Lying, Archiving, Surviving: On Fernanda Melchor’s “This Is Not Miami”

Philip Luke Johnson reviews Fernanda Melchor’s “This Is Not Miami.”

By Philip Luke JohnsonAugust 11, 2023

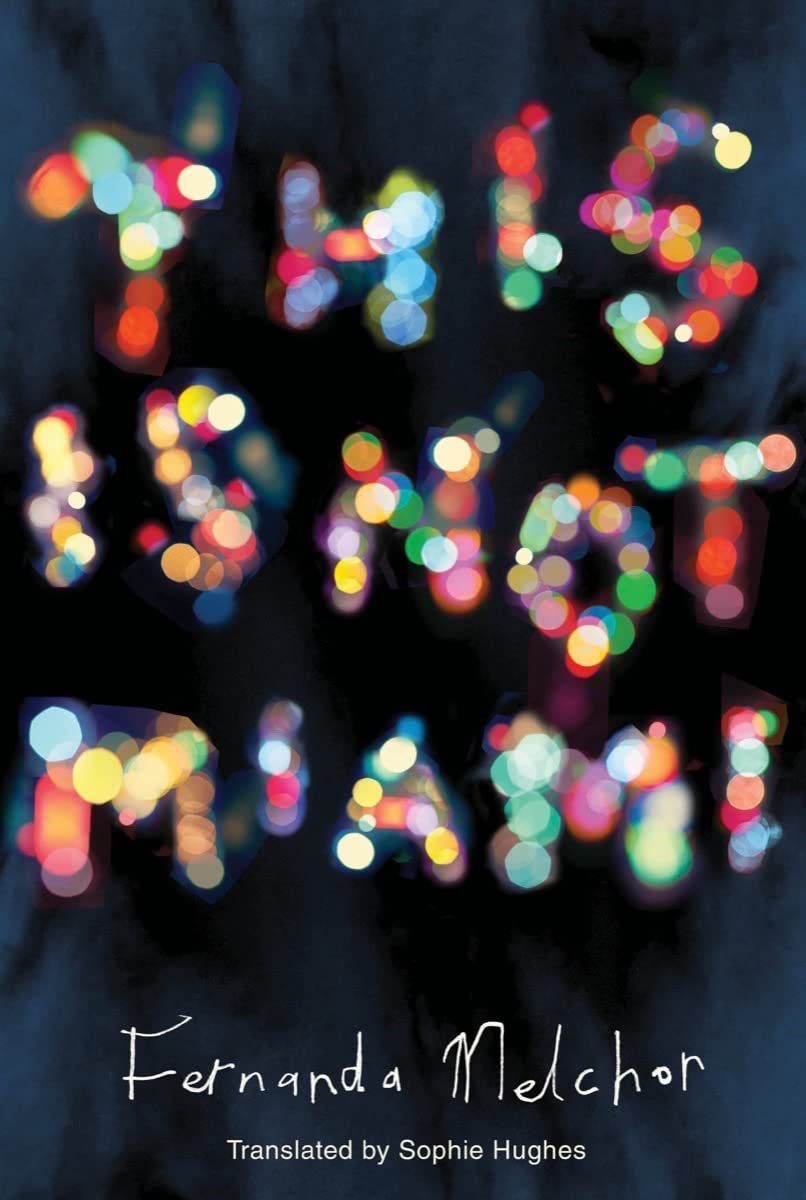

This Is Not Miami by Fernanda Melchor. 160 pages.

WALKING BY HER old elementary school, an unnamed narrator notices the broken pieces of a memorial to a woman found murdered at the site. Fascinated by the case, the narrator unearths newspaper reports claiming that the woman was a government employee who had been kidnapped, but the name on the memorial doesn’t match the name in the reports. Two women dead or disappeared, but only this single, forlorn memorial to two lives otherwise erased from the city.

This vignette, from Fernanda Melchor’s newly translated collection of stories This Is Not Miami, will seem familiar to readers of the author’s novels. Casual brutality, disregard for the dead, and violent contempt for women feature prominently across her work. But this vignette is different. For one, there is no ambiguity around who is responsible for the violence. For another, the woman who finds the memorial in this story could be Melchor herself.

This Is Not Miami is a collection of vignettes from Melchor’s early years as a writer in Veracruz, a port city on Mexico’s gulf coast. The book is made up of 12 “relatos”—tales or accounts loosely based on true stories—but some of these contain multiple vignettes threaded together by a common theme. Many of the vignettes were related to her by Veracruz locals and then retold by Melchor, while others are her own tales.

Melchor offers her own take on the relato genre in an author’s note, and with it a glimpse of her method as a writer. She describes her intention to “tell a story with the maximum amount of detail and the minimum amount of noise.” But she is particular about what counts as detail and what is noise. Her relatos are not forensically detailed reports like in the crime pages or the nota roja tabloids of Mexico. Those are noise. Instead, Melchor aims for honesty in a subjective impression of events. The events are true but always experienced from a close proximity full of disorienting details.

