Unknown Unknowns Come Sweeping in: On Geoff Dyer’s “The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand”

Geoff Nicholson ruminates on “The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand” by Geoff Dyer.

By Geoff NicholsonApril 4, 2018

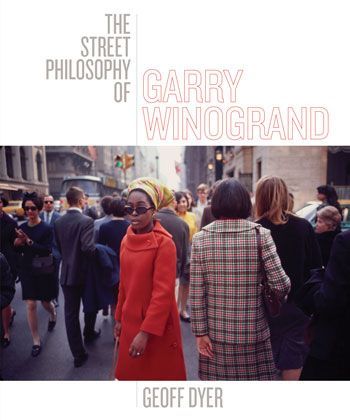

The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand by Geoff Dyer. University of Texas Press. 240 pages.

THERE ARE CERTAIN, what we might call, Rumsfeldian issues that hover around the life and work of Garry Winogrand: there are known knowns, there are known unknowns, and there are also unknown unknowns.

We know, with as much certainty as you can ever have in these matters, that Garry Winogrand (1928–1984) is one of the great American photographers, and probably the very greatest ever “street photographer,” although that’s a term that’s lost its sparkle in some quarters — and, in fact, he was just as likely to take pictures at zoos, airports, or stock shows. We also know that toward the end of his life, by almost any account, Winogrand had “lost it,” though the exact definition of that term and the deeper reasons for it in Winogrand’s case remain a subject for debate.

Within his own lifetime, Winogrand was acclaimed as a serious and important artist, with books and major exhibitions to his name, the recipient of three Guggenheim Fellowships and another from the National Endowment for the Arts. If he felt uneasy about the fame and honors that had come his way, well, so do many successful artists.

He was the son of East European immigrants, a boy from the Bronx, and many of his earliest, greatest, and certainly most recognizable photographs are the product of prowling the streets of New York, recording the people, the energy and chaos. He was always a prolific and obsessive photographer, but again, most of the best ones are.

He wasn’t only, or narrowly, a New York photographer — those fellowships funded plenty of travel — but it still seems surprising that in the early 1980s he moved to Los Angeles. He was not in the best shape, suffering from thyroid problems and hampered by a slow-to-recover broken leg. This inevitably changed his way of working. Walking the streets was not an option, so he spent a lot of time being driven around the city by his printer Tom Consilvio and others, shooting relentlessly out of the car window, sometimes apparently at random, not bothering to focus, to hold the camera steady, or even, it seems, to have a subject in mind.

Those who are sympathetic to Winogrand’s late work will say that he was deliberately testing the limits of what constitutes a photograph, consciously subverting our notions of subject matter, what is “worth” photographing and how a photograph should look. John Szarkowski, his longtime supporter, offered that view, but nevertheless wrote in the catalog of a 1988 exhibition “that he photographed whether or not he had anything to photograph, and that he photographed most when he had no subject, in the hope that the act of photographing might lead him to one.” Another charitable explanation here is that this was a response to artistic block. Winogrand knew as well as anyone that he’d lost it, and he thought the best way to get it back was to take more and more photographs until he became good again.

There are those who also say this manic activity, if that’s what it was, was caused by intimations of mortality, although that’s a harder argument to sustain. Yes, Winogrand was in less than perfect health in those L.A. days, but he didn’t appear to have any insurmountable health issues, certainly nothing life-threatening. However, on February 1, 1984, he was diagnosed with gallbladder cancer, and he died on March 19 in Tijuana, Mexico, where he’d gone in desperation, to undergo “alternative” treatment.

Now the unknown unknowns come sweeping in. When Winogrand died, he left behind approximately 2,500 rolls of film that had been exposed but not developed, about 6,500 rolls that had been developed but not printed, and about 3,000 rolls that had been developed but only printed as contact sheets — an estimated total of a third of a million “unseen” images.

These were staggering numbers even to those who were familiar with Winogrand’s working methods. He’d always appeared to be obsessive, but never this obsessive.

If he’d left no such legacy behind him, his reputation as a major artist would have been absolutely solid and assured. Although that vast undiscovered country of phantom, unrealized images doesn’t by any means destroy this reputation, it definitely changes and distorts things. Editors and curators have been agonizing about how to deal with those images ever since Winogrand died. Sometimes I think these editors and curators protest too much, but the problem of how to honor the artist’s intentions when he didn’t express any never quite goes away. However well-intentioned, all selections are provisional and contingent, they involve second-guessing, the imposition of somebody else’s tastes and preferences on Winogrand’s work.

A fair number of the “unseen” photographs, if only a small proportion of the whole, have gradually found their way into books and exhibitions, and 18 more “brand new” photographs, all of them in color, appear in The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand, by Geoff Dyer. Some of these are truly revelatory, in part because they don’t conform to the received idea of what a Winogrand photograph should look like.

