On the Gender Trouble of “Loving Highsmith”

Rox Samer reviews the documentary “Loving Highsmith” and highlights the trans resonances in Patricia Highsmith’s life and work.

By Rox SamerFebruary 16, 2023

For Robert Deam Tobin (1961–2022), who also loved Highsmith.

¤

TWO MINUTES into her new documentary Loving Highsmith (2022), filmmaker Eva Vitija explains, “Like many other filmmakers, I was immediately drawn to Patricia Highsmith’s writing.” I myself only developed a taste for Highsmith in the wake of Todd Haynes’s Carol (2015), after realizing that a single author was responsible for the novels behind three — make it four — of my favorite films. (At first, in addition to Haynes’s film, it was Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train from 1951 and Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley from 1999, but now Wim Wenders’s 1977 adaptation The American Friend also ranks high on the list.) I was joining a long line of film scholars, critics, philosophers, and cultural historians, thinking far outside the realm of postwar literature, that were curious about the novelist who — through desire-driven plots, as if she were already writing for the screen — so exquisitely upended the Cold War ideology of the middle class as bearers of normalcy and national strength.

Sure, there exist decades-long debates as to whether Hitchcock’s film — with its not-so-innocent but nonetheless ultimately incorruptible Guy Haines (played perfectly by doe-eyed bisexual Farley Granger) — betrays the novel’s narrative conceit of a-murder-for-a-murder and, in so doing, neutralizes Highsmith’s argument for the potential for violence and queerness lurking in all of us. (Thanks, Production Code!) Likewise, as enthusiastic fans and skeptics alike were quick to point out, Matt Damon’s heartbreakingly delicate Ripley — who, under Minghella’s direction, sensually croons “My Funny Valentine” alongside Jude Law’s golden Dickie — is a far cry from Highsmith’s cool, guiltless Ripley. Regardless of where you come down on film adaptations and the cultural work they do in their own contexts and media, it is hard to disagree with Wenders’s point that you learn about yourself as you read Patricia Highsmith (including, most astoundingly, your own fears and cowardice), and that film, as a medium that treats identity so searchingly, ideally fits her stories; it is a pinky that finds its ring with Ripley, a medium “flung out of space” with Carol.