This Is Not Miami was Melchor’s first book, published in 2013 (and again in 2018) as Aquí no es Miami, but it is her third work translated into English. In the decade between the Spanish and English publications, Melchor has soared to national and international acclaim; her novel Hurricane Season was published in English in 2020 and short-listed for the International Booker Prize, while Paradais was published in English in 2022 and long-listed for the International Booker.

Sophie Hughes translated each of these texts into English, and again in This Is Not Miami, she captures the swaggering vernacular of Melchor’s Veracruz. Only one of the relatos, previously unpublished, uses the lengthy, polyvocal paragraphs of Melchor’s later work. The others showcase Melchor writing, and Hughes translating, in a lighter and more conversational style.

The collection of relatos can certainly be read as a precursor to the novels. Familiar tropes from the novels appear in some form across the relatos: tales of vindictive spirits, youth flirting with catastrophe, violent killers who must not be named. This is the same Veracruz we encounter in Hurricane Season and Paradais, but we see it from a different perspective.

Melchor is very much a character within this account of Veracruz. In some cases, speakers address her by name, while in others, the narrator matches Melchor’s profile: a bookish kid growing up in the 1980s and ’90s before starting a career in journalism. The Melchor that emerges across these relatos is a skeptic and archivist, and this places her in an outsider position. In the longest relato, “The House on El Estero,” she describes Veracruz—or the segment with which she is so fascinated—as “a culture that mocks the written word and dismisses the archive, preferring testimony, oral and dramatic accounts—the joyful act of conversing.” Melchor’s relatos are presented as dramatic conversations, a speaker holding forth and captivating a barroom audience. But while Veracruz mocks the archive, Melchor takes it upon herself to compile a vernacular archive of her city.

She also tries to understand what is behind these tales. She reads up on demonology to make sense of an exorcism in “The House on El Estero.” In “Don’t Mess with My Boys,” which narrates the arrival of crack cocaine in Veracruz, she notes that the drug’s addictiveness is not fully explained by science. In “Queen, Slave, Woman,” she cites Michel Foucault’s 1973 book I, Pierre Rivière, Having Slaughtered My Mother, My Sister, and My Brother: A Case of Parricide in the 19th Century and his idea that “every crime must serve some purpose to society.”

This focus gives a characteristic form to many of the relatos. They begin deep within—up close against—a speaker and their impressions of the city. Locked into the speaker’s perspective, we learn of something mysterious or macabre. Desperate stowaways on a cargo ship coming ashore and mistaking Veracruz for Miami. A prison emptied out with little forewarning.

Having set up the mystery, the perspective of the relato shifts. This comes with Melchor’s investigation, her attempt to find the broader context, the rational explanation. With the shift comes a glimpse of the bigger picture of Veracruz. This is never a complete picture, but it is often enough to catch something of the machinations of the city’s elite, its politicians, its narcos. Where Melchor is able to get to the bottom of the story, she reveals the schemes and caprices of these people in high places. Power is so stratified that ordinary people experience the results of these schemes as incomprehensible, arbitrary mysteries: ghosts and impossibilities and sudden bursts of violence.

“Lights in the Sky,” the first relato in the volume, encapsulates this narrative approach. On a trip to Dead Man’s Beach in Veracruz, the nine-year-old Melchor sees strange lights moving fast across the night sky. She interprets these as UFOs, getting caught up in a burst of public fascination with extraterrestrials. The mystery is casually punctured when a family friend observes that the lights are from narco planes. These clandestine flights traffic cocaine into Veracruz, seemingly under the supervision of the Federal Judicial Police.

The penny fully drops for Melchor years later when she reads an old newspaper story about the landing strip used by many of these flights, and on which soldiers ambushed the federal police escort (it is unclear whether the police were chaperoning or apprehending the cocaine), killing seven officers. An enigma gives way to corrupt policing, strife among government factions, and brutal violence. This is the pattern of Melchor’s relatos. Compared to the witnesses of some of the other enigmas, young Melchor emerges relatively unscathed from this revelation.

“Lights in the Sky” frames This Is Not Miami in another way. It acts as an origin story for Melchor the writer, the investigator of macabre Veracruz. Reflecting on the revelation, she writes, “I don’t think I’ve ever believed in anything the way I believed in extraterrestrial beings.” Throughout the rest of the relatos, Melchor collects similarly mysterious stories, but she also tries to see through them to what’s really happening in Veracruz.

After learning the truth behind her belief in extraterrestrials, Melchor says of that belief and those stories: “They were just lies, the inventions of grown-ups.” It is a classic coming-of-age, loss-of-innocence line. But in This Is Not Miami, the lies take a specific form. No particular grown-ups have deceived her—her father found the fascination with UFOs ridiculous—but the world appears as one big lie or cover-up. The incident involving the ambush of federal police was a rare case of the truth evading government censors.

The deceptions of ordinary people in This Is Not Miami are not these major conspiracies or elite schemes. Rather, they are the silences, the rumors, and the superstitions that conjure a world of ghosts to explain extraordinary events. The lies are the decision not to ask questions or investigate.

