“Monster Portraits”: An Exploration of Identity That’s Entirely Unique

A captivating addition to the catalog of monsters in today's culture, Sofia and Del Samatar’s “Monster Portraits” strikes gold in a genre entirely its own.

By Caro MaconMay 18, 2018

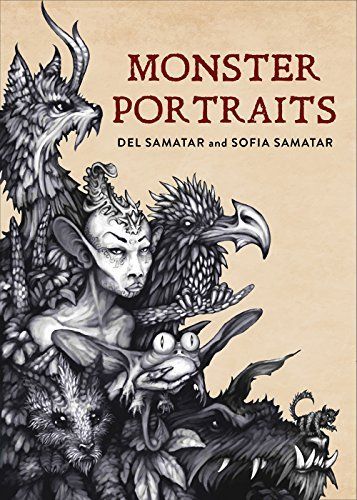

Monster Portraits by Del Samatar and Sofia Samatar. Rose Metal Press. 84 pages.

WHEN I WAS IN middle school, I took a home economics class. It was my only exposure to sewing. But rather than learning to sew something practical like a pillow or a blouse, our assignment was to sew a monster, a large, disturbing conglomeration of buttons and fabrics meant to look spooky. Mine looked like an emo teenager — hairy purple fabric hung loosely around a slab of cotton. Its bangs spiked up, revealing multiple eyes. There was nothing spooky about it. It was just silly.

Reading Sofia and Del Samatar’s Monster Portraits, I thought about my monster. “Monsters combine things that ought not to go together,” Sofia writes. “To create a monster, collect pieces of different corpses and sew them together.”

Since middle school, my understanding of monsters has evolved. What I once designed as a goofy doll, I now contemplate with admiration, complexity, and heartache. Monsters have transformed how I view feminism, from Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein to Emil Ferris’s 2017 comic, My Favorite Thing Is Monsters. The ways young people stitch together their personal identities like patchwork resonates as I move through my own life.

Monster Portraits is a striking addition to this identity quilt, a broad exploration of otherness, especially biracial otherness, and specifically the otherness of Somali Americans in the 1980s. The Samatar siblings, Sofia and Del, communicate to one another in this fantastic, hybrid autobiography of prose poetry and illustration. Sofia, author of two novels, A Stranger in Olondria and The Winged Histories, and the short story collection Tender (her story “Selkie Stories Are For Losers” was nominated for Hugo and Nubula Awards in 2014) writes the narrative. Her work draws from European, American, and Somali literary and folkloric traditions. Del, a tattoo artist, illustrates the text with elaborate, enchanting “portraits” of monsters. The result is unusual and lovely and exposes the reader to Somali-American culture through moments of vivid, phantasmic reality.

Generically, Monster Portraits does not follow a predetermined roadmap. Published by Rose Metal Press, a wonderfully monstrous press committed to hybrid-genre books, it creates its own set of rules. The book itself is for the traveler (Sofia has referred to it in interviews as “a talisman”); it is thin, the perfect size for a glove compartment, where it sits in my car for reading on the go.

The Samatar siblings set out to tell their lives through monsters “as the Egyptians told the year through the myth of Osiris.” As the Samatars casually summon this ancient African storytelling device (Sofia has a PhD in African Languages and Arabic Literature and has lived and taught in Sudan and Egypt), Sofia weaves popular culture and academic references into autobiography. The details of their journey drift in and out of various psychospaces, in which there are moments of reflection, adolescent anxiety, and self-deprecation. She jests, “[W]e were both, in our own way, failures.”

Throughout the book, Sofia examines the difficulty and ethnic ambiguity of biracial, transnational identity, and the ways such challenges open up a space for writing. “If you brave the humiliations of all the border crossings,” she writes, “where the soldiers leave you with bruises shaped like visa stamps; if you chew up the smoke of all the trains, yet leave space in your lungs for breathing; then you may come to the wedding of the Graphis.” The book portrays these visa-shaped bruises as badges of honor in a hero’s emigrant journey.

The telling of this honor shifts tonally throughout the book, alternating between the monster quest and a more quotidian narrative about the siblings and how they grew up together. These shifts in storytelling are broken up with white space that cuts in and out of sentence-long paragraphs and larger textual blocks. Generous citations at the book’s close serve as invitations for additional reading and research, like rabbit holes of thought. In this way, the book has no true end.

