A Light on Vivian Maier

Emilie Bickerton reviews Pamela Bannos's "Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife."

By Emilie BickertonNovember 23, 2017

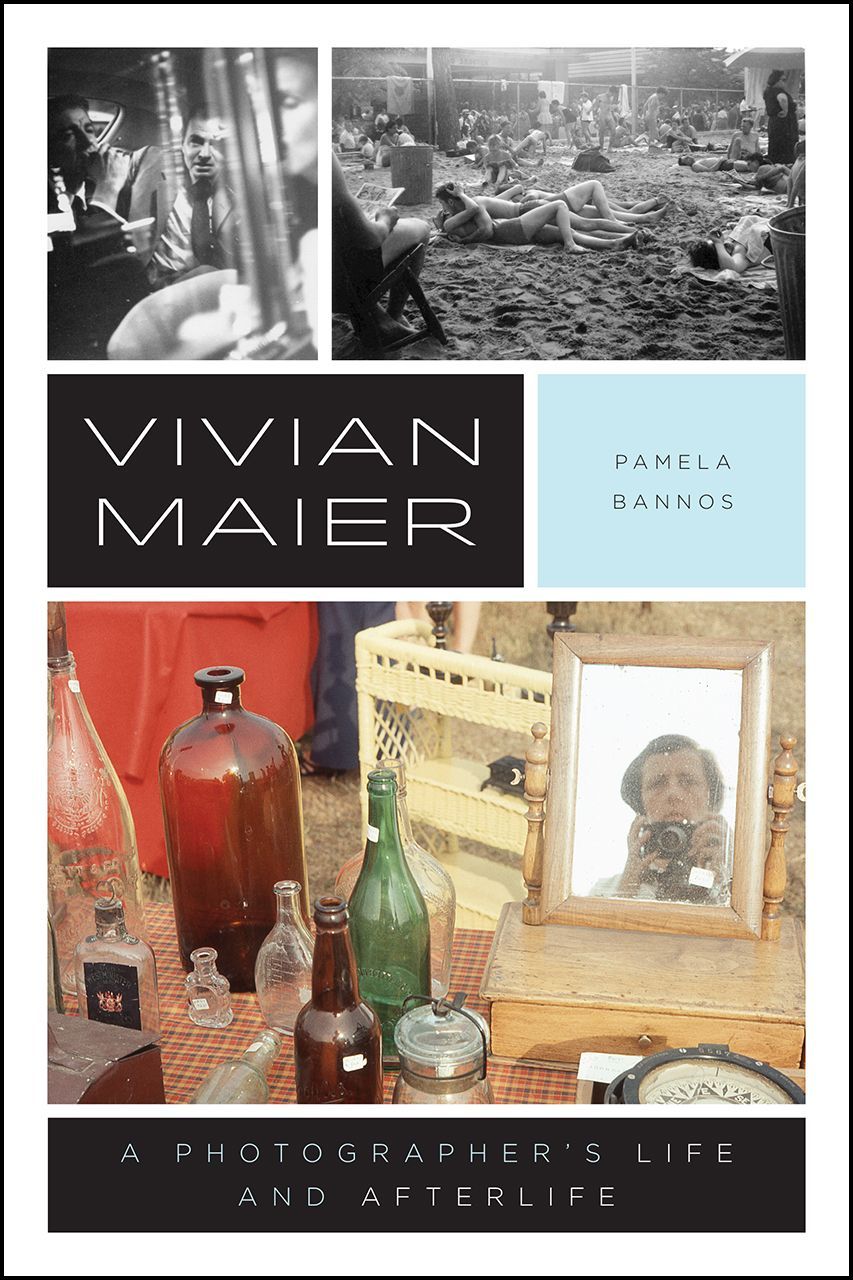

Vivian Maier by Pamela Bannos. 352 pages.

TO MANY, Vivian Maier is known as the mysterious Chicago nanny who took photographs secretly — thousands and thousands of photographs, often left as undeveloped rolls of negatives, which she then boxed up and stored in lockers. She was perceived by the locals in her Rogers Park neighborhood as a cantankerous old bag lady who ate food out of cans. Nobody knew about her art. But in the months before she died on April 21, 2009, aged 83, her storage lockers went into arrears. The padlocks came off, and all her photos and old cameras, her stacks of newspapers, magazines, and other items, went up for blind auction. One buyer bought the whole lot, and put it up for sale again in four or five subsequent auctions, thus setting in motion the scattering of Maier’s work. Some buyers, curious about the photos they found, began posting them on the internet.