In one relato, sinister guys at a club—whom everyone understands to be narcos—drag a person outside and beat him. One of the guys addresses the room: “Nothing to see here. Or did one of you see something?” Everyone saw everything, but this is the lie, the code of silence to live by in Veracruz. Better not to see the soldiers, the narcos; better not to talk to the media.

¤

Melchor does not get to the bottom of every mystery; her skepticism cannot debunk every tale. “The House on El Estero” is a horror story about an inexplicable exorcism. It is framed by Melchor’s partner—her future partner at the time of telling, her ex at the time of writing—relating the story and Melchor interjecting with questions and doubts.

The revelation in this relato is not about Veracruz but about Melchor. She is fascinated by the story and captivated by the storyteller. But they “lived in different worlds”—she the investigator and archivist, and he a member of the culture that dismisses the archive. She hints at a difficult incompatibility, between herself the outsider and the people and world that fascinate her.

Melchor’s fiction has no such outsider figure, able to question and sometimes glimpse the bigger picture or the behind-the-scenes machinations. The fictional characters are completely submerged within the maelstrom of Hurricane Season or the stasis of Paradais. They experience mystery and catastrophe but cannot or will not investigate further. They live within the deceptions.

But with Melchor as a character, exploring and archiving Veracruz, we do get a clearer picture. While this Veracruz is similarly bleak to the one we see in her other works, it is also Veracruz positioned within a specific context. We follow along as Melchor traces changes during a grim period for the city and state: the governorship of Fidel Herrera Beltrán and the takeover of the state by Los Zetas.

Recruited from elite military units by the Gulf Cartel in the early 2000s, the Zetas brought the terror of US-backed counterinsurgency—forced disappearance, torture, mass execution—to the cartel’s east coast domains. They dressed in ski masks, traveled in armored convoys, and deployed sophisticated weaponry and tactics to conquer and control turf.

The Zetas also maintained control of Veracruz through high-level corruption. Herrera, the state governor from 2004 to 2010, worked with the criminal organization, enriching himself and putting local police forces at the disposal of the Zetas. His successor, Javier Duarte de Ochoa, embezzled funds on a truly massive scale. These governors made Veracruz the most dangerous state in the country for journalists. In 2016, the year that Duarte left office, the largest mass grave in Mexico was discovered in Veracruz. It contained over 300 skulls.

Melchor’s Paradais features a criminal group based on the Zetas, but the group is referred to simply as them. No one dares speak their name; everyone knows what that hushed term refers to. Here again are the lies and evasions of grown-ups, but in the novel, there is no Melchor figure to investigate and make sense of the dark shadow cast by them.

The entire final section of This Is Not Miami, by contrast, is an exploration of the Zetas’ reign of terror. A decent guy who can’t catch a break gets recruited by the Zetas. Families are awakened by gun battles in the street. It is not clear whether cartel gunmen or soldiers are behind the violence, but the larger explanation is clear: this is Veracruz under the Zetas.

For a few years, the impact of the Zetas on Veracruz, and on Mexico itself, was so profound that they changed the vernacular, the way people spoke. A culture of joyful conversing and barroom braggadocio learned silence and circumspection.

These learned ways of speaking pervade This Is Not Miami. The final relato is entitled “Veracruz with a Zee for Zeta,” a variant on a familiar formulation for talking about areas under the dominion of the Zetas (zeta is the Spanish word for the letter z). Óscar Martínez’s 2016 book A History of Violence: Living and Dying in Central America, for example, contains a chapter called “Guatemala Is Spelled with a Z.”

¤

Over the course of This Is Not Miami, a picture emerges of the Zetas’ takeover of Veracruz. Petty crime is consolidated into one vast racket; people get killed or disappear, but no one dares voice the names of the perpetrators; the police and military respond violently, but it is often unclear whether they are operating with or against the Zetas. Ordinary people hunker down, learn not to see or say anything, and survive as best they can.

Melchor moves through this world, compelled by macabre and mysterious stories, while always standing a little outside of them. Because of her skepticism, because she investigates, we can glimpse what is behind all this violence—the schemes of the governor, the work of well-connected narcos. This wider perspective also implies that the current violence, the shadowy machinations in high places, will pass or change. By naming actors calling the shots in Veracruz, Melchor also allows us to trace their paths beyond the end of the book. The Zetas have splintered into warring factions, still wildly violent but not the power they once were. The political party of Herrera and Duarte has finally been ousted.

Hurricane Season ends with the idea that the grave is the only way out of the dark times in Veracruz. This Is Not Miami also ends on a note of despair, but for a particularly bad time in Veracruz that could one day pass. And it might actually be possible to see out and survive the horror, to find its limits and look beyond them.

¤

LARB Contributor

Philip Luke Johnson is a lecturer in writing at Princeton University. He holds a doctorate in political science from the City University of New York, and researches crime and violence in the Americas.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Beautiful and Terrible Paradise: On Fernanda Melchor’s “Paradais”

Marcus McGee contextualizes Fernanda Melchor’s “Paradais,” translated by Sophie Hughes.

Mutations of Warped Manliness: Selva Almada’s “Brickmakers”

A brilliant, nuanced novel about the links between masculinity and violence in Argentina.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!