Moving Past Vergangenheitsbewältigung

A new novel about the project of personal and national recollection in Germany.

By Lily Hart MeyersohnFebruary 3, 2021

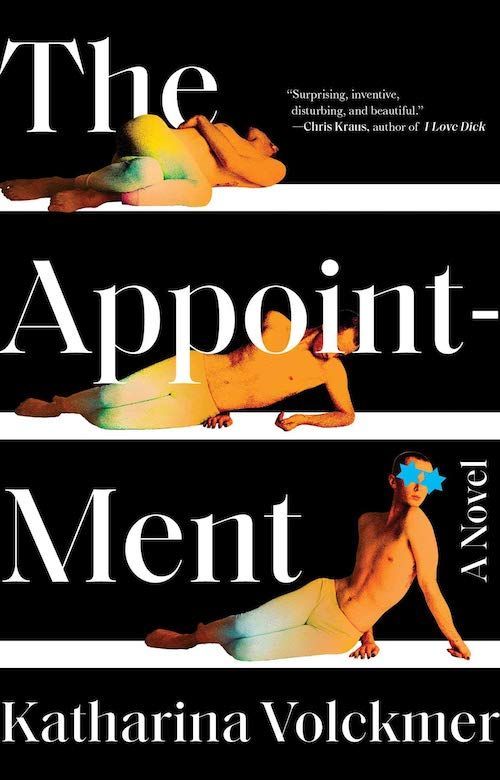

The Appointment by Katharina Volckmer. Avid Reader Press / Simon & Schuster. 144 pages.

KATHARINA VOLCKMER HAS A bone to pick with Vergangenheitsbewältigung. One of those notorious, impossibly long German words, Vergangenheitsbewältigung refers to the country’s struggle to overcome the “negatives” of its past. “I think the whole concept is wrong,” Volckmer tells me over Zoom one Friday night in November. “What do you actually mean by that? Dealing with it? Just stand there and look like you’re feeling really sorry for what happened? That’s not going to do the trick.”

Volckmer is the 33-year-old author of The Appointment. In this debut novel, which unfolds in a single encounter, a young German named Sarah visits a Jewish doctor named Seligman for a consultation. A descendant of Holocaust perpetrators, socialized as a straight, cisgender woman, Sarah is grappling with her personal histories. Bit by bit, she gives up her secrets to Dr. Seligman, asking him to help her forge a version of herself closer to the person she feels she really is.

Sarah wants what Dr. Seligman has, and what she thinks he can give her through gender-affirming surgery: a Jewish cock. She hopes that a specifically Jewish cock will not only help her feel more comfortable in her own body but also distance her from her heritage. Volckmer never lets us forget, however, that our bodies so often get in the way of this desire. “I think that our bodies know things long before our minds, Dr. Seligman,” Sarah says, her legs in stirrups. “In some cases, words can take years to follow our bodies, to say what has already been said.” For Sarah, her words are finally about to catch up to what her body has been telling her all along.

Sarah is fascinated and disgusted by the bodies of those around her and those that fill her memories, which make up much of the text. We read close descriptions of Dr. Seligman’s thinning hair; of Sarah’s belly button and hemorrhoids; of her lover K’s face transforming into a boy’s when he cries; and of her mother’s aging body as it appears in the swimming pool locker room of Sarah’s childhood. Like K, who literally becomes his child-self when accessing feelings of sadness, these images are conduits to parts of herself Sarah longs to leave behind.

Separated by paragraphs but with no chapter breaks, Sarah’s brazen voice immediately dominates the narrative. Bursts of exposition fill out her story, and ruminations, complaints, and epiphanies all get airtime. Sarah has so much to share — about sex robots, about the ending of Titanic, about German pastries, about people who think travel makes them interesting. There is nothing, so we think, that she is afraid to say. Her verbal transparency presents her as ostensibly vulnerable to the listener. But, as with so many other things, Sarah complicates this transparency. Germans don’t emerge unscathed:

People often think the German approach to nudity is very avant-garde, that it’s a sign of our liberation. […] [I]t doesn’t strike me as a symbol of freedom. […] [I]t’s a way of showing that you have nothing to hide. That your body is healthy and that you have not grown a third nipple or a lazy foot, that you have not accidentally fucked a Jew and polluted the entire race.

As a child, Sarah fell in love with opera, felt “at ease in a world of costumes and allegories.” But now she is trying to bring her full self — without costume — to bear on the mysteries of her life. Yet Sarah hides in plain sight. Casting doubt on German honesty, she casts doubt on her own. The assurance that all we must do is share and tell — that confessing is enough — does not hold up. It’s true that, with its stream-of-consciousness style, the text does initially read like a confession, or like the free association of psychoanalysis. But unlike confession or analysis, whether healing is Sarah’s primary aim is unclear. In fact, when Sarah is required by her workplace to see a talk therapist, Jason, she responds to his mindfulness slogans with deception. “All he could mumble,” she says, “was that I should never forget that I am not my thoughts.” Sarah is not asking Jason, or anyone else, to fully heal her. She is also not asking to be absolved, and by doing so, she inverts the trope of confession.

