Masterful Mourning: On Dean Rader’s “Before the Borderless”

Elena Karina Byrne reviews Dean Rader’s “Before the Borderless: Dialogues with the Art of Cy Twombly.”

By Elena Karina ByrneMay 8, 2023

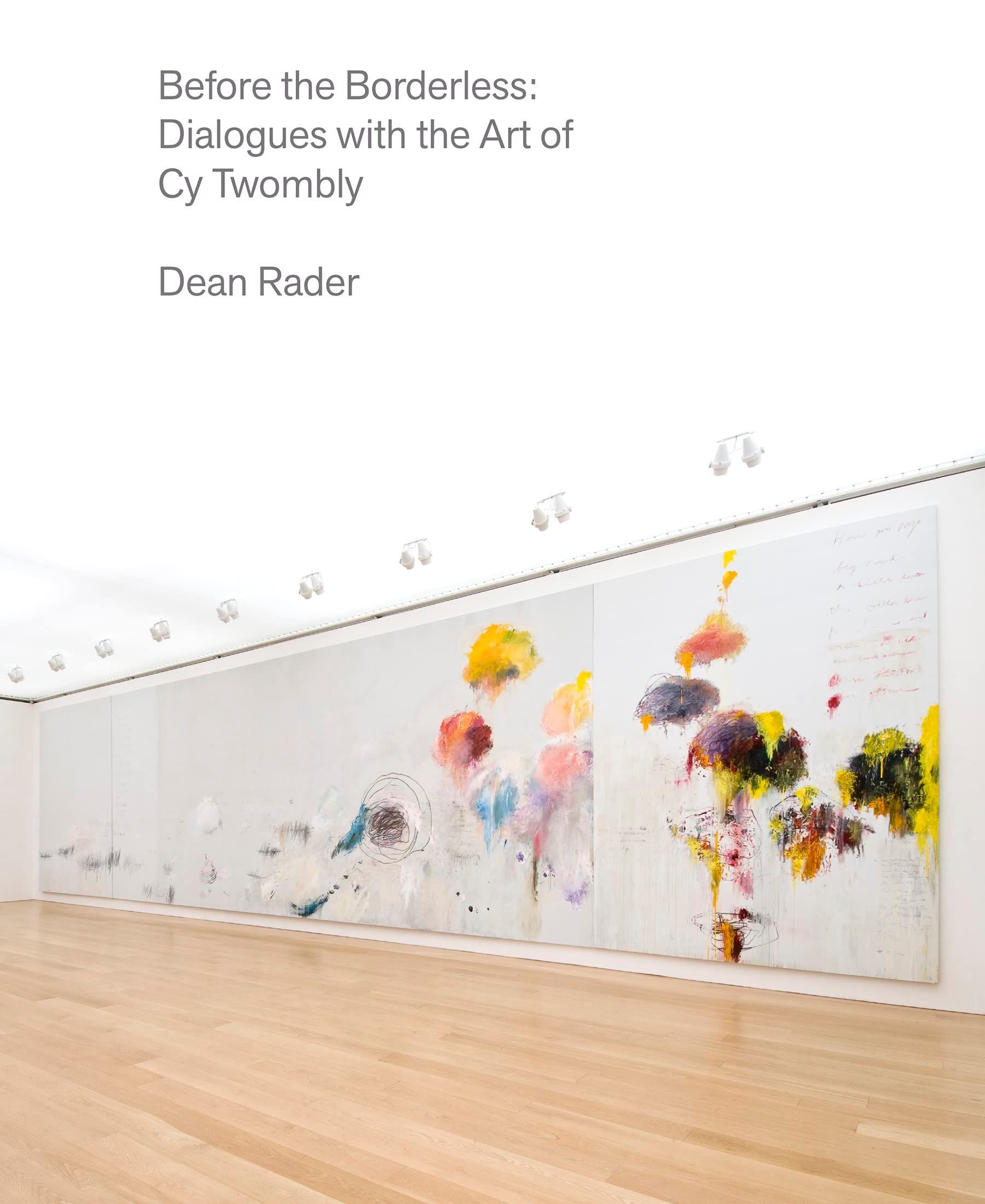

Before the Borderless: Dialogues with the Art of Cy Twombly by Dean Rader. Copper Canyon Press. 144 pages.