Sofia also displays her own research process throughout the Monster Portraits. In a section titled “The Search,” she explores Google Scholar search results for the word “monster.” Among the results she finds are “the limits of cultural hybridity” and “the monstrous hybridism of East and West.” She pairs these definitions with an illustration by Del of a cluster of animals and plants that appears to be looking far to the left, searching, as if from one hemisphere to another.

This image is an example of how the book examines the relationship between the East and West, or the long colonial history of Western cultural appropriation of the East. Sofia describes the concept of a collection, of how monsters are bodies that are owned and kept: “According to the logic of collection,” she writes, “the monster always belongs to others.” She elaborates at another point, citing a time a white person felt entitled to touch her black hair: “An elderly white woman approaches me in the park. ‘Your hair, it must be naturally curly. What’s your nationality?’ She reaches to touch my hair. I flinch. She is taken aback, hurt. The monster destroys all innocence, all fellow feeling.” This moment in the park ties Sofia’s appearance to her racial status and exemplifies the ways by which she explores her intersectionality throughout the book. She describes Somali identity in particular, “before there was language to describe us, before the ‘Other’ box on the census, before the war.” Yet before which war? The Somali Civil War, which started in the 1980s, has run the course of the Samatars’ lives thus far, and the census to which she refers is most surely American.

Monster Portraits questions why some physical traits have to be considered unusual. Sofia has cited Clarice Lispector as an influence on this book, specifically Macabéa’s famous quibble in The Hour of the Star, “[A]m I a monster or is this what it means to be a person?” Identifying with African women particularly, Sofia places herself “in the clan of Sarah Baartman,” a South African woman who was exhibited and horribly mistreated in Britain and France as the “Hottentot Venus” in the early 19th century by white supremacists who exoticized her body.

Sofia also cites Kathy Acker’s 1984 metafictional novel Blood and Guts in High School in her examination of the female body and female sexuality: “The woman who lives her life according to nonmaterialistic ideals is the wild antisocial monster; the more openly she does so, the more everyone hates her.” Fantasy doesn’t always align with the materialistic ideals of the more popular girls, underlining Acker’s point. Sofia’s biraciality may be part of the “blood and guts” in high school, susceptible to violent misunderstanding. In a confessional moment, Sofia writes, “People sometimes mistake me for a Nanny, because I’m dark and my children are blond.”

¤

Monster Portraits honors the grotesque portrayal of monsters and addresses how the grotesque is designed to elicit a response. Sometimes, it evokes revulsion or nausea, sometimes intrigue. Sofia describes how in the 1980s, “there were all those photos of starving Ethiopian children. Long fingers, heads as fragile as blown glass.” She supposes these photos were meant to produce compassion, and they did, in a spectatorial sort of way. This reaction was the true grotesque, according to Sofia: “We Are the World,” she reminisces, “What an awful song,” referring not only to the song’s pastiched vocality but also to its misdirected 1980s global-capitalist politics.

The Samatars point out the distinction between monster and monstrous, how usually the monstrous happens to the monster: “Monstrous comes upon the monster while the monster is asleep.” So rather than being the cause of fear and distress, the monster is usually the victim, and the casualty of discrimination and violence. Monstrous behavior is the result of deprivation: the monster is not someone with lack of potential, but lack of opportunity.

Like in the photographs of starving Ethiopians, monsters are exploited for the benefits of non-monsters, the tourists invading developing nations and shooting gratuitous photos of adoption centers and grocery stores. The Samatars correct this way of viewing the monster by inverting the optics. Instead, they ask the reader to wonder, “Am I the monster?”

A captivating addition to the catalog of monsters in contemporary culture, Monster Portraits strikes gold in a genre that is entirely its own. The world is familiar in the unfamiliar, like a dreamscape everyone has visited at least once.

¤

LARB Contributor

Caro Macon is a Dallas-born writer in Chicago. She is currently a Tutterow Playwriting Fellow at Chicago Dramatists.

LARB Staff Recommendations

At Play in Horror Comics

Colin Beineke reviews several new horror comics, including "The Showdown Volume 2," "H. P. Lovecraft’s The Hound and Other Stories," and "Laid Waste."

Indelible Pasts, Broken Futures

Ilana Teitelbaum on the myriad worlds and monstrous futures of Sofia Samatar's short story collection "Tender."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!