No Childhood to Lose

Jan Cherubin reviews a debut novel about the legacies of childhood sexual abuse.

By Jan CherubinMarch 12, 2020

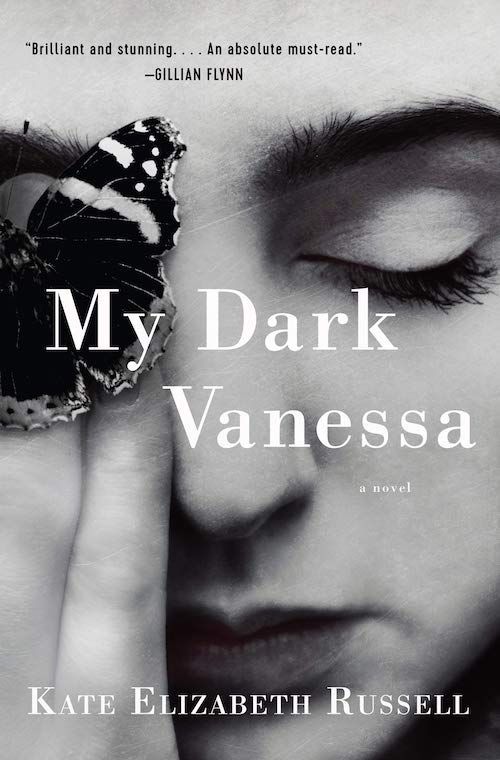

My Dark Vanessa by Kate Elizabeth Russell. William Morrow. 384 pages.

KATE ELIZABETH RUSSELL’S deeply affecting first novel, My Dark Vanessa, is a vivid account of the harm too often done to girls by men. Russell’s story alternates between 2017, when her eponymous protagonist is 32, and the year 2000, a more innocent time, when Vanessa, 15, is molested by her English teacher.

Vanessa narrates both periods in the present tense, providing an immediacy of feeling but little opportunity for reflection. This is intentional, of course. Russell won’t have the older Vanessa condescend to her younger self, nor will she obscure her innocence with hindsight. The writer demands that the reader witness the molestation as it is happening, and the story is stripped of either judgment or nostalgia.

At 32, Vanessa is a depressed, alienated underachiever living in a messy room in a shabby apartment in Portland, Maine, circumstances that are the consequence of her abuse. Once a promising writer, she now has a dead-end job as a hotel concierge. The novel opens with Vanessa checking the world’s reaction to a Facebook post by another student at the boarding school she attended. The post is attracting a lot of attention: “So far, 224 shares and 875 likes.” The narrative then jumps back in time. At 15, Vanessa is friendless and vulnerable — a scholarship student at the snobbish Browick boarding school and the object of desire for her charismatic, fortysomething American lit teacher, Jacob Strane.

How easy it is for Strane to groom his pet! He praises her writing and lures her into bed with lines from Nabokov and Sylvia Plath. Vanessa is grateful for her teacher’s attention, tolerates his ministrations, and is fiercely loyal. Not so his next victim, Taylor Birch, a few years behind Vanessa at Browick, who will later be the author of the explosive Facebook post. In 2017, emboldened by the #MeToo movement, Taylor seeks to out Strane as a pedophile, the internet permitting the sort of public statement that was unavailable to her as a schoolgirl. Taylor reaches out and tries to enlist Vanessa to bolster her accusations. Vanessa was notorious back in the day for lying to protect Strane’s job; she ended up taking the fall for him and getting kicked out of Browick. But Vanessa is not interested in joining Taylor in outing Strane. She’s still intermittently involved with the man, still loyal, still convinced their love affair is equitable and unique.

Vanessa’s isolation is striking. She and Strane exist with little context: neither seems to have had a childhood. Vanessa has scant support, in the form of friends or family, at either age 15 or 30. Granted, the abuse happens away from home at boarding school, giving some cover to her oblivious parents, but the failures of her family are ultimately as stark as the winter woods surrounding their house. Over the phone, and during visits home from school, her mother dispenses theoretical advice but is uninterested in Vanessa’s reality. “The secret to a happy life is not to let yourself be dragged down by negativity,” her mother advises. In Vanessa’s unspoken response, Russell captures the melancholy of certain sensitive adolescents whose identity seems to hinge on the depth of their emotion: “[My mother] doesn’t understand how satisfying sadness can be.”