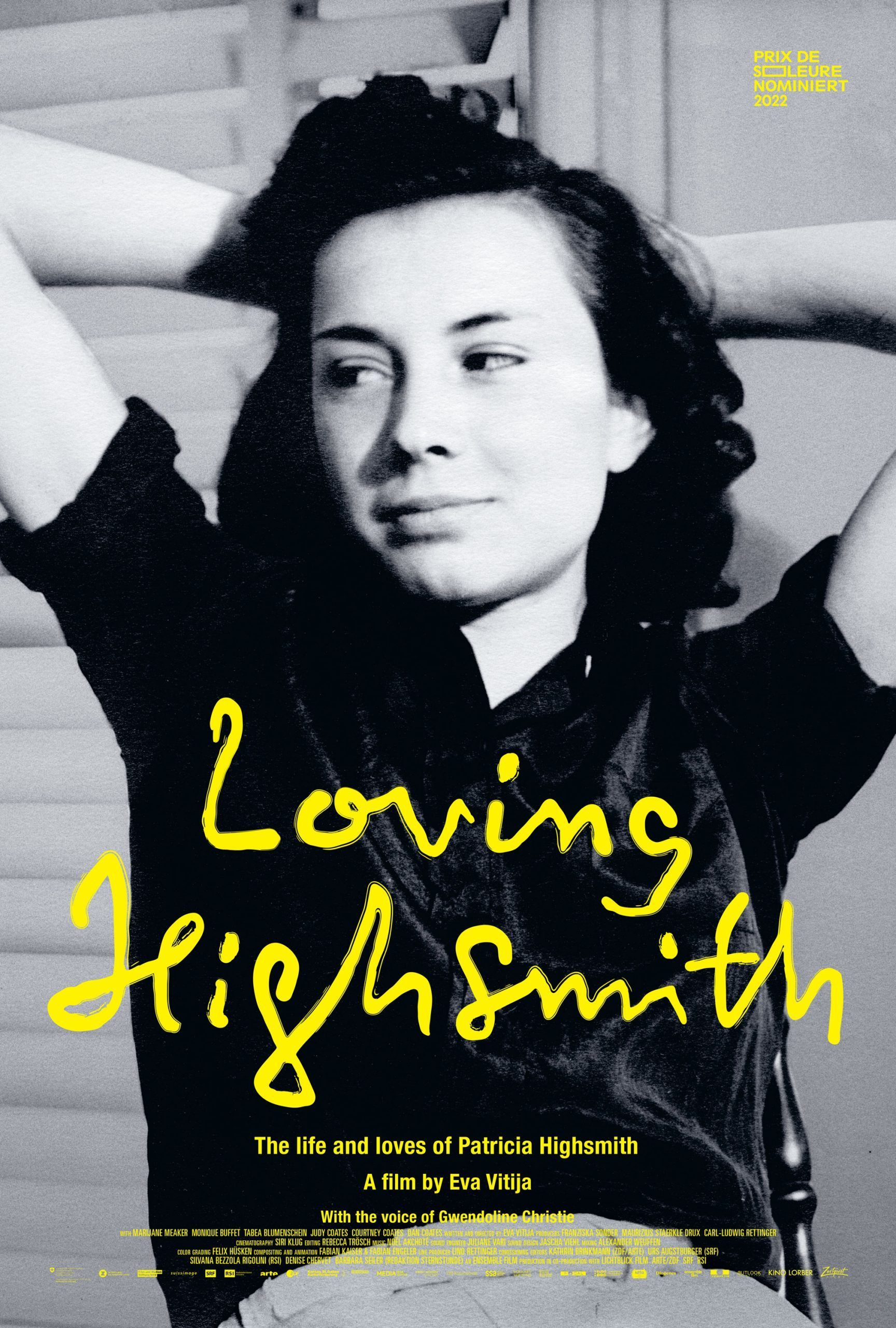

A documentary about Highsmith the person as much as Highsmith the author, Loving Highsmith anchors excerpts from adaptations by Haynes, Hitchcock, Minghella, and Wenders to interviews with Highsmith from across her career. (Highsmith found being interviewed “a profound indignity” but gave dozens nonetheless.) The film also includes original interviews with the three remaining members of Highsmith’s family who knew her (her nephew’s wife and their two adult children) and three of the author’s lovers (American lesbian pulp writer Marijane Meaker, German actor and costume designer Tabea Blumenschein, and French Boy Who Followed Ripley muse Monique Buffet), as well as extensive extracts from the author’s 56 diaries and notebooks, performed vocally by Game of Thrones actor (and Highsmith superfan) Gwendoline Christie. Vitija began research for the film in 2016 and commenced filming two years later; a documentary focusing on Highsmith’s love life that involved speaking to her loved ones needed to be done immediately, if ever at all, and three of the film’s six interview subjects have died since filming.

Initially drawn to Highsmith’s published work, it was only in reading the author’s unpublished self-writing (preserved in the Swiss Literary Archives in Bern) that the 49-year-old Swiss screenwriter and director, as she tells us, “fell in love with Patricia Highsmith herself.” The title of the film is earnest: Vitija’s documentary enters the world with some surprising, contemporary company. A thousand pages of Highsmith’s 8,000-page collection of diaries and notebooks, which the author kept since the tender age of 20, were published in late 2021 by Liveright Publishing just ahead of the documentary’s arrival. And in April 2022, Grace Ellis and Hannah Templer published Flung Out of Space, a graphic novel “inspired by the indecent adventures of Patricia Highsmith” that reimagines Highsmith’s personal life as she writes her 1952 novel The Price of Salt, taking cues from Joan Schenkar and Andrew Wilson’s respective biographies of Highsmith, as well as Meaker’s autobiographical account of her relationship with the author. After its Swiss premiere, Loving Highsmith played this summer at Docaviv (the Tel Aviv International Documentary Film Festival), the Sydney Film Festival, the Athens International Film Festival, and the Rio de Janeiro International Film Festival, as well as the Film Forum in New York, the Frameline San Francisco International LGBTQ+ Film Festival, and the Outfest Los Angeles LGBTQ+ Film Festival. The documentary is now available on DVD from Kino Lorber.

