What History’s “Bad Gays” Can Tell Us About the Queer Past and Present

Scott W. Stern explores the antiheroes of gay history in Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller’s “Bad Gays: A Homosexual History.”

By Scott W. SternJune 3, 2022

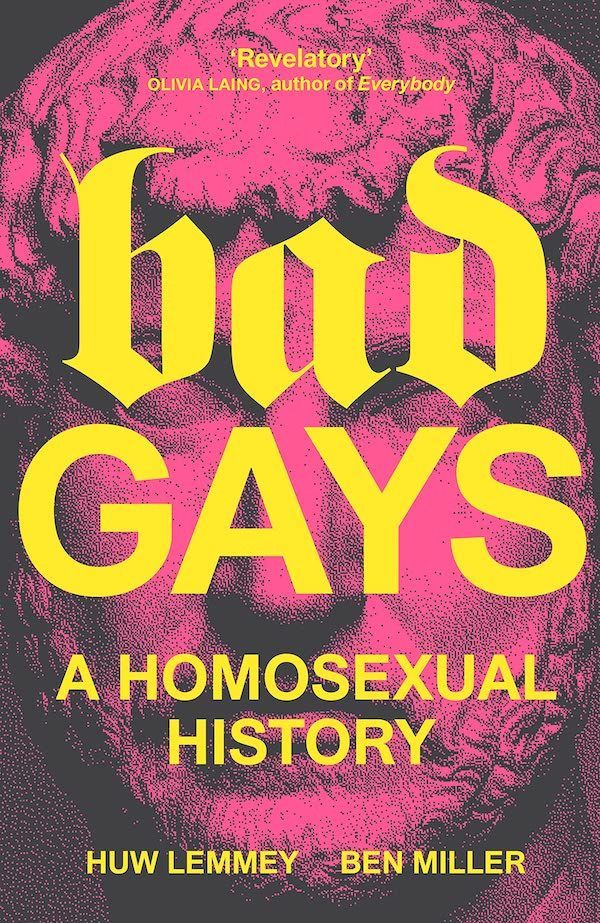

Bad Gays: A Homosexual History by Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller. Verso. 368 pages.

IF YOU HAPPEN to take a stroll down the main thoroughfare of Hillcrest — San Diego’s historically gay neighborhood, where I currently live — you will likely come across some of the strangest public art you’ll ever see. Block after block, banners adorned with the faces of queer celebrities flutter from atop street lights. Below the smiling faces, printed on garishly colored backgrounds, are captions that the youths would describe as, well, cringe. “Proud Like Chaz,” as in Bono. “Sharp Like Anderson,” Cooper, that is. “Witty Like Neil,” “Fierce Like Janet,” “Fiery Like Laverne,” “Fun like Lily” (whom the sign tells us “has been involved in” several “gay-friendly film productions”). “Glam Like Liz” — Taylor, because I guess allies are welcome too. “Fab Like Elton,” on a plane of cheery purple. “Wild Like Gaga,” alongside a wildly outdated photograph of the singer, songwriter, and actress “known for her work related to LGBT rights.”

You might wonder where these posters come from, and what exactly they’re for. The answer, apparently, is contained in the logo at their base. “Fabulous Hillcrest,” it reads in old-timey font, “Dine * Shop * Play.” It seems that some collection of local business owners has sprung for these posters, seeking to capitalize on the neighborhood’s gay history, draw in an affluent queer clientele, and get them to spend, dwell, and have a little fun. Merchants insinuating cruising and casual sex — how far we’ve come.

This convergence of queerness and capitalism, accompanied by more than a whiff of desperation, might also lead one to notice a striking juxtaposition. The celebrities in the posters are grinning down not just at well-heeled gays on their way to Breakfast Bitch, Out of the Closet, and The Rail, but also at a significant unhoused population, doing their best to avoid the violence of the state. Like many California cities, San Diego is home to a great number of people lacking in stable shelter, and Hillcrest’s business district is one place where the unhoused are most visible. Alongside so many homeless people — who, according to a study from UCLA’s Williams Institute, among others, are disproportionately queer — the presence of the rich and famous (and fierce, fab, glam, etc.) makes for an especially jarring contrast. In the face of such an unconscionable level of poverty and suffering, the use of resources to memorialize the most privileged among us — and the positioning of these posters as themselves some sort of social good — is troubling and revealing.