As readers, we are beholden to Sarah’s narrative, but intuitively we know that Dr. Seligman is present. He moves, touches, and responds. (“It was important,” Volckmer tells me, “that she wasn’t talking into a void.”) Dr. Seligman acts as a witness, and this witnessing implies a dynamic relationship with Sarah’s past. She is caught in a tender balancing act here, between shame for past misdeeds — those of her ancestors, which are revealed over the course of the novel — and her own potential identity as a victim of patriarchy and the gender binary.

Sarah’s personal shame reflects Germany’s national one. In her 2004 book The Cultural Politics of Emotion, feminist theorist Sara Ahmed writes that “shame as an emotion requires a witness” — such as Dr. Seligman. But Ahmed extends shame from the individual to the national level. When nations recognize their own wrongdoings — an act that often takes place through formal apology — they are able to “deal with” that past by feeling better about themselves. Germany has apologized for past atrocities, built monuments and museums, and given reparations. “But we never mourned,” Sarah declares. “We performed a new version of ourselves, hysterically nonracist in any direction and negating difference wherever possible. Suddenly there were just Germans. No Jews, no guest workers, no Others.” Sarah picks up on the sourness of that apologetic work. In her distaste for the German response, she offers a different framework for national shame, which she sees as nothing but “a facade to cover up their lack of grief.”

Sarah moves away from the sinister dangers of apology toward something more open-ended — something that does not demand feeling better. Surprisingly, that opening often occurs through humor. She mocks the Christmas market at Nuremberg as Germans’ “way of pretending […] that since medieval times […] all they ever used their ovens for was to make lebkuchen.” Volckmer plays with what she calls the “anarchic” space of dark humor, which allows the novel to evade narrow labels such as “Holocaust story” or “trans story.” Even as it shrugs off those labels, it still powerfully addresses genocide, gender identity, and transphobia.

In her 2003 book An Archive of Feelings, cultural theorist Ann Cvetkovich calls for the archiving of accounts of trauma that have been marginalized in mainstream historical studies. Feminist scholars like herself have long argued that the definition of trauma as un-representable, as in classic poststructuralist theory, does not do justice to traumas that occur through normalized structures of power. Sarah herself grapples with the trauma of loss, particularly the loss of things that she is only beginning to realize she had to lose, like the possibility of existing outside a gender binary or loving outside strict norms. This sort of trauma, Volckmer implies, is not un-representable but rather a part of life we cannot “deal with,” that should not be “dealt with.”

And so, we come again to Vergangenheitsbewältigung. “It’s a narrative they’ve become very comfortable in,” Volckmer tells me. “We’ve dealt with it, we’ve ticked this box.” But what does it mean to deal with something at all? And what can we learn from Sarah’s attempt to turn away from Vergangenheitsbewältigung toward something else?

The normative way of “dealing with” loss is to mourn: to let go. Freud distinguished mourning, where we consciously grieve a love object, from melancholia, a pathological state in which we unconsciously grieve a generalized loss we cannot identify. Volckmer’s work makes a case for melancholia. Through melancholy, we hold close to a loss and internalize it. This doesn’t suggest that all loss should be shared, however, or that we all experience it the same way. Sarah’s critique bubbles up here — about the problem with Germany’s “hysterical non-racism,” with pretending there are “no Jews, no guest workers, no Others.” A politics of melancholic grief refuses to “deal with”; it refuses forgetting or homogenizing, instead requiring an attention to deep historical through-lines — the links that run, in Volcker’s words, “from the colonies to antisemitism and anti-Blackness and xenophobia and anti-Muslim violence today. All of it.”

Ahmed argues that this specific politics of grief — one that she and other scholars identify as a queer one — allows us to internalize loss while not claiming ownership. Sarah’s retelling of her separation from her lover, K, follows a similar logic of melancholy. “I think that in a way that’s all we are: other people’s stories,” she says, in a conclusion that feels, finally, fully exposing. “I know that I am not one thing but the product of all the voices I have heard and all the colours I have seen, and that everything we do causes suffering somewhere else. […] [L]ooking back, I don’t think that K and I were ever separated along those lines.”

“I carry his grief with me,” Sarah says, “because I don’t believe that you can actually wash your hands, or your skin.” Rather, “our veins are slowly filling with each other’s stories and dirt, each other’s colours and screams.” She presents a moving but dark account of the interconnectedness of our lives and faults and the pain we create in the world. It’s by listening to K, listening and trying to understand him and his fears, that Sarah gets to a place where she can carry his grief — still his, not hers — alongside him. It’s a kind of non-possessive carrying, heeding Ahmed’s caution against the presumption of shared ownership. Sarah must hold these stories, dirt, colors, and screams, even if that only means holding the space for them. And, in doing so, she asks us to hold them alongside her.

¤

LARB Contributor

Lily Hart Meyersohn is a nonfiction writer living in Brooklyn, New York.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Germany’s New Mini-Reichs

Timothy Wright chronicles the mini-state movement in Germany.

Memory, Trauma, and the Diasporic Subject

Salah el Moncef’s vertiginous psycho-thriller, "The Offering," deals with the impossibility of a happy forgetting.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!