The discovery of Vivian Maier caused a sensation in the art world, and her story has captivated many. It is, after all, a tale of mystery and intrigue: a woman who works as a nanny, never marries, says almost nothing about her life and childhood, dies in obscurity, dwarfed by the belongings she hoarded, only to be unveiled as one of the boldest and most poetic street photographers of the 20th century. It is difficult not to be fascinated by the woman, who can be glimpsed in the various self-portraits she took throughout her life, casting her distinctive shadow on a pavement or a wall — the tall, austere figure with an angular face and a beguiling stare, always smartly dressed in 1950s-style skirt suits or overcoats regardless of what decade it actually was.

This is exactly the story Pamela Bannos, in the first full biography of Maier, sets out to discredit. Vivian Maier: A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife is intended as “a counterpoint, a counternarrative, and a corrective” to the narrative spun primarily by the buyers of Maier’s boxes at the auctions of August 2007, and in particular, former real estate agent John Maloof, who has done more than anyone else to make Maier visible. As one blogger put it in 2014, Maloof could be described as a man who “just found an old photo in storage, attached [his] name to it, claimed all rights and sold limited editions of that photo for thousands of dollars.” It is difficult to avoid Maloof when seeking out Maier’s photography. He has published three books of her photos and made a documentary, Finding Vivian Maier, released in 2014. When the productions are not in his name he has shown less enthusiasm however: he refused to collaborate when the BBC arrived in Chicago to make their own documentary on Maier for Alan Yentob’s Imagine series; when Bannos began working on this biography, Maloof set such high demands she found it impossible to work with him, thus denying her access to his collection.

Maloof is, undoubtedly, the archvillain in A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife, cultivating the image of the “mystery nanny photographer” and even admitting this was what kept him going. “If I knew all about her, I don’t think I'd be as interested,” he says. But he is also the figurehead of a deeper problem dogging all Maier scholarship: given that she was so secretive, and that her oeuvre has subsequently been so dispersed, can we ever build a true picture of the artist? To this, Bannos simply follows the photographs, tracing where Maier went and looking at what subjects drew her eye. Her approach is refreshing — a clear-eyed, empirical account that counters the willfully obscure, ego-driven yarns spun by the buyers. In this light, A Photographer’s Life and Afterlife is a work of real integrity in a field lacking such a genuine spirit of inquiry.

The biography proceeds by dual narratives, shifting between recounting and retracing Maier’s life, and the story of how her oeuvre was subsequently “discovered” following the auctions — Maier’s life, in other words, and the afterlife of her work, told in parallel. This jumping across time has its drawbacks for the flow of the biography. With the constant shifting from one epoch to another, we become less immersed in Maier’s life, and, perhaps as a by-product of this, Maier’s childhood in New York and France, her work as a nanny, the heyday of her photography in New York and Chicago throughout the ’50s and ’60s, and then her slow decline from the ’70s onward lack intensity. It is clear the nature of Maier’s photography evolved as the world around her changed, just as the cultural, social, and political atmosphere in the previous decades infused her work and likely influenced her behavior. But when Bannos describes this context, and offers some color and detail on the developments in art and photography, the shifts and controversies in society and politics, the prose can be clunky and dutiful — paragraphs are often tacked onto sections, as though to do the job of contextualization in a few lines, but evoked without much passion. A deftness of touch in knitting together biographical material with the historical situation is lacking.

One forgives Bannos, however, because she directs her energies on getting the counternarrative right, and this she manages admirably.

Maier’s choices to not share her history or her photography also seem vital to seeing her as a woman who did her best to control the way she was seen, as well as how she viewed and recorded her surroundings. Maier found men to be “uncouth” yet her legacy has been almost entirely in the hands of men — something we cannot ignore when considering how her life and work have been depicted.

The facts about Maier’s life unearthed by Bannos take us to New York first, where Maier was born, on February 1, 1926. Her mother, a Frenchwoman named Marie Jaussaud, had left the Champsaur Valley in the Alps in 1914, following in the footsteps of her own mother Eugénie, who had sailed to New York in 1901. Both worked as domestic servants. In New York, Marie met Charles Maier and had two children with him, Karl and Vivian. Their union was brief. In 1932, as the Depression hit its lowest point in the United States and work was scarce, Marie took her daughter back to France, where they stayed six years before returning to New York. There, Maier would begin to work as a nanny, earning enough to travel — first to her family’s home in France in 1950 and 1951, where her first known photographs were taken, and then in 1959, for a trip around the world, alone. Maier’s last employment was in 1996 in Chicago. Thirteen years later she died, in a city hospital. One of the children she had looked after as a nanny identified her body and organized her funeral. Maier herself never married, never had children, and was not known to have had any romantic relationships.