History has long been central to the fight for gay rights. In the early days of the liberatory movements that exploded after Stonewall — as queer people started to come out, to overcome shame, to fight for civil rights, to even fight the cops — many began looking back through history, seeking to find examples that proved that we have always been here. They seized on figures ranging from Oscar Wilde to Sappho, Abraham Lincoln to Leonardo da Vinci, to show that queerness was not some novel thing, that many of history’s heroes and innovators and pioneers had been queer, that they had a past of which they could be proud.

“This was important work,” acknowledge Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller in their provocative new book, Bad Gays: A Homosexual History, yet it was also, inevitably, reductive. Indeed, accepting queer people as full human beings also means accepting that many are and were flawed. Queers fought the Nazis, but what about the queers who were Nazis? Understandably, queer activists, ordinary queer people, and the capitalists of Hillcrest may not wish to lift up the queer frauds, queer criminals, queer murderers. “But is it not time we also look at those whom the early gay rights pioneers were less keen to claim as family, as one of us?” Lemmey and Miller ask. The “bad gays,” too, have always been here. And if the price of “acceptance” is a kind of social sainthood, an anodyne and sanitized and unthreatening model minority, perhaps that price has become too high to pay.

To be sure, legions of homophobes have not hesitated to conflate all queer people with pedophiles or cannibals, with John Wayne Gacy and Jeffrey Dahmer and the like. But few people who are not expressly bigoted have systematically considered history’s queer villains and their enduring significance.

Lemmey and Miller — both, like this reviewer, gay men — have set out to remedy this absence. To this end, they have written a book consisting of 14 chapters, each one profiling a “bad gay” or group of “bad gays,” from the Emperor Hadrian to J. Edgar Hoover and Roy Cohn, from King James of England to the Japanese writer, bodybuilder, and militia leader Yukio Mishima. The book covers individuals from ancient times as well as the recent past, including both the (in)famous and the unknown, although (for reasons that become plain) the focus remains on powerful white men in the Global North.

“Bad gays,” the authors write in the book’s introduction, are “the gay people in history who do not flatter us, and whom we cannot make into heroes: the liars, the powerful, the criminal, and the successful.” This is a broad definition, perhaps too broad, and a necessarily subjective one, but a few pages later the authors offer a helpful clarification: many queers on the “bad” spectrum — encompassing everything from fascists to assimilationist gays who would leave their marginalized queer brethren behind as they easily climb the ladders of social and economic capital — “have wanted to position themselves as heirs to a secret or magical kingdom, as the inheritors of a chain of heroes. The process of making the movement and the identity has often involved reifying, recreating, and worshipping power and evil in their most brute forms.” Their book, then, is about the worst gays throughout history, but also about the worst uses of gay history, and the myriad ways that an uncritical celebration of “good” gays and “good” gayness can cause harm.

Only by deconstructing the romanticized past, the authors conclude, can queer people in the present recognize the profound limitations baked into mainstream gay politics. Only then can we move beyond those limitations and toward the solidarity that makes liberation for all people possible.

There remains, of course, the sticky matter of whether many of the powerful and evil and complicated individuals profiled in Bad Gays were, in any coherent sense, actually gay. Although it is clear that many had what we would today characterize as queer sex or queer intimate relationships, some did so long before the idea of a stable sexual identity existed. The inadequacy of the surviving historical record likewise makes it difficult to determine how, exactly, many of them would have identified (or, for that matter, the details of their sex lives). Yet as the authors point out, decades ago the term “gay” included anyone who lived beyond the heterosexual and cissexist norms of their society. It is, to some extent, still a useful blanket term. Lemmey and Miller have decided to use the term “gay” to put “today’s homosexuality under a microscope,” to determine “why it is troubled and incomplete, and why it failed to live up to its utopian promises of liberation.”

Bad Gays is an estimable project, with a great title and a great premise and a highly readable, often rollicking, occasionally heartbreaking narrative. That, in some ways, it falls short of proving its broad thesis hardly matters in light of its many triumphs, perhaps most of all its relentless commitment to cutting through complacent liberal bromides about the arc of queer history. To ignore history’s “bad gays” risks doing as the Hillcrest business owners have done — celebrating an idealized vision of the queer past while ignoring a desperate queer present.

¤

For more than three years, Lemmey — a British novelist, artist, and critic living in Barcelona — and Miller — an American writer, researcher, and academic living in Berlin — have run a popular podcast called Bad Gays, and it is from the research for that project that they have produced their new book of the same name.

I first stumbled across Bad Gays in the dark days of late 2020, when my husband sent me a link to “Tossed Salads and Scrambled Eggs,” a delightful, erudite (and, sadly, now largely inactive) newsletter in which Lemmey was undertaking deep, deep dives into each episode of the sitcom Frasier, drawing on literature, theory, psychology, and much else. I tore through the newsletter’s archive and, after quickly exhausting its offerings, went looking for more of Lemmey’s work.