Loving Highsmith exists as a cinematic curio for those curious about the person behind the books behind the films. Across the documentary, Vitija adopts a familiar method, one made possible through the publication of Highsmith’s diaries: pairing fiction with nonfiction, reading one in light of the other. Vitija provides the cut of Carol that lives in so many imaginations: Highsmith’s own words about working in the doll section of a department store during the Christmas season and waiting on the most striking woman, blending into Christie reading from The Price of Salt, on top of Haynes’s sensuous footage of Therese and Carol’s meeting. The documentary then jumps ahead to a scene of Haynes’s Therese developing photos of Carol, but Therese the photographer is transmogrified into a writer, while on the soundtrack we hear Highsmith speaking about writing out in her notebook that night the whole story for what would become The Price of Salt. Later, the final scene of Haynes’s Carol, Highsmith’s notorious “happy ending,” is juxtaposed not with talk of young Highsmith’s stalking of the striking Mrs. E. R. Senn or Senn’s suicide within the year (relationship unkindled, inspiration unknown: see Schenkar) but with a later-in-life breakup between Highsmith and a married woman, whom she followed to the English countryside. Haynes’s tentative, dreamlike slow-motion shot/reverse shot grows bittersweet with our knowledge of Highsmith’s personal heartbreak. Following the cut to black hangs not the hope of possibility, a queer future unseen, but Highsmith’s words, delivered by Christie in voiceover: “Getting ready to sell the house in England. It is a negative thing. Perhaps like an abortion.”

Much has been made of the uniqueness of Salt’s ending in contrast to the lesbian pulps of its time, including those authored by Meaker under the name “Vin Packer,” and Vitija’s film is no exception. However, according to lesbian film scholar Patricia White, Haynes’s hard cut to black at the end of Carol seals the fantasy of desire, promising not together-forever but further pleasurable cycles of desire and loss, following, if ever so subtly revising, a long-standing melodramatic lesbian script. Vitija’s documentary, meanwhile, moves us through such lived cycles for Highsmith. And in equally lesbian fashion, the novelist’s late-in-life lover Monique Buffet narrates much of the story of the English lover as well as that of the end of Highsmith’s romance with Tabea Blumenschein, who came between the English lover and herself.

The Price of Salt (renamed Carol in 1990 when the novel was released under Highsmith’s name, rather than the pseudonymous Claire Morgan) has long been considered Highsmith’s most personal novel, and Vitija’s documentary largely bolsters the gendered logic that undergirds such claims: Patricia Highsmith was a lesbian. A lesbian is a woman who loves women. Therefore, Carol, the author’s only novel from the perspective of a woman and about women-loving women, is her most autobiographical work. At one point, Vitija asks Meaker, “Why do you think Pat always wrote books with male protagonists?” Meaker answers, “Because they sell best.”

Market considerations, coupled with patriarchy, are hard to dismiss. But Highsmith’s diaries evidence little disciplining, no anguish over wishing to write women characters. Elsewhere in the film, Vitija asks, “Why did Pat never publish a ‘girls’ book’ again?” Meaker answers, “The family. Certainly family. Certainly mother.” Meaker utters the last word with a vitriol that recalls Norman Bates in Psycho. But it is Highsmith who, in notebooks, interviews, and the afterword to the 1990 reissued Carol, tells us that she hated the publishing industry labeling her a “suspense” writer, as they did, or a “lesbian-book” writer, as she speculates they would have done had she published Carol under her own name. “Girls’ book” was the label Highsmith gave Carol in her notebooks (as well as a later attempt at a similar story), but there was more than a tinge of sardonic irony to it. As feminist cultural historian Victoria Hesford emphasizes, “Neither simply a ‘mystery writer’ nor a ‘woman writer,’ Highsmith and her work evaded categorization, in both form and content.”

Carol is not unlike Highsmith’s other novels in that there is something obsessively romantic in its characters’ drive to kill. Furthermore, while violently masculine, Highsmith novels work inasmuch as they not only construct our own complicity in the fictional murder or murders but also reveal our complicity within those systems of power that police and protect criminality. They align us with their particular protagonists and, eliciting curiosity if not necessarily identification, draw us deeper and deeper into the fray. Highsmith novels become about our desire — for things, for others. They become about our wish to control others, our yearning for respect, and our insecurities about why we may not get the respect we think we deserve. In a few harrowing cases, this materializes in violence against women. Anyone who has qualms about such, in making it to the novel’s end, must sit with what led them there. Was it Highsmith’s writing? Sure, of course. But wasn’t it also your desire, at the least your desire to know too? More often, Highsmith’s men are drawn to other men, and the violence thus befalls one ostensibly less distinguished in terms of power. And onscreen, in the case of Minghella’s film, this pull becomes as magnetic as that between Therese and Carol.

