Multiple Exposures: On “Double Vision: The Photography of George Rodriguez”

Geoff Nicholson focuses on “Double Vision: The Photography of George Rodriguez,” edited and introduced by Josh Kun.

By Geoff NicholsonMay 27, 2018

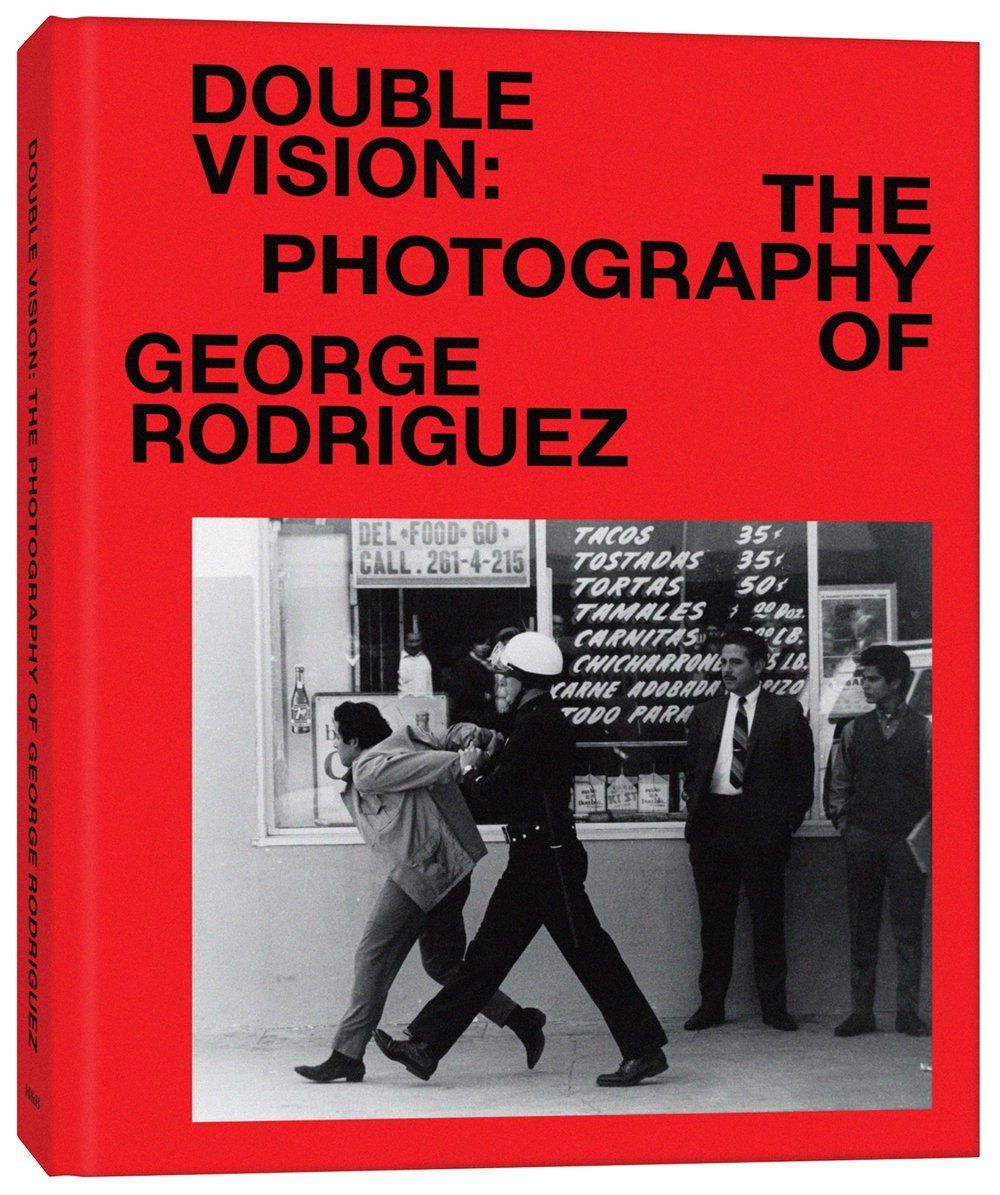

Double Vision by George Rodriguez and Josh Kun. Hat & Beard Press. 192 pages.

WHEN I FIRST started living in Los Angeles, I met a wise man, in fact a recent arrival from New York, who said to me, “In this town, you can forget about that ‘six degrees of separation’ stuff. Here, it’s more like two or three degrees.”

I’ve come to understand his point. The guy from AAA who came to start my car had a lot of stories about working on the old Jeep belonging to Barry White’s widow. When one of my ankles went bad, I found myself sitting in a doctor’s waiting room with Lou Ferrigno (though he didn’t wait nearly as long as I did). For that matter, I once sat at the same lunch table as Werner Herzog, who told me he thought John Major was a great British prime minister. I thought it best not to argue about that.