Bad Gays is, as its log line attests, “a podcast about evil and complicated queers in history.” Over dozens of episodes, its hosts have profiled a true murderer’s row of “bad gays” — from Andy Warhol to Andrew Sullivan, from Gertrude Stein to Pete Buttigieg — although Lemmey and Miller are judicious in assessing, at the end of each episode, whether their subject du jour was truly “bad” or truly “gay,” or whether (as is often the case) reality is much more complicated.

Appropriately enough, the very first episode was an excavation of “the world’s first openly gay politician,” Nazi militia commander Ernst Röhm — a very bad gay if ever there was one. From there, the series jumps across time periods, although it has an understandable tendency to return to relatively recent history.

Bad Gays is one of the rare podcasts that’s only gotten better over time. Its early episodes were interesting, if occasionally wooden, with Lemmey or Miller reading potted biographies to the other. As the podcast went on, though, the hosts began inviting on expert guests, providing more panoramic context, and taking on more and more ambitious subjects. Standout recent episodes include pirate queen Anne Bonny, which allowed its hosts to explore the queer history of piracy; opera queen Franco Zeffirelli, in which Miller brilliantly explicated the complex queerness of 20th-century opera; bank robber John Wojtowicz, which spun out into a stimulating survey of 1970s gay/trans politics; and a satisfyingly blistering two-part exposé of Cressida Dick, the first woman and first out queer person to serve as head of London’s police force.

Lemmey and Miller are able hosts with distinctive narrative voices (voices that a loyal listener will have no trouble recognizing across the various chapters of the book Bad Gays). And their different national backgrounds allow them to choose subjects from both sides of the Atlantic. Yet their podcast’s greatest achievement — and one shared by the eponymous book — is its unembarrassed scholarliness. Lemmey and Miller are commendably upfront about the sources of their material, often discussing the benefits or drawbacks of this or that biographical tome. Many podcasts provide their sources in the show notes, but Lemmey and Miller discuss them in the body of each episode, laying bare the scholarly process and revealing that history is not some neutral recitation of facts but a series of arguments.

¤

The principal way that Bad Gays departs from its podcast predecessor is its own sustained historical argument. Almost every subject of the book was previously profiled in the podcast, but Lemmey and Miller have now turned to many of the figures’ roles in the construction of gay history — and, thus, gay identity.

Their first chapter features the Emperor Hadrian and includes a good deal of information about the sex lives of ancient Greeks and Romans. When, in the Victorian Era, powerful European men began looking for “historical examples of their own same-sex desires,” they turned to the worlds of the Greeks and Romans, squinting to see “men who loved other men without shame, and who weren’t regarded by their peers as aberrant, diseased, and disgusting.” More recent examinations have shown that the truth of the matter was much thornier, Lemmey and Miller note. In particular, Hadrian’s “obsessive love for a much younger man” (reflecting the ancient idealization of pederasty) greatly “complicates the idea of an unchanging thread of homosexuality that passes through history […] of same-sex relationships that looked the same and felt the same.”

Nonetheless, the story of Hadrian also reveals the importance that power and wealth had in the story that gay men, especially, began to tell themselves about their past. A story that, not for nothing, ignored the violence of Hadrian’s rule, as well as the criticism he endured in his own time for having sex not merely with younger men but with men his own age too.

From Hadrian, Lemmey and Miller turn to the Florentine writer Pietro Aretino, a Renaissance-era “sodomite who so revelled in sin that his very name became synonymous with good fucking.” His wildly popular homoerotic prose, soon translated into English, was banned by the Catholic Church and may well have influenced Shakespeare; his queer texts were condemned after his death but, ironically, ensured his work’s longevity, providing a licentious model for prudish Victorians to define morality against. He also exemplifies a moment in Italian history in which sodomy transformed from a sin into a crime yet remained (its practitioners encouraged by a rediscovery of ancient queer cultures) “part of the functioning social system.”

As the centuries passed, the ancient Greeks and Romans were not the only cultures to which contemporary queers and questioners looked for models. Frederick the Great, 18th-century king of Prussia and the subject of the book’s fourth chapter, was celebrated as a hypermasculine model of male gayness by much of the early 20th-century German homosexual movement. Once again, this wholly ignored the difficulty of categorizing Frederick’s apparently “gay” relationships, the uniquely Prussian context for those relationships (which valorized “‘sensitive’ traits that later generations would come to view as ‘effeminate’”), as well as the violence and nationalism inherent in Frederick’s monarchic position (Hitler was a huge fan).

