Only in Her Head: On Mona Awad’s “All’s Well”

A compelling new novel about a college theater troupe, a Faustian bargain, and italics.

By Ian Ross SingletonSeptember 22, 2021

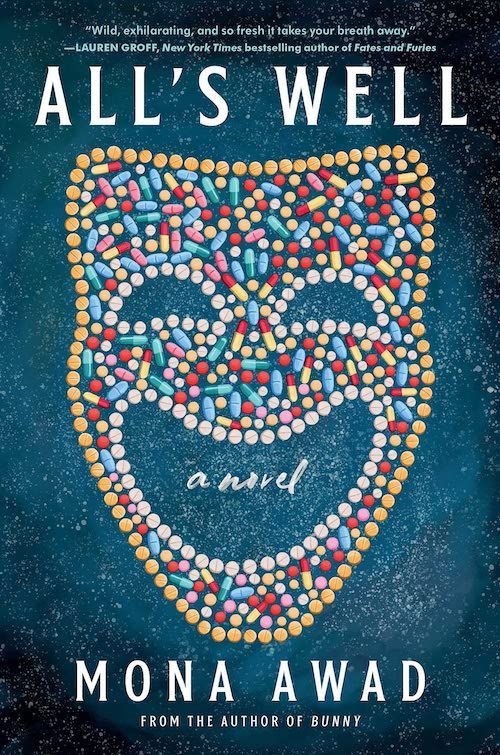

All’s Well by Mona Awad. Simon & Schuster. 368 pages.

MONA AWAD’S LATEST NOVEL, All’s Well, about a college production of William Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well, begins with the narrator’s description of her pain as a fat man standing on her foot, holding her down while he mocks her job as a professor of theater at a “dubious college.” The fat man is, of course, a figment of her imagination, and his italicized dialogue is as well. The italics recur throughout the novel to indicate what the narrator, Miranda Fitch, thinks other characters are feeling or saying about her when she’s not around. Perhaps this sense of what people would say if they weren’t so guarded, always acting the role of what’s expected of them, becomes an occupational hazard for a director.

Some examples:

Sorry, Miranda, but we all feel. […] None of the students will look at me.

[…]

“Can someone please tell me what’s going on, please?” I ask this kindly. Inquiring, merely inquiring. Like I’m curious.

You know what’s going on, Miranda. You see the script in my hands that is not your script, that I’m holding in such a way that the title is visible to your eye.

[…]

“Well, if you need my help, you just call. I’m right across the hall, you know.” Watching you. Willing you to fail.

Italics are traditionally used for emphasis. And it’s certainly true that what’s italicized here would be emphatic were these comments really made. The italicized passages not only give a deep view of Miranda’s interior mind, but they also ring true. They demonstrate the sensitive ear — perhaps verging on paranoid but nonetheless acute — that Miranda has for what motivates the remarks characters actually do make. For a director like herself, such language must show up in notes taken on scripts, indicating a layer of communication that is suggested but never spoken, yet implied by all other aspects of a performance, expressed not with the actor’s voice but with their body.

So, it must be particularly frustrating to Miranda that her bodily pain, the consequence of falling off the stage during another production of All’s Well, isn’t taken seriously by anybody. Miranda is an actor, after all. She’s “being dramatic,” as is so often said about women who are suffering.

The italicized passages do ring true, yet there’s no way to say that, unlike memories (and the italics also indicate remembered dialogue), they are anything more than an invention of Miranda’s imagination. All of Miranda’s doctors and physical therapists have said of her pain that “[i]t’s all in your head.” That sentence then becomes, It’s all in your head, and proceeds to haunt Miranda, because what’s in her head nobody else knows. Her real suffering is something she experiences alone.

That is until she finds herself in a Faustian bargain with three strangers who seem to be able to hear this italicized language locked — like her pain — in Miranda’s head. As such Mephistophelian strangers tend to do, they offer her supernatural power — the power to make her pain known.

As Miranda goes from helpless victim of her own “imagined” pain to formidable master of her theater troupe, much of the italicized language disappears. There is no longer any need for the solace this inner voice gave her during her lonely suffering. Now this silent commentary, like her formerly isolated pain, is something she can not only sense but also say. She can be as honest as she pleases because of her new power. No longer are her conversations filled with subtle barbs lurking beneath seemingly straightforward statements. Not only is Miranda’s pain now real to others, but it becomes their experience too, no longer hers alone or even at all. The pain has dissipated, and she enjoys the cheery privilege of the healthy now. Instead, her enemies are burdened by her former pain. And it’s their turn to suffer alone with no validation of what they’re feeling.