Dyer has been given the freedom of the Winogrand archive at the Center for Creative Photography, in Tucson, Arizona, and the book comprises his selection of 100 full-page photographs by Winogrand, plus a dozen or so more as reference points, including a few by other photographers. Some of the Winogrand photographs are familiar, but the book is a very long way from being a greatest hits collection.

Each image is accompanied by a piece of Dyer’s writing. Most of the pieces are a few hundred words long; some are informative about Winogrand’s life and work, some locate Winogrand in various artistic traditions, including the literary (has anyone else ever looked at a Winogrand photograph and been moved to quote Gerard Manley Hopkins?), and some are oblique and surprising, yet always relevant, mini-essays inspired by a particular Winogrand image. The model is John Szarkowski’s one-volume monograph on Eugène Atget, which takes a similar form.

Dyer is a great man for the job. His writing, in this book and elsewhere, is always serious but never solemn. He’s original, eager to find unlikely connections, but you never sense that he’s trying too hard. Writing about photography is not exactly like tap dancing about architecture, but it does come with certain difficulties. There can be the tendency to state the obvious and describe the “content” of the picture, which is unnecessary, or worse, to plunge into academic art speak. Dyer does neither, although he is constantly asking, sometimes literally, “What exactly are we looking at here?” Above all, when you read his essays, you have a sense that a real human being is communicating with you. Oh, and he has a cracking sense of humor, which really helps.

I think my favorite line in the whole of Dyer’s work describes the artistic “practice” of Czech outsider photographer Miroslav Tichý. Dyer writes, in an article in the Guardian, “So, what did Tichý do, once he was kitted out with his homemade arsenal? Put as simply as possible, he spent his time perving around Kyjov, photographing women.” A truer word than “perving” was seldom written.

In a recent piece in The New York Times Magazine, Dyer described an image by Vancouver, Canada, photographer Fred Herzog, titled Man with Bandage (1968), as “a quiet belter of a photograph.” The assessment may sound offhand, but it’s also accurate, and, just as importantly, it sounds satisfyingly like the kind of thing somebody might actually say to you in conversation over a beer.

There was also his review in the London Review of Books of the catalog for the 2013 Winogrand exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art that a lot of reviewers complained was just too big. Dyer wrote,

I didn’t make it to the huge Garry Winogrand retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco but if the very large catalogue is anything to go by the show was obviously … not nearly big enough! How could it have been? Winogrand is inexhaustible.

He gets Winogrand in a way so many don’t.

¤

Geoff Dyer, of course, is an Englishman, of working-class origins, Oxbridge educated, now resident in Los Angeles. Does this give him some special insight into Winogrand? I have a memory of a passage in Dyer in which he says that as a teenager in England he didn’t feel intimidated by photography the way he did by painting or sculpture, by “real” art. I thought this must be in The Ongoing Moment (2005), but I can’t find it there; I emailed Dyer and he thought it sounded like the kind of thing he might well have written, but he couldn’t recall when or where.

I don’t want to claim too much kinship with Dyer, though we do share some biographical data — I too am an Englishman, of working-class origins, Oxbridge educated, now resident in Los Angeles — but that feeling of intimidation was true enough in my own case. Photography seemed accessible, democratic, outside the academy, and Winogrand has meant, and continues to mean, more to me than any other photographer.

His work, which initially I only saw in magazines and the occasional book, offered a vision of a world that was alien and yet, paradoxically, not completely unfamiliar. Like so many English teenagers, I knew a certain amount about the United States through its movies, its music, its art. I loved the place, or thought I did, and I was just smart enough to realize that I probably didn’t really understand it.

Winogrand’s photographs sometimes confirmed and sometimes undermined what little understanding I had. Yes, we all knew that American cars were bigger and more aggressive-looking than their English equivalents, that America looked more modern and more stylish, that there were huge skyscrapers and also wide-open spaces in America. All this was to be seen in Winogrand’s work.

But it was the people in the photographs who appeared so genuinely different. Many of them didn’t look happy, some of them looked angry, some downright crazy, but they seemed to be unhappy and crazy in interesting and dramatic ways. Even the grotesque ones still had a kind of glamour about them. Life on the American streets looked like one big freak show. There was scale, intensity, razzmatazz. It looked compelling, brash, intensely alive but not risk-free, and definitely no place for wimps. I couldn’t wait to get there.

The form of Winogrand’s photography was appropriate to the content. Things were off-kilter. Horizons and verticals were turned into diagonals, the “subject” of the photograph might be way off on the edge of the frame, might be turned into a silhouette, heads might be cut off. There was a kind of philosophical instability in the images. I loved them. I still do, and Dyer’s book has only enriched my enthusiasm.

Dyer makes life somewhat easier for himself, and that much more interesting for the reader, because he doesn’t only write about the photographs but also about the world the photographs depict, and in some cases the world they don’t.