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, psychiatrists and sexologists — “newly empowered with the method and the mission to peer into the souls of the masses and try to make them better and more productive workers,” as Lemmey and Miller dryly note — began looking to history to construct “a homosexual identity and subculture.” Queer sex was no longer just what you did in private (or, occasionally, in public); it was becoming part of a fixed, stable identity, with queers themselves part of an identifiable group.

In the late 1860s, a limited-run German-language pamphlet coined the word “homosexual,” which a generation of “sexologists” soon seized upon, advancing startling (and, to modern eyes, often offensive, often bizarre) assertions about sexual variance and deviance. This research, as well as romanticized depictions of a classical queer past, influenced those that constructed a remarkably, albeit tenuously, liberated space within Weimar Germany. At the same time, though, English society was ramping up its anti-sodomy laws, criminalizing anal sex regardless of gender, as well as “everything that manifested desire between men,” and importing this repression all across its vast empire. A series of sodomy trials — including one involving Jack Saul, an Irish immigrant, sex worker, and subject of the book’s fifth chapter — awakened much of the public to the menace of gay sex, while, conversely, providing a model (in Oscar Wilde) for future gay men to idealize.

Many sexologists, as well as powerful queer men, began turning to the empire’s holdings to try to understand their own urges. The diplomats Roger Casement and T. E. Lawrence (“of Arabia”), both subjects of chapters in Bad Gays, exemplify the repression inherent in colonialism (even when the colonial officers themselves mean well). Casement and Lawrence fought heroically against the cruelties of empire even as both denigrated and fetishized Black and brown men, contributing to broader modes of marginalization. Meanwhile, Casement’s and Lawrence’s diplomatic colleagues justified the violence of colonialism by claiming that they simply had to stop dark-skinned men from committing acts of sexual immorality; these colonial administrators then exported the tactics and technologies of repression, introduced in the colonies, back to the Global North. A generation later, Margaret Mead — subject of the book’s ninth chapter — and other anthropologists (many of them “pioneering women, queers, Jews, and people of colour,” the authors note) would use exoticized portrayals of people in the Global South to convince the Global North that queerness was natural, even universal. This work, while influencing almost every progressive social movement in the Global North, nonetheless justified condescension and bigotry and even violence enacted against those living elsewhere.

The decades that followed continued the complex and unsatisfying narrative of progress and backlash, with fleeting moments of solidarity and crushing unintended consequences. “Certain narratives within liberal gay circles like to paint the gay rights enjoyed in some Western countries not just as the inevitable product of the Western nation-state, a slow forward march towards rights and justice, but also as permanent, intractable, the end-point of progress,” Lemmey and Miller write. “But the history of bad gays complicates that; our history is full of failed attempts at liberation, at new boundaries rolled back in public book burnings, of the ever-present threat of state suppression and social stigma.”

In the United States, the homophile movement began bubbling up in the early 1950s, setting the stage for the explosion of gay lib in the ’60s and ’70s. At the same, though, federal administrators — led by “bad gays” J. Edgar Hoover and Roy Cohn — made life miserable for thousands of queers, ironically using tactics like rumor, gossip, and guilt by association that would eventually lead to their own respective outings. Elite white queers — including Hoover, Cohn, and the Nazi-sympathetic modernist architect Philip Johnson, subject of the book’s 12th chapter — were mostly able to avoid such horrifying consequences, with Johnson ultimately capitalizing on the progress made by more marginalized queers after Stonewall to enjoy an increasingly out lifestyle in his later decades.

The AIDS epidemic led to a short-lived coalition between elite white gays and poorer queers of color, but the advent of effective medications in the mid-1990s mostly destroyed this seeming solidarity, as the most prominent gays, lesbians, and queer organizations turned toward an integrationist politics focused on enabling access to respectability and its attendant power, security and generational wealth. While gay liberationists had fought against the draft and inveighed against the misogyny of marriage, gay rights groups fought for the right to marry and to fight in the military. A number of gay men — including Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn, subject of the book’s last chapter — even became avatars of far-right, fascist-friendly politics, using their gayness as a shield against criticism as they promoted the war machine and accused migrants, especially Muslims, of intolerance. “I don’t hate Arabs,” Fortuyn — promoter of avowedly Islamophobic policies — quipped to the press. “I even sleep with them.”