This transition happens through dialogue exchanged between the female characters. The conversations between Miranda, her assistant Grace, her student Briana, and adjunct teacher Fauve are, at the outset, filled with secret insults directed at Miranda. Now, she directs them back at Briana, Fauve, and even her ally, Grace. In addition, she takes on the role of giving motherly solace to Ellie, her understudy-turned-star Goth student. This parental role will be familiar to readers who are also teachers. We begin to hear about Miranda’s mother — a disturbed woman, also a fierce champion of her daughter’s theater career. Memory and imagined dialogue blend together to fill later pages with italics and push out non-italicized reality.

But me, I’m not ever tired. I slept a little last night in the sea.

In the sea?

Oh it was lovely. Have you ever slept there? The waves are just like a blanket. The black waves give you dark green dreams.

Professor, you’re bleeding.

When this dissolution of reality moves from internal dialogue to actual events, the situation becomes blurry. Readers don’t ever learn if Miranda truly gets away with it, if her vengeance is real or not, and whether she’ll have to pay the piper or else risk a fate worse than her former painful loneliness.

Meanwhile, the male characters don’t change much or at all, really. Hugo, the set designer with a troubled past, becomes enamored with Miranda despite being merely a rebound from her ex-husband. Trevor, Briana’s boyfriend, who plays the role of Bertram in the production, flies easily to Ellie once she takes over the leading role of Helen, Briana’s role when she was healthy. Throughout the story, men are pawns to the queens dominating the conflict. The only men with any real power seem to be the three Mephistophelian strangers, who only enter the novel when they please and are seen only by Miranda.

Similarly, as Miranda’s power grows, she begins to gain a reputation of her own:

[Briana] raises a hand. It shakes, can you believe this? It trembles as she points her little white finger at me. “She,” she says.

“Professor Fitch,” the dean offers.

“She made me sick.”

Very soon, Miranda is being called a witch. Now she’s the one ignoring a woman’s pain. The epithet “witch” is, of course, a loaded one in our culture’s history. The complementary phrase “witch hunt” comes from the time of the Puritans but became a descriptive term for the McCarthyite persecution of “communists” before it finally came to describe the “victims” of the #MeToo movement, the men who wielded their power to take sexual advantage of women. Some feminist writers have sought to reclaim the term, and All’s Well would appear to demonstrate that point. For Miranda to gain any kind of power, she must resort to supernatural means. And there is another exception to men playing the role of pawns: the dean. Though he is manipulated by the three strangers, his real power remains unaffected. Before the Faustian deal was struck, the dean was about to shut down Miranda’s play. All her doctors and therapists, those who always told her the pain was “in her head,” were men. In reality, despite the supernatural battles taking place among the women, men remain in power.

As in Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, the classic novel about a Faustian pact, the supernatural powers granted to Miranda include the ability to turn the tables. This genre of literature provides the readerly satisfaction of a righteous vengeance. Bulgakov’s protagonists took their revenge against the Soviet Union, specifically the apparatchiks in the cultural sphere of theater and the arts, and Miranda takes hers against Briana, Fauve, and the dean.

But her “revenge” against the dean doesn’t seem to bother him much. Whether there is any real resolution to the psychic drama of All’s Well remains unclear. Miranda laments: “Wish I could leave here. Drive to Hugo sitting on my front steps, waiting for me like a dream on the other side of this. But there is no other side of this, Ms. Fitch.” Suddenly, the italicized language is back, but it is now the voice of the supernatural forces that aided her in her vengeance, only to negate her reality.

Perhaps Mona Awad is putting the reader in the position of victim, someone who experiences pain and has no recourse to any real resolution. The setup resembles the writer’s deepest dilemma: what if all her careful plotting, her effort to resolve things for the reader, turns out to be a trick of her imagination, is only in her head?

¤

Ian Ross Singleton is author of the forthcoming novel Two Big Differences.

LARB Contributor

Ian Ross Singleton is author of the novel Two Big Differences (MGraphics). He teaches writing at Baruch College and Fordham University. His short stories, translations, reviews, and essays have appeared in journals such as Saint Ann’s Review, Cafe Review, New Madrid, Asymptote, Ploughshares, and Fiction Writers Review.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Auspicious Conflagrations: The Heat of Women’s Anger

Bean Gilsdorf joins the chorus of women speaking about their anger, so that they can do something about it.

LARB Lit: Woman Causes Avalanche

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!