EXPANDING THE EKPHRASTIC tradition, Dean Rader’s stunning new poetry book, Before the Borderless: Dialogues with the Art of Cy Twombly, examines the “inscrutability of influence” between poetry and painting, and the similar relationship between loss and longing. Following his father’s passing and “the act of looking through [his] effects,” the poet travels to see abstract expressionist Cy Twombly’s retrospective, “a life’s work,” only to discover an immediate similitude of connections and parallels between the two experiences. Theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli declares that “the world seems to be less about objects than about interactive relationships” where “[t]he border is porous.” This notion that “space is not an inert box, but rather something dynamic” comes alive when you see Rader’s poems and Twombly’s works side by side.

The book’s ignited conversations (meditations, letters, sonnets, octets, studies) have everything to do with the ongoing effect palpable absence has on the author’s present-tense engagement with the world. “Out of that absence, / the questions” come, as Rader immerses himself in his grief and in Twombly’s work. Creating an empathic exchange of energy, “slowly transforming from one thing / to the next,” something new appears: an epistolary plea and a philosophical, kinesthetic investigation. This is where Rader makes himself deliberately vulnerable: “Give me sun spoor and moon melt, / give me grief’s profusion.” This “profusion” exiles the boundaries and time frames common to Western thinking. While reading Before the Borderless, we are reminded that where language “begins / duration,” art steps in to defy linear time. Rader asks, “How long does the wind spend / sharpening its knives?” Because, after all, he knows that infinity, like life and death and like emotions, cannot be measured:

Nothing on this earth is straight—

not the sky, the sea, the self, the stream—

Time is elegy, “never an arrow” that follows a straight path, and like the mourning process, “of not language but its shadow,” it suspends, surrenders, and threatens to return. Many of Rader’s titles embody these kinds of threshold actions, continuous motions, and liminal withholding, centered around terms like “circulation,” “unending,” “remembering,” “parting,” “unfinished.” Language’s lively, seductive tension always comes into play as the book balances more abstract, theoretical considerations with concrete, musical persuasions. For example, you can feel his poem “Unending Octet,” its “unraveled yarn,” its “saddle stitch, spaghetti curl, white whirl” its “ladle spill, blood roll” “[its] infinite lasso” tightening around your breath as you read it aloud. The same metaphorical vertigo can be felt when standing in front of one of Twombly’s wall-sized canvases. Since the reader cannot encounter the sheer scale of Twombly’s paintings in person, they can experience Rader’s poems as vivant referents to a fine series of accompanying reproductions of the artist’s paintings. Poem and painting become familial, coextensive, sometimes inseparable.

Rader’s intense correspondence with Twombly’s work is rich with aesthetic and personal echoes. In “Elegies (Variations),” Rader responds to Twombly’s 10 boxes that he believes were created in response to Rilke’s 10 Duino elegies—“an elegy to elegists.” Rader explains, regarding his formal response, that “each boxlike stanza is composed of four lines of four words, and each also contains a phrase from the corresponding Duino elegy: a double tribute.” The reader will celebrate how Rader’s work physically embodies Rilke’s conviction that “works of art are of an infinite solitude” and that only love can render a “fair” judgment “in understanding as in creating.” While Rader once “believed [he] could be lifted by language out of language” and Twombly’s fevered drawings and paintings look as though they transcend gravity, intimacy works as a grounding force for both poet and artist.

An implied narrative unfolds like a borderless dream, highlighting the hallucinatory impulse to juxtapose moments, place, voices, and images. Like the universe’s beautifully designed chaos, Rader’s poetry directly converses with Twombly’s work, “mending them into something akin.” In fact, the framing of these poems as “dialogues” resonates with cinematographer Walter Murch’s poetic description of the give-and-take properties of conversation in film: “Dialogue is the moon, and stars are the sound effects. […] You pay attention to the stars on nights when there is no moon.” Murch goes on to explain that the stars’ “source music can enter a scene without being perceived as a new voice.” Similarly, in Rader’s poems, vivid longing replaces loss. The gradual disappearance of one source causes us to pay more attention to another.