¤

“The history of homosexuality is a long history of failure,” Lemmey and Miller write in the book’s conclusion. While some queers — mostly white, gay, cisgender men living in the Global North — have won rights and even power, more marginalized queers — immigrants, people of color, transgender and nonbinary people, intersex people, those in the Global South, above all the poor — have largely been excluded from the fruits of the fight for “gay rights.” Due, in part, to the foundational premise that equal rights for queer people must depend on our status as “good gays” — as loyal political subjects of a capitalist, heteropatriarchal, white-supremacist, settler-colonial state — the gays with power have almost invariably let down those with less economic, cultural, or political capital. “Maybe,” the authors muse, “it is time that homosexuality itself dies, that we find new and more functional and more appropriate configurations for our politics and desires.”

It is an arresting thesis, especially as it implicitly takes to task many pioneering 20th-century queer historians who scoured the archive for traces of an identifiable minoritarian group that persisted across time and space. From a distance of decades, it is perhaps too easy to dismiss the importance of that work in giving lonely, scared people — coming of age without many, if any, role models — a sense of themselves. Yet in their herculean efforts to construct such “usable” histories, these historians — and the activists who seized upon their work — may have sacrificed nuance, complexity, and context.

Even further, their historical claims “were perfectly fitted to advancing what we might call the mainline liberal position for gay acceptance in the later twentieth century,” as the historian Jules Joanne Gleeson argued in a recent essay. Accept us because we are just like you, went the message. Give us rights because all we want, all “we” have ever wanted — in every time and place in which we have ever lived — is tolerance and the chance to lead “normal” lives. To more radical queers, Gleeson noted, this work too often looked like “urbane wealthy homosexual guys turning their gaze across historical sources to find experiences that match their own.”

Because Bad Gays (like its podcast forebear) is far more concerned with biography than with consistent argumentation, its assertion that homosexuality itself be jettisoned in favor of “something else, something better, instead,” mostly stops at the level of provocative suggestion. The book is more a series of essays than a laser-focused monograph, and as a result the reader is largely left wondering what this “something else, something better” might be. In the book’s conclusion, the authors write movingly, albeit quite briefly, about “alliance and solidarity that offer us alternative futures, should we wish to dream them forward,” from the antiracist, pro-queer union organizing of 1930s California, to the multiracial, working-class street kids, drag queens, trans women, and sex workers that rioted against state violence across 20th-century America, to the lesbians and gays that supported striking miners in Thatcher’s Britain. Yet this is just a glimpse of a better world.

Nonetheless, as a bold and eminently readable counterhistory of homosexuality, Bad Gays is a triumph. To their credit, Lemmey and Miller have not lost the podcaster’s informality. One early sentence begins: “The twink theft of the perpetually horny Hadrian did not go unanswered…” Meanwhile, two different subjects (Casement and Cohn) are each labeled “a size queen.”

Even more significantly, Lemmey and Miller have brilliantly revealed the human construction of queer history. The historical narratives that we have received, far from an impersonal list of names and dates and fights, were chosen by individuals with agendas, flaws, and imperfect sources. Indeed, the authors note, only after J. Edgar Hoover’s death did an unlikely source — his friend Ethel Merman — publicly confirm the rumors of his queerness, leading to an outpouring of more colorful stories of the FBI director cavorting at orgies, in full drag. Only in the 1990s did an unlikely find in the garbage room of a building in Vancouver provide scholars with the records to adequately reconstruct Weimar queer liberationist Magnus Hirschfeld’s extraordinary activism. Only in 2018 did a biographer reveal the extent of Philip Johnson’s fascist collaboration.

In providing a pantheon of antiheroes, in reveling in complexity and contradiction, and in doing so for a popular audience, Lemmey and Miller have constructed their own narrative of queer history, one in which the “bad gays” take center stage. Their construction is, like all histories, selective, but it is a fresh and fascinating one at that.

¤

LARB Contributor

Scott W. Stern is a lawyer and historian, originally from Pittsburgh. He is the author of The Trials of Nina McCall: Sex, Surveillance, and the Decades-Long Government Plan to Imprison "Promiscuous" Women (2018). His writing has also appeared in the New Republic, Washington Post, Time Magazine, Teen Vogue, Boston Review, and Lapham's Quarterly, as well as half a dozen scholarly journals.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Sex Work as (Anti)Work: On Heather Berg’s “Porn Work”

Scott Stern reviews Heather Berg’s “Porn Work,” a new study that explores how labor functions — or doesn’t — within the adult film industry.

Is That All There Is?: Queer Culture and Politics on the 50th Anniversary of Stonewall

Much has changed in the 50 years since the flashpoint of the modern LGBTQ movement, but there is still much more to do.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!