Vitija’s sampling of Haynes’s Carol is at the heart of this film devoted to Highsmith’s lesbian loves. But Minghella’s Ripley is not far behind, as Vitija in the second half of the film addresses Highsmith’s counterintuitive claim that Tom Ripley was her true surrogate. It would be easy to argue that male homosexuality as it appears in Highsmith’s fiction allowed the author to write the lesbian while also dodging spurious charges that writing the lesbian may have brought; the film hints as much through Meaker’s interviews. Ripley’s significance is also attributable to an understandable identification with the male as a “woman writer” in mid-century America, one not unaware of her internalized misogyny. But neither of these arguments fully explains the affective richness of Highsmith’s male/male stories of obsessive pursuit and murder, the erotic charge of which comes to the fore in Minghella’s treatment of the first Ripley novel. Vitija’s remixing of the Minghella film, alongside the testimony of Highsmith’s lovers, teases out — without spelling out — the writer’s interest in not only sexuality and cis genders but also masculinity and femininity as they play out and compound in men and women and others, whether or not they are coded or labeled as “gay” or “lesbian” or anything else.

¤

A sequence that falls almost halfway into Loving Highsmith suggests how Ripley and Highsmith (Tom and Pat, respectively) queerly share genders — by way of snails.

Let me back up.

One of Highsmith’s well-known quirks was her fascination with snails. In her biography of the author, Schenkar writes that Pat kept hundreds of snails as pets and, late in life, would tell dinner guests stories of sneaking the slimy creatures across the French border “under her breasts.” (This was likely just Highsmith being theatrical; usually, she used cottage cheese cartons.) In Vitija’s film, sensual black-and-white photographs of Highsmith with one and then two snails climbing her fingers are paired with an interview in which Buffet notes, “Ultimately, snails are hermaphrodites. Maybe that fascinated her too.” Buffet explains, “She liked people who were a bit half-and-half. If you take a closer look at Ripley, he’s not really that masculine. He has a feminine side too.”

With the ding of a lobby elevator, Vitija cuts from the snails to Damon’s Tom Ripley checking into a hotel under his own name and then another under Dickie Greenleaf’s, hair now swept back, glasses and corduroy jacket gone. Tom scratches out Dickie’s passport photo. “It’s her alter ego,” Buffet states, and horn-rimmed Tom unzips Dickie’s jewelry case. As Tom tries on Dickie’s watch while doing impressions of Marge and Dickie in the mirror, Christie delivers Highsmith’s thoughts on “the writer” as lacking a consistent personality; instead, “he is always part of his characters.” An alter ego is not exactly the same as an artist bringing their work with them as they socialize and interact with others. But if Highsmith is always a little Ripley, and Ripley aspires to both have and be a little Dickie, trying on his clothes and dancing in the mirror, could the queer desire driving the novel and its adaptation be in part a trans one? Released in 1999, the same year as Kimberly Peirce’s Boys Don’t Cry and the Wachowskis’ The Matrix, could Ripley offer another way of sensing transgender (to borrow Cáel M. Keegan’s term)?

In his review of Minghella’s film, Frank Rich writes that “[t]hose who wish to remake themselves in gender, age or biography, whether for fun, profit or criminality, need merely trot out a new screen name on AOL […] It’s into this fluid world that The Talented Mr. Ripley has been released.” Rich argues that “[w]hile Ripley has to laboriously scratch out a passport photo to trade in an identity, we can do it in a digital click.” Those who have in fact tried to “remake themselves in gender” and get a new government-issued ID know that it is not this simple. Judith Butler famously argued, at the start of the decade that brought us the Minghella film and the year that gave us the new book title “Carol by Patricia Highsmith,” that “gender is always a doing, though not a doing by a subject who might be said to preexist the deed.” Who does gender more performatively (in the Butlerian, not the colloquial, sense) than Damon’s Tom’s Dickie? Trans studies scholar Hil Malatino has recently claimed that “envy and ensuing emulation are part of how all gender is assumed.” For those who have spent years processing whether one was a man or how to become one, Malatino writes, envy is a reprieve, a fantasy space of what may still come to be.

