Life, Disturbed: On Nicole Flattery’s “Nothing Special”

Grace Linden reviews Nicole Flattery’s “Nothing Special.”

By Grace LindenJuly 16, 2023

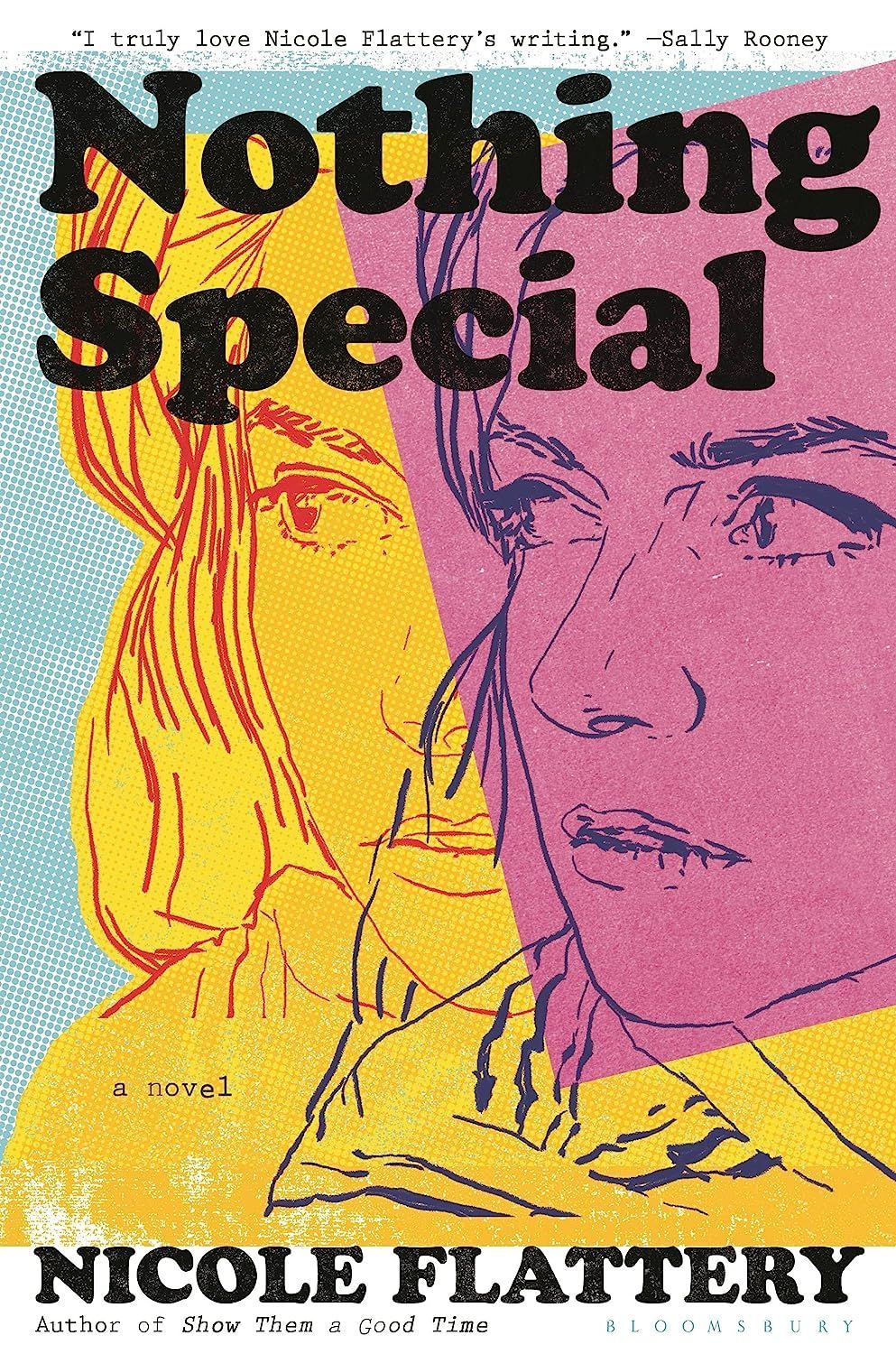

Nothing Special by Nicole Flattery. Bloomsbury. 240 pages.

IN 1965, Andy Warhol began recording his conversations with Robert Olivo, better known as the actor Ondine, as well as Lou Reed, Edie Sedgwick, and a whole roster of other regulars at the Factory, the studio Warhol kept in New York City. The artist had decided to write a novel, a contemporary riposte to James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), and planned to make the recordings his text. Over a few different sittings, roughly 24 hours of material was gathered, and in the fall of 1968, two high schoolers were hired to transcribe the material. Though their names were excluded from the cover and copyright page, Warhol did mention “two little high school girls” who worked at the Factory, “transcribing down to the last stutter” in Popism: The Warhol Sixties, his 1980 memoir. In 1968, a: A Novel was published with all the spelling errors and mistakes that they had made.

This is the setting for Nicole Flattery’s debut novel Nothing Special (2023), the title of which is also Warholian, the proposed name of a proto-reality, hidden-camera television show that the artist dreamed up but never made. Flattery’s Nothing Special opens, however, much, much later—in 2010, when Warhol has been dead for more than two decades and Mae, now a former New Yorker living in an unnamed town, is visiting her dying mother in the nursing home where she lives.