Russell transforms emotion into words with remarkable precision. She perfectly describes the patronizing expression on Strane’s face as he admires his young student. “Mr. Strane smiles over his shoulder in a way that is both kind and condescending.” “He looks amused, like he thinks my frustration is cute.” “[He] makes sex feel like some sort of game that only he’s allowed to play.” Vanessa is momentarily annoyed by these reminders that her role in the world is small, and then feels grateful to loom so large in her teacher’s eyes.

In the interest of full disclosure, I, too, was abused at the same age (though in a different era) by an English teacher, and have written about it, although this disclosure hardly seems necessary. At this point, it’s like saying I, too, was a girl. I can vouch at least for the authenticity and heartbreaking irony of Vanessa’s thought process: “I am special, I am special, I am special.”

The sex scenes in My Dark Vanessa are erotic, but they succeed as well in magnifying the void between the two lovers. His need is ravenous, while her desire to please is barely necessary. “First I lift my face so my mouth almost touches his neck and I feel him swallow once, twice. It’s how he swallows — like he’s pushing something down within him — that gives me the courage to press my lips against his skin.”

Decades later, Vanessa remains stuck in the past, unable to escape the grip of what she doesn’t even recognize as trauma. She takes a cigarette break at work in the alley behind the hotel, where she encounters some teenagers. “I wonder what those girls saw when they looked at me […] if they dared to ask me for a cigarette because they could tell that, despite my age, really I’m one of them.” Her past is still her present, another reason for the present tense.

My Dark Vanessa received some pre-publication buzz after a seven-figure sale and a movie deal banking on the currency of the #MeToo moment, not to mention the potential exploitation of a titillating subject. The novel itself seems quieter. In a note in the front of the book, Russell stresses this is a work of fiction, while also revealing that some details of the story are based on her personal experience. She didn’t rip it from the headlines, but from a more painful place. The choice of the present tense, though, is undeniably cinematic — it’s a fast read. We want to know what happens — if Strane is ever held accountable. The novel has the confessional tone of a diary, or perhaps the novel itself is the metafictional blog Vanessa is writing.

What’s missing, without a reflective voice or the narrative authority of the past tense, is “emotion recollected in tranquility,” the old Wordsworthian definition of poetry. There is no tranquility for this narrator. Russell describes none of the idylls of a childhood Vanessa has presumably lost and never uses the heightened language of nostalgia. The omission of childhood memories isn’t addressed until the end of the book, when Vanessa’s therapist asks if she remembers herself at five. “I don’t think I remember anything about myself that happened before him,” she says.

Vanessa reads and rereads the copies of Lolita and Pale Fire that Strane gives her, but Russell’s story is no tribute to Nabokov or his exquisite writing. It’s more of a rebuke. She doesn’t even try to seduce the reader with beautiful sentences. She dedicates the novel to “the real-life Dolores Hazes and Vanessa Wyes whose stories have not yet been heard, believed, or understood.” The tone of the novel is not didactic, but I don’t think many readers will come away from My Dark Vanessa without a sense of moral indignation.

While Russell is a sure-footed writer with keen powers of description (some of the best sequences detail Vanessa’s job as a file clerk and have nothing to do with sex or obsession), we are not treated to the transcendence that comes when experience is fully transformed into art. There is no childhood to lose because, as noted, there is no childhood described. Instead, we experience the loss as Vanessa does, without the bittersweetness of memory — a loss that is real and complete.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jan Cherubin is a writer, editor, and standup comedian. Her first novel, The Orphan’s Daughter, will be published in June 2020.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Auspicious Conflagrations: The Heat of Women’s Anger

Bean Gilsdorf joins the chorus of women speaking about their anger, so that they can do something about it.

States of Desire: On Lisa Taddeo’s “Three Women”

Helena Duncan immerses herself in “Three Women” by Lisa Taddeo, a report on the state of women’s sexual desire in America.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!