In Damon’s Tom Ripley, then, we do not see the prehistory of our “quick and easy digital world” of identity (hardly). We see someone who dares to desire and dream, not unlike many of us, if most unusually willing to kill to get it. In Minghella’s cuts between Damon as Tom and Damon as Dickie, we get a decidedly analog fantasy of the “what if” or “if only.” And the film’s suspense, like the book’s before it, comes from not knowing whether Tom will be found out. But, as Highsmith says in an interview excerpted following Minghella’s footage of Tom murdering Dickie, “He’ll always get away with it.” It is no small thing that, since 1999, this trans fantasy of undetected becoming has played out time and again only after Dickie’s final bullying of Tom, a femininized parody of the envying man: “You give me the creeps! I can’t move without ‘Dickie, Dickie, Dickie,’ like a little girl all the time.” Dickie’s murder is horrifying, but, in a year with so much anti-trans and anti-gay violence, so is the threat of this taunt that precedes it.

¤

Yet, Vitija’s documentary never utters the word “transgender.” Joan Schenkar’s biography, which, following an account of what Schenkar calls “the gender wars [Highsmith] waged within herself and represented in her dress,” issues the 15-word stand-alone paragraph: “The term ‘transgender’ hadn’t yet been invented. If it had been, Pat wouldn’t have used it.”

Unlike others who have recently returned to the archives of “women writers” to make arguments for their transness, like Peyton Thomas’s Jo’s Boys: A Little Women Podcast on Louisa (or, as the author went by, “Lou”) May Alcott, I am disinterested in settling the matter of Highsmith’s gender once and for all. Trying to land on a label strikes me as awfully ironic, considering this author’s distaste for labels. That said, Schenkar’s doubly speculative dismissal strikes me as more than a little defensive. An appropriate response — for someone who, like Schenkar, has read Highsmith’s many dozen diary entries along the lines of “I am at once child and man, girl and woman. Sometimes a grandfather,” and, “I want to change my sex — is that possible?” — might be to quote Butler’s 1999 preface to the reissued Gender Trouble, where they queried, “Is the breakdown of gender binaries, for instance, so monstrous, so frightening, that it must be held to be definitionally impossible and heuristically precluded from any effort to think gender?”

Vitija gives her subject’s lovers the space to speak about such gender matters for themselves. Not too long before Buffet describes Highsmith’s love for hermaphroditic snails, Blumenschein talks about “KV,” or drag kings, and her own love of doing drag. Later, we learn that, in the 1970s, another of Blumenschein’s lovers, German filmmaker Ulrike Ottinger, was considering making a Ripley film of her own with Blumenschein in the leading role but instead made The Infatuation of the Blue Sailors (1975), in which, as Highsmith once wrote a friend, “everyone’s sex was reversed.” It was in that film that Highsmith fell in love, as she wrote in verse, “not with flesh and blood, / but with a picture: the sailor cap / The crazy mustache, the little bird / Perched on the girl-sailor’s [Blumenschein’s] right shoulder, / And the puzzled and somewhat serious eyes.” Later still, Vitija presents us with photos of Highsmith and Buffet in a garden, the latter in handsome suspenders and pants, as we hear her speak about how she inspired the character of the boy in The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980), the decidedly queerest Ripley novel, featuring a Ripley-investigating-while-in-girl-drag moment.

In Vitija’s film, years and fashions come and go, moving back and forth in time with little indication of season or decade, but Highsmith’s shoulder-length brown bobbed gestalt remains the same. Queerly fascinating for me, when it comes to Highsmith, is the fact that some of the most sensual images of her that we have — including one iconic nude, her hands bracing a door frame, chest confidently bare — were taken by her gay male lover, German photographer Rolf Tietgens. Reading Highsmith’s diaries reveals that the two had a passionate romance in the summer and fall of 1942, and they would return to one another periodically for years to come. In her August 13, 1942, diary entry, Highsmith recounts identifying one photo by Tietgens that she especially liked, to which he responded, “I knew you’d like that one. Because you look very boyish. You are a boy. You know.” After she speculates as to whether she could be in love with him, she writes, “[B]oth of us can excuse ourselves by saying it is not, of course, the opposite sex.”

In Vitija’s film, Tietgens’s nude photograph of Highsmith accompanies the sequence about Buffet and Highsmith getting together, roughly 30 years after the photo was taken. In fact, the only mention of Highsmith dating men appears early in a diary account of her teenage self being set up by her mother and finding kissing boys to be “like falling into a bucket of oysters,” an ironic repurposing of the slimy signifier of lesbian love. Elsewhere in her diaries, Highsmith describes it as “like kissing the side of a baked flounder.” Fishiness, indeed!