We cannot know for sure what influence Maier’s upbringing had on her photography, and Bannos resists speculating. It seems Maier both followed the path open to her, working as she did as a nanny, and at the same time made a conscious effort to break with her family and origins. She never spoke about her private life and she changed details on her birth certificate and other identification papers, suggesting she was doing her best to live a free life, as much as this was possible to her. “Her separation from her own family,” Bannos writes, “as she assumed an outsider’s role [as a nanny] among others stands out as a poignant reminder of her independence and self-determination.” None of this indicates a pathway to photography however, making her decision to devote her life and most of her money to the pursuit remarkable.

Maier’s oeuvre is thrilling to explore, but it remains disturbing to think how her privacy in life has been so compromised after her death. This also raises broader questions about orphaned art works and what drives artists to create in the first place. Asked by one acquaintance who glimpsed a few of her photos why she would not show her work to anyone, Maier apparently replied that if she had not kept her images secret, people would have stolen or misused them. Given the exposure of her work today, its proliferation online, in books, and in galleries, one wonders whether she would have been horrified by all the attention. She chose to remain unknown. We cannot even say if she self-identified as a photographer. Every house she lived in as a nanny she asked for a padlock on her bedroom door; whenever she went out alone to take her photographs she refused to say where she was going and got angry if asked; in her bookcases, she turned the spines of her books against the wall so the titles remained hidden. All these details suggest Maier wanted her anonymity to remain intact, and perhaps she never imagined she had anything other people might care to see.

But she is dead, she left no will and made no apparent attempt to determine the fate of her photographs. Should we honor what we think the artist might have wanted? Maier’s oeuvre joins the other art collections, discovered by strangers, in an age of freewheeling circulation of images on the internet. In many ways, Maier and the various ways she has been understood, from the “mystery nanny” to the “street photographer,” is a construction and reflection of our time and much less of her own. This is what makes Bannos’s biography so welcome. For the most part she lets Maier emerge simply from what she did — her travels, her photos, her actions. Only in her closing remarks does Bannos give us the swiftest brush strokes of a portrait, which is worth remembering for it is one of the most lucid and accurate summations of Maier’s work to date.

Vivian Maier was a fiercely independent woman who lived the life of a photographer while also working as a nanny. She had a difficult personality, she was a hoarder, and she sought anonymity. These qualities may ultimately have little to do with her photography, but together they form a picture of a woman who chose to remain unknown.

There are two mysteries around Maier that are neither disrespectful nor irrelevant to pursue. The first is practical. Why did Maier stop taking photographs so abruptly in the ’80s? She would live another three decades. Did she stop? We cannot be sure. All we know is that almost all her known prints were packed up by the end of the ’60s, also around the time she stopped developing her black-and-white film — “a choice that today contributes to multiple readings of her intentions,” Bannos writes. For the next 40 years, Maier carried all her material with her in boxes, alarming new employers, some of whom would give over their garages and attics to store her belongings. Maier’s downward spiral began in the mid-’70s, by which point the subjects of her photographs had changed — the vivid, moving portraits of people started to disappear and were replaced by trash on the street, countless newspapers, fresh piles off the press or single copies torn and discarded. This was an evolution, but was it announcing an imminent end? Or have we simply not discovered all the work from later decades?

The second mystery is more essential, and unknowable. Why did Maier take photos and live the life of a photographer if she did not want to show her work or ever have it seen? It is moving to imagine her working so privately, without any apparent desire for recognition or visibility. What drives an artist to create, detached from any thought about reception or market, or apparently any desire to communicate through the art? If Maier was not interested in any of this, it is admirable — and also odd. The attempt to communicate an idea, an experience, or an emotion drives much artistic creativity, even if that artist has little interest in her potential audience. With Maier however, we must consider the possibility that she was not interested in communicating anything to anyone.

Another possibility is Maier feared the reception she would get because of the nature of her photographic process, which often involved prowling and stalking strangers. But if she simply lacked faith in the interests and motivations of others, should they get their hands on her photographs, this leaves us to wonder: If Maier had such little faith in other people, and no intent to have her work seen, why did she not do more to safeguard her oeuvre? By boxing it up in storage lockers, and then not paying the rent, she was leaving it to the wolves. She could have avoided all this by destroying it, and ensured absolute privacy and obscurity to the end. Given what we now know about Maier, this final abandon she showed with her oeuvre is baffling. Perhaps the idea of destroying it was, understandably, unbearable, or perhaps some part of her did want the world to see it eventually. And perhaps, ultimately, she was just too tired, in the end, to deal with all that.

¤

LARB Contributor

Emilie Bickerton is the author of A Short History of Cahiers du Cinema (Verso) and the screenwriter of the film Amnesia, which was released in 2015.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Magnetic and Complicated Personality

A review of Harvey Sachs’s new biography of Arturo Toscanini.

On Anna Maria Maiolino’s “Entrevidas” (Saturday, September 16, 2017)

Martin Harries on a recent performance of Anna Maria Maiolino's "Entrevidas," which will be performed again on November 5.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!