Then the timeline switches, and it is 40 years in the past. Mae is a 17-year-old, with an alcoholic mom and no father, who mostly has been muddling her way through life. In the way that only makes sense to a high schooler, she suddenly finds herself ostracized by her peers, a demotion that she accepts in stride. “I wanted to have a very profound experience,” she says, a very teenage thought. She begins to spend afternoons riding department store escalators, enjoying the serenity of the shops, the “comfortable” women, the performance of being seen. “Every day that week, I smoothed down my t-shirt and brushed my hair in the bathroom before I stepped on the escalators,” she recounts. “I felt, as I moved, that I was more available for public consumption than I was at school. The adult atmosphere suited me.”

Warhol may be mostly famous for his silkscreened soup cans and portraits of Marilyn Monroe, but in some ways, his entire life was a work of art, espousing downtown cool and cultivated mystique. That was perhaps his most radical choice; what made Warhol such a visionary was his complete insistence on the idea of lifestyle as aesthetic experiment. Public performance today would be nothing without him—though his maxim about everyone in the future receiving their 15 minutes of fame fails to imagine the constancy of that performance turned surveillance turned performance again.

As Mae continues to explore her own version of public performance through her visits to the mall, weeks go by. She meets a man while riding the escalators at Macy’s on Herald Square. They sleep together, and only then does Mae feel herself begin to slip away. She gets lost at school and loses the threads of conversations; she envisions destroying her friend Maud. In hopes of gaining a diagnosis, she pays a visit to a doctor who doles out pills and prescriptions to New York’s society women. Flattery took the doctor from Popism, where he plays a bit part; in Nothing Special, he has been elevated to a recurring character. This doctor says Mae needs an occupation and tells her to go ask for a job at a studio on East 72nd Street. Eager for her “whole life to be disturbed,” Mae rings the proverbial bell at the Factory.

And so, Mae begins her quasi-receptionist job, typing endless pages with a dedication and commitment reminiscent of eager but unpaid interns. Remuneration is never discussed. She works alongside Anita, Dolores, and her soon-to-be best friend, Shelley. After proving herself relatively capable, Mae is given a new assignment: working with Shelley to transcribe Ondine’s recordings verbatim. She quickly loses herself in the taped voices—their screeds, non sequiturs, and amphetamine-fueled musings. “Behind us life was technically happening, but we had no part in it,” she thinks. “We were trapped in their world from two years ago.” Time’s movement and malleability are central to Nothing Special: Flattery shifts between days and decades, revealing how quickly everything goes even as time seems to move impossibly slow.

Flattery understands teenagers well: their performative aloofness, the way they watch, skulk, and plan their actions in response to others. Mae and Shelley meticulously study the other women in the Factory. They are hyperattuned to their pose, their clothing, and the effect they have on others. They talk frankly about sex. They pretend not to care, when they care oh so very much.

But for people so consumed by the audio recordings, there is little discussion of what is happening beyond the typewriter. Perhaps it feels too impossible, too unreachable, so instead Mae and Shelley obsess over what they hear, and the audio pollutes their thoughts. It is jarring, though, for a novel set in Warhol’s empire to never mention its emperor. His name is only used twice in the novel, and he makes very few appearances, serving more as a spectral force than a concrete presence. It’s an odd choice given that so much of Nothing Special has been taken from life, and that Mae finds a voyeuristic pleasure in listening to the tapes and examining the people around her. Why disguise the principal figure around whom everyone and everything orbits?

Why, for that matter, set another novel in Warhol’s New York? True, Mae, Shelley, and their real-life counterparts were never famous—they were never the “superstars”—and there is something to be said for revealing the labor behind the myth. But there is more than one downtown and more than one story about teenagers, counterculture, and art in New York in the 1960s. And as thoroughly as Flattery may have read Warhol’s writings, it doesn’t mean she understands that New York. Flattery lives in Ireland, which is not to say that she shouldn’t write about Warhol, but rather that her writing, at times, reads like that of an outsider. For one thing, New Yorkers don’t queue, they stand in line. For another, the novel’s version of the Factory, on East 72nd Street, isn’t “somewhere in Midtown.” (One early location for the real Factory actually was in Midtown—on 47th Street.) Where are the teenage slang, the smells, the crowds? Outside of Macy’s, Bloomingdale’s, and a few street names, there’s nothing that makes this feel like New York in 1968, or 2010—or, for that matter, 2023.

It doesn’t help that Mae is disaffected and flat, if at times wryly funny. The voice befits her backwards gaze—when the novel opens, she is middle-aged—but it also reflects trends within the contemporary literary landscape. There is a rhythm to Flattery’s writing that is occasionally fascinating but also anesthetizing. It can also read as if Mae is looking at life through a window, which is what memory is, but not necessarily what novels are. Perhaps it isn’t the thing to say, but I miss big flamboyant sentences and effusive descriptions, worlds that feel as tactile and real as this one I live in. Mae hardly seems three-dimensional, which makes sense because she is at an age when body and self shapeshift almost daily, but New York? The Factory? Warhol? They should be fully drawn and substantive. They should have gravity and force.

In looking backwards, Flattery makes clear that nostalgia is mostly performance. No time is better or more perfect; there is no real halcyon day. While the silvery glitter that seems to bedeck all that is Warhol surely existed, so too did lots of boring downtime, bad conversations, petty feuds. The Factory was both epicenter and quicksand, filled with lost lives, sad stories, and overshadowed women.

¤

Grace Linden is a writer and art historian. She lives in London.

LARB Contributor

Grace Linden is a writer and art historian. She lives in London.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Sophomoric Sophomores: On Elif Batuman’s “Either/Or”

Batuman’s follow-up to her Pulitzer-nominated debut is another breathless exploration of college life.

Joy Is Analog: On Jennifer Egan’s “The Candy House”

In this sequel to “A Visit from the Goon Squad,” joy resides in the dirt and dust of the world.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!