There are, no doubt, a lot of questions here concerning the nature of separation and the nature of connection. Herzog and I will not be calling each other to organize a night out bowling. But even so, Los Angeles does offer these brief, unlikely, and generally positive interactions across divides of class, race, and wealth. Of course the divides remain in place, but at least we see that we’re not living in completely separate universes.

And when it comes to degrees of separation, if you happen to know the photographer George Rodriguez (I, alas, don’t), it seems you’re well on the way to connecting with pretty much everybody in the city. In a career spanning at least 50 years, his photographic subjects have included Marilyn Monroe and Cesar Chávez, Rock Hudson and Frank Zappa, Dolores Huerta and Brooke Shields, Anthony Quinn and Omar Sharif, Edward James Olmos and Sugar Ray Robinson, to name but a few.

Even so, there are some surprises, some unexpected juxtapositions in the photographs. Is that Magic Johnson hanging out with the Dodgers while wearing a “Certified Bikini Inspector” T-shirt? Afraid so. And okay, we know that Ronald Reagan was a Hollywood guy, so it’s no big surprise that he’s at some L.A. dinner with showbiz folk, but it’s still amazing to see him and Nancy at the same table as George Burns, while Sonny Bono looks on from a less prestigious spot behind them. Judging by their faces, they’re all having a thoroughly miserable time.

Another example: It seems all too predictable that Jesse Jackson would be at a press conference during the United Farm Workers’ grape strike and boycott, and we know that Martin Sheen embraced his Hispanic roots and had a connection with Chávez, so yes, he, too, gets a place at the table, but that guy on the far right who looks like Robert Blake … Yep, that’s Robert Blake.

The fact that most of the Chávez pictures were taken in Delano, up in Kern County, and that one or two of the others were shot in Tijuana and Louisiana slightly spoils my L.A. connectedness thesis, but Rodriguez is a Los Angeles guy through and through. He was born in 1937 to a Mexican father and a Mexican-American mother. The family business was a shoe repair shop in downtown, and he went to Fremont High School in South Los Angeles, a place known at the time as the “doo-wop high school” — The Penguins and The Jaguars were alumni, and quite a few other bands too. As someone who grew up in England with an unlikely taste for doo-wop, I’m as amazed by this as if he’d been educated at Hogwarts. At Fremont, he learned to take photographs on a four-inch-by-five-inch Anniversary Speed Graphic camera, and his jobs after graduation included working in a photo lab and as a photographer on a luxury liner. His first “Hollywood” employment was as an assistant to Sid Avery, who famously shot celebrities in their “private moments” for The Saturday Evening Post.

So the professional “glamour” aspect of his work was there early on, but at the same time, initially for his own benefit, he also photographed considerably less glamorous scenes of Chicano life. Josh Kun’s introduction to Double Vision: The Photography Of George Rodriguez tells the story, from 1968, of Rodriguez running the photo lab at Columbia Pictures and, on his lunch breaks, driving down to East Los Angeles to photograph the walkouts and blowouts — student demonstrations against educational inequality — which Kun calls “the first major public actions of the Chicano movement.”

Rodriguez was also on the spot to photograph a requiem procession for Robert Kennedy in East Los Angeles, the Chicano Moratorium march, a neo-Nazi demonstration against Hubert Humphrey outside the Palladium, and the aftermath of the Rodney King riots. He was also there for the Sunset Strip riots, but they didn’t impress him much. “It wasn’t really a riot,” he says. “They were just stopping traffic and acting wild.”

At other times on the Strip, on non-riot nights, he photographed Jimi Hendrix, The Doors, and Jackie Wilson at the Whisky a Go Go. He photographed B. B. King in Long Beach, Arthur Lee in Northridge, Diana Ross at the Forum. He shot album covers for Van Morrison, Albert Collins, and Booker T. & the M.G.’s. He even had a spell working for the Laufer company, shooting covers for magazines such as Yo!, Soul Illustrated, and Tiger Beat. Cover models included MC Hammer, The Jackson 5, and Shaun Cassidy.

It’s a testament to Rodriguez’s skills, and perhaps his affability, that he was welcomed by so many different people into so many different worlds. Being likable isn’t the first requirement of a photographer but it seldom does any harm, and if you’re getting up close to photograph Frank Sinatra or Ice Cube, you really don’t want to piss them off. Perhaps he was simply benign. Certainly there’s no obvious viciousness in the photographs.