Acknowledging his own inspirations, Twombly said, “Art comes from art.” Just as his paintings become visibly partnered with other artists, poets, and ancient mythology, all these artifacts act like unseen partners throughout Twombly’s oeuvre. Even so, Twombly’s technical originality counterbalances these internalized influences. I sense this, too, from Rader’s tautological, unraveling lines and lexical segments:

Midhushed, cool-rooted—

these tuneless numbers of pale-mouthed prophets,

tender-eyed, aurorean …

one only adds new ink.

The human heart is a grid

in the midst of this wide quietness—

—this heart—

repository of all writing.

What is language?

Neither form nor usage—

neither urn nor autumn

The sensory-cognitive movements through the pages reinvent the poet’s voice (like artist’s brushstrokes) as they progress. Consequently, Rader’s untethered lines and repetitive, circular poem-logic mimic Twombly’s gestural, swirling drawings that float inside large open spaces on the canvas … calling to their audience:

Reader,

you and I stand once more before the borderless—

let us dissolve into it together.

Even out of context, Before the Borderless offers cryptic aphoristic declarations worth saving. Unsurprisingly, Twombly served as a cryptologist in the US army, a talent that clearly influenced his artistic style—and, therefore, Rader’s collection of poems. Rader confesses that he was not “prepared for the deep emotions his work would ignite,” and yet, just as grief is not predictable, we might assume that Twombly’s work ended up awakening or speaking to Rader’s undetermined memory of a “year of yearning and more yearning.”

Rader’s responses to Twombly’s elegiac body of work are as physical and emotionally ignited as they are intellectually apprehended. You’ll find a beautiful example in the poem “Meditation on Instruction,” which begins with a direct description of Twombly’s Untitled (1970) before turning toward the implied “glume and awn” often found in memory’s cinematic landscape:

When I was a boy, my grandfather walked me around the rim of our family farm. Wheat and more wheat. Nothing but wheat. Barely soil, barely a hill. It was Sunday. He was still wearing a tie. His shirt was the color of the wheat: his tie brown as the dirt the wheat bequeathed. If you stand here long enough, he said, you will learn everything you need to know.

Rader captures the poignancy of this childhood moment with his grandfather through a visual accumulation of landmarks of the ordinary, even a “tie brown as the dirt the wheat bequeathed,” because by remaining in the presence of another’s life, paying attention, one can learn everything about the making of that life, and about relationships. Just as Rader stands in this memory of his grandfather, his poems glitter and bestow knowledge derived from the surrounding art of Twombly. In turn, Twombly’s images invite us to appreciate the visual movement of Rader’s poems. Just as Rader’s elegiac unknown waves “its wand, / and a beam of light disappears into the sky’s black hat,” the living conversation of poems and paintings in Before the Borderless puts the reader in touch with the “everything [they] need to know.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Former regional director of the Poetry Society of America, Elena Karina Byrne is a freelance editor, lecturer, author, programming consultant and poetry stage manager for the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, and literary programs director for the historic Ruskin Art Club. A Pushcart Prize and Best American Poetry recipient, Elena served as a final judge for PEN’s “Best of the West” award and for the 2016–18 Kate and Kingsley Tufts Poetry Awards, as a 2018–19 Georgia Circuit visiting poet, and as last year’s co-judge for the international Laurel Prize, an annual award for the best collection of nature or environmental poetry. Her books include If This Makes You Nervous (Omnidawn, 2021), No Don’t (What Books Press, 2020), Squander (Omnidawn), MASQUE (Tupelo Press, 2008), and The Flammable Bird (Zoo Press/ Tupelo Press, 2002).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Two Roads: A Review-in-Dialogue of Jenny Xie’s “The Rupture Tense” and Monica Youn’s “From From”

Victoria Chang and Dean Rader review Jenny Xie’s “The Rupture Tense” and Monica Youn’s “From From.”

Two Roads: A Review-in-Dialogue of Roger Reeves’s “Best Barbarian”

Victoria Chang and Dean Rader consider “Best Barbarian,” a collection of poems by Roger Reeves.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!