know, right in the middle of the ’60s, he was against the hippies and for the cops, ’cause the cops were working-class and that’s what he was for as a communist. And the hippies were rich kids.”

Waters is referring to a 1968 poem by Pasolini, “The PCI to Young People”:

When yesterday at Valle Giulia you and the policemen were throwing blows, I sympathized with the policemen! Because policemen are sons of the poor, they come from urban or rural outskirts. […]

They are twenty, your age, dear friends. We agree, of course, to be against the police institution, but try to fight against the Judges, and you’ll see what happens! The young policemen you were hitting […] are from a different social class. At Valle Giulia, yesterday, there was a fragment of class struggle: you, my friends, (although in the right) were the rich, and the policemen (although in the wrong) were the poor.

In an article titled “The Police vs. Pasolini, Pasolini vs. The Police,” Wu Ming explains, “The man who writes this verse in June 1968 has already gone through four arrests, 16 charges and eleven trials, in addition to three assaults by neofascists (all dismissed by judges) and a police search of his apartment, to look for firearms.” Ming later asks:

Why such a persecution? Because he was homosexual? He was certainly not the only one amongst artists and writers. Because he was homosexual and communist? Yes, but this isn't enough either. Because he was homosexual, communist, and expressed himself openly against the bourgeoisie, government, Christian Democracy, fascists, judges, and police? Yes, this is enough.

Pasolini’s seeming ideological blurriness is impishly relished—and willingly misconstrued—by wannabe-transgressive types today. Those in search of a provocative new personality trait have embraced the label “tradcaths” and are apparently converting to Catholicism. (One high-profile convert? Actor Shia LaBeouf, who stars in Abel Ferrara’s 2022 film Padre Pio as the titular saint.) As The New York Times put it in a headline last year, “New York’s Hottest Club Is the Catholic Church.”

Elsewhere, in a recent profile of tradcath media personality Dasha Nekrasova, writer Mikkel Rosengaard dubbed her type “the femtroll,” stating,

In the 1960s, the hippie reacted against the stifling conformity of the lavender scare and the hypocrisy of McCarthyism. The femtroll is reacting against the cancellation of museum shows, the public shaming of artists’ sexual mores, the online policing of microaggressions, all that [bourgeois] virtue signaling—in short, against the moral panic of the Trump years.

What any of this is actually referring to is beyond me, as Rosengaard doesn’t elaborate further.

What I can point to is Nekrasova making a stink about Chicago’s Music Box Theatre canceling a screening of her friend and collaborator Betsey Brown’s 2021 film Actors. The cinema axed the screening after several complaints about the plotline being transphobic. In response, Nekrasova took to Twitter to personally insult Jane Schoenbrun, the transgender filmmaker behind the acclaimed film We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (released the same year) and one of the most notable critics of Actors; Nekrasova went so far as to call Schoenbrun a “tyrannical loser” and a “lunatic.” Nekrasova’s Twitter followers replied with transphobic remarks targeting Schoenbrun, not doing much to disprove the latter’s allegations. Lacking a substantive defense of the film, resorting to crude comebacks, Nekrasova sounds similar to Pasolini’s fascist critics who attacked his homosexuality instead of offering critiques of his work.

Rosengaard’s piece suggests that Nekrasova could be the new “it girl” of the avant-garde, but given her reverence for an institution notorious for its abuses—not unlike what plays out in Pasolini’s Salò—and given that she amplifies transphobia at a time when the LGBTQ+ community is under attack; given that she has spent time with Alex Jones, Steve Bannon, Roger Stone, and the New York Young Republican Club, an organization friendly with alleged sex trafficker Matt Gaetz, Brazilian ex-president Jair Bolsonaro, conspiracy theorists Marjorie Taylor Greene and Jack Posobiec, and white supremacist Peter Brimelow; given all these things, it would be more accurate to call Dasha Nekrasova the new it girl of the alt-right.

Pasolini anticipated this slippage as early as 1973, describing in one of his essays this Dimes Square/tradcath/femtroll/whatever-you-want-to-call-it’s rightward turn to a tee. “The subculture in power,” he writes, “absorbed the subculture that was in opposition and took possession of it with devilish ability, and passionately made of it a fashion that, if we cannot really call it fascist in the classic sense of the word, is after all extremely right-wing.”

That pseudo-intellectuals are occupying a slice of gentrified Chinatown maybe doesn’t spell immediate danger, but fascism is here, plain and simple. It has blossomed in the United States, thanks to the failure of neoliberalism and the encouragement of reactionary figures in our government and media. Proud Boys are gathering in my Long Island hometown, their mobs shouting threats outside our public library and school board meetings. Our moment demands that we study the words and work of Pier Paolo Pasolini. The Italian master has much to teach us, not just about how to make films that are stylish and thoughtful, but also about how to take a meaningful stand against evil in our daily lives.

The release of Pasolini 101 is an opportunity for the uninitiated to discover the work of a daring, prolific artist, and it’s a welcome celebration for fans of the Italian auteur in the form of another handsome collection from Criterion. While one can now enjoy a gorgeous restoration of Pasolini’s work, it is important to remember that one can and should see them on the big screen as well. In coming together at the cinema, we can authentically appreciate the spiritual sense of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s revolutionary oeuvre, as well as its communist ethos.

¤

LARB Contributor

Conor Williams is a filmmaker and writer who has contributed to Interview Magazine, BOMB, and elsewhere. He currently works at BAM Rose Cinemas.

LARB Staff Recommendations

What the Center Holds: On Carl Elsaesser’s “Home When You Return”

Hannah Bonner considers the smudge in Carl Elsaesser’s 2021 film “Home When You Return.”

Identifications and Their Refusal: On Alice Diop’s “Saint Omer”

Francey Russell reviews Alice Diop’s film “Saint Omer.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!