The graphic novel Flung Out of Space similarly shores up Highsmith’s sexuality by focusing on the period during which she went to therapy to be “cured” while it visualizes her lesbian gaze through lovingly fetishistic comic-book panels, even when she is literally in the arms of her most long-term boyfriend, Marc. And it’s not that, having read the diaries, Vitija’s or Ellis and Templer’s accounts ring untrue. Certainly refreshing about each is their writing of lesbian love as world-building, generative, not simply a reprieve from heteropatriarchy. But for me, Highsmith’s account of being with Tietgens in particular, coupled with his photographs and words, serves a similar function as Minghella’s Tom/Dickie/Tom montages, where the queer transmasculine desire both to have and to be commingle, sexily, fantastically, and do so very much alongside the lesbian.

Vitija’s use of Ottinger’s images invites us to look with Highsmith at young Tabea Blumenschein, much as her use of Minghella’s film invites us to look with Damon’s Tom at Law’s Dickie. In so doing, we are gifted queer moments that might be properly named “gay” or “lesbian” but which take those as capacious, arguably even overlapping, forms of naming. Highsmith’s diary-reading voiceover performed by Christie (the documentary’s own vocal doubling of loving/being) and which regards Blumenschein — “If I would touch you, maybe you would shatter / Or dissolve, like a dream one tries too hard to remember” — recalls the haunting stills of Tom staring lovingly at Dickie asleep on a train. On the soundtrack, Highsmith states, “Ripley’s sex life is very ambiguous. He’s rather shy and a little bit homosexual.” Tom removes his glasses and rests his head on Dickie’s shoulder, inhaling his scent. As soon as he does, a steward knocks on the train cabin’s window, announcing the upcoming stop, and Tom jerks his head back to his own headrest, his intimacy with Dickie, like Highsmith’s own with Blumenschein, dissolved like a dream. In its place, Vitija leaves an image of Tom and Dickie doubly doubled, captured in half-profile and reflected in the cabin window, four, rather than two, of them linked like homemade paper dolls.

In such moments of gender trouble, inconspicuously connected across Vitija’s film, this more complex, many-gendered (or perhaps much-gendered) understanding of Highsmith’s relationship to her protagonists comes into view, if soon slipping around a corner like a Highsmith character being pursued/in pursuit (also, in Highsmith, often both at the same time). Loving Highsmith is a film for those who love Highsmith, including those of younger generations, like myself, who came to the author’s work and life story by way of Minghella’s Ripley and Haynes’s Carol.

Just the other week, a transmasc drag king, a few years younger than me, shared a screenshot of Tom and Dickie in their Instagram story. Dickie has his arm around Tom’s shoulder, and Tom is looking at Dickie squarely, fingering a letter from Dickie’s dad, astonished at the violently gentle way Dickie is dumping him: “We’ve had a great run, though, haven’t we?” Over this image, Gray (who performs as Larry Styles) typed, “One of my favorite style inspos is Dickie Greenleaf … Like look at this suit [it’s purple] and the way he wears a hat.” When I messaged Gray about it, Gray wrote of Dickie, “Watching him provokes something in me — like, oh — could I also be a fancy boy?” There is no way that Highsmith, who passed away in 1995, could have anticipated such a world not only where her novel would be adapted yet again, and so sensually, but where the film is, like its peer The Matrix, meme-ified and repurposed 1,000 different ways. But for those of us intimately familiar with the gender trouble of loving Highsmith, it is no surprise. Vitija’s new documentary offers lesbians, trans fags, and queers of all stripes new fodder for our fantasies. The only suspense remaining is what loving Highsmith will lead to next.

¤

The author would like to thank Rachel Corbman, Brett Iarrobino, and Hugh Manon for their feedback on this essay and their encouragement.

¤

Rox Samer is the author of Lesbian Potentiality and Feminist Media in the 1970s (Duke UP, 2022) and, with Sonia Misra, the co-editor of Su Friedrich: Interviews (UP Mississippi, 2022). More about their research and creative work can be found at https://roxsamer.com.

LARB Contributor

Rox Samer is the author of Lesbian Potentiality and Feminist Media in the 1970s (Duke UP, 2022) and, with Sonia Misra, the co-editor of Su Friedrich: Interviews (UP Mississippi, 2022). More about their research and creative work can be found at https://roxsamer.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

What History’s “Bad Gays” Can Tell Us About the Queer Past and Present

Scott W. Stern explores the antiheroes of gay history in Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller’s “Bad Gays: A Homosexual History.”

The Haynes Code

Jean-Thomas Tremblay reviews a recent anthology about Todd Haynes as feminist-queer filmmaker.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!