So yes, Rodriguez’s work as a whole isn’t exactly unified, but that’s okay, and it’s what comes inevitably from having the kind of patchwork career experienced by most freelancers. You go where the work is and you can’t afford to be too choosy, although that doesn’t mean you abandon your pride. Again in the introduction, Rodriguez tells the story of shooting in the Laufer studio: “[A] writer asked an actor what he did before acting. He said, ‘I worked in a factory and they had me back there with all the Mexicans,’ I just stopped taking pictures and walked out the door.”

In a note at the end of Double Vision, Rodriguez says, “Originally my idea for this book was to document the Chicano, Mexican-American experience,” and he had to be persuaded by friends and colleagues to include the other work. His original concept would have made a perfectly good book, and that subject matter is thoroughly represented in the current volume, but it seems to me this book is more interesting for taking a wider view of the world, for demonstrating and connecting the various degrees of separation. This breadth also rather undercuts the title: these are more like multiple exposures, layered superimpositions.

Which leads me to argue, amicably enough, with something Josh Kun writes in his introduction. He argues,

We have little room for the double-exposed, for the double lifers, and the cultural two-timers. We like identities to fit neatly into single categories, and we like social experiences to line up with and mirror those single categories without ever mixing within the frame or spilling out of it.

I’m not sure who the “we” is in that passage, but in contemporary photography that notion strikes me as simply untrue. Catherine Opie, to take a local example, is as known for her photographs of lesbian life as she is for photographs of mini-malls as she is for documenting the Obama inauguration, and none of it feels like a contradiction.

In the age of Instagram, things are changing all the time, but above all, for better or worse, the changes seem to involve a blurring of hierarchies, where a picture of a passionate political rally is given the same status as a photograph of a grilled cheese sandwich. But long before Instagram, Mapplethorpe could photograph hardcore gay S-and-M, then do a portrait of Susan Sarandon with her child, and then photograph exquisite floral still lifes. These weren’t separate identities. The different worlds informed each other, and still do, so that a collector can put a Mapplethorpe photograph of a white lily on the office wall and there’s a considerable thrill in knowing this is a picture by the guy who photographed himself with a whip up his butt. Rodriguez is hardly in that category, but knowing that the man who photographed Rosa Parks also photographed Lucille Ball and Natalie Wood does deliver a certain frisson of its own.

As I lived with Double Vision, I found myself wondering whether there are any “great” or “iconic” pictures in the book, and ended up thinking this was probably an irrelevant question. I happened to be reading an interview with John Sypal, an American photographer based in Japan, who, among other things, runs the website tokyocamerastyle.com (there’s a book with that title, too). He says,

You know, I’ve never ONCE heard a Japanese photographer ever comment on form or structure of a single picture — instead it’s an overview of all of them at once in a set […] I’d argue that Araki and Moriyama have made plenty of truly incredible photographs that stand alone magnificently — but at the same time, the entirety of their output serves as “work” as much as single pictures do.

I think this applies to George Rodriguez, too. Photography is always a series of separate, frozen moments, but put enough of them together and they form a world and a worldview; the whole picture becomes greater than the sum of the individual frames.

And yet there’s one Rodriguez photograph I can’t get out of my head, even though it’s not especially startling or dramatic in itself. It shows Michael Jackson apparently yelling at Leif Garrett on a sports field. A caption tells us they’re at the 1977 “Rock and Rock Celebrity Classic,” but that doesn’t explain much. There’s something genuinely enigmatic about the picture. It’s impossible to tell whether Jackson’s yelling in enthusiasm or encouragement or mockery, but Garrett doesn’t seem to be taking it well. Jackson looks so confident, Garrett looks so defenseless, and they both look so youthful; Jackson would have been 19, Garrett three years his junior, but they both look younger than that. Is it over-interpreting to see that picture and think it’s a depiction of doomed youth? Well, possibly, but we know that one way or another, in very different ways, both these guys were certainly doomed. Did Rodriguez have some intuition about this when he took the picture? He surely knew how vulnerable child stars could be. In his endnote, he talks about photographic luck and the years of preparation and learning that go into becoming “lucky.” Here posterity has joined up the dots for him, and for us, and reduced the degrees of separation.

¤

LARB Contributor

Geoff Nicholson is a contributing editor to the Los Angeles Review of Books. His books include the novels Bleeding London and The Hollywood Dodo. His latest, The Miranda, is published in October.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Unknown Unknowns Come Sweeping in: On Geoff Dyer’s “The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand”

Geoff Nicholson ruminates on “The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand” by Geoff Dyer.

Riot/Rebellion: The Legacy of 1992

Steph Cha interviews Gary Phillips, Jervey Tervalon, and Nina Revoyr about the legacy of the 1992 Los Angeles “Riots.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!