A particularly freewheeling example (Plate 21) is inspired by a Winogrand street scene, in color, possibly of New York, though Dyer isn’t sure. The photograph is taken from inside a car and we can see the frame of the windshield and also the rearview mirror. This causes Dyer to ruminate about the special place of the “through the windscreen shot” in American photographic history. He invokes Walker Evans, Robert Frank, and Stephen Shore, and includes a direct comparison with Dennis Hopper’s famous black-and-white photograph of a Standard gas station in Los Angeles, which of course invokes Ed Ruscha, and this leads to some thoughts on East Coast versus West Coast, and on the nature of nostalgia in photography. “So which picture looks older,” Dyer asks, “the color or the black and white?” That he manages to do all this in about 300 words is all the more remarkable.

Another example: There’s a page showing a contact sheet of 54 images, from the many thousands that Winogrand took in strip clubs. Dyer writes,

Having to go to a place like this, with other men, is the opposite of bliss: it is to be in a state of despair. Your biology has programmed you to want this. But you also want love and you want your longing to be reciprocated. So to come here and see this is devastating: it is like being in hell because it is in such close proximity to heaven.

This pretty accurately sums up my own feelings about strip clubs, and probably many other men’s too, but I’m far from sure that’s how Winogrand felt.

In fact, the whole business of Winogrand and women is another confluence of knowns and unknowns. If you take pictures in the streets, then you’re inevitably going to take pictures of women, and yet there is something about his male gaze that sits uneasily in today’s culture. Winogrand thought his 1975 book Women Are Beautiful — street photographs of women, most of them apparently happy enough to be photographed — would be a surefire commercial hit, but it turned out he was wrong about that. Forty-some years down the road, there does seem to be something a bit creepy about a man wandering the streets photographing women he liked the look of, and no doubt some people detected creepiness even at the time.

Dyer is prepared to be forgiving. His selection includes the image from the cover of that book: an elegant young women standing in front of a men’s clothing store window, head thrown back, laughing uninhibitedly while holding a not-so-elegant ice cream cone. He says, “It’s hard to be censorious as Winogrand records her long hair, her sleeveless dress, her bare arms, the implied lightness of body and spirit.” Others, no doubt, would find it perfectly easy to be censorious, no less so when Dyer concludes, “It’s hard, in fact, not to fall in love,” but that goes with the territory.

Dyer’s interpretations are never exhaustive or reductive. He leaves room for your own personal version of Winogrand. There’s a photograph that Dyer describes as a man “shitting in a trash can on Hollywood Boulevard.” I’m pretty sure he means that metaphorically, but to me it looks like a down-on-his-luck guy, resting his weary bones for a moment and being justifiably pissed off when some Winogrand comes along and starts photographing him. But either way, there’s nothing to fight about here.

Dyer also wrestles with one of the most famous of the Winogrand discoveries, which was taken in Los Angeles from inside a moving car and is significantly out of focus: a Porsche heads out of the left side of the frame, a Denny’s forms a backdrop, and lying in the road is a blonde woman, face on the tarmac, knees bent, looking oddly comfortable. We can invent all kinds of narratives to explain how she got there, but we known that we’ll never know the “true” one.

Dyer, however, adds another layer of the unknown by

Inviting the possibility that Winogrand was speeding along, snapping so obsessively, mechanically … that he didn’t even see the woman who gave the shot the significance that tens of thousands of others from this phase of his life lacked.

A large part of me hopes that Winogrand didn’t see the woman, because if he did, then surely he had a duty to tell whoever was driving the car to pull over and offer assistance. If he did see the woman, took the picture, and then went on his way, well, that makes him a monster, and I don’t want my version of Winogrand to be monstrous.

Dyer’s also very good (not so surprisingly) on Winogrand’s British pictures, which have been rather pooh-poohed elsewhere. He identifies locations, observes that there’s a Man from U.N.C.L.E. ad on the side of a London bus, and spots that a black taxi cab has a license plate that begins “WUW” — “a sardonically underwhelmed attempt at wow.”

One of those British pictures (Plate 50) shows a group of people standing around outside a pub, blocking the sidewalk. Dyer writes, “If one wanted to go all Barthesian one would notice the tightness of the black guy’s trousers.” But he doesn’t want to go all Barthesian, for which we should all be very grateful. Like I said, a sense of humor really helps.

¤

LARB Contributor

Geoff Nicholson is a contributing editor to the Los Angeles Review of Books. His books include the novels Bleeding London and The Hollywood Dodo. His latest, The Miranda, is published in October.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Apertures and Aperitifs: On “The Photographer’s Cookbook”

The greatest food photography ever.

New York Trance — Geoff Dyer and the Life of the Writer

In Dyer's repetitions and leitmotifs, we get the sense of watching a mind traveling